Iran’s Foreign Policy – Analysis

By CRS

By Kenneth Katzman*

This report provides an overview of Iran’s foreign policy, which has been a subject of numerous congressional hearings and of sanctions and other legislation for many years. The report analyzes Iranian foreign policy as a whole and by region. The regional analysis discusses those countries where Iranian policy is of U.S. concern. The report contains some specific information on Iran’s relations with these countries, but refers to other CRS reports for more detail, particularly on the views of individual countries towards Iran.

This report does not examine Iran’s broader policy toward the United States of U.S.-Iran relations in detail, but the present report analyzes Iran’s actions in relations to U.S. interests as a consistent theme. Nor does this report address how a potential Iranian nuclear weapon factors into Iran’s foreign policy.

Iran’s Policy Motivators

Iran’s foreign policy is a product of overlapping, and sometimes contradictory, motivations. In describing the tension between some of these motivations, one expert has said that Iran faces constant decisions about whether it is a “nation or a cause.”1 Iranian leaders appear to constantly weigh the relative imperatives of their government’s revolutionary and religious ideology against the demands of Iran’s interests as a country. Some of the factors that affect Iran’s foreign policy actions are discussed below.

Threat Perception

Iran’s leaders are apparently motivated, at least to some extent, by the perception of threat to their regime and their national interests posed by the United States and its allies.

- In spite of statements by U.S. officials that the United States does not seek regime change in Iran, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamene’i has repeatedly stated that the United States has never accepted the Islamic revolution and seeks to overturn it through various actions such as support for domestic opposition to the regime, imposition of economic sanctions, and support for armed or other action by Iran’s regional adversaries.2

- Iran’s leaders assert that the U.S. maintenance of a large military presence in the Persian Gulf region and in other countries around Iran could reflect U.S. intention to attack Iran if Iran pursues policies the United States finds inimical, or could cause military miscalculation that leads to conflict.3

- Some Iranian official media have asserted that the United States not only supports Sunni Arab regimes and movements that criticize or actively oppose Iran, but that the United States has created or empowered radical Sunni Islamist extremist factions such as the Islamic State organization.4

Ideology

The ideology of Iran’s 1979 Islamic revolution continues to influence Iran’s foreign policy. The revolution overthrew a secular authoritarian leader, the Shah of Iran, who the leaders of the revolution asserted had suppressed Islam and its clergy. It established a clerical regime in which ultimate power is invested in a “Supreme Guide,” or Supreme Leader, who combines political and religious authority.

- In the early years after the revolution, Iran attempted to “export” its revolution to nearby Muslim states. As of the late 1990s, Iran apparently has abandoned that goal because promoting it succeeded only in producing resistance to Iran in the region.5

- Iran’s leaders assert that the political and economic structures of the Middle East are heavily weighted against “oppressed” peoples and in favor of the United States and its allies, particularly Israel. Iranian leaders generally include in their definition of the oppressed the Palestinians, who do not have a state of their own, and Shiite Muslims, who are minorities in many countries of the region and are generally underrepresented politically and disadvantaged economically.

- Iran claims that the region’s politics and economics have been distorted by Western intervention and economic domination, and that this perceived domination must be ended. Iranian officials typically cite the creation of Israel as a manifestation of Western intervention that, according to Iran, deprived the Palestinians of legitimate rights.

National Interests

Iran’s national interests also shape its foreign policy, sometimes intersecting with and complicating Iran’s ideology.

- Iran’s leaders, stressing Iran’s well-developed civilization and historic independence, claim a right to be recognized as a major power in the region. They often contrast Iran’s history with that of the six Persian Gulf monarchy states (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, and Oman) that make up the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), several of which gained independence in the early 1970s. On this point, the leaders of the Islamic Republic of Iran make many of the foreign policy assertions and undertake many of the same actions that were undertaken by the former Shah of Iran and Iranian dynasties prior to that.

- In some cases, Iran has appeared willing to temper its commitment to aid other Shiites to promote its geopolitical interests. For example, it has supported mostly Christian-inhabited Armenia, rather than Shiite-inhabited Azerbaijan, in part to thwart cross-border Azeri nationalism among Iran’s large Azeri minority. Iran also has generally refrained from backing Islamist movements in the Central Asian countries, reportedly in part to avoid offending Russia, its most important arms and technology supplier and an ally in support of Syrian President Bashar Al Assad.

- Even though Iranian leaders accuse U.S. allies of contributing to U.S. efforts to structure the Middle East to the advantage of the United States and Israel, Iranian officials have sought to engage with and benefit from transactions with U.S. allies to try to thwart international sanctions.

Factional Interests

Iran’s foreign policy often appears to reflect differing approaches and outlooks among key players and interests groups.

- By all accounts, Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamene’i, has final say over all major foreign policy decisions. Khamene’i is widely considered an ideological hardliner who expresses deep-seated mistrust of U.S. intentions toward Iran. His consistent refrain, and the title of a book widely available in Iran, is “I am a revolutionary, not a diplomat.”6 Leaders of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), a military and internal security institution created after the Islamic revolution, consistently express support for Khamene’i and ideology-based foreign policy decisions.

- Khamene’i has tacitly backed the JCPOA – if only by not openly opposing it – but he has stated on several occasions since it was finalized that neither Iran’s foreign policy nor its commitment to opposing U.S. policy in the region will not change as a result of the JCPOA. The IRGC leadership has criticized the accord but not threatened to undermine it, and has made statements similar to those of Khamene’i with regard to future Iranian foreign policy.

- Nevertheless, more moderate Iranian leaders and factions, such as President Hassan Rouhani and the still influential former President Ali Akbar Hashemi- Rafsanjani, argue that Iran should not have any “permanent enemies” and that a pragmatic foreign policy could result in easing of international sanctions and increased support for Iran’s views on the Middle East. These views have drawn support from Iran’s youth and intellectuals who argue that Iran should adopt a foreign policy that avoids isolation and achieves greater integration with the international community. In contrast to Khamene’i’s statements, Rouhani said on September 13, 2015 that the JCPOA is “a beginning for creating an atmosphere of friendship and co-operation with various countries.”7

- Some Iranian figures, including the elected president during 1997-2005 Mohammad Khatemi, are considered reformists. Reformists have tended to focus more on promoting domestic reform than for a dramatically altered foreign policy. However, most of Iran’s leading reformist figures have become sidelined without being able to achieve significant change either domestically or in foreign policy.

Instruments of Iranian Foreign Policy

Iran employs a number of different methods and mechanisms to implement its foreign policy, some of which involve supporting armed factions that engage in international acts of terrorism.

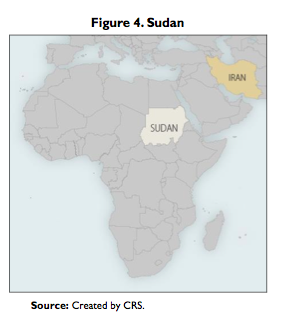

Financial and Military Support to Allied Regimes and Groups

As an instrument of its foreign policy, Iran provides arms, training, and military advisers in support of allied government as well as armed factions. Iran was placed on the U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism (“terrorism list”) in January 1984, and two of the governments Iran has supported – Syria and Sudan – are the two countries still on that list. Many of the groups Iran supports are named as foreign terrorist organizations (FTOs) by the United States.

