Growing US-China Military Rivalry: A Danger Of Spill-Over Into South Asia – Analysis

By Institute of South Asian Studies

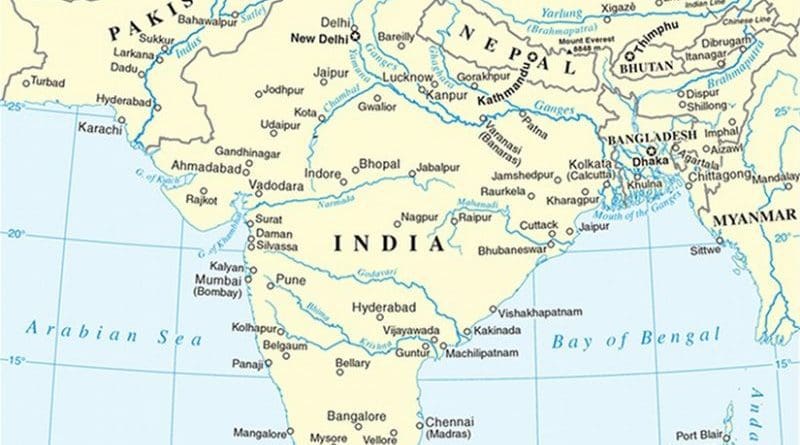

With Pakistan now choosing to act in a manner that might give the Chinese submarines access to its shores, and with India appearing to abandon its old non-alignment policy, there is a risk of the current US-China confrontation affecting South Asia.

By Shahid Javed Burki*

It does not suit South Asia to have the growing US-China military rivalry projected into the region. While it may help both Beijing and Washington to have that happen, it will result in setting the region back economically. As already argued in an earlier paper by me,2 it is essential that South Asian leaders recognise what is at stake.

The most likely theatre of conflict between China and the United States will be the seas along the Chinese coastline and the coastlines of the countries that choose to get aligned with it. South Asia has a long coastline, some of it in very sensitive areas, to which the protagonists in the developing Sino-US conflict will be attracted. South Asia should protect this asset, keeping in view regional interests rather than those of the individual countries.

Some analysts fear that the growing tension between the United States and China could conceivably lead to a military confrontation. “Uncertainty about what could lead either Beijing or Washington to risk war makes a crisis far more likely, since neither side knows when, where, or just how hard it can push without the other side pushing back”, wrote Avery Goldstein of the University of Pennsylvania in a 2013 Foreign Affairs article. “Should Beijing and Washington find themselves in a conflict, the US advantage in conventional forces would increase the temptation for Washington to threaten to or actually use force.

Recognizing the temptation facing Washington, Beijing might in turn feel pressure to use its conventional forces before they are destroyed. Although China could not reverse the military imbalance, it might believe that quickly imposing high costs on the United States would be the best way to get it to back off”. This is a game- theory approach to the making of policy in a contested area. “Getting Beijing and Washington to tackle the difficult task of containing a future crisis will not be easy. In the end it might take the experience of living through a terrifying showdown of the kind that defined early Cold War. But it should not have come to that”.3

There are a number of areas where such conflict could be the result. The first, of course, is the question of sovereignty. Washington is of the view that international law affords it freedom of navigation in international waters and airspace, defined in international law as lying beyond a country’s 12-mile territorial limit. China, on the other hand, wants to exclude foreign military vessels and aircraft from its 200-mile wide “exclusive economic zone”. Those crossing into this area will need Beijing’s authorisation, say the Chinese.

Washington, Tokyo and other capitals are not prepared to accept this claim. If they do, they would be kept out of much of South China Sea.

One of the most important lessons to be drawn from the old US-Soviet Cold War experience is the need for reliable communication between the senior leaders of the countries that may get engaged in a destructive confrontation because of faulty information. This was done by the creation of a hotline between Moscow and Washington. In 1998, China and the United States also set up a hotline, but the White House was not able to use it in a timely fashion in two cases – the 1999 bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade or the 2001 spy-plane incident. This may have happened because of the time needed by the political masters in Beijing to consult the military leadership. China has, as yet, to develop fully institutions such as the United States National Security Council that can coordinate its approach to crises.

Instead of direct communication between the top leadership in the two countries, Beijing may prefer to use some other forms of signalling. For example, the analysts Andrew Erikson and David Yang have referred to Chinese military writings that propose using the country’s anti-ship ballistic missile system, designed for targeting US aircraft carriers, to convey Beijing’s resolve during a crisis.

Some Chinese military thinkers have suggested that China could send a signal by firing warning shots intended to land near a moving US aircraft carrier or even by carefully aiming strikes at the command tower of a US carrier while sparing the rest of the vessel. But that would be a dangerous way to communicate, akin to playing with fire.

