Assessing The Future Of United Nations Peacekeeping – OpEd

Since the foundation of the United Nations peacekeeping has always been a “principle” activity. Since its foundation, the UN has carried out over 63 peacekeeping missions, out of which 17 continues to remain active even today. Since the evolution of UN from “crisis to crisis”, peacekeeping too continues to evolve particularly enriched with its 70 years of experience. Carrying out “multi-level operations” and vivid missions, ranging from ensuring “peace and stability” in global conflicts to providing “extensive” training mechanisms to military units of different nations in the world, the UN through multiple agencies, ensures that “stability, security and global order” is effectively maintained.

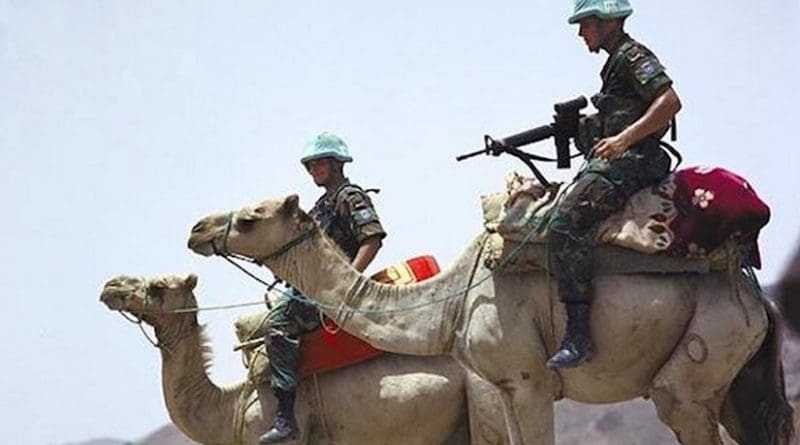

In the aftermath of Cold War, the international communities saw a sudden rise in peacekeeping missions, since the world was no longer divided into “blocs”, it became easier for United Nations Security Council to authorise peacekeeping missions “if and when” required. In the fall of 1990’s, the UN peacekeeping troops were deployed in Libya, Kuwait, Ethiopia and Eritrea to maintain “law and order” in a “conflict” rigged scenarios while ensuring “safety and security” of the masses.

In the later years, the United Nations Security Council also deployed “peacekeeping troops” commonly known as “blue berets” to prevent militant rebel factions in former Yugoslavia and Rwanda systematically carrying out “rape, genocide and ethnic cleansing”, while authorised designated task forces in Somalia, Haiti, Sudan among other nations. Most of these missions became popular not because of their “undesired” outcomes but because of their “failure” to fulfil the task they were sent to do. Policy makers must note that, the UNPROFOR mission (task force deployed in Bosnia) and UNAMIR (task force deployed in Rwanda) failed significantly, which not only resulted in “horrors and ethnic cleansing” within the state but largely occurred during the presence of UN “peacekeeping” troops.

Learning some major lessons during short time, the UN worked “relentlessly” to reduce such “horrific and horrendous” outcomes. This largely resulted in “extended” mandates and effective “response”: many UN peacekeeping troops deployed in respective mission are no longer limited to respond against an “eminent threat”, but are largely tasked to “defend” the mandate against all odds. This makes the “specific” troops deployed in the region “effective” against any “threat” posed by factions to them or to their mandate, while helps ensuring the “safety and security” of the peace process within the mission.

This approach is called “robust peacekeeping” or “positive active peacekeeping” which nonetheless received large “acceptance” from international communities, continues to face “significant” challenges today.

Hence, it is important for policy makers to ensure that the peacekeeping initiatives of UN remains effective, and with the assistance of security experts, think tanks and relevant agencies “adequately and effectively” address the challenges faced by the methodologies peacekeeping of today.

History So Far

Policy makers must note that, the history of peacekeeping is far too extensive hence, focusing on some of the major issues faced during “specific” missions seem to resolve the purpose. There have been two peacekeeping missions in particular that “highlights” certain challenges faced by peacekeeping forces while providing an extensive “insight” on UN peacekeeping of today.

United Nations Assistance Mission in Rwanda (UNAMIR)

The United Nations Security Council established UNAMIR through the Resolution 8726 which was passed during the Security Council session on 5th October 1993. The resolution was passed in support to the peace process in accordance to the Arusha Accords, the force established to ensure “peaceful distribution of power” between the Hutu government, the Tutsi rebels and Rwandese majority. There were significant limitations placed on the task force with guidelines in place to ensure that the mission does not instigate new scenarios of “violence” or genocide.