The State Department report on international terrorism for 2014,8 released June 19, 2015, stated that in 2014 Iran “continued its terrorist-related activity, including for Palestinian terrorist groups in Gaza, Lebanese Hezbollah, and various groups in Iraq and throughout the Middle East.”

Iran’s operations in support of its allies—which generally includes arms shipments, provision of advisers, training, and funding—is carried out by the Qods (Jerusalem) Force of the IRGC (IRGC-QF). The IRGC-QF is headed by IRGC Maj. Gen. Qasem Soleimani, who is said to report directly to Khamene’i.9 Some IRGC-QF advisers have been reported to sometimes engage in direct combat, particularly in the Syrian civil conflict.

The range of armed factions that Iran supports are discussed in the regional sections below.

- Some Iranian-supported factions are opposition movements, while others are militia forces supporting governments that are allied to Iran. These governments include those of President Bashar Al Asad of Syria and Prime Minister Haydar Al Abbadi of Iraq.

- Some armed factions that Iran supports have not been named as FTOs and have no record of committing acts of international terrorism. Such groups include the Houthi (“Ansar Allah”) movement in Yemen (composed of Zaidi Shiite Muslims) and some underground Shiite opposition factions in Bahrain.

- Iran opposes—or declines to actively support—Islamist armed groups that work against Iran’s core interests. For example, Al Qaeda and the Islamic State organization are orthodox Sunni Muslim organizations that Iran apparently perceives as significant threats.10 Over the past few years, Iran has expelled some Al Qaeda activists who sought refuge there after the September 11, 2001, attacks against the United States. Iran is actively working against the Islamic State organization, which opposes Asad of Syria and the Abbadi government in Iraq.

- Iran does support some Sunni Muslim groups that further Tehran’s interests. Two Sunni Palestinian FTOs, Hamas and Palestine Islamic Jihad – Shiqaqi Faction, have received Iranian support in part because they are antagonists of Israel.

Other Political Action

- Iran’s foreign policy is not limited to militarily supporting allied governments and armed factions. A wide range of observers report that Iran has provided funding to political candidates in neighboring Iraq and Afghanistan in an effort to build political allies in those countries.11

- Iran has reportedly provided direct payments to leaders of neighboring states in an effort to gain and maintain their support. For example, in 2010 then-President of Afghanistan Hamid Karzai publicly acknowledged that his office had accepted direct cash payments from Iran. 12

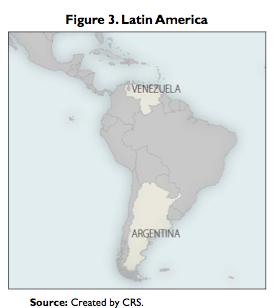

- Iran has established some training and education programs that bring young Muslims to study in Iran. One such program, headed by Iranian cleric Mohsen Rabbani, is focused on Latin America, even though the percentage of Muslims there is low.13

Diplomacy

At the same time that it funds and trains armed factions in the region, Iran also uses traditional diplomatic tools.

- Iran has an active Foreign Ministry and maintains embassies in almost all major countries with which it has formal diplomatic relations. Iran’s Supreme Leader Grand Ayatollah Ali Khamene’i rarely travels outside Iran, but Iran’s elected presidents, including the current President Hassan Rouhani travel frequently and not only within Iran’s immediate neighborhood.

- Iran actively participates in or seeks to join many different international organizations, including those that are dominated by members opposed to Iran’s ideology and/or critical of its domestic human rights practices. For example Iran has sought to join the U.S. and Europe-dominated World Trade Organization (WTO). It has also sought to join such regional organizations as the South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) that groups Central Asian states with Russia and China. Iran is an observer in the SCO and SCO officials say that implementation of the JCPOA could pave the way for Iran to obtain full membership in the body.14

- Iran participates actively in multilateral organizations that tend to support some aspects of Iranian ideology, such as its criticism of great power influence over developing states. From August 2012 until August 2015, Iran held the presidency of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), which has about 120 member states and 17 observer countries. Iran hosted a summit of the movement in August 2012, when it took over the rotating leadership.

- The JCPOA represented an attempt to ensure that Iran’s nuclear program is purely peaceful, demonstrating evident lack of international trust in Iran’s nuclear intentions. Iran is a party to all major nonproliferation conventions, including the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), and insists that it has adhered to all its commitments under these conventions.

- During 2003-2005, Iran negotiated limits on its nuclear program with three European Union countries—Britain, France and Germany (“EU-3”). In 2006, the negotiating powers expanded to include the United States and the two other Permanent Members of the U.N. Security Council, Russia and China, to form the “P5+1.” The P5+1 and Iran reached an interim nuclear agreement in November 2013 (“Joint Plan of Action,” or JPOA) and a framework of a comprehensive nuclear accord on April 2, 2015. The P5+1 and Iran set a deadline of June 30, 2015, to reach finalize an accord.

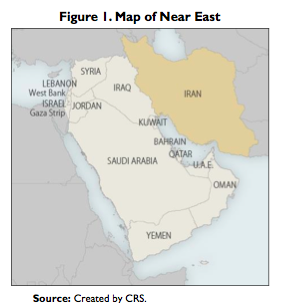

Near East Region

The overwhelming focus of Iranian foreign policy is on the Near East region, as demonstrated by Iran’s employment of all the various instruments of its foreign policy, including deployment of the IRGC-Qods Force in several locations in the region. All the various motivations of Iran’s foreign policy appear to be at work in its actions in the region, including its efforts to empower Shiite communities that fuel sectarian responses. Iranian steps to aid Shiites in Sunni-dominated countries often fuel responses by those governments, thus aggravating sectarian tensions.15

The Arab States of the Persian Gulf

Iran has a 1,100-mile coastline on the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman. The Persian Gulf monarchy states (Gulf Cooperation Council, GCC: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates) have always been a key focus of Iran’s foreign policy. These states, all controlled by Sunni- led governments, cooperate extensively with U.S. policy toward Iran, including by hosting significant numbers of U.S. forces at their military facilities and procuring U.S. military equipment, including missile defense technology. GCC facilities would be critical to any U.S. air operations against Iran in the event of a regional conflict, and GCC hosting of these facilities presumable serves as a deterrent to any direct Iranian aggression against the GCC countries.

Iran has a 1,100-mile coastline on the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman. The Persian Gulf monarchy states (Gulf Cooperation Council, GCC: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates) have always been a key focus of Iran’s foreign policy. These states, all controlled by Sunni- led governments, cooperate extensively with U.S. policy toward Iran, including by hosting significant numbers of U.S. forces at their military facilities and procuring U.S. military equipment, including missile defense technology. GCC facilities would be critical to any U.S. air operations against Iran in the event of a regional conflict, and GCC hosting of these facilities presumable serves as a deterrent to any direct Iranian aggression against the GCC countries.

At the same time, the GCC states generally do not try to openly antagonize Iran and, although all the GCC states enforce international sanctions against Iran, they also all maintain relatively normal trading relations with Iran.

The following sections analyze the main outlines of Iran’s policy toward each GCC state. Although Saudi Arabia’s positions are often taken to represent those of all GCC states toward Iran, there are some distinct differences within the GCC on Iran policy, as discussed below.

