Japan Seeks Stronger Strategic Ties In Southeast Asia – Analysis

By ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute

By Malcolm Cook, Leo Suryadinata, Mustafa Izzuddin and Le Hong Hiep*

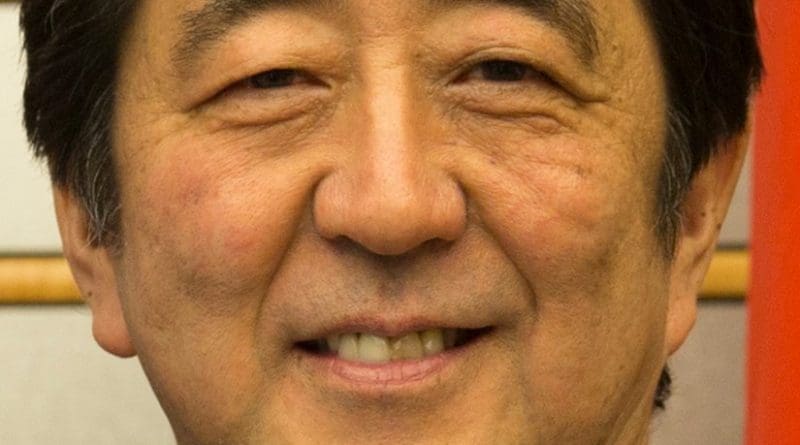

Over six days in January 2017, Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe travelled over 18,000 kilometres visiting the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam and Australia – Southeast Asia’s three most populous countries and Japan’s most important security partner after the United States. The timing and itinerary of the whirlwind tour reflect many shared anxieties about the Donald Trump presidency; Japan’s mounting concern over China’s challenge to its leading economic position in Southeast Asia; and Abe’s efforts to leverage on these concerns to enhance Japan’s regional leadership.1

For the last two decades, Japan’s grand strategy has centred on supporting the Asia-Pacific security order led by a United States in relative decline and at war in the Middle East, and countering an emboldened Beijing’s efforts to replace this with an Asian security order led by China. The Trump presidency throws into greater question US commitment to maintaining its leading strategic position in the Asia-Pacific and the means by which it may seek to do this. Southeast Asian countries, particularly Indonesia under President Jokowi and the Philippines under President Rodrigo Duterte, have become major beneficiaries of Beijing’s infrastructure diplomacy, raising the potential for China to replace Japan as their major infrastructure and development partner.

This joint perspective will look at what Abe’s visit to each of the countries tells us about their interest in enhancing relations with Japan. It is kept in mind that a commonality of interests between states is distinct from a convergence of interests, even if both do support closer cooperation.

JANUARY 12-13: THE PHILIPPINES

By Malcolm Cook

The Philippines stop was the first. Philippine foreign and security policy under Duterte has been aggravating Japanese concerns about Southeast Asian support for the current US-led security order and of China displacing Japan economically in the region. From 2013 to 2016, President Aquino and Prime Minister Abe went about successfully forging a close personal relationship, and the Aquino administration’s grand strategy underpinned a strong commonality of interests with Japan. The sharp changes to Philippine foreign and security rhetoric and policy that have come with Duterte raise questions about the future relationship between the US’ major ally in Northeast Asia and in Southeast Asia.

Yet, as with Duterte’s visit to Japan in October 2016, Japan-Philippine relations were enhanced due to the common and converging interests of both parties. Duterte, citing the Bible, referred to Japan as “a friend that is closer than a brother”2 and invited Abe, the first foreign leader to visit the Philippines since Duterte came to power in June 2016, to breakfast at the Duterte residence in Davao City.

