The Case For Tactical Nuclear Weapons – Analysis

Are tactical nuclear weapons outdated relics of the Cold War? Should they be phased out of the US’ and NATO’s arsenals? On the contrary, says John Klein. As he sees it, the deterrence value of these weapons remains as powerful as ever.

By John J. Klein

Nuclear weapons and deterrence continue to be topics of heated discussion among arms control advocates and policy makers within the United States and abroad, as exemplified by the ongoing diplomatic dialogue to limit Iran’s nuclear capability. Within the arms control community, some view nuclear deterrence as being an antiquated remnant of the Cold War, with no utility in today’s more multilateral security environment. Still others see tactical nuclear weapons as being especially counterproductive to peace and stability, and argue that they should be phased out of U.S. and NATO military strategies. Yet this view is incorrect. Because tactical nuclear weapons are at times a more credible response under the principles defined by customary international law, these weapons enhance deterrence and subsequently improve international peace and security.

Background

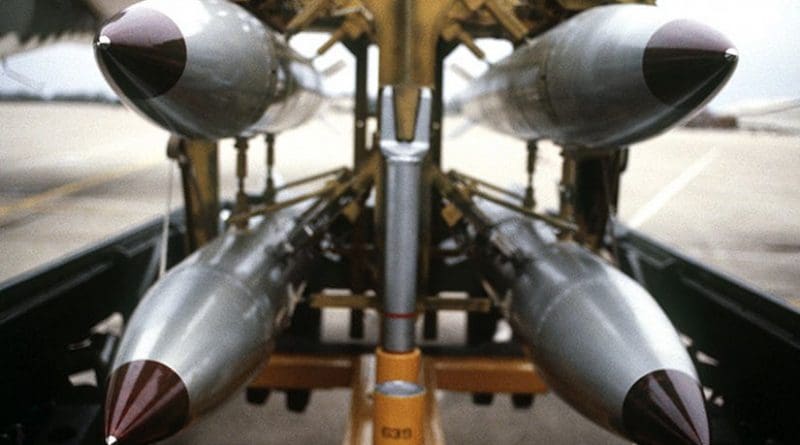

Tactical nuclear weapons are frequently defined as non-strategic nuclear weapons, or nuclear warheads not currently covered under the 2010New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty. In particular, the U.S. B-61-aircraft-released gravity bomb is categorized as a tactical nuclear weapon, and this weapon is currently an integral part of U.S. and NATO military plans. U.S. tactical nuclear weapons typically have lower detonation yields—reportedly ranging from 0.3-300 kilotons—compared to strategic warheads on intercontinental ballistic missiles or submarine-launched ballistic missiles, which reportedly have yields upwards of 1.2 megatons. While the United States forward deploys tactical nuclear weapons in Europe as part of a sharing agreement with NATO, their numbers have been reduced from a peak of 8,000 to about200 today. In contrast, Russia is estimated to have upwards of 6000 tactical nuclear weapons in its arsenal.

The most current U.S. Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) provides guidance related to both nuclear strategy and tactical nuclear weapons. Released in 2010, the NPR reaffirms existing strategic guidance that the primary role of the U.S. nuclear arsenal is to deter a nuclear attack on the United States, its allies, and partners. Accordingly, the United States will maintain the capability to forward-deploy U.S. nuclear weapons on tactical fighter-bombers and heavy bombers and will proceed with a full scope life extension program for the B-61 bomb. The United States will also continue and, where appropriate, expand consultations with allies and partners to address how to ensure the credibility and effectiveness of the U.S. extended deterrent.

What the critics say

Despite their current role in support of extended deterrence to allies and partners, critics of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons argue for their reduction or elimination. In May 2012, the arms control group Global Zero called for eliminating all U.S. tactical nuclear weapons over the next ten years, stating that their strategic utility is practically nil. Global Zero believes that the extended deterrence commitment to partners or allies could be met by either U.S. strategic nuclear and conventional forces, instead of tactical nuclear weapons. Additionally, a 2013 report by the Stimson Center states that having tactical nuclear weapons will likely increase the proliferation of the weapons by other counties. The report concludes that tactical nuclear weapons add little to deterrence, complicate safety and security, and invite military preemption. Still other arms control advocates see tactical nuclear weapons as leading to conflict escalation through the eventual use of larger, strategic nuclear weapons. Hence, tactical nuclear weapons are said to never be a suitable response and should not be part of any deterrence strategy.