Saudi Arabia16

Iranian leaders assert that Saudi Arabia seeks hegemony for its brand of Sunni Islam and that Saudi Arabia is working with the United States to deny Shiite Muslim governments and factions influence in the region. Conversely, Saudi Arabia has used the claim of an Iranian quest for regional hegemony to justify military intervention in Bahrain in 2011 and in Yemen in 2015. Both countries have tended to exaggerate the influence of the other, leading to actions that have fueled the apparently expanding Sunni-Shiite conflict in the region. Some of the region’s conflicts are described as “proxy wars” between Saudi Arabia and Iran because each tends to back rival sides. The one exception might be Iraq, where both Iran and Saudi Arabia back the Shiite-dominated government, although Iran does so much more directly and substantially.

The Saudis also repeatedly cite past Iran-inspired actions as a reason for distrusting Iran; these actions include encouraging violent demonstrations at some Hajj pilgrimages in Mecca in the 1980s and 1990s, which caused a break in relations from 1987 to 1991. Some Saudis accuse Iran of supporting Shiite protesters and armed groups active in the Kingdom’s restive Shiite-populated Eastern Province. Saudi Arabia asserts that Iran instigated the June 1996 Khobar Towers bombing and accuses it of sheltering the alleged mastermind of the bombing, Ahmad Mughassil, purportedly a leader of Saudi Hezbollah. Mughassil was arrested in Beirut in August 2015, indicating that Iran might have expelled him if it was sheltering him. Saudi and Iranian have had occasional diplomatic discussions about their regional differences since President Rouhani came into office, but any rapprochement has been stalled recently over the Yemen issue, discussed below.

United Arab Emirates (UAE)17

Like Saudi Arabia, the UAE tends to take hardline positions on Iran. However, unlike Saudi Arabia, the UAE has a large population of Iranian expatriates in Dubai emirate, historically close business ties to Iran’s large trading companies, and territorial disputes with Iran over the Persian Gulf islands of Abu Musa and the Greater and Lesser Tunb islands. The Tunbs were seized by the Shah of Iran in 1971, and the Islamic Republic took full control of Abu Musa in 1992, appearing to violate a 1971 UAE-Iran agreement to share control of that island. The UAE has sought to refer the dispute to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), but Iran has insisted on resolving the issue bilaterally. (ICJ referral requires concurrence from both parties to a dispute.) In the aftermath of the 2013 interim nuclear agreement (JPOA), the two countries held direct discussions on the issue and reportedly made progress. Iran reportedly removed some military equipment from the islands.18 However, no progress has been announced since.

The UAE and Iran maintain relatively normal trade and diplomatic ties, and Iranian-origin residents of Dubai number about 300,000. In accordance with long-standing traditions, many Iranian-owned businesses are located in Dubai emirate (including branch offices of large trading companies based in Tehran and elsewhere in Iran). These relationships have often triggered U.S. concerns about the apparent re-exportation of some U.S. technology to Iran,19 although the UAE has said it has taken extensive steps, in cooperation with the United States, to reduce such leakage.

Qatar20

Qatar appears to occupy a “middle ground” between the anti-Iran animosity of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain, and the intensive high-level engagement with Iran exhibited by Oman. Qatar invariably joins GCC consensus statements on Iran, most of which criticize Iran’s regional policies. However, Qatar maintains consistent high level contact with Iran; the speaker of Iran’s Majles (parliament) visited Qatar in March 2015 and the Qatari government allowed him to meet with Hamas leaders who are in exile in Qatar. But, unlike Oman and Kuwait, Qatar has not exchanged leadership level visits with Iran. Despite its contacts with Iran, Qatar also has not hesitated to pursue policies that are opposed to Iran’s interests, for example by providing arms and funds to factions in Syria that are fighting to oust Syrian President Bashar Al Asad.

Unlike the UAE, Qatar does not have any active territorial disputes with Iran. Yet, Qatari officials reportedly remain wary that Iran could try to encroach on the large natural gas field it shares with Iran, fueled by occasional Iranian statements such as one in April 2004 by Iran’s deputy oil minister that Qatar is probably producing more gas than “her right share” from the field. He added that Iran “will not allow” its wealth to be used by others.

Bahrain21

Bahrain is a core member of the hardline camp within the GCC on Iran issues. Bahrain is about 60% Shiite-inhabited, many of whom are of Persian origin, but the government is dominated by the Sunni Muslim Al Khalifa family. In 1981 and again in 1996, Bahrain publicly claimed to have thwarted Iranian attempts to support efforts by Bahraini Shiite dissidents to violently overthrow the ruling Al Khalifa family. Bahrain has consistently accused Iran of supporting radical Shiite factions that are part of a broader and mostly peaceful uprising begun in 2011 by mostly Shiite demonstrators.22 The State Department report on international terrorism for 2013 stated that Iran has attempted to provide arms and other aid to Shiite militants in Bahrain. However, the State Department report for 2014, released June 19, 2015, did not specifically repeat that assertion.23 Some outside observers—including a government-appointed commission of international experts called the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry—have suggested that Iran’s support for the Shiite uprising has been minimal.24 On several earlier occasions, tensions had flared over Iranian attempts to question the legitimacy of a 1970 U.N.-run referendum in which Bahrainis opted for independence rather than for affiliation with Iran.

Kuwait25

Kuwait cooperates with U.S.-GCC efforts to contain Iranian power, but does not demonstrate enthusiasm for GCC military action or proxy warfare against Iran’s regional interests. Kuwait exchanges leadership-level visits with Iran; Kuwait’s Amir Sabah al-Ahmad Al Sabah visited Iran in June 2014, meeting not only with President Hassan Rouhani but also Supreme Leader Ali Khamene’i. Kuwait appears to view Iran as a helpful actor in stabilizing Iraq, which occupies a central place in Kuwait’s foreign policy because of the 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Kuwait cooperates extensively with the Shiite-dominated government in Baghdad despite Saudi and other GCC criticism of the government’s marginalizing Sunni Iraqis.

Kuwait is also differentiated from some of the other GCC states its relative confidence in the loyalty of its Shiite population. About 25% of Kuwaitis are Shiite Muslims, but Kuwait’s Shiites are extensively integrated into the political process and Kuwait’s economy, and have never constituted a restive, anti-government minority. Iran was unsuccessfully in supporting Shiite radical groups in Kuwait in the 1980s as a means to try to pressure Kuwait not to support the Iraqi war effort in the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988). At the same time, Kuwait has stood firm against alleged Iranian spying or covert action in Kuwait. On numerous occasions, and as recently as August 2015, Kuwait has announced arrests of Kuwaitis alleged to be spying for or working with the IRGC-QF or Iran’s intelligence service.

Oman26

Of the GCC states, the Sultanate of Oman is closest politically to Iran. Omani officials assert that engagement with Iran is a more effective means to moderate Iran’s foreign policy than to threaten it or undertake indirect action against Iran through proxies. Oman also remains grateful for the Shah’s sending of troops to help the Sultan suppress rebellion in the Dhofar region in the 1970s, even though Iran’s regime changed since then.27 Sultan Qaboos made a state visit to Iran in August 2009, even though the visit coincide with large protests against alleged fraud in the reelection of then-President Mahmud Ahmadinejad. Qaboos visited again in August 2013, reportedly to explore concepts for improved U.S.-Iran relations and to facilitate U.S.-Iran talks that led to the JPA and its banks serve as a financial channel for the permitted transfer of hard currency oil sales proceeds to Iran under the JPA.28It subsequently hosted P5+1 – Iran nuclear negotiations that led to the JCPOA. In March 2014, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani visited Oman, the only GCC state he has visited since taking office.

