Vietnam’s Booming E-Commerce Market – Analysis

By ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute

By Dang Hoang Linh*

INTRODUCTION

According to UNCTAD (2019), the total value of global e-commerce increased from US$16 trillion in 2013 to more than US$29 trillion in 2017.1 Recent research by Google and Temasek Holdings predicts that Southeast Asia will witness remarkable growth in e- commerce sales, increasing by more than three times to reach a total of US$240 billion by 2023.2 Although e-commerce in Vietnam significantly lags behind that in Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand, the country is no longer a stranger to e-commerce. Vietnam is in fact considered the fastest-growing digital economy in the region and its dynamic e-commerce market is unlocking new business opportunities and receiving great attention from both domestic and foreign investors.

Over the past few years, Vietnam’s internet economy has received large foreign investment, placing it just behind Indonesia and Singapore, with investment inflow still on an unprecedented rise.3 Over the last four years, approximately US$1 billion in funding has been poured into Vietnam’s e-commerce sector, reaching a record high in 2019.4 The period 2018-2019 also witnessed the emergence of Vietnam-origin e-commerce players, such as Tiki, Thegioididong and Sendo, which are among the most successful e-commerce platforms in the region.

These outcomes show that despite obstacles in physical, digital, and legal infrastructure, Vietnam is one of the most promising e-commerce markets, driven as it is by its young population, growing middle class, high internet penetration, and rising smartphone penetration.

RISING E-COMMERCE TIGER IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

In revenue terms, the growth rate (CAGR) of e-commerce in Vietnam surged 30 per cent in 2018 to reach a new high of about US$8 billion.5 This growth rate is higher than that of Thailand and Malaysia.6 User penetration was recorded at about 56.7 per cent in 2019 and is expected to reach 64.4 per cent in the next four years.7 In parallel with the fast pace of economic growth, the scale of Vietnam’s e-commerce market progressed from a low starting point of about US$4 billion in 2015 to about US$7.8 billion in 2018. E-commerce expenditure per capita amounted to US$65 in 2018, registering a growth of 29 per cent compared to 2017, and coming a close third in global rankings.8

Vietnam’s two biggest cities, Hanoi and HCM City, respectively own 154,221 and 159,379 websites with .vn domain names, and together account for 70 per cent of the country’s total e-commerce transactions.9 Other localities have much fewer websites and the scale of e- commerce in rural and remote areas is negligible. Some 70 per cent of the population lives in rural areas.

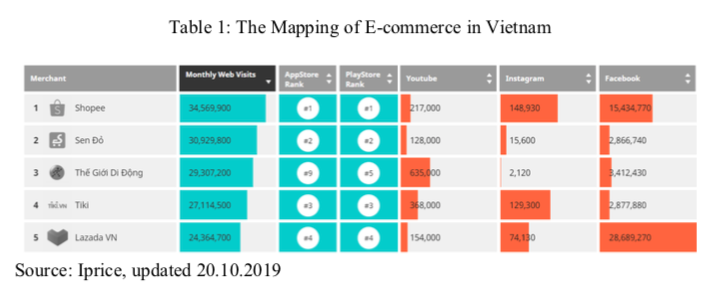

As of 2018, five of the 10 most successful Southeast Asian e-commerce platforms operate in Vietnam – namely Lazada, Shopee, Tiki, Thegioididong, and Sendo.10 In Vietnam, Shopee occupies the number one spot with about 16.8 per cent share of combined monthly web traffic and ranking first in terms of mobile application usage, closely followed by Tiki, Lazada, Sendo and Thegioididong (see Table 1: 2nd, 3rd and 4th column).11 Nevertheless, Lazada VN far surpasses other competitors regarding social media marketing on YouTube, Instagram and Facebook (see Table 1: the last three columns). Notably, as Tiki, Sendo, and Thegioididong only operate in the country, their success offers concrete evidence of the huge potential of Vietnam’s e-commerce sector. The impressive footprint of these platforms is fuelled by the huge inflow in recent years of foreign funding, mainly from Japan, Germany, the United States, Korea, China, and Singapore investors. For example, Sendo.vn received US$51 million from Japan’s SBI Holdings in 2018 while China’s JD.com became the largest investor in Tiki.12

