Central African Republic: New Spate Of Senseless Deaths, Says HRW

Five days of sectarian violence that gripped Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic, between September 25 and October 1, 2015, led to at least 31 targeted killings of civilians.

Based on interviews in Bangui, conducted between October 7 and 13 with witnesses, Human Rights Watch found that at least 31 civilians, possibly many more, were shot at point-blank range or stabbed to death, or their throats were slit. The vast majority of killings were by armed members of Muslim self-defense groups, although armed members of the mostly Christian and animist anti-balaka group also incited and participated in the violence, at times fighting with the Muslim groups. Some of the victims were burned in their homes or in places where they sought shelter. The victims included nine women – one of them eight-months pregnant – and four elderly men. Human Rights Watch confirmed eight other cases in which the victims were armed men.

“Civilians in Bangui urgently need protection from the brutal sectarian violence that once again has engulfed their city,” said Lewis Mudge, Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. “The interim government and international peacekeepers should be ready to react quickly to save lives when sectarian violence breaks out.”

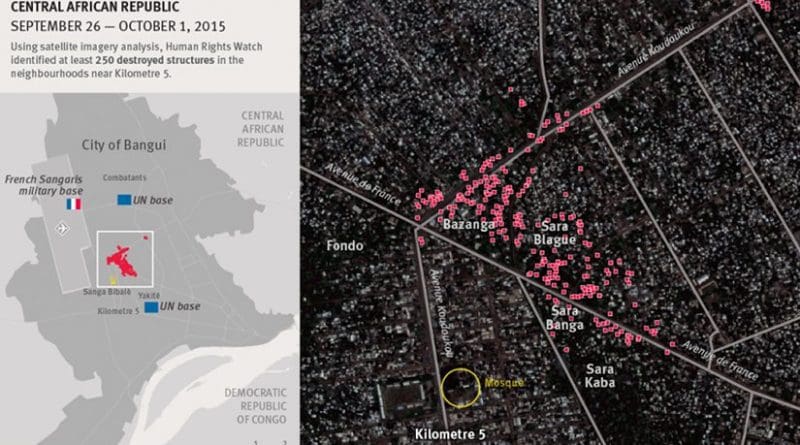

In addition to the killings, armed men from both communities looted and destroyed property. Using satellite imagery analysis, Human Rights Watch identified at least 250 destroyed structures from the neighborhoods near Kilomètre 5, the city’s main Muslim enclave. Two churches and a mosque were also destroyed.

Protecting civilians from further violence of this nature will require rapid responses to requests for help on existing hotlines and more active patrolling by the United Nations peacekeeping mission in flashpoint areas, where communities of different sectarian backgrounds come into contact with one another, Human Rights Watch said. Since the violence ended on October 1, Human Rights Watch has received credible reports of continued isolated killings in the neighborhoods north of Kilomètre 5.

The UN peacekeeping mission, MINUSCA, had approximately 1,120 police and 1,100 soldiers stationed in Bangui at the time, supported by 900 French peacekeepers known as Sangaris. UN officials said the peacekeepers helped to bring 200 aid agency and UN staff to safety and to secure key installations in the city, including the airport and government buildings. The peacekeepers also prevented armed men from other parts of the country from entering the capital. UN officials told Human Rights Watch that their efforts to protect civilians were hampered by barricades set up by anti-balaka, civilians on the barricades, and the general confusion.

Witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they saw no presence of the approximately 900 national gendarmes in Bangui during the violence.

On October 9, the National Transitional Government reported that at least 77 people had died, based on body counts at morgues. Officials could not distinguish who among the dead were armed attackers or civilians caught in the crossfire between the Muslim self-defense groups and the anti-balaka or whether any civilians were deliberately targeted. Another 414 people were injured, the government said.

This latest round of sectarian violence was set off by the death of a 17-year-old Muslim motorcycle taxi driver, Amin Mahamat, whose body was discovered along a main street early in the morning of September 26, with his throat slit. In revenge, Muslim self-defense groups from Kilomètre 5 began to attack Christian and other neighborhoods near the enclave. A UN police unit, part of MINUSCA, based on the outskirts of Kilomètre 5, was unable to stem the violence.

Ali Fadul, the president of the Muslim self-defense groups in Kilomètre 5, told Human Rights Watch, “After the people saw his [Mahamat’s] body they revolted.… There had been too many cases of Muslims being targeted.” Prior to the violence and chaos that have gripped the Central African Republic since March 2013, 122,000 Muslims lived in the capital. Only an estimated 15,000 remain.

Ancien Ngandra, a 66-year-old retired civil servant, was killed in the Sara neighborhood, just north of Kilomètre 5. A witness told Human Rights Watch, “Muslims came into the house and pulled Ancien outside. He tried to say something, but the attackers said, ‘Shut your mouth, don’t speak.’ When they were in front of his house they shot him in the stomach and in the head. He was not anti-balaka or Seleka. He was just an old man.”

In nearby Yakité neighborhood, a 45-year-old woman said she left her house to hide in a neighbor’s house when she heard nearby gunshots and grenade explosions. As she ran, she saw another neighbor, Abel Yakité, and his wife trying to flee. “As they were leaving the house, four young Muslim men with rifles approached them,” she said. “They shot dead both Yakité and his wife when they were on the veranda.”

As the information about the violence spread, armed men from the largely Christian and animist anti-balaka encouraged and committed violence against international peacekeepers. The anti-balaka and their supporters quickly set up barricades across the city, sometimes encouraging women and children to join them, possibly to deter peacekeepers from trying to take down the barricades. In some instances, the anti-balaka fought with the armed Muslims. Some soldiers from the national army, known as the FACA, helped and supported the anti-balaka fighters.

The anti-balaka also encouraged attacks on foreigners whom they blamed for doing nothing to stop the violence. Text messages circulated encouraging people to stone foreigners’ vehicles. Anti-balaka fighters and others seeking to take advantage of the chaos looted nine aid agencies, most of them a few kilometers from the neighborhoods where the violence occurred.

On September 28, approximately 600 prisoners escaped from the capital’s main Ngaragba prison, a severe setback to fighting impunity in the country. Some prison guards and soldiers from the national army facilitated the escape by opening the main gate, possibly because some of the inmates were soldiers. Rwandan UN peacekeepers stationed near the prison tried to deter the escape by firing into the air, and on at least one occasion at the prisoners, injuring one, but they were unsuccessful.

Re-establishing a functioning prison that meets basic prison conditions should be an urgent priority for the UN and interim government authorities, Human Rights Watch said.

The violence in Bangui came ahead of national elections, which were to start with a referendum on October 4, but have since been delayed.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) opened a new investigation in the Central African Republic in September 2014 following a referral from the interim president, Catherine Samba-Panza. On September 30, the ICC prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, warned that those who commit crimes within the court’s jurisdiction “can be held individually accountable.”

“The interim government should ensure that its gendarmes and soldiers help protect all civilians, Christian and Muslim, and don’t contribute to the violence,” Mudge said. “The dreadful cycle of tit-for-tat killings can only be stopped when those responsible are held to account, prison doors are kept closed, and combatants are disarmed.”