Omani ties to Iran manifest in several ways. Unlike Saudi Arabia and some other GCC states, Oman reportedly has not materially supported any factions fighting against the Asad regime in Syria. Nor did Oman join the Saudi-led Arab intervention against the rebel Zaidi Shiite Houthi movement in Yemen that began in March 2014. Oman’s relationship with Iran and its membership in the GCC alliance as enabled Oman to undertake the role of mediator in both of those conflicts.

Iranian Policy in Iraq and Syria: Islamic State Crisis29

Iran’s policy has been to support the Shiite-led government in Iraq and the Alawite-led, pro- Iranian government in Syria. That policy has come under strong challenge from the Islamic State organization, which threatens the Iraqi government as well as that of Iran’s close ally President Bashar Al Asad. The United States and Iran have worked in parallel, although separately, to assist the Iraqi government against the Islamic State organization. However, the United States and Iran hold opposing positions on the Asad regime.

Iraq30

In Iraq, the U.S. military ousting of Saddam Hussein in 2003 benefitted Iran strategically by removing a long-time antagonist and producing governments led by Shiite Islamists who have long-standing ties to Iran. Iran was a strong backer of the government of Prime Minister Nuri al- Maliki, a Shiite Islamist who Tehran reportedly viewed as loyal and pliable. Maliki supported most of Iran’s regional goals, for example by allowing Iran to overfly Iraqi airspace to supply the Asad regime.31 The June 2014 offensive led by the Islamic State organization threatened Iraq’s government and at one point brought Islamic State forces to within 50 miles of the Iranian border. Iran responded quickly by supplying the Baghdad government as well as the peshmerga force of the autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) with IRGC-QF advisers, intelligence drone surveillance, weapons shipments, and other direct military assistance.32

Iranian leaders also acquiesced to U.S. insistence that Iran’s longtime ally Maliki be replaced, and Tehran concurred with his replacement by the more inclusive Abbadi.33 U.S. officials, including Secretary of State John Kerry, have said that Iran’s targeting of the Islamic State generally contributes positively to U.S. efforts to assist the Iraqi government.

Still, many aspects of Iranian policy in Iraq reportedly trouble U.S. policymakers. Iran helped establish many of the Shiite militias that fought the United States during 2003-2011. During 2011-2014, the Shiite militia evolved into political organizations, but Iran has helped reactivate and empower some of them to support the Iraq Security Forces (ISF) against the Islamic State. The militias that Iran works most closely with in Iraq include As’aib Ahl Al Haq (League of the Righteous), Kata’ib Hezbollah (Hezbollah Brigades), and the Badr Organization. The Mahdi Army of Moqtada Al Sadr (renamed the Peace Brigades in 2014) was supported extensively by Iran during the 2003-2011 U.S. intervention in Iraq but has sought to distance itself from Iran in the more recent campaigns against the Islamic State. Kata’ib Hezbollah is designated a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) by the United States. The participation of some Shiite militias has increased tensions with some of Iraq’s Sunnis because some of these militia fighters have carried out reprisals against Sunnis after recapturing Sunni-inhabited territory from the Islamic State.

In late 2014, news reports citing Iranian elite figures, reported that Iran had spent more than $1 billion in military aid to Iraq in the approximately six months after the June 2014 Islamic State offensive.34 That figure presumably also includes weapons transferred to the Shiite militias as well as the ISF. CRS has no way to independently confirm any of the estimates on Iranian aid to Iraqi forces.

Syria35

On Syria, the United States has stated that President Bashar Al Asad should eventually leave office as part of a negotiated political solution to the conflict. Iran’s policy has apparently been to try to keep Asad in power because he has been Iran’s closest Arab ally and because Syria is the main transit point for Iranian weapons shipments to Hezbollah. Both Iran and Syria have used Hezbollah as leverage against Israel to try to achieve regional and territorial aims. Iran also asserts that Asad is a bulwark against the takeover of Syria by the Islamic State.

U.S. officials and reports assert that Iran is providing substantial amounts of material support to the Syrian regime, including funds, weapons, IRGC-QF advisors, and recruitment of Hezbollah and other non-Syrian Shiite militia fighters.36 Some experts say the Iranian direct intervention has, at least at times, gone beyond QF personnel to include an unknown number of IRGC ground forces as well.37 In June 2015, the office of the U.N. Special Envoy to Syria Staffan de Mistura stated that the envoy estimates Iran’s aid to Syria, including military and economic aid, to total about $6 billion per year.38 Other estimates vary, and CRS has no way to independently corroborate any particular estimate.

At the same time, some experts assess that Iran might be willing to abandon Asad, as it abandoned Maliki in Iraq, if Iran’s interests in Syria could be secured.39 In December 2012, and again in July 2015, Iran announced proposals for a peaceful transition in Syria that would culminate in free, multiparty elections. However, President Rouhani and other Iranian leaders continued to assert that any political negotiations be preceded by a cessation of hostilities – an assertion that cast doubt on whether Iran is willing to accept Asad’s eventual departure.

Israel: Iran’s Support for Hamas and Hezbollah40

Iran opposes Israel as what it asserts is an illegitimate creation of the West and an oppressor of the Palestinian people and other Arab Muslims. The position of Iran’s current regime differs dramatically from that of the pre-1979 regime of the Shah of Iran. Israel and the Shah’s regime had relatively normal relations, including embassies in each other’s capitals and an extensive network of economic ties.

Supreme Leader Khamene’i has repeatedly called Israel a “cancerous tumor” that should be removed from the region. In a September 2015 speech, Khamene’i stated that Israel will likely not exist in 25 years – the time frame for the last of the specific JCPOA restrictions on Iran’s nuclear program to expire. 41 Iran’s open hostility to Israel—manifested in part by its support for groups that undertake armed action against Israel—fuels assertions by Israeli leaders that a nuclear armed Iran would constitute an “existential threat” to the State of Israel. Iran’s support for armed factions on Israel’s borders could represent an Iranian attempt to acquire leverage over Israel. More broadly, Iran might be attempting to disrupt prosperity, morale, and perceptions of security among Israel’s population in a way that undermines the country’s appeal to those who have options to live elsewhere. The formal position of the Iranian Foreign Ministry is that Iran would not seek to block an Israeli-Palestinian settlement but that the process is too weighted toward Israel to yield a fair result.

Iran’s leaders routinely state that Israel presents a serious threat to Iran and that the international community applies a “double standard” to Iran as compared to Israel’s presumed nuclear arsenal. Iranian diplomats point out in international meetings that, despite apparently being the only Middle Eastern country to possess nuclear weapons and not being a party to the Nuclear Non- Proliferation Treaty, Israel does not face internationally imposed penalties as a consequence. In identifying Israel as a threat, Iran’s leaders cite Israeli official statements that Israel retains the option to unilaterally strike Iran’s nuclear facilities. Iran also asserts that Israel’s purported nuclear arsenal is a main obstacle to achieving support for a weapons-of-mass-destruction (WMD) free zone in the Middle East.