Within this context, UNAMIR came into action under the order of the United Nations Security Council to ensure the safety and security of masses residing in Kigali, to ensure that the ceasefire guidelines are respected, to monitor security during the phases of transition, while maintaining strict vigilance during elections, assist local security forces in clearing mines, and investigate any acts of “non-compliance” from signatory parties. Furthermore, the mandate highlighted the force to carry out humanitarian support and investigate any activities involving the masses with local law enforcement. It is important to note that, the mandate did not mention the force to “prepare” in an event of armed response. Within the early months of deployment, the force reached the “designated” personnel deployed to 2500, with subsequent troop contribution from Bangladesh, Ghana and Belgium.

During the early months in 1994, the then head of mission, Romeo Allaire was “briefed” with significant “intelligence” on rapid “militarization” of Hutus under the name of Hutu Power Movement. Furthermore, the task force discovered “significant” presence of from Tutsi’s in Kigali. By now, the UNAMIR, functioning under “limited resourced” budget, with sever obstruction from the Hutu government, and its consistent appeals to the United Nations HQ to extend the mission’s mandate, UNAMIR found itself in a position between rigid UNSC which in case of unsuccessful attempts to establish a new government would terminate the mission and rebel factions in the name of “militarily” armed Hutus rebels who were “regrouping” in large numbers in Kigali.

In the aftermath of President’s Habyarimana death, Dallaire took significant initiatives to increase the number of troops, but his requests were repeatedly refused, even after the reports of “mass killings” by Hutus reached UNHQ. Moreover, in the event involving the death of over 10 Belgium soldiers, Belgium withdrew his remaining troops from the force. In the wake of scenarios which “turning into genocides” UNAMIR was forced to defend the masses with few remaining cards in play. This peacekeeping force “passively” yet “silently” witnessed one of the largest genocide occurred in the history of mankind, they did what they could and watched.

United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) – Yugoslavia

In comparison to UNAMIR the UNPROFOR was a much larger force, equipped with over 39,000 troops. Also, the mission had to cover much larger grounds as compared to UNAMIR. The mission was initially created to ensure that the peace talks in Croatia continues in the wake of an “independence war”, the mission was soon tasked to cover Bosnia and Herzegovina, now tasked with another “mandate”.

The UNPROFOR presence in Bosnia and Herzegovina was largely limited to protect the masses of Sarajevo, while carrying out regular missions on humanitarian aid, protecting area with possible vulnerability while “closely” monitoring the Muslim-Croats.

On July 12th, 1995, a largely armed Bosnian Serbs “over-ran” the much designated “safe areas” of Srebrenica, which resulted in “mass killings” of Muslims. From UNPROFOR, a “lightly” armed “unequipped” Dutch battalion was present on the ground, was unable to provide “air-support” particularly when the UN “sure enough” to guarantee the safety of residing Muslims. In a similar situation faced by UNAMIR, UNPROFOR was lacking “vital resources” reinforced with a “poorly equipped” mandate limited UNPROFOR from “responding” to violent actors that not only pose a grave threat to their mission but also to the masses. Thus, UNPROFOR failed to perform the task it was “established” to do, which not only resulted in the deaths of millions, but also damaging the credibility of the United Nations as a “peacekeeper”.

Policy makers must note that, the aforementioned arguments and comparison of different missions are not limiting the UNPROFORs tasks. The reference here is not to understand the complex situation discussing the aftermath of Yugoslav break up or to provide a complete analysis of the situation.

Changing trends in Peacekeeping

Dependency on a “robust” Peacekeeping

In the light of UN peacekeeping missions “operations tactics” in the last few decades, the peacekeeping operations have been drafted majorly to deal with “inter-state” conflicts. This application of “traditional” pre-Cold War tactic proved disastrous in major missions carried out by the UN.

The aftermath of “ethnic cleansing” incidents in Yugoslavia and Rwanda, the UN, carried out significant “post-damage assessment” which later emerged as “Brahmi report”, which it then extensively deliberated during the UN Security Council session of 2000. One of the key terminology used in the report was “robust peacekeeping” which the UN “extensively” used and further redefined it within the context of “impartiality” in accordance to the UN Charter. The UN noted that treating all violators of “peace agreements” as equal could further adversely affect the “stability and security of the mission” which could then instigate “worst horrors and atrocities”.