Regarding Vietnamese consumer shopping habits, about 71 per cent of e-commerce transactions are made from desktop computers while 18 per cent of purchases take place on a mobile device.13 Due to low banking penetration, Vietnam has the smallest number of merchants offering credit card payment in Southeast Asia. The most popular payment method is cash on delivery (COD), and up to 60 per cent of merchants opts for hiring shippers or self-delivery to collect COD payments. In addition, only 15 per cent of users with a bank card made purchases online in 2016 while approximately 70 per cent of sellers are able to offer payment with credit cards.14 Clothing and footwear are the most popular online purchases, followed by electronics and refrigerators, then mother and baby care products.15

Logistics and delivery services have a close relationship with online businesses. Along with the fast pace of growth of e-commerce in 2018, the logistics and delivery businesses saw a phenomenal growth rate of 70 per cent amid intense competition16. At the same time, there was an increase in investment and application of advanced technologies, such as automatic item sorting system and big data, in these two sectors. Vietnam Post and Viettel Post are the leading delivery service providers, followed by EMS, Giao Hang Nhanh, and Giao Hang Tiet Kiem. Notably, in the e-commerce centres of Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, fast delivery services have started to grow quickly with the rise of some well-known brands, e.g. GrabFood, GoViet, and Now.vn. It is also worth noting that since 70 per cent of Vietnam’s citizens live in rural areas, deliveries might also need to be made to scattered and distant rural customers.

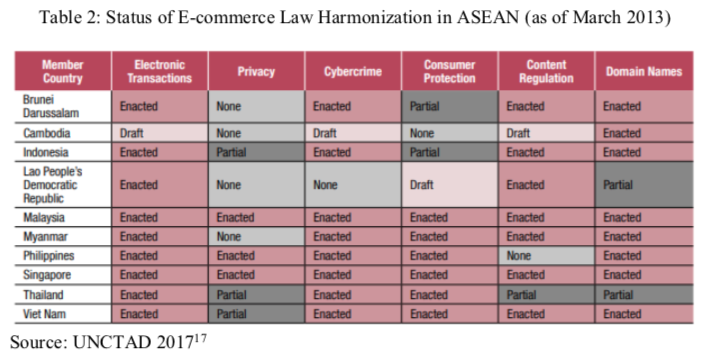

Regarding the supporting legal framework, Table 2 shows that compared to other ASEAN countries, Vietnam has a relatively favourable legal environment for the development of e- commerce, with five out of six main laws fully enacted to regulate e-commerce activities. Notably, Decree No.52 paved the way for the high growth rate of the retail e-commerce market by regulating the development, application, and management of e-commerce activities. Moreover, enabled by Decision no. 1563/QD-TTg issued by the prime minister in August 2016, an ecosystem of transportation, delivery, and fulfilment services is currently being built for the e-commerce sector throughout the entire country. This ecosystem will gradually expand to the region to facilitate cross-border transactions. The new Cybersecurity Law, which took effect in early 2019, requires global technology companies such as Google and Facebook to open offices and store users’ important personal data locally in Vietnam. This law is essential to fight cybercrime. To promote cross-border transactions, the government has joined 13 Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) and is negotiating 3 others, as of 2019.

POTENTIAL

Vietnam’s e-commerce market has taken off due to the fundamentals in place for an exponential growth of e-commerce, fuelled by massive investments from key retail players.

The country’s 2018 GDP is about US$250 billion and is predicted to reach a trillion USD by 2035.18 Nominal per-capita income is predicted to increase by 54 per cent in 2024 (US$3,952) in comparison to 2018 (US$2,551).19 About 26 per cent of its population, compared with only 13 per cent today, is estimated to join the global middle-income class with consumption of at least US$15 a day by 2026.20 Therefore, it is projected that Vietnamese consumers will spend more and more online. They are easily influenced by word-of-mouth and social media, and are quick to react to external influence.

Vietnam has a large population which is forecast to hit 100 million in 2024.21 Correspondingly, the number of internet users in Vietnam has increased rapidly. There are 59 million internet users in Vietnam as of 2019, well over half the total population and ranking it at 2nd in Southeast Asia.22 This number is estimated to hit 76 million by 2023. Connected consumers, identified by their regular use of the internet and willingness to pay, are potential influencers in the digital economy. According to Nielsen, the number of connected consumers in Vietnam is expected to rise from 23 million people in 2017 to 40 million in 2025, thanks to the sustained economic growth and infrastructure improvement.23

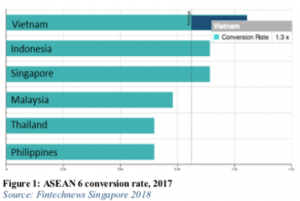

According to the 2019 Global Digital Report, the average Vietnamese spends an average of 6 hours 42 minutes a day online (both on computer and mobile devices), just above the global average but behind the Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia.24 However, Vietnam also witnessed the sharpest increase in mobile traffic across Southeast Asia in 2017, as well as the highest conversion rate.25 Mobile traffic increased by 19 per cent in 2017, comprising 72 per cent of the overall traffic.26 Millennials’ increasing use of mobile phones is considered the key factor driving this growth, as this group makes up more than 30 per cent of Vietnam’s population.