Iran’s material support for militant anti-Israel groups has long concerned U.S. Administrations. For at least a decade, the annual State Department report on international terrorism has repeated its claim that Iran provides funding, weapons, and training to Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad— Shiqaqi Faction (PIJ), the Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades (a militant offshoot of the dominant Palestinian faction Fatah), and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC). All are named as foreign terrorist organizations (FTOs) by the State Department. Iran has long supported Lebanese Hezbollah, which is an FTO and which portrays itself as the vanguard of resistance to Israel. In November 2014, a senior IRGC commander said that Iran had provided Hezbollah and Hamas with training and Fateh-class missiles, which enable the groups to attack targets in Israel.42

Hamas43

The annual State Department report on terrorism has consistently stated that Iran gives Hamas funds, weapons, and training. Hamas seized control of the Gaza Strip in 2007 and now administers that territory. Although it formally ceded authority over Gaza in June 2014 to a consensus Palestinian Authority government, Hamas retains de-facto security control over that territory. Its terrorist attacks using operatives within Israel have significantly diminished in number since 2005, but Hamas continues to occasionally engage in armed action against Israel, using rockets and other weaponry supplied by Iran. Israel and Hamas came into conflict in late 2008-early 2009; in November 2012; and during July and August, 2014.

The Iran-Hamas relationship was forged in the 1990s as part of an apparent attempt to disrupt the Israeli-Palestinian peace process through Hamas’s suicide bombings and other attacks on buses, restaurants, and other civilian targets inside Israel. However, Hamas’s position on the ongoing Syria conflict caused the Iran-Hamas relationship to falter. Largely out of sectarian sympathy with the mostly Sunni protesters and rebels in Syria, Hamas opposed the efforts by Asad, backed by Iran, to defeat the rebellion militarily. The rift apparently contributed to a lessening of Iran’s support to Hamas in its 2014 conflict with Israel as compared to previous Hamas-Israel conflicts in which Iran backed Hamas extensively. Since the latest Hamas-Israel conflict, Iran has apparently sought to rebuild the relationship with Hamas by providing missile technology that Hamas used to construct its own rockets and by helping it rebuild tunnels destroyed in the conflict with Israel.44 Some Hamas leaders have reportedly welcomed rebuilding the group’s relations with Iran, perhaps because of financial difficulties the organization has faced since the military leadership in Egypt began closing smuggling tunnels at the Gaza-Sinai border in 2013. According to some estimates, Iran’s financial support (not including weapons provided) has ranged from about $300 million per year during periods of substantial Iran-Hamas collaboration, to much smaller amounts during periods of tension between the two, such as those discussed above.45 CRS has no way to corroborate the levels of Iranian funding to Hamas.

Hezbollah46

Lebanese Hezbollah, which Iranian leaders assert is an outgrowth of the 1979 Iranian revolution itself, is arguably Iran’s most significant ally in the region. Hezbollah has acted in support of its own as well as Iranian interests on numerous occasions and in many forms, including through acts of terrorism and other armed action. The Iran-Hezbollah relationship began when Lebanese Shiite clerics of the pro-Iranian Lebanese Da’wa (Islamic Call) Party began to organize in 1982 into what later was unveiled in 1985 as Hezbollah. As Hezbollah was forming, the IRGC sent advisory forces to help develop Hezbollah’s military wing, and these IRGC forces subsequently became the core of what is now the IRGC-QF.47

The 2014 U.S. intelligence community worldwide threat assessment stated that Hezbollah “has increased its global terrorist activity in recent years to a level that we have not seen since the 1990s,” but the 2015 worldwide threat assessment, delivered in February 2015, did not repeat that assertion. In part as a consequence of its military strength, Hezbollah now plays a major role in decision-making and leadership selections in Lebanon. The Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) rarely acts against Hezbollah’s forces or interests. However, there has been vocal criticism of Hezbollah within and outside Lebanon for its active supports for its other key patron, Asad, against the Sunni-led rebellion in Syria. That involvement, reportedly urged and assisted by Iran, has diluted Hezbollah’s image as a steadfast opponent of Israel by embroiling it in a war against fellow Muslims.

Iran’s political, financial, and military aid to Hezbollah has helped it become a major force in Lebanon’s politics. The 2010 congressionally-mandated Department of Defense report on Iran’s military power asserts Iranian aid levels to Hezbollah are “roughly $100 – $200 million per year.”48 That estimate is consistent with figures cited in past years’ State Department reports on international terrorism. Still, CRS has no way to independently corroborate any such estimates.

Earlier, Hezbollah’s attacks on Israeli forces in southern Lebanon contributed to an Israeli withdrawal in May 2000, and Hezbollah subsequently maintained military forces along the border. Hezbollah fired Iranian-supplied rockets on Israel’s northern towns during a July–August 2006 war with Israel, including at the Israeli city of Haifa (30 miles from the border)49 and in July 2006 hit an Israeli warship with a C-802 sea-skimming missile. Iran bought the C-802 from China in the 1990s and almost certainly was the supplier of the weapon to Hezbollah. Hezbollah was perceived in the Arab world as a victor in the war for holding out against Israel. Since that conflict, Iran has resupplied Hezbollah to the point where it has, according to Israeli sources, as many as 100,000 rockets and missiles, some capable of reaching Tel Aviv from south Lebanon, as well as upgraded artillery, anti-ship, anti-tank, and anti-aircraft capabilities.50

In the context of the conflict in Syria, Israel has carried out occasional air strikes inside Syria against Hezbollah commanders and purported arms shipments via Syria to Hezbollah. In January 2015, Hezbollah attacked an Israeli military convoy near the Lebanon-Israel-Syria tri-border area, killing two Israeli soldiers and making it the deadliest Hezbollah attack on Israeli territory since 2006. However, these incidents have not, to date, escalated into a broader Israel-Hezbollah conflict.

Yemen51

Yemen does not appear to represent a core security interest of Iran, but Iranian leaders appear to perceive Yemen’s instability as an opportunity to acquire additional leverage against Saudi Arabia and the GCC states, several of which border Yemen. Yemen’s elected leaders have long claimed that Iran is trying to take advantage of Yemen’s instability by supporting Shiite rebels in Yemen— a Zaydi Shiite revivalist movement known as the “Houthis”—with arms and other aid. Yemen has been unstable since the 2011 “Arab Spring” uprisings, which included Yemen and which forced longtime President Ali Abdullah Saleh to resign in January 2012. In September 2014, the Houthis and their allies seized key locations in the capital, Sana’a, and took control of major government locations in January 2015, forcing Saleh’s successor, Abd Rabu Mansur Al Hadi, to flee to Aden. The Houthis and their allies subsequently advanced on Aden, prompting Saudi Arabia to assemble a ten-country Arab coalition, with logistical help from the United States, to undertake military action to stop the Houthi advance.52 Saudi officials have explained their military action, which has escalated in mid-2015 to include some ground forces, as an effort to restore the elected government and, as a by-product, to stop Iran from expanding its influence in the region.

There is debate over the extent to which the Houthi advance is a priority of Iranian policy. Iran has not denied aiding the Houthis, but has sought to minimize its involvement in Yemen. A senior Iranian official reportedly told journalists in December 2014 that the Qods Force has a “few hundred” personnel in Yemen training Houthi fighters.53 Iran reportedly has shipped unknown quantities of arms to the Houthis, as has been reported by a panel of U.N. experts assigned to monitor Iran’s compliance with U.N. restrictions on its sales of arms abroad. Nonetheless, Iran’s aid to the Houthis appears less systematic or large-scale than is Iran’s support to the government of Iraq or to Asad of Syria. Observers describe Iran’s influence over the Houthis as limited and assert that the Houthi military action against President Hadi was not instigated by Iran. On April 20, 2015, National Security Council spokesperson Bernadette Meehan told reporters that, “It remains our assessment that Iran does not exert command and control over the Houthis in Yemen,” and an unnamed U.S. intelligence official reportedly said, “It is wrong to think of the Houthis as a proxy force for Iran.”54 No firm estimates of Iranian aid to the Houthis exists, but some Houthi sources estimate Iran has supplied the group with “tens of millions of dollars” total over the past few years.55

Iran might have increased its aid to the Houthis as a counter to the Saudi military campaign, which began in April 2015, against the Houthi advance. Iran appears to be seeking to frustrate Saudi foreign policy.56 The United States augmented its naval presence off the coast of Yemen with an aircraft carrier in mid-April 2015, in part to try to prevent any additional Iranian weapons shipments to Iran. The Iranian ship convoy turned around rather than confront the U.S. Navy, and the U.S. presence appears to have deterred further Iranian efforts to arm the Houthis by ship.

