Intimations Of Mortality: And Why This Is The View From My Bedroom – OpEd

Recently, as I began my 49th year on this earth, I was ambushed by questions of mortality that had not troubled me for nearly 20 years, when both my grandmothers died in swift succession, and I, as a generally chaotic twenty-something, had to grapple with loss, and with questions of old age and memories of childhood that I was not necessarily equipped to deal with.

I realize that it’s arguable that all my work for the last five years, chronicling the lives — and sometimes the deaths — of those subjected to torture and abuse at Guantánamo and elsewhere in America’s “War on Terror” has dealt explicitly with questions of mortality that are far beyond what most people deal with in their daily lives, and that this may well have had an impact on me that I have not been able to gauge myself.

However, in terms of my personal encounters with mortality, the greatest tests since those encounters with the deaths of my grandmothers have come this year, with the death of my father, and with my own intimations of mortality, prompted by my father’s death, the illness of my mother, and by my own unexpected encounters with the fragility of my own life.

I don’t imagine that losing a father can ever be easy. Death can be sudden, as it was in my father’s case, or slow and painful, and I imagine the former is always preferable, unless there are outstanding issues that a sudden death would prevent from being raised, discussed and — hopefully — dealt with, but this was not the case with my father. Although we were not exceptionally close, as he had remarried after the failure of his first marriage to my mother, and this second family had been the focus of his life for 35 years, we had, over time, developed a great liking and respect for one another, as our lives and circumstances changed, that involved some deep and unspoken affection and mutual understanding.

At my father’s funeral, just outside Skipton, North Yorkshire, where he had moved just one day before a heart attack took him away in his sleep, there were numerous condolences cards from the various phases of his life, but most of all, it seemed, from the Norfolk Broads, where he and his second wife Barbara had lived for the previous 12 years, deeply involved in the local church community, where he was widely admired for his kindness and for being “a gentleman,” and thoroughly enjoying what he described as his and Barbara’s “12-year holiday.” Retirement clearly suited him more than work ever had, and he also delighted in becoming a grandparent — first when my son was born, and then when his step-daughter (to whom he had been a father almost all her life) had two boys.

Under these circumstances, it was difficult to see my father’s death as something sad in and of itself, and much easier to note that a sudden death leaves everyone a little confused, and especially leaves a hole in the lives of those closest to the departed — in my father’s case, Barbara, who, half-laughing, half-crying, complained that my father had wanted to be back in the Yorkshire Dales, where he had enjoyed walking as a young man, but that, as soon as they had returned, he had abandoned her.

My father’s death coincided, alarmingly, with serious illness on my mother’s part. Diagnosed and dealt with, this is a panic that has passed, but at its height my mother spoke to me on the phone and then promptly forgot who I was, which was as shocking a conversation as I have ever had in my entire life, as nothing had previously encouraged me to think that, one day, my mother would no longer know who I am.

In the end, these events — my father’s death, and my mother’s temporary amnesia, brought on by an untreated infection — took place in the same week, the first week of February, when I was in Poland, touring a sub-titled version of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo,” which I co-directed with filmmaker Polly Nash, and wondering why I was suffering from deep and disabling pain in my right foot, when there was no discernible reason for it.

The problem with my foot — which, in connection with my father’s death and my mother’s illness, prompted some serious intimations of mortality on my own part — has been a long and slowly unfolding nightmare. The big toe of my right foot first started playing up in the New Year, when I visited New York and Washington D.C. for the ninth anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo. At the time I thought I’d hit it on something and bruised it, but this obviously wasn’t the case when it didn’t get any better.

At the end of January, I finally sought advice from one of the doctors in the group surgery nearest to my home in London. Thinking it was some sort of infection, he put me on a week-long course of antibiotics, which didn’t work, but this wasn’t decisively confirmed until I was in Poland, where I put up with the pain until I returned to the UK. Even then, the doctors continued to be confused, and the hope appeared to be that whatever it was might pass of its own accord.

It wasn’t until a second toe — the middle toe on my right foot — swelled up at the start of March that this approach to the problem was finally ditched, and I was referred to the Accident & Emergency Department at Lewisham Hospital, with instructions to insist on seeing the vascular team, who deal with problems relating to blood flow.