Vietnam’s average conversion rate is 30 per cent higher than the average level of ASEAN 6. This is partly due to it having the lowest basket size in the region (US$23 in 2017)27 – customers order low-value items without an intent to return what is ordered. The promotion of the online-to- offline model is also one of the contributors to this high conversion rate since consumers can first examine the products in physical stores before making a purchase via a website.

Although COD remains the most popular payment method, bank transfers are increasingly popular in Vietnam as the country heads toward a cashless economy. Digital payment platforms, including Payoneer, actively invest in developing logistics and infrastructure in the country, and aim to provide secure payment solutions for businesses. In early 2017, a cashless plan was introduced by the government to promote electronic payment methods and reduce cash transactions to below 10 per cent of the total market transactions by 2020,28 thus encouraging consumers to shop more online. Within the next three years, an automatic payment centre might also be established to promote interaction between consumers and online payment facilities. Importantly, customers’ payment habits are changing. Consistent with a trend across many Southeast Asian countries, Vietnamese consumers have increasingly adopted mobile wallets, with 47 per cent of internet users already using a mobile payment service monthly, surpassing the global average.29 Payment app Momo is among the most popular e-wallets in Vietnam, with about 10 million customers – a tenfold increase in the last two years.30

The great potential of Vietnam’s e-commerce sector can be seen via its enormous expansion, which is predicted to reach US$15 billion in terms of revenue in 2020.31 If the e-commerce market can keep its current growth rate of 30 per cent, its market size might hit US$33 billion by 2025 and Vietnam’s e-commerce market will rank third in Southeast Asia, after Indonesia with US$100 billion and Thailand with US$43 billion.32

CONSTRAINTS

Despite its vast potential, Vietnam’s e-commerce market has to grapple with a number of obstacles. Regarding consumers’ habits, Vietnamese consumers, especially the younger generation, are particularly fond of purchasing goods on popular foreign e-commerce websites such as Amazon or eBay due to their sound reputation and wide range of products. In contrast, most Vietnamese enterprises are still underperforming compared to many global online providers. They have not properly invested in researching customer tastes, and the quality and design of domestic products are sometimes still inferior to similar products made in other countries. Hence, the entry of Amazon into the Vietnam market in early 2019 has put firm pressure on existing domestic e-commerce players. Vietnam’s e-commerce market will thus soon witness even fiercer competition.

Domestic and international traders using e-commerce to cheat, sell counterfeit goods, infringe intellectual property rights, and even trade banned goods have reached an alarming level.33 Online fraud such as stealing information, data, and bank accounts have put e- commerce under the spotlight, further affecting the growth of a strong and healthy digital economy. These unsafe online transactions have made consumers wary of making online purchases.

The Vietnam E-commerce Report 2019 showed that up to 50 per cent of respondents were dissatisfied with online transactions,34 while another report by the Department of E- commerce and Information Technology indicates that the majority of respondents were concerned about the poor quality of products, with a huge disparity between what was advertised and delivered.35 Other factors behind consumers’ preference for traditional shopping include the relative similarity in terms of price between online products and those from physical stores (especially those on special promotions), fear of leaked personal information, the easier and faster shopping experience at stores, no bank card required for physical stores, and the relatively complicated online purchasing process. Another factor is that despite its vibrant economy and business opportunities, Vietnamese continue to be the most avid savers in the Asia-Pacific region.36

To be sure, the e-commerce platforms in Vietnam have been able to provide consumers with many payment options such as payment via bank transfer, COD, and payment via e-wallet. However, COD still accounts for the highest share of total transactions, hindering the transformation of the e-commerce market in Vietnam.