Turkey57

Iran shares a short border with Turkey, but the two have extensive political and economic relations. Turkey is a member of NATO, and Iran has sought to limit Turkey’s cooperation with its NATO partners in any U.S.-backed efforts to emplace even defensive equipment, such as missile defense technology, near Iran’s borders. Iran is a major supplier of both oil and natural gas to Turkey, through a joint pipeline that began operations in the late 1990s and has since been supplemented by an additional line. Iran and Turkey also agreed in 2011 to cooperate to try to halt cross border attacks by Kurdish groups that oppose the governments of Turkey (Kurdistan Workers’ Party, PKK) and of Iran (Free Life Party, PJAK), and which enjoy a measure of safe have in northern Iraq. Turkey has also been supportive of P5+1 – Iran negotiations and the JCPOA, apparently in the expectation that the agreement not only would constrain Iran’s nuclear program but also that the lifting of sanctions on Iran would remove constraints on Iran-Turkey trade.

On the other hand, the two countries have disputes on some regional issues, possibly caused by the sectarian differences between Sunni-inhabited Turkey and Shiite Iran. Turkey has been a key advocate of Syrian President Asad leaving office as part of a possible solution for conflict-torn Syria. Iran, as has been noted, is a key supporter of Asad.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, Iran and Turkey were at odds over the strategic engagement of Turkey’s then leaders with Israel. The Iran – Turkey dissonance on the issue has faded since the Islamist-rooted Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power in Turkey about a decade ago. Since then Turkey has realigned its foreign policy somewhat and has been a significant supporter of Hamas, which also enjoys Iran’s support, and other Islamist movements.

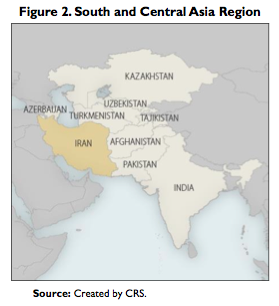

South and Central Asia Region

Iran’s relations with countries in the Caucasus, Central Asia, and South Asia vary significantly, from close relations with Afghanistan to animosity with Azerbaijan. Regardless of any differences, most countries in these regions conduct relatively normal trade and diplomacy with Iran. Some countries in these regions, such as Uzbekistan and Pakistan, face significant domestic threats from radical Sunni Islamist extremist movements similar to those that Iran characterizes as a threat to regional stability. Such common interests create an additional basis for Central and South Asian cooperation with Iran.

Iran’s relations with countries in the Caucasus, Central Asia, and South Asia vary significantly, from close relations with Afghanistan to animosity with Azerbaijan. Regardless of any differences, most countries in these regions conduct relatively normal trade and diplomacy with Iran. Some countries in these regions, such as Uzbekistan and Pakistan, face significant domestic threats from radical Sunni Islamist extremist movements similar to those that Iran characterizes as a threat to regional stability. Such common interests create an additional basis for Central and South Asian cooperation with Iran.

Most of the countries in Central Asia are relatively stable and are governed by authoritarian leaders, offering Iran little opportunity to exert influence by supporting opposition factions. Still, unrest does flare occasionally, including in mid-2015 in Tajikistan, which has never fully resolved a significant civil war in the years after the breakup of the Soviet Union. Afghanistan, by contrast, is a weak state supported by international forces, and Iran has substantial influence over several major factions and regions of the country. Some countries in the region, particularly India, apparently seek greater integration with the United States and other world powers and have sought to limit or downplay cooperation with Iran and to comply with sanctions against Iran. The following sections cover those countries in the Caucasus and South and Central Asia that have significant economic and political relationships with Iran.

The South Caucasus: Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan is, like Iran, mostly Shiite Muslim-inhabited. However, Azerbaijan is ethnically Turkic and its leadership is secular; moreover, Iran and Azerbaijan have territorial differences over boundaries in the Caspian Sea. Iran also asserts that Azeri nationalist movements might stoke separatism among Iran’s large Azeri Turkic population, which has sometimes been restive. In July 2001, Iranian warships and combat aircraft threatened a BP ship on contract to Azerbaijan out of an area of the Caspian that Iran claims as its territorial waters. The United States called the incident inconsistent with diplomatic processes under way to determine Caspian boundaries,58 among which are negotiations that regional officials say might resolve the issue at a planned 2016 regional summit meeting in Astana, Kazakhstan. Largely as a result of these differences, Iran has generally tilted toward Armenia, which is Christian, in Armenia’s disputes with Azerbaijan. In this context, Azerbaijan has entered into substantial strategic cooperation with the United States, directed not only against Iran but also against Russia. The U.S.-Azerbaijan cooperation has extended to Azerbaijan’s deployments of troops to and facilitation of supply routes to Afghanistan,59 as well as counter-terrorism cooperation.

Azerbaijan has been a key component of U.S. efforts to structure oil and gas routes in the region to bypass Iran. In the 1990s, the United States successfully backed construction of the Baku- Tblisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline, intended in part to provide non-Iranian and non-Russian export routes. On the other hand, the United States has apparently accepted Azerbaijan’s assertions that it needs to deal with Iran on some major regional energy projects. Several U.S. sanctions laws have exempted from sanctions long-standing joint natural gas projects that involve some Iranian firms—particularly the Shah Deniz natural gas field and pipeline in the Caspian Sea. The project is run by a consortium in which Iran’s Naftiran Intertrade Company (NICO) holds a passive 10% share. (The other significant partners are BP, Azerbaijan’s national energy firm SOCAR, and Russia’s Lukoil.) 60

Central Asia

Iran has generally sought positive relations with the leaderships of the Central Asian states, even though most of these leaderships are secular. All of the Central Asian states are inhabited in the majority by Sunnis, and several have active Sunni Islamist opposition movements. The Central Asian states have long been wary that Iran might try to promote Islamic movements in Central Asia, but more recently the Central Asian leaders have seen Iran as an ally against the Sunni movements that are active in Central Asia, such as the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU).61 That group, which is active in Afghanistan, in mid-2015, declared its loyalty to the Islamic State organization. The Islamic State has recruited fighters from Central Asia to help fill its combat ranks in Iraq and Syria,62 and Central Asian leaders express concern that these fighters could return to their countries of origin to conduct terrorist attacks against the Central Asian governments. Almost all of the Central Asian states share a common language and culture with Turkey; Tajikistan is alone among them in sharing a language with Iran.