On the economic front, Prime Minister Abe, who brought a heavy-hitting business delegation with him, announced a five-year 1 trillion yen ($8.8 billion) aid and investment package focussed on the Duterte administration’s ambitious infrastructure programme. This is one of the largest aid packages ever assembled by Japan for a single country and at least matches in dollar terms the infrastructure commitments made by China during Duterte’s visit to China in October 2016. This new Japanese package in combination with the Japanese commitments made in October 2016, and to the Aquino administration should maintain Japan’s position as the Philippines’ most important infrastructure and development partner, or at least until China decides to up the ante again in the ongoing infrastructure battle between the two Northeast Asian neighbours. Duterte has already announced plans to attend the One Belt One Road summit in China in May.3

On the security front, the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs briefed journalists that the two leaders agreed about the necessity and benefit of continued US commitment to the region and that territorial and maritime rights disputes should be resolved through the rule of law.4 On the Japanese side, Abe can play a reassuring bridging and replacement role between the United States and Duterte. In turn, Duterte can reassure Japan and the broader region that Philippine foreign and security policy has not swung away from supporting the current regional order and toward China as much as many fear.

Backing this up, during the visit it was announced that Japan will participate in the annual US-Philippine Balikatan exercise, reaffirming that the largest and most important US- Philippine military exercise will not be cancelled this year but rather expanded to include the Philippines’ second most important security partner.5 Three days after the Abe visit, the Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs announced that it had filed a diplomatic protest with China over the militarization of China’s recently constructed artificial islands within the Philippine exclusive economic zone.6

JANUARY 13-15: AUSTRALIA

By Malcolm Cook

Australia was the only leg of the Abe regional tour beyond Southeast Asia. The inclusion of Australia reflected the importance of Japan and Australia’s shared Southeast Asian concerns, and of the sustained and broad deepening of Australia-Japan security relations that had taken place over the last two decades. Japan and Australia are frequently referred to as the “northern” and “southern” anchors of the US alliance system in East Asia, and more broadly the US-led regional security order. Southeast Asia accounts for much of what lies between these anchors.

Abe’s visit down under had four important takeaways for Southeast Asia:

- Both prime ministers reaffirmed their country’s continued strong support for the US- led regional security order and the US role in East Asia. Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull stated that “for both of our nations, the United States remains the cornerstone of our strategic and security arrangements. Our respective Alliance, Alliance of the United States are as relevant and important today as they have ever been. We will work closely with the incoming Administration as we have been to advance the region’s interests, and our shared goals.”7

- Their joint statement restated that the TPP is an “indispensable priority because of the significant economic and strategic benefits it offers’’, with both leaders committing to cooperating together to push for the early enactment of the agreement.8

- The two leaders focussed on the South China Sea and North Korea as their two pressing security concerns. Both reaffirmed that the disputes should be dealt with in accordance with international law including UNCLOS. The new Trump administration could well pressure Australia and Japan to become more actively involved in pushing back against China in the South China Sea.9

- Canberra and Tokyo enhanced the ability of their militaries to work more closely with each other. The two leaders signed a revised logistics agreement that permits Japan to provide ammunition to Australia during exercises and operations involving the two militaries.10 The previous agreement was limited to the transfer of equipment related to humanitarian and disaster relief operations. They also committed to the early conclusion of a legal agreement to facilitate future bilateral military visits and exercises.

Abe and Turnbull reaffirmed in word and action their common interest in supporting the US-led regional security order and US presence in the region. This aimed at reasserting certainty in a period of unquestioned uncertainty.

JANUARY 15-16: INDONESIA

By Leo Suryadinata and Mustafa Izzuddin

At first glance, Shinzo Abe’s visit to Indonesia had a clear economic purpose as he brought with him a delegation of 30 prominent businessmen. Japan is a leading foreign investor in Indonesia, with investments reaching US$4.5 billion in the first nine months of 2016.11 Bilateral trade increased to reach US$24 billion in the first ten months of 2016.12 According to Coordinating Maritime Affairs Minister Luhut Pandjaitan, who held Japan up as an “ideal model for infrastructural development”13, Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo and Prime Minister Abe were to discuss four major strategic projects, namely the Patimban port, the Jakarta-Surabaya rail project, the East Natuna oil and gas block, and chemical and fertilizer projects.14

On closer inspection, however, Abe’s Indonesia visit was more strategic than economic. He was mainly concerned with security matters, in contrast to Jokowi who was primarily concerned with economic benefits. With the exception of the Parimban port project, remarks made at the joint press conference after the closed-door meeting were rather anodyne, with both leaders merely stressing continued bilateral economic cooperation.