The relatively new and rapidly growing e-commerce sector has posed challenges to the government’s ability to create a conducive legal and policy framework. The legal guidelines in this area are not sufficiently comprehensive and robust, especially those related to cross- border e-commerce. The accelerated development of digital technologies has led to countless new e-commerce models. Additionally, cross-border transactions and services are carried out more often, varying in terms of participants and complicated in the way they operate. Although many legal documents have included provisions on the protection of personal information,37 the illegal collection, use, distribution, and trading of personal information still happens. The risk of illegal collection, use, distribution, and trading of personal information is one of the reasons for consumers’ lack of confidence in e-commerce. Consumers are still awaiting positive results from the enforcement of the Law on Cybersecurity.38 The government also faces challenges in administering taxes on e- commerce activities. Unlike traditional businesses with physical stores and specific addresses, it is difficult to verify the identity of sellers or monitor sale transactions in a network environment. Up to now, this activity still mainly depends on the willingness of individuals and businesses to declare transactions, address information, and personal tax identification numbers for the tax agency to ascertain tax payments. Moreover, the tax agency does not have sufficient expertise and authority to handle related networks, information, and communication systems.

Inadequate technology infrastructure is also considered one of the key challenges for businesses engaged in e-commerce, including security concerns, bandwidth availability, and integration with existing protocols. The Inclusive Internet Index 2019 ranked Vietnam 44th out of 95 globally, and 5th among eight Southeast Asian countries.39 The index’s Availability ranking shows that Vietnam owns a weak digital infrastructure (54th),40 while its Affordability ranking (53rd) indicates a relatively high cost of access relative to income and the level of competition in the internet marketplace.

Poor technology infrastructure not only makes it difficult for Vietnam’s e-commerce to compete with that of other developing countries, but also causes unwanted incidents or network security issues. For example, according to Lazada’s statistics, the disruption of the AAG cable network for more than 2 weeks in 2016 caused a loss of up to 30 per cent of Lazada’s average revenue per day.41 Last but not least, high shipping costs and traffic congestion are factors that hamper the growth of e-commerce. Huge logistics costs, which account for 60-70 per cent of online retailers’ revenues, were the main cause of business losses.

Handling COD payments via self-delivery or hiring shippers leads to high operation costs, late deliveries, and slow transactions due to external factors such as traffic congestion and other bad transport conditions. Large e-commerce firms also need massive warehouses and hundreds of staff members to handle daily tasks.

That the majority of the Vietnamese population is still dispersed across distant and scattered rural areas might make it more expensive and difficult for the operation of fast delivery, thus impacting the online shopping sector. This mainly stems from a relative lack of efficient retail channels connecting major urban locales to remote and rural areas.

Vietnam also has a wide digital divide amongst regions which, instead of declining, has been increasing.42 In fact, rural areas that comprise the majority of the country’s population is potentially a large consumption market as well as an ample supplier of different products for the e-commerce market. Such wide digital gaps will not only hinder the healthy growth of e-commerce but also threaten the long-term sustainable development of the whole economy. In more industrialised countries in the region, such as Malaysia and Thailand, the difference in per-capita spending between urban and non-urban areas is about three to four times whereas this spread is over fivefold in Vietnam. The case is similar when it comes to living standards and infrastructure gaps.43 Meanwhile, legal and policy support for developing e-commerce in remote and mountainous areas remains modest.

Regarding operational challenges, e-commerce is not the playground for businesses with weak financial, technological, and management capacities. In a similar vein, costs needed to set up an e-commerce business and the shortage of skilled staff can cause much hardship to a start-up. The major challenge, however, does not lie in the complexity of platforms or interface design, but in the lack of a skilled workforce to conduct online transactions and related technology. 44 Another challenge stems from obsolete warehouse operation technology – only one-third of e-commerce businesses own modern warehouse management systems that can be integrated with online platforms. This explains the high inventory and warehouse management costs which, in many businesses, amount to more than 20 per cent of total revenue.

SOME RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

Vietnam enjoys several advantages that aid the growth of its e-commerce market. It has a large and young population with growing incomes, growing consumer confidence with high conversion rate, expanding mobile adoption and internet penetration, as well as the prevalence of social media. However, many factors affect profitability, such as low consumer confidence in online purchases, limited logistics and delivery services, weak physical and digital infrastructure, insufficient legal framework, as well as the wide digital gap amongst regions.