The vascular team reassured me that the problem posed by my increasingly painful and now blackening toes was not fatal, and would not, in all likelihood, lead to amputation — both of which were a relief, given how severe the problem now appeared to be, with my middle toe acutely sensitive to the slightest touch — but the doctors then proceeded to give me an appointment for an arterial scan 13 days later. With hindsight, I realize that I should have complained that 13 days was far too long to wait when I was already in great pain, but for some reason this didn’t occur to me, and I spent the next two weeks never getting more than ten minutes sleep at a time, which I don’t recommend to anyone who wishes to preserve their sanity.

Although I had been prescribed codeine, it wasn’t enough to block the pain and every time I laid down to try to sleep, pain would shoot through my foot as soon as it had been lying motionless for a few minutes. This went on and on, over and over every night, from before midnight to long after dawn, with sleep almost entirely unattainable — as much of a mirage as it was for the poor prisoners in Guantánamo who were subjected to what was described, euphemistically, as the “frequent flier program,” in which, every two hours, over the course of days, weeks or even months, prisoners were moved from cell to cell so that they were deprived of meaningful sleep for signficiant periods of time, and gradually — or, in some cases. precipitously — suffered severe mental disintegration.

Under these circumstances, my ability to think clearly and to write — the incessant driver of my life for the last five years — finally started to desert me, and on Friday last week (the day after I finally received an arterial scan), the consultant at Lewisham found me a bed on a ward with a great view over Ladywell Fields, the landscaped park that flanks the Ravensbourne river as it makes it way down to Deptford to meet tthe great body of the Thames.

Away from my computer, I had the opportunity to reflect on how well the NHS is operating, as the axe wielded by the coalition government hangs over it, and how the last thing it needs is the kind of unprecedented top-down reorganization proposed by health minister Andrew Lansley, whereby consortia of GPs — assisted by the Tories’ private sector chums, of courtse — will be responsible for managing the hospitals’ £80 bn budget, distributing contracts on a competitive basis that is intended to break up and effectively privatize the NHS.

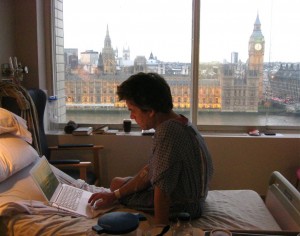

After two days, I was referrred on to St. Thomas’s Hospital on the Thames, directly opposite the Houses of Parliament, where, after an ambulance journey with two dedicated public servants, who were proud of their jobs and fearful of the government’s intentions, I was greeted warmly and processed efficiently in a buzzing A&E department, and then taken up to a room in a ward on the 10th floor with the most amazing view of the Houses of Parliament — hence the photos, and my mention of the view from my bedroom in the title of this article — while doctors and consultants began working out how to redirect the flow of blood to my starved and damaged toes, which, it has become apparent, was blocked because of minor arterial damage elsewhere in my body.

However, although I’m now being thoroughly monitored by professionals — and being given painkillers by professionals — the pain has still not gone away, an unbroken night’s sleep is still an inaccessible memory, and I’m waiting to see if body scans, a course of blood-thinning drugs and another course of artery-expanding infusions will actually bring life back to my toes and sleep back to my life.

With a new-found respect for life — through the sudden loss of my father, the temporary amnesia of my mother and my own intimations of mortality — I have finally put aside the last vestige of my self image as some sort of youthful revolutionary, a mirage which many people my age will recognize, but which in my case proved surprisingly resistant to common sense — at least as far as smoking was concerned, which I continued to enjoy and to endorse enthusiastically up until last Friday, even though it undoubtedly contributed to my current problems. I gave up drinking alcohol three years ago, which was easy, but continues to impress many people I meet, who struggle with their own intake, but on smoking I was way behind the pack, often the only addict sneaking out the back to sustain a habit that was increasingly shorn of all its false glamour.

The most demonstrable example of my belated maturity took place at noon on Friday March 18, when, after 29 years of life as an enthusiastic chain smoker, I smoked my last ever cigarette outside Lewisham Hospital.

Having seen the future, and recognized my own death, I’d now like to get on with my life again. Please bear with me as I recover from my current suffering, and get back to work. I can’t promise that I’ll be writing at quite the same hectic pace I’ve maintained for the last four years as a nicotine- and caffeine-fuelled freelance journalist, but I haven’t yet abandoned my beloved coffee, and, given that my indignation at the world’s many injustices is undiminished, I expect that I’ll be as opinionated as ever, if not quite as relentlessly workaholic.