Exodus Of Northeasterners: Reversal Of Globalisation? – Analysis

Way back in December 2001, Naga insurgent outfit NSCN-IM organised an event in Nagaland capital Kohima. One of the many programmes included in the day-long affair, ostensibly to unify the warring Naga factions, was to burn the ‘Indian’ currency notes. As a currency note was thrown into the makeshift pyre, in the presence of some state ministers and security force personnel, one of the insurgent leaders screamed, this note is “a demon which had destroyed the present generation of Nagas”. The underlying frustration of the leader behind the act was evident. Economic opportunities provided by mainland India had taken a toll on the secessionist objective of the outfit. Youths no longer were willing to carry the flag of separatism on their shoulders and were more inclined to benefit from the trends of globalisation, even if that involved travelling to the ‘Indian’ cities.

Indeed, over the years, the migration of thousands of young men and women from the Northeast to various mainland cities in search of educational and career opportunities had eroded the psychological barrier between the two parts of the country and had allayed the prevalent feeling of alienation to a large extent. The ‘feeling of separateness’ remained, but the opinion that ‘India is a foreign country that must be shunned’ had disappeared. Protests against each incident of rape, molestation of Northeastern girls in cities like Delhi and Mumbai was interspersed with the demand for better security. Northeast was willing to assert its Indian identity and was keen to position itself to demand what is rightfully its. Similarly, the young men and women who returned to pursue their careers in their home states after completing their education in the universities in mainland India also remained firm links between the two parts of the country.

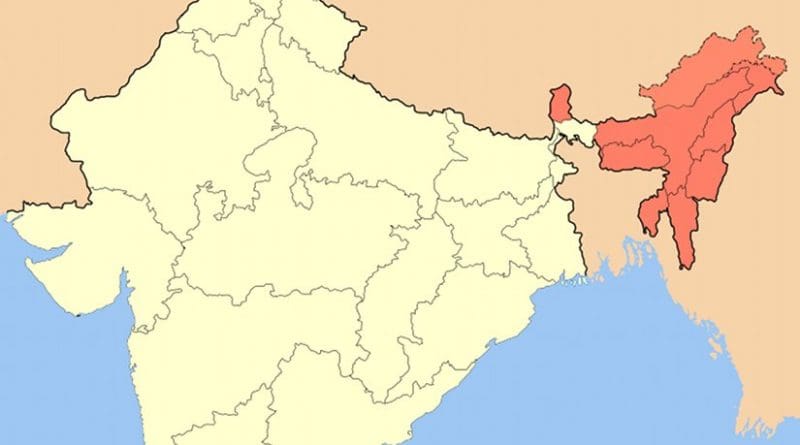

In this context, the reverse forced migration of August 2012 of thousands of Northeastern workers from cities like Mumbai, Bangalore, Hyderabad and Pune to the perceived safety of their own states, exaggeratedly compared with the population movement during the partition by one of the New Delhi-based magazines, was a disturbing disruption to the trend of the last two decades. Truly, India’s nation-building project in the Northeast suffered a big blow the moment the first special train carrying the fleeing passengers crossed over the Siliguri corridor.

Since 1991, Dr Manmohan Singh has been representing Assam in the Rajya Sabha — as a finance minister and then as the Prime Minister. However, even Dr Singh would agree that more than his image of an MP from one of the Northeastern states, it is the process of globalisation that has unified the region with mainland India. Northeast remains a crucial plank for India’s Look East policy and also a territory which shapes India’s China policy. It is an integral part of the country, in the full sense of the term.

With this backdrop, it was amazing to note the way several states have systematically failed to provide a sense of security to the people from the Northeast time and again. What is even more reprehensible in the present context is that the violence and subsequent exodus of people from the Northeast, linked to the July-August violence in the Bodo areas in Assam, was entirely preventable. It required simple alertness and firm police action. What was on display, however, was the same lethargy and political indecisiveness that led to the death of 78 people of Assam. Had a similar zeal with which the law enforcement agencies clamped down on the subsequent protests against the treatment meted out to be Northeastern youths been shown when zealots of Raza Academy and Madina Tul Ilm Foundation carried out the protests in Mumbai’s Azad Maidan on August 11, not a single soul would have boarded the panic trains to Guwahati.

Do these incidents provide any early signs of calamity? Do they mark a return to the age of ethnic exclusivity based on the ‘intolerance of the other’? It needs to be noted that the Northeast, similar to any other part of the country, has a history of inimical attitude towards the outsider. Insurgencies and regional groupings alike have thrived on those platforms. While the decade-long extensive contact with mainland India has considerably weakened such attitudes, the recent exodus might re-stoke such feelings. The victim of today might just turn the aggressor tomorrow.

Unfortunately, this reversal of globalisation could not have happened at a more inappropriate time, under a prime minister who has been credited with kick-starting the process of economic liberalisation in this country.

This article appeared at The New Indian Express and is reprinted with permission.