There is a huge demand for online shopping among Vietnamese consumers. Despite the preference of young Vietnamese consumers for foreign e-commerce websites, the greater understanding of customer preference, needs, and shopping habits is on the side of domestic e-commerce providers. To gain consumer trust, domestic e-commerce businesses should promote the provision of products with clear/certified origins and control fake and shoddy goods on their platforms. A programme that traces product origin is one recommendation, which can also be a means to promote themselves in a transparent manner. Besides, e- commerce players should develop their own infrastructure to adapt to new challenges, ranging from order processing systems, warehouse capacity, to the speed of transportation. One of the main driving forces of e-commerce in recent years can be attributed to the development of advanced telecommunication technologies such as 4G as well as artificial intelligence and machine learning.

As e-transactions gain in popularity, it is essential to ensure payment system reliability and protect customer private information. This requires collaboration between companies and the government on administration, maintenance, and risk management aspects. Promoting the use of mobile payment could be considered as the way forward for Vietnam, which has a relatively low rate of banking penetration but relatively fast-growing smartphone penetration, especially in rural areas.45

Vietnam should also regularly review and update its legal system as well as strengthen its law enforcement. A special organisation that serves as a state management agency should be established to handle incidents, e.g. cybersecurity issues, which arise from the development of the digital economy. To narrow the digital gap amongst regions and promote long-term sustainability, policies should aim to provide e-commerce with an efficient network of transport and delivery services to improve the order fulfilment process. This can be enabled via upgrading physical and digital connections amongst urban and non- urban populations as well as within non-urban areas. This network can then serve as a basis to expand and promote cross-border e-commerce transactions. In addition, as cross-border e-commerce transactions take place more often, promoting close relationships with ASEAN countries in terms of law harmonisation is a must.

Closer and more harmonious coordination between the related state management agencies, businesses, consumers, and professional organisations is key in improving the e-commerce environment in Vietnam.

*About the author: Dang Hoang Linh, is Dean and Senior Lecturer of the Faculty of International Economics, Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam.

Source: This article was published by ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute as ISEAS Perspective 2020, No. 4

Notes:

1 See UNCTAD. (2019). Global e-Commerce sales surged to $29 trillion. Press Release.

https://unctad.org/en/pages/PressRelease.aspx?OriginalV ersionID=505

2 See Google and Temasek Holdings. (2019). “e-Conomy SEA 2019: Swipe up and to the right:

Southeast Asia’s $100 billion internet economy”. https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/intl/en-

apac/tools-resources/research-studies/e-conomy-sea-2019-swipe-up-and-to-the-right-southeast-

asias-100-billion-internet-economy/

3 See Van Linh. (2019). “Thương mại điện tử chờ bùng nổ”. Thoi Bao Kinh Doanh.

https://thoibaokinhdoanh.vn/thi-truong/thuong-mai-dien-tu-cho-bung-no-1062715.html

and Google and Temasek Holdings. (2019).

4 Google and Temasek Holdings. (2019).

5 See EBI Report. (2019). “Vietnam E-Business Index 2019”. Vietnam E-commerce Association.

6 Google and Temasek Holdings. (2019).

7 See Statista. (2019). “Vietnam Ecommerce Outlook”.

https://www.statista.com/outlook/2”43/127/ecommerce/vietnam.

8 Google and Temasek Holdings. (2019).

9 See Dtinews. (2018). “Vietnam has a huge e-commerce potential”.

http://dtinews.vn/en/news/018/55936/vietnam-has-huge-e-commerce-potential.html.

10 See Techinasia. (2019). “3 Vietnamese platforms among most visited ecommerce sites in SE

Asia”. https://www.techinasia.com/3-vietnamese-platforms-visited-ecommerce-sites-sea.

11 See Iprice. (2019). “The Map of E-commerce in Vietnam”.

https://iprice.vn/insights/mapofecommerce/en/.

12 See Dang Dang Truong (2018). “Báo cáo tổng kết thương mại điện tử Việt Nam năm 2018”.

https://iprice.vn/xu-huong/insights/bao-cao-tong-ket-thuong-mai-dien-tu-viet-nam-nam-2018/.

13 EBI report. (2019).

14 See Ly Pham. (2018). “3 Insights About Vietnam’s Ecommerce Landscape Last Year”.

Techinasia.

https://www.techinasia.com/talk/vietnam-ecommerce-facts-2017

15 See EBI report. (2019).

16 Ibid.

17 UNCTAD (2017). E-Commerce: Global trends and Developments. Division on Technology and

Logistics

18 See World Bank. (2019). http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/vietnam/overview, and

World Bank, Vietnam Ministry of Planning and Investment. (2016). Vietnam 2035: Toward

Prosperity, Creativity, Equity, and Democracy. Washington, DC: World Bank.