Despite the criticisms, tactical nuclear weapons still play a role in the U.S. extended deterrence promise to partners and allies, and this promise helps limit the proliferation of nuclear weapons in other countries around the globe. Without extended deterrence, U.S. partners or allies might feel compelled to develop their own nuclear weapons, in order to guarantee their security against future nuclear power aggressors. Moreover, tactical nuclear weapons actually enhance extended deterrence, when considered within the international norms of armed conflict.

The law of armed conflict

Deterrence works only if a credible threat of retaliatory force exists, and for the U.S. defense community, credibility is typically governed by what is known as the Law of Armed Conflict (LOAC), which is an extension of that part of customary international law regulating the conduct of armed hostilities. When considering the utility of tactical nuclear weapons, two LOAC principles are most germane: the principles of military necessity and lawful targeting. The principle of military necessity calls for using only that degree and kind of force required for the partial or complete submission of the enemy, while taking into consideration the minimum expenditure of time, life, and physical resources. This principle is designed to limit the application of force to that required for carrying out lawful military purposes. Although the principle of military necessity recognizes that some collateral damage and incidental injury to civilians may occur when a legitimate military target is attacked, it does not excuse the wanton destruction of lives and property disproportionate to the military advantage to be gained. For the employment of nuclear weapons, therefore, the weapons used should not cause more destruction than necessary to achieve military objectives. Consequently, a smaller yield nuclear weapon may be preferred over a larger yield warhead, if the military objectives can still be achieved.

In contrast, the principle of lawful targeting requires that all reasonable precautions be taken to ensure the targeting of only military objectives, so that damage to civilian objects (collateral damage) or death and injury to civilians (incidental injury) is avoided as much as possible. When considering the size of nuclear yields under this principle, an excessively large nuclear warhead could be more difficult to successfully employ against a more localized target, with non-combatants located nearby.

Implications

In order to have a credible nuclear deterrent—one that is able to deter potential future threats—the United States must have a variety of nuclear weapons that are able to deliver from minor to severe military effects. The U.S. nuclear arsenal, therefore, should include an ample number of low-yield nuclear weapons, so that the president is provided with the best choice of potential response options following an adversary’s attack. The application of the principle of military necessity to any potential U.S. nuclear response following an act of aggression means that the response should not exceed the kind or degree of force needed to accomplish the military objective. Additionally, the application of the principle of lawful targeting means that a nuclear response should discriminate between military objectives and civilian objects to mitigate collateral damage and incidental injury. For these reasons, low-yield tactical nuclear weapons may prove to be the preferred nuclear response option vice larger and potentially more indiscriminate nuclear warheads.

If an adversary used a low-yield nuclear weapon against a NATO member and a commensurate low-yield nuclear weapon was not readily available for a response to the attack, NATO leadership would need to weigh other options, such as employing a higher-yield nuclear weapon or conventional weapons with a similar destructive effect. Both options pose challenges for policymakers. Using a significantly higher-yield, strategic nuclear weapon might greatly increase the possibility of conflict escalation, which is seldom a preferred outcome. The employment of a higher-yield nuclear response option might also exceed the degree of force needed to accomplish the military objective and, therefore, could violate the principle of military necessity under the LOAC. Additionally, because these strategic weapons are carried aboard ballistic missiles, employment of strategic nuclear weapons proves more problematic because of their potential overflight of other countries, which can miscommunicate the missile’s intent and target. As for planning for and relying on a conventional response to a nuclear strike, U.S. policymakers would be required to consider how this might undermine allied perceptions of Washington’s resolve, commitment to the idea of extended deterrence, and the credibility of the American nuclear arsenal.

Final thoughts

Nuclear weapons and deterrence are important topics that deserve to be debated among the international community. Such debate is especially meaningful because of the nuclear ambitions of Iran andNorth Korea, along with ongoing pressure to modernize the U.S. nuclear forces. Any reduction in the number of tactical nuclear weapons in either U.S. or NATO shared stockpiles, however, should be made with serious consideration of the risks posed by such an action. Tactical nuclear weapons—under some scenarios—provide a more credible threat of retaliatory force to a potential nuclear attack when compared to strategic nuclear weapons. As a result, these weapons improve the viability of extended deterrence and therefore help limit the proliferation of nuclear programs. Also, low-yield tactical nuclear weapons can help limit conflict escalation and avoid unnecessary civilian casualties. For all these reasons, tactical nuclear weapons still have a critical role to play in U.S. and NATO security measures.

John J. Klein is a Principal Analyst at Analytic Services in Falls Church, Virginia and writes frequently on national security, military strategy, and the Law of Armed Conflict. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Analytic Services or those of the United States Government.