Iran and the Central Asian states carry on normal economic relations. In December 2014, a new railway was inaugurated through Iran, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan, providing a link from the Persian Gulf to Central Asia.63

Along with India and Pakistan, Iran has been given observer status in a Central Asian security grouping called the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO—Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan). In April 2008, Iran applied for full membership in the organization. Apparently in an effort to cooperate with international efforts to pressure Iran, in June 2010, the SCO barred admission to Iran on the grounds that it is under U.N. Security Council sanctions.64 However, SCO officials have stated that the finalization of the JCPOA might remove existing obstacles to Iran’s full membership in the body.

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan and Iran have a land border in Iran’s northeast. Iran’s Supreme Leader, Grand Ayatollah Ali Khamene’i, is of Turkic origin; his family has close ties to the Iranian city of Mashhad, capital of Khorasan Province, which borders Turkmenistan. The two countries are also both rich in natural gas reserves. A natural gas pipeline from Iran to Turkey, fed with Turkmenistan’s gas, began operations in 1997, and a second pipeline was completed in 2010. Turkmenistan still exports some natural gas through the Iran-Turkey gas pipeline, even though China has since become Turkmenistan’s largest natural gas customer. Perhaps in an attempt to diversify gas export routes, Niyazov’s successor, President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov, signaled in 2007 that Turkmenistan sought to develop a trans-Caspian gas pipeline. That project has not proceeded, to date.

Another potential project favored by Turkmenistan and the United States would likely reduce interest in pipelines that transit Iran. President Berdymukhamedov has revived Niyazov’s 1996 proposal to build a gas pipeline through Afghanistan to Pakistan and India (termed the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India, or “TAPI” pipeline). Some preliminary memoranda of understanding among the leaders of the nations involved have been signed. U.S. officials have expressed strong support for the project as “a very positive step forward and sort of a key example of what we’re seeking with our New Silk Road Initiative, which aims at regional integration to lift all boats and create prosperity across the region.”65 However, doubts remain that the pipeline will actually be constructed.

Tajikistan

Iran and Tajikistan share a common Persian language, as well as literary and cultural ties. Despite the similar ethnicity, the two do not share a border and the population of Tajikistan is mostly Sunni, not Shiite. In March 2013, President Imamali Rakhmonov warned that since Tajikistan had become independent, the country and the world have experienced increased dangers from “arms races, international terrorism, political extremism, fundamentalism, separatism, drug trafficking, transnational organized crime, [and] the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.” These are threats that Iranian leaders claim to share. Rakhmonov also stated that close ties with neighboring and regional states were a priority, to be based on “friendship, good-neighborliness, [and] non- interference in each other’s internal affairs,” and to involve the peaceful settlement of disputes, such as over border, water, and energy issues.66 He stated that relations with Iran would be expanded. Tajikistan is largely dependent on its energy rich neighbors and has not announced any significant energy-related projects with Iran.

Some Sunni Islamist extremist groups that pose a threat to Tajikistan are allied with Sunni extremist groups, such as Al Qaeda, that Iranian leaders have publicly identified as threats to Iran and to the broader Islamic world.

Tajikistan’s leaders appear particularly concerned about Islamist movements in part because the Islamist-led United Tajik Opposition posed a serious threat to the newly independent government in the early 1990s, and a settlement of the insurgency in the late 1990s did not fully resolve government-opposition tensions. The Tajikistan government has detained members of Jundallah (Warriors of Allah)—a Pakistan-based Islamic extremist group that has conducted bombings and attacks against Iranian security personnel and mosques in Sunni areas of eastern Iran. In part because the group attacked some civilian targets in Iran, in November 2010, the State Department named the group an FTO—an action praised by Iran. In July 2013, Tajik police detained alleged operatives of the IMU, which is active in Uzbekistan and which also operates in Afghanistan.

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, apparently among the most stable of the Central Asian states, has appeared eager for an Iran nuclear deal that would lift sanctions on Iran. In early 2013, Kazakhstan hosted a round of the P5+1-Iran negotiations. In September 2014, Kazakhstan’s President Nursultan Nazarbayev held talks with President Rouhani. In his welcoming speech, Nazarbayev appeared to link progress in Iran-Kazakhstan relations to a comprehensive agreement with the international community on Iran’s nuclear program, saying: “Kazakhstan views Iran as an important partner in the world and a good neighbor in the Caspian region. We are confident that you will achieve successful solution on the biggest challenge in Iran—the nuclear program. It will influence the development of the Iranian economy and our relations.”67 The bilateral meeting reportedly included a broad agenda, including oil and gas, agriculture, and infrastructure issues.

The JCPOA potentially opens Iran to additional opportunities to cooperate with Kazakhstan on energy projects. Kazakhstan is an important power in Central Asia by virtue of its geographic location, large territory, ample natural resources, and economic growth. Kazakhstan possesses 30 billion barrels of proven oil reserves (about 2% of world reserves) and 45.7 trillion cubic feet of proven gas reserves (less than 1% of world reserves). There are five major onshore oil fields— Tengiz, Karachaganak, Aktobe, Mangistau, and Uzen—which account for about half of the proven reserves. Two major offshore oil fields in Kazakhstan’s sector of the Caspian Sea— Kashagan and Kurmangazy—are estimated to contain at least 14 billion barrels of recoverable reserves. Iran and Kazakhstan do not have any joint energy ventures in the Caspian or elsewhere, but in the aftermath of the JCPOA, the two countries reportedly agreed in principle to resume Caspian oil swap arrangements that were discontinued in 2011.68

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan and Iran do not share a common border, or significant language or cultural links. Since its independence in 1991, Uzbekistan, which has the largest military of the Central Asian states, has tended to see Iran as a potential regional rival and as a supporter of Islamist movements in the region. Over the past two years, Uzbekistan and Iran have moved somewhat closer together over shared stated concerns about Sunni Islamist extremist movements such as the Islamic State and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), which has declared allegiance to the Islamic State. The IMU, which has a reported presence in northern Afghanistan, has not claimed responsibility for any terrorist attacks in Iran and appears focused primarily on activities against the governments of Afghanistan and Uzbekistan.

Uzbekistan’s intense focus on the IMU began in February 1999 when, according to various reports, six bomb blasts in Tashkent’s governmental area killed more than 20 people. Uzbekistan’s President Islam Karimov had been expected to attend a high-level meeting in that area when the bombings took place, and the act was widely viewed as an effort to decapitate the Uzbek government. The government alleged that an exiled opposition figure led the plot, assisted by Afghanistan’s Taliban and IMU co-leaders Tahir Yuldashev and Juma Namangani. The Taliban were, at that time, in power in Afghanistan and granting safe haven to Osama bin Laden and other Al Qaeda leaders. In September 2000, the State Department designated the IMU as an FTO, stating that the IMU resorts to terrorism in pursuit of its main goal of toppling the government in Uzbekistan, including taking foreign hostages.69 During U.S.-led major combat operations in Afghanistan during 2001-2003, IMU forces assisted the Taliban and Al Qaeda, and IMU co-head Namangani was probably killed at that time.70

Uzbekistan has substantial natural gas resources but the two countries do not have joint energy- related ventures. Most of Uzbekistan’s natural gas production is for domestic consumption.

South Asia

The countries in South Asia face an even greater degree of threat from Sunni Islamic extremist groups than do the countries of Central Asia, and on that basis share significant common interests with Iran. The governments in South Asia are elected governments and thus tend to be more constrained by domestic laws and customs in their efforts to defeat extremist groups than are the Central Asian states. Iran apparently also has looked to some countries in South Asia as potential allies to help parry U.S. and European economic pressure. This section focuses on several countries in South Asia that have substantial interaction with Iran.

