After Collapsed US-Russia Agreement, Advantage Assad – Analysis

By IPCS

By Derek Verbakel*

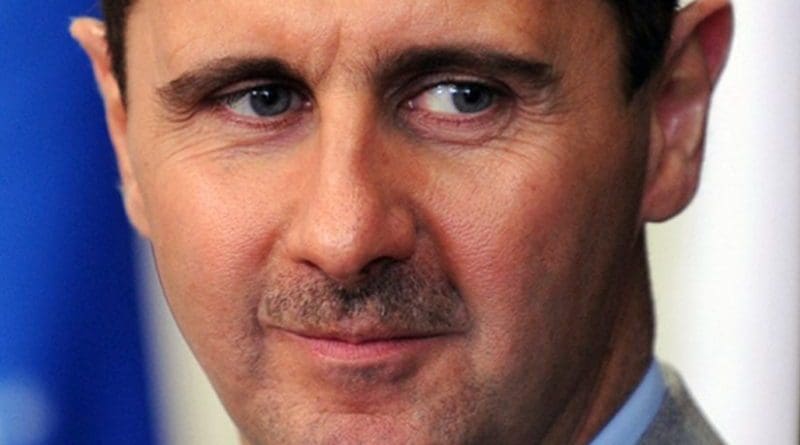

On 19 September, the Russia-backed regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad declared dead the flawed-but-hyped peace deal enacted a week earlier by the US and Russia. The agreement aimed to cease hostilities between warring groups; provide humanitarian aid to Syrians; reinvigorate political talks; and facilitate US-Russia cooperation in targeting Jabhat Fatah al-Sham (JFS, the recently rebranded al Qaeda affiliate in Syria) and the Islamic State (IS). None of this came to fruition. Instead, the unraveled peace agreement has allowed for the acceleration of processes already underway: it has empowered Assad and his backers, weakened the US and the more moderate opposition, and strengthened the jihadis. In this context, diplomatic talks such as those resumed on 15 October are likely not to resolve the conflict and to advantage the Assad regime and Russia.

It was only after Russia’s intervention just over a year ago that Assad’s mounting territorial losses were reversed. Sidelining Iran’s patronage, Russia gained leverage over Assad, whose rule secures Moscow’s perceived existential strategic imperatives in the region; and by extension, globally.

Assad, now determined to regain control of the country by all means necessary, has capitalised on the political process attending the September agreement. The collapsed ceasefire is widely associated with the targeting by Russian airstrikes of a UN aid convoy destined for the rebel held eastern Aleppo city on 19 September. Yet, just two days prior, US bombs ostensibly meant for the IS killed 62 Syrian government soldiers in Deir al-Zour. This gave the regime – which never stopped blocking aid shipments and striking rebel held areas – a pretext to cite the US as well as rebel violations as justification to renounce the ceasefire. Since then, joined by Russian planes and Iranian-backed Shia fighters from several countries, Assad has stepped up vicious assaults on Aleppo neighbourhoods under the control of the JFS and aligned groups.

For the US – which has been unsuccessful in past diplomatic efforts to reach a political solution with Russian cooperation – another failure has further weakened its ability to somehow unseat Assad or reach a favourable future international agreement. The US will not risk escalation by attempting to destroy the Syrian Air Force while Russian personnel are stationed at Syrian air bases; and the establishment of a no-fly zone is impracticable without Russian cooperation.

US Secretary of State John Kerry has claimed his leverage in peace talks was sapped by the Obama administration’s history of lacking credible threats of force in response to repeated regime transgression of ‘red lines’. Banking on a change in Russian goals or sudden goodwill in negotiating to solve the Syria crisis seems to have been imprudent. Russia has boldly asserted the right to do as it pleases in Syria: to abet the regime as it breaks ceasefires in pursuit of military gains.

A lack of faith in the US stemming from the abortive September 2016 ceasefire has also fuelled shifts in the behaviour and balance of power between more extreme and so called “moderate” armed opposition groups. In a steadily crystallising view among “moderates,” the US’ motives in Syria, while always suspect, have become even more so due to Washington’s ongoing failure to effectively pressure Assad to release or even relax his grip on power. The growing perception is that like Russia, with whom the US is increasingly seen as inadvertently collaborating, American intervention too is ultimately enabling Assad. The regime has ramped up its brutality in past weeks, and ever more apparent seems the record of the US’ failure to extend meaningful support to its “moderate” allies. This has validated the narratives of more extreme groups, chiefly the JFS, who have presented themselves as leading the wider “revolutionary” opposition dedicated to ridding Syria of the Assad regime.

This perception has been strengthened by the JFS through incorporating smaller Islamist rebel factions under a hardliner-dominated coalition banner that operates alongside more moderate opposition fighters. This ‘marbling’ of jihadis with other rebels keen for support affords the former a greater shelter from the US-led coalition airstrikes loath to harm “moderate” forces. Yet the relative power of the JFS within the opposition is growing, while that of “moderate” rebels wanes. The IS, which has battled government forces and other rebels, also gains from the US’ reluctance to boost arms shipments to “moderate” factions for fear of weapons falling into the wrong hands. Moscow and Damascus eagerly characterise the opposition monolithically as “terrorists” requiring eradication while freely targeting more “moderate” groups in an attempt to homogenise the opposition. This dwindles elements influenced by American, Turkish, Saudi, and Qatari opponents of Assad while framing his continued campaign as indispensible to the global ‘war on terror’.

In this context, Russia will continue to manipulate diplomatic talks to relieve pressure and provide cover while Assad makes gains on the ground, which they will avoid conceding due to perceived existential imperatives. The 20 October unilateral ceasefire announced by Russia constitutes Russia calling the shots, and any ceasefire met with opposition compliance tilts in favour of Assad, who is able to resupply and fortify his forces. When and in what condition is uncertain, but it appears to be only a matter of time before Assad recaptures Aleppo. The opposition will become increasingly deterritorialised and the conflict will transform and rage on.

As always, sadly, ordinary Syrians bear the burden of political failure.

* Derek Verbakel

Researcher, IReS, IPCS