19 See IMF. (2019).

https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPDPC@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/V

NM

20 See World Bank. (2019).

21 See Statista. (2019). “Vietnam total population”.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/444597/total-population-of-vietnam/.

22 See Statista. (2019). “Number of Internet Users in Vietnam from 2017 to 2023 (in millions)”.

23 See Nielsen. (2019). Report: What’s next in South East Asia.

24 See We Are Social and Hootsuite. (2019). “2019 Global Internet Use Accelerates”. https://wearesocial.com/blog/2019/01/digital-2019-global-internet-use-accelerates.

25The conversion rate is the percentage of users who take a desired action, i.e. the percentage of website visitors who buy something on the site.

26 See FintechNews Singapore. (2018). “E-Commerce in SEA Study: Vietnam Leads In Conversion Rate; Singapore Is The Biggest Spender”. https://fintechnews.sg/17834/fintech/e- commerce-in-sea-study-vietnam-leads-in-conversion-rate-singapore-is-the-biggest-spender/.

27 Iprice (2017). “State of eCommerce in Southeast Asia 2017”. https://iprice.my/insights/stateofecommerce2017/

28 See OECD. (2018). “SME Policy Index: ASEAN 2018: Boosting Competitiveness and Inclusive Growth”. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/9789264305328-25- en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/9789264305328-25-en.

29 See Global Web Index. (2019). “Mobile Payment: Examining the mobile payments industry and its impact on the financial sector”. GlobalWebIndex Trends Reports.

30 See Dean Dougn. (2019). “Vietnam is experiencing a boom in mobile payments”. Vietnaminsider. https://vietnaminsider.vn/vietnam-is-experiencing-a-boom-in-mobile-payments/. 31 See Loc Truong. (2019). “E-commerce revenue forecast to hit $15 bn in 2020.” Vietnaminsider. https://vietnaminsider.vn/e-commerce-revenue-forecast-to-hit-15-bn-in-2020/.

32 EBI Report. (2019).

33 See Hai Linh. (2019). “Không nương tay với buôn lậu và gian lận thương mại”. Thời Báo Tài Chính Việt Nam. http://thoibaotaichinhvietnam.vn/pages/nhip-song-tai-chinh/2019-07-31/khong- nuong-tay-voi-buon-lau-va-gian-lan-thuong-mai-74538.aspx.

34 Vinaresearch. (2018). “Báo Cáo Nghiên Cứu Thói Quen Sử Dụng Mạng Xã Hội Của Người Việt Nam 2018”. https://vinaresearch.net/public/news/2201-bao-cao-nghien-cuu-thoi-quen-su- dung-mang-xa-hoi-cua-nguoi-viet-nam-2018.vnrs and Van Linh. (2019).

35 See Department of E-commerce and Information Technology (2015). Vietnam Ecommerce Report. The Ministry of Industry and Trade, and EBI report. (2019).

36 See Nielsen. (2019). Quarter by number Q1/2019. GLOBAL LITE REPORT.

37 For example, the Civil Code, the Law on Information Technology, the Criminal Code, the Law on Network Information Security and the Decree on E-Commerce, Decree prescribing sanctions against administrative violations in the fields of post, telecommunications, information technology and radio frequency (EBI 2019).

38See Tran Anh Thu (2018). “Phát triển thương mại điện tử ở Việt Nam trong bối cảnh kinh tế số” Tap Chi Tai Chinh. http://tapchitaichinh.vn/tai-chinh-kinh-doanh/phat-trien-thuong- mai-dien-tu-o-viet-nam-trong-boi-canh-kinhte-so-138944.html.

39 See the Inclusive Internet Index 2019 of The Economist.

https://theinclusiveinternet.eiu.com/explore/countries/performance?category=overall.

40 Represents quality and breadth of available infrastructure required for access and levels of

Internet usage.

41 Tran Anh Thu. (2018).

42 EBI report. (2019).

43 Google and Temasek Holdings. (2019)

44 See Reid Kirchenbauer (2019). “E-Commerce in Southeast Asia: Major Challenges”.

https://www.investasian.com/2016/04/04/e-commerce-asia-challenges/.

45See Google and MMA. (2019). “The State of Mobile in Rural Vietnam Report”, p. 3.