But what was telling from the press conference was Abe saying that Japan attaches huge importance to maintaining a rules-based order in the South China Sea by resolving disputes peacefully in accordance with international law.15 In this regard, he pledged for Japan to cooperate with Indonesia on maritime security, not least vis-à-vis the Natunas. In reality, however, this is likely to be rejected altogether as Jokowi would be reluctant to draw a foreign country into patrolling Indonesian waters.

Cooperating with Japan on maritime security in the South China Sea could also generate consternation in Beijing, something that Indonesia prefers to avoid, given the enhanced bilateral economic engagement in Sino-Indonesian relations. Perhaps a less controversial development would be for Japan to enhance its maritime cooperation with member countries of the Indian Ocean Rim Association, currently chaired by Indonesia.16

No mention was made of Abe’s “Indo-Pacific Strategy” at the press conference, although the proposal was reported to have been discussed in the closed-door meeting. The proposal seeks to promote “cooperation among Japan, ASEAN countries, the US, Australia and India.”17 This proposal was described by The Jakarta Post as the “Japanese vision of OBOR.”18

The Indonesian media appeared lacking in enthusiasm over Abe’s visit, perhaps because most projects involving Japan were pledges more than concrete undertakings. The Jakarta Post’s editorial expressed disappointment with Abe’s visit and called on Japan to open up its markets to Indonesian agricultural and fishery products, and to “cheap but quality workers”. The editorial also attributed the sluggishness in Japan’s relations with Indonesia to Jakarta “tilting towards China”.19

At the same time, the editorial stated the following: “With Indonesia to a certain extent showing hostility to rising China, Japan is among the few countries that can play a deterrent role vis-à-vis the world’s second-largest economy.”20 Japan can thus help Indonesia limit its reliance on China. Engagement with Japan would also be more acceptable to the Indonesian public.

JANUARY 16-17: VIETNAM

By Le Hong Hiep

Vietnam was the last stop on Shinzo Abe’s tour, but Hanoi is in no way less important than other Southeast Asian countries to his regional strategy. Indeed, four years ago, after returning to the Prime Minister position, Vietnam was the first foreign country Abe visited. Under his stewardship, bilateral relations have been continuously strengthened, driven by strong mutual trust and increasingly convergent national interests in terms of economics and strategy.

Unlike most of the major relationships of both these countries, bilateral ties between the two have generally been problem-free and carry no historical baggage.21 By 2016, Japan had become the largest source of Official Development Assistance (ODA), the second largest foreign investor, the third largest source of tourist arrivals, and the fourth largest trade partner of Vietnam.22 As both countries are members of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), bilateral economic ties will be further strengthened should the agreement survive the current anti-globalization backlash in the United States. Both leaders have publicly reaffirmed their commitment to the TPP with Prime Minister Phuc assuring Abe that Vietnam is taking steps to ratify the TPP.23

During his visit, Abe pledged to provide Vietnam with 123 billion yen (US$1.05 billion) in ODA in the fiscal year 2016, which will be used, among other things, for beefing up Vietnam’s maritime security, improving the country’s responses to climate change, and upgrading the sewage systems of a number of Vietnamese cities. The two sides also signed several loan agreements under which Japan will provide funding for a Vietnamese power plant and the Economic Management and Competitiveness Credit (EMCC) programme that aims to improve Vietnam’s business environment.

While economic cooperation featured high in the agenda of Abe’s visit, the most meaningful contribution of the visit to the development of bilateral ties is perhaps the deepening strategic dimension that it represents.

Specifically, during the visit, Prime Minister Abe announced that Japan would provide Vietnam with six more patrol boats worth US$338 million in addition to the other six that Tokyo pledged to Hanoi in 2014. Japan is reportedly going to sell two advanced radar-based satellites to Vietnam, which are to be delivered in 2017 and 2018 through Japanese ODA.24 Meanwhile, Hanoi is also said to be considering the purchase of second-hand P-3C surveillance anti-submarine aircraft from Tokyo.25

The bilateral focus on maritime security underlines the two countries’ shared concerns about recent shifts in the regional maritime landscape, especially China’s increasingly dominant naval power and its growing assertiveness in maritime disputes. As Japan and Vietnam face Chinese pressures in the East and South China Sea, respectively, strategic cooperation to deal with Beijing has naturally become an urgent need for both sides, and it is this maritime strategic imperative that has sailed their defence cooperation forward in recent years.