“The Chinese are interested in achieving an anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM) capability because it offers them the prospect of limiting the ability of other nations, particularly the United States, to exert military influence on China’s maritime periphery, which contains several disputed zones of core strategic importance to Beijing”, wrote Erikson and Yang. “ASBMs are regarded as means by which technologically limited developing countries can overcome by asymmetric means their qualitative inferiority in conventional combat platforms, because the gap between offense and defense is the greatest here”. 4

The development of ASBMS would be a paradigm shift since no other country possesses it. The United States relinquished a distantly related capability in 1988. According to a 2006 unclassified assessment by the United States Office of Naval Intelligence, China is equipping theatre ballistic missiles [TBMs] with manoeuvring re-entry vehicles [MaRVs] with radar-seekers to provide the accuracy necessary to attack a ship at sea. If such a capability is developed, it will be “extraordinarily difficult to defend against, whatever the ballistic missile the United States might deploy”.5

These developments should be put in the proper context. Geography is the major difference between the Cold War and a possible conflict between China and the United States in the 2010s. The former was focused on land; the latter is shaping up to be at sea. China is investing heavily in the development of a submarine fleet made up of two kinds of vessels. It has now a small number of nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines (SSBNS) and a larger collection of conventionally-armed attack submarines. Both are more secure when they remain close to the coast in the shallow waters where poor acoustics compromise the effectiveness of US undersea antisubmarine operations. Any attempt by these vessels to move into the deeper waters and away from the coastline would be interpreted by the United States as a hostile act and might react – or should react as the policy makers in Washington are being advised by several experts.

Even the normally calm magazine Foreign Affairs, the highly respected voice of the foreign policy establishment in the United States, has begun to carry articles that ask for a more robust response to China’s rise by the United States. In its issue of March/April 2015 the journal carried an article by Andrew Krepinevich suggesting how Washington could pre-empt what China is likely to do in Asia. “If Washington wants to change Beijing’s calculus, it must deny China the ability to control the air and sea around the first island chain (Japan, Taiwan and the Philippines), since the People’s Liberation Army would have to dominate both arenas to isolate the archipelago…Then there is the task of denying the PLA the sea control it would need to mount offensive operations against the islands”.6

Viewed from the South Asian perspective, there is one other difference between the large-power confrontation in the Cold War and one that is brewing in the early-21st century. India and Pakistan (the latter then included Bangladesh) did not opt for opposite sides; India, with a much larger presence in the sub-continent, decided not to choose at all. It remained neutral, inventing “non-alignment” as an ideology that several other countries in developing world found attractive. They followed India and became part of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). Pakistan, bothered then with a sense of insecurity as it is now too, chose to side with the power that could meet its pressing financial needs.

Those needs have not gone, but they can be met by a different source. In the Cold War Pakistan came to be closely aligned with the United States. The latter helped to build its military as well as its economy. This time, it has chosen to be with China, agreeing to a programme of development that may bring Beijing’s submarines to its shores. In the US$ 46-billion programme which it agreed to in April 2015 when Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Islamabad, the two sides included the further development of the deep- water port of Gwadar which can house submarines. At the same time Pakistan announced the purchase of eight boats for itself from the Chinese to expand its own fleet. India no longer appears to be interested in the NAM approach. It seems inclined, instead, to side with the United States, Japan and Australia in the developing Sino-American contest.

However, South Asia would do well to craft a regional approach towards this brewing conflict rather than have each country of the region follow its own narrow interests.

About the author:

* 1 Mr Shahid Javed Burki is Visiting Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore. He can be contacted at [email protected]. The author, not the ISAS, is responsible for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper. During a professional career spanning over half a century, Mr Burki has held a number of senior positions in Pakistan and at the World Bank. He was the Director of China Operations at the World Bank from 1987 to 1994, and the Vice President of Latin America and the Caribbean Region at the World Bank from 1994 to 1999. On leave of absence from the Bank, he was Pakistan’s Finance Minister, 1996-1997.

Source:

This article was published by ISAS as ISAS Brief Number 386 (PDF)

Notes:

2. Shahid Javed Burki, China and South Asia – I: “How the collapse of ‘Chimerica’ will affect South Asia”, Institute of South Asian Studies, Singapore.

3. Avery Goldstein, “China’s Real and Present Danger: Now is the time for Washington to Worry”, Foreign Affairs, September/October, 2013, p. 139.

4. Andrew S. Erikson and David D. Yang, “Using the Land to Control the Sea”, National War College Review, Vol. 62, No. 4, p. 53.

5. U.S. Navy Department, Seapower Questions on the Chinese Submarine Force, Washington DC.

6. Andrew Krepinevich, “How to deter China: The Case for Archipelagic Defense”, Foreign Affairs, March/April 2015, pp. 80-81.