Since its initial findings followed by immense support from international communities, the “robust peacekeeping” policy has been effectively used in today’s peacekeeping missions. Many policy makers within the UN, particularly Jean-Marie Guéhenno, who served as Under Secretary General of Peacekeeping from 2000 to 2008, strongly supported this “concept”. Practically, robust peacekeeping involves peacekeeping troops to use force against violent actors that creates hinderance in peace, this is largely effective in cases when the factions are violent non-state actors. According to the UN, the violent non-state actors are those who are likely to “abide by their word” in comparison to state actors. This “concept” is largely “effective” and “successful” where the consent of multiple actors/parties are not required particularly from those actors that play a larger role in the conflict.

Policy makers must note that, the concept of robust peacekeeping is largely interlinked with the Responsibility to Protect doctrine. Although, the priority for the doctrine is to ensure that these missions largely remain “equipped with sufficient necessary resources” in an effort to enable them in responding adequately and freely irrespective of scenarios and effectively maintain a “control” over the situation.

Unaddressed issues

The “concept” of robust peacekeeping continues has its own challenges. There is always a thin line for particularly for the UN between an “intervention”, “appropriate intervention” and “inappropriate”, the latter playing the role of a “participator” in an active conflict. This puts a “target on the back” of peacekeepers, which results in excessive loss of lives: according to UN Secretariat, over 100 peacekeepers have been killed in peacekeeping missions between 2008 and 20015, with losses as high as 173 in 2010.

Furthermore, the solution does not lies in “aggressive” peacekeeping which primarily will not receive support from majority nations – the US, who remains to be the sole supporter of this “concept”, significantly found that, major contributors in peacekeeping particularly India will not risk the lives of their soldiers by exposing them to a greater, much greater risk during conflicts. Hence, this has been largely affecting the peacekeeping forces of United Nations Assistance Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) and United Nations Assistance Mission in South Sudan (UNAMISS) were reluctant to face the government forces.

Moreover, the majority issues are caused by disagreements within the policy makers at UN in particular with “their” concept to robust peacekeeping coupled by a saga of “disagreements” that comes from major contributors of peacekeeping forces.

Furthermore, the “concept of humanitarian assistance” has not always been a positive “benefactor” for robust peacekeeping. Particularly in Congo, the NGO’s continue to face enormous difficulty in separating them from the actions by the UN, particularly the peacekeeping force are tasked to clear the regions occupied by the rebel groups. The issue gets further complex when UN does not treat all the parties equally, which means that the UN is not involving all parties to the dialogue sessions, forcing the humanitarian agencies particularly the NGOs to establish independent contact with such “neglected” parties, which then reinforces the challenges faced by NGOs.

A negative response from the ground

Policy makers must note that, the outcome of “robust peacekeeping” has not always been positive. One such example can be taken from the UN mission still active in Democratic Republic of the Congo, MONUSCA, “failed” to establish peace and security, irrespective of its mandate. This forced the United Nations Security Council to initiate an “intervention” task force in accordance with the United Nations Security Council Resolution 2098, which stated the need to eliminate and disarm rebel militant factions operating in the region. Many policy makers within the UN were skeptical about the “vulnerability” of such mission since the approach was “aggressive”.

The outcomes received by intervention task force through “aggressive” approach was not positive. The mandate of the mission was extended for a third time in 2016. The peacekeeping troops majorly contributed by South Africa, Tanzania and Malawi, the peacekeeping force successfully defeated the Congo’s largest rebel groups M23 in just three months from their first arrival. Since then, there has not been any major successes majorly because of the political complexities. M23, has been “allegedly” receiving support from Rwanda, which share a “complex” relationship with the two-major troop contributing nations, South Africa and Tanzania. The two nations, on the contrary, strongly support the Democratic Republic of Congo president Joseph Kabila. This “intervention task force” highlights the sheer “robustness” and “aggressiveness” of peacekeeping missions are “severely” compromised by complexed situation which involves by actors with “deep rooted” interests.

Conclusion

Policy makers must note that, the current scenario implied with the evolving “concept” peacekeeping need further research and understanding before it can be implemented in practice. Most of these new concepts are theoretical in nature, cannot be implemented in practice. Moreover, the conflicts scenarios of today are evolving and coupled with the evolution in technology, these conflicts instigate the rise of “never seen” challenges peacekeeping initiatives.

Hence, policy makers must take “absolute” care while implementing certain policies or deriving a new “concept” particularly on peacekeeping initiatives since peacekeeping mechanism is not just about saving lives rather stands today as a “guardian” of democratic values and peace.

*Anant Mishra is a former Youth Representative to the United Nations. He had previously served with the United Nations Security Council, the United Nations General Assembly as well as the Economic and Social Council. His previous assignments were in Rwanda and Congo. He also serves as a visiting faculty for numerous universities and delivers lectures on conflict and foreign relations.