At a press conference during the visit, Abe stressed the two countries’ common maritime interests by referring rhetorically to the water of the Red River in northern Vietnam flowing into the South China Sea and the East China Sea which connects with the Tokyo Bay. “Nothing can obstruct the free passage along this route. Japan and Vietnam are two neighbours connected by the free ocean,” he said. He added that the four countries that he visited during the trip were important neighbours of Japan who together share the free Pacific Ocean and fundamental values, and that “the principles of maritime security and safety, and freedom of navigation are very important and the law must be fully obeyed”.26 Although no specific country was mentioned, China’s recent maritime assertiveness seems to be the main background of Abe’s remarks.

In sum, Prime Minister Abe’s visit to Hanoi has further strengthened the comprehensive and virtually problem-free relationship between the two countries, which has been built on strong mutual trust and increasingly convergent strategic interests. As such, Vietnam continues to be a key partner in Japan’s security strategy that seeks to “normalize” and strengthen Tokyo’s international security role against the backdrop of a rising China that has already generated seismic shifts in the regional strategic landscape.

JAPAN’S WEIGHT ON THE BALANCE

Southeast Asian states, to maximize their own strategic autonomy, have long sought to balance their relations with major powers and to make sure that no major power is dominant in the region. Japan under Abe is proactively seeking to strengthen economic and security relations in the region in order to counteract rising Chinese influence and the fear of declining US influence.

Abe’s recent trip reaffirms a commonality of interests on this front between Japan and Australia, and converging interests between Japan and the Philippines and Vietnam. Messages out of Indonesia, as is often the case, are more mixed.

Prime Minister Abe’s strong and recently reinforced political position domestically27 and Japan’s rising strategic anxiety suggest more such trips to Southeast Asia are likely. How receptive Southeast Asian states and ASEAN are to Japan’s proactive diplomacy will inform us how these states are faring in balancing their relations with major powers under current circumstances or if these circumstances preclude such a balance.

*About the authors:

Leo Suryadinata is Visiting Senior Fellow, Malcolm Cook Senior Fellow and Le Hong Hiep and Mustafa Izzuddin Fellows at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.

Source:

This article was published by ISEAS as ISEAS Perspective: Issue 2017 No. 5 (PDF)

Notes:

1 Lisa Murray, “Japan’s Shinzo Abe to visit Australia and cement regional ties amid Trump fears,” Australian Financial Review, 12 January 2017, http://www.afr.com/news/policy/foreign- affairs/japans-shinzo-abe-to-visit-australia-and-cement-regional-ties-amid-trump-fears-20170112- gtq62t

2 President Duterte also used this depiction of Japan during his October 2016 state visit to Japan, “Closer than a brother”, Philippine Daily Inquirer, 28 October 2016, http://opinion.inquirer.net/98773/closer-than-a-brother

3 Paterno Esmaquel II, “Duterte to visit China again in May – report,” Rappler, 20 January 2017, http://www.rappler.com/nation/158889-duterte-visit-china-may

4 “Abe, Duterte agree US has role in regional peace,” Bangkok Post, 13 January 2017, http://www.bangkokpost.com/news/world/1179661/abe-duterte-agree-on-us-role

5 Leila B. Salaverria, “Japan to join PH-US military exercises,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 14 January 2017, https://globalnation.inquirer.net/151630/japan-join-ph-us-military-exercises

6 Patricia Lourdes Viray, “Yasay: Note verbale sent to China after intel verification,” Philippine Star, 16 January 2016, http://www.philstar.com/headlines/2017/01/17/1663541/yasay-note- verbale-sent-china-after-intel-verification

7 https://www.pm.gov.au/media/2017-01-14/joint-press-statement-his-excellency-mr-shinzo-abe- prime-minister-japan

8 Sid Maher, “Turnbull and Abe agree to deepen defence ties and push for Trans-Pacific Partnership”, The Australian, 14 January 2017, http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/nation/turnbull-and-abe-agree-to-deepen-defence-ties-and- push-for-transpacific-partnership/news-story/85c14fdbc3611bd7807c89a0353f561d

9 Henry Belot, “South China Sea: Paul Keating says Rex Tillerson threatening to involve Australia in war”, ABC News, 13 Janaury 2017, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-01-13/paul-keating- accuses-us-of-threatening-australia-with-war/8181160

10 Japan is planning to sign a similar agreement with the United Kingdom, Ryo Aibari, “SDF to supply ammo to Britain: 1st pact with European power”, The Asahi Shimbun, 19 January 2017, http://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/AJ201701190043.html

11 “Indonesia, Japan pledge to step up cooperation”, Xinhua, 15 January 2017, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-01/15/c_135984348.htm

12 Saifulbahri Ismail, “ Indonesia, Japan, discuss high-speed rail project”, Channel NewsAsia, 16 January 2017, http://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/business/indonesia-japan-discuss-high- speed-rail-project/3440758.html

13 Viriya P. Singgih, “Indonesia sees Japan as model for infrastructure development”, The Jakarta Post, 15 January 2017, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2017/01/15/indonesia-sees-japan-as- model-for-infrastructure-development.html

14 Anton Hermansyah and Farida Susanty, “Indonesia to discuss four strategic projects with Japanese PM”, The Jakarta Post, 12 January 2017, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2017/01/12/indonesia-to-discuss-four-strategic-projects- with-japanese-pm.html

15 “Abe pledges fresh security-related aid to Vietnam”, The Japan Times, 16 January 2017, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2017/01/16/national/politics-diplomacy/abe-jokowi-unite- south-china-sea-disputes-plan-two-plus-two-meeting/

16 http://www.kemenkeu.go.id/en/Berita/indonesia-japan-strengthen-cooperation-various-fields 17 Tama Salim and Fedina Sundaryani, “Abe offers RI Indo-Pacific Strategy”, The Jakarta Post, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2017/01/16/abe-offers-ri-indo-pacific-strategy.html

18 Ibid.

19 “PM Abe’s visit”, The Jakarta Post, 17 January 2017, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2017/01/17/pm-abe-s-visit.html 20 Ibid.

21 This is despite the fact that up to 2 million Vietnamese died of starvation in 1945 due to the Japanese occupation. Japan established relations with Vietnam in 1973, but bilateral ties only flourished after Vietnam opened up the economy and embarked on the “diversification and multilateralization” of its foreign relations in the late 1980s. Since then, economic interests have been a key driver of bilateral ties.

22 “Việt Nam muốn Nhật Bản trở thành nhà đầu tư lớn nhất” [Vietnam wants Japan to become its largest foreign investor], Phap luat Viet Nam, 18 January 2017, http://baophapluat.vn/thoi-su/viet- nam-muon-nhat-ban-tro-thanh-nha-dau-tu-lon-nhat-315939.html

23 Yuta Uebayashi, “Japan, Vietnam to cooperate on TPP,” Nikkei Asian Review, 17 January 2017, http://asia.nikkei.com/Politics-Economy/International-Relations/Japan-Vietnam-to-cooperate-on- TPP

24 “Japan gets first int’l customer for advanced Earth observation satellite”, Mainichi, 17 September 2016 http://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20160917/p2a/00m/0na/016000c

25 “Vietnam looks to Japan for anti-submarine aircraft”, VnExpress, 28 June 2016, http://e.vnexpress.net/news/news/vietnam-looks-to-japan-for-anti-submarine-aircraft- 3427050.html

26 “Japanese PM calls for respect for rule of law to safeguard freedom of navigation”, Vietnam Breaking News, 17 January 2017, https://www.vietnambreakingnews.com/2017/01/japanese-pm- calls-for-respect-for-rule-of-law-to-safeguard-freedom-of-navigation/

27 “PM Abe’s dominance in LDP highlighted by speedy move to extend term limit”, Mainichi Shimbun, 27 October 2016, http://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20161027/p2a/00m/0na/005000c