Afghanistan

In Afghanistan, Iran is apparently pursuing a multi-track strategy by helping develop Afghanistan economically, engaging the central government, and supporting pro-Iranian groups and anti-U.S. militants. A long-term Iranian goal appears to be to restore some of its traditional sway in eastern, central, and northern Afghanistan, where “Dari”-speaking (Dari is akin to Persian) supporters of the “Northern Alliance” grouping of non-Pashtun Afghan minorities predominate. Iran has also sought to use its influence in Afghanistan to try to blunt the effects of international sanctions against Iran.71 The two countries are said to be cooperating effectively in their shared struggle against narcotics trafficking from Afghanistan into Iran; Iranian border forces take consistent heavy losses in operations to try to prevent this trafficking.

Iran has sought influence in Afghanistan in part by supporting the Afghan government. President Hamid Karzai was replaced in September 2014 by Ashraf Ghani: both are Sunni Muslims and ethnic Pashtuns. In October 2010, Karzai admitted that Iran was providing cash payments (about $2 million per year) to his government, through his chief of staff.72 Iran’s close ally, Dr. Abdullah Abdullah, a Persian-speaking Afghan who is partly of Tajik origin, is “Chief Executive Officer” of the Afghan government under a power-sharing arrangement that resolved a dispute over the most recent election. It is not known whether these payments have continued since Ghani and Abdullah took office in September 2014.

Reflecting apparent concern about the U.S. military presence in Afghanistan, Iran reportedly tried to derail the Bilateral Security Agreement (BSA) that Ghani’s government signed on September 30, 2014. The BSA allows the United States to maintain troops in Afghanistan after 2014 but prohibits the United States from using Afghanistan as a base from which to launch military action against other countries. The two countries appear to have overcome differences over the BSA; President Ghani visited Tehran during April 19-20, 2015, and held discussions with Iranian leaders that reportedly focused on ways the two governments could cooperate against the Islamic State organization, which has developed affiliates inside Afghanistan.73

Even though it engages the Afghan government, Tehran has in the recent past sought leverage against U.S. forces in Afghanistan that are supporting that government. Past State Department reports on international terrorism have accused Iran of providing materiel support, including 107mm rockets, to select Taliban and other militants in Afghanistan, and of training Taliban fighters in small unit tactics, small arms use, explosives, and indirect weapons fire.74 The State Department terrorism reports also assert that Iran has supplied militants in Qandahar, which is a Pashtun-inhabited province in southern Afghanistan and which would indicate that Iran is not limiting its assistance to militants near its borders. The support Iran provides to Afghan insurgents gives Iran potential leverage in any Taliban-government political settlement in Afghanistan. In July 2012, Iran reportedly allowed the Taliban to open an office in Zahedan, in eastern Iran.75

Pakistan76

Relations between Iran and Pakistan have fluctuated over the past several decades. Pakistan supported Iran in the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq War, and Iran and Pakistan engaged in substantial military cooperation in the early 1990s. It has been widely reported that the founder of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program, A.Q. Khan, sold nuclear technology and designs to Iran.77

However, several factors divide the two countries. During the 1990s, Pakistan supported the Taliban in Afghanistan, whereas Iran supported the Persian-speaking and Shiite Muslim minorities there. The Taliban allegedly committed atrocities against Shiite Afghans (Hazara tribes) while seizing control of Persian-speaking areas of western and northern Afghanistan. Taliban fighters killed nine Iranian diplomats at Iran’s consulate in Mazar-e-Sharif in August 1998, prompting Iran to mobilize ground forces to the Afghan border. Afghan Taliban factions have a measure of safe-haven in Pakistan, and Iran reportedly is concerned that Pakistan might still harbor the ambition of returning the Taliban to power in Afghanistan.78 In addition, two Iranian Sunni Muslim militant opposition groups – Jundullah (named by the United States as an FTO, as discussed above) and Jaysh al-Adl – operate from western Pakistan. These groups have conducted a number of attacks on Iranian regime targets.

An additional factor distancing Iran and Pakistan is that Pakistan has always had strategic relations with Iran’s strategic adversary, Saudi Arabia. In March 2015, Saudi Arabia requested Pakistan’s participation in a Saudi-led coalition to try to turn back the advance in Yemen by the Iranian-backed Houthis (see above). Pakistan’s government is abiding by an April 2015 vote of its parliament not to enter the conflict, on the grounds that Pakistan could become embroiled in conflict far from its borders. The decisions has complicated Pakistan’s relations with the GCC states but was applauded by Iran.79 Experts also have long speculated that if Saudi Arabia sought to counter Iran’s nuclear program with one of its own, the prime source of technology for the Saudi program would be Pakistan.

Despite these differences, Iran and Pakistan conduct low-level military cooperation, including joint naval exercises in April 2014. The two nations’ bilateral agenda has increasingly focused on completing a major gas pipeline project that would link the two countries. Pakistan asserts that the Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline could help alleviate Pakistan’s energy shortages, while the project would provide Iran an additional customer for its large natural gas reserves. Then-president of Iran Ahmadinejad and Pakistan’s then-President Asif Ali Zardari formally inaugurated the project in March 2013. Iran has completed the line on its side of the border, but Pakistan has had persistent trouble financing the project on its side of the border. That roadblock might have been cleared by an agreement by China, reported on April 9, 2015, to build the pipeline at a cost of about $2 billion.80 Prior to the JCPOA, the United States opposed the project as providing a benefit to Iran’s energy sector and U.S. officials stated that the project could be subject to U.S. sanctions under the Iran Sanctions Act.81 However, the applicable provisions of the Iran Sanctions Act are to be waived as a consequence of the JCPOA, removing perhaps the last key obstacle to the project’s completion. As originally conceived, the line would continue on to India, but India has withdrawn from the project.

India82

India and Iran have overlapping histories, civilizations, and interests, aligning on numerous issues; for example, both countries have strongly supported minority factions based in the north and west of Afghanistan. India also is home to tens of millions of Shiite Muslims. As U.S. and international sanctions on Iran increased in 2010-2012, India sought to preserve its long-standing ties with Iran while still cooperating with U.S. and international sanctions on Iran. In 2010, India’s central bank ceased using a Tehran-based regional body, the Asian Clearing Union, to handle transactions with Iran. In January 2012, Iran agreed to accept India’s local currency, the rupee, to settle nearly half of its sales to India; that rupee account funds the sale to Iran of Indian wheat, pharmaceuticals, rice, sugar, soybeans, auto parts, and other products. Over the past three years, India has cut its purchases of Iranian oil at some cost to its own development, and has received from the U.S. Administration the authorized exemptions from U.S. sanctions for doing so. By mid-2013, Iran was only supplying about 6% of India’s oil imports (down from over 16% in 2008)—reflecting significant investment to retrofit refineries that were handling Iranian crude. India’s private sector has come to view Iran as a “controversial market”—a term used by many international firms to describe markets that entail reputational and financial risks. As a result, investment in Iran by Indian firms, including in Iran’s energy sector, has been largely dormant over the past four years. However, Indian investment in Iran, as well as oil purchases from Iran, are expecting to rise sharply once sanctions are lifted or suspended under the JCPOA.

Some projects India has pursued in Iran involve not only economic issues but national strategy. India has long sought to develop Iran’s Chabahar port, which would give India direct access to Afghanistan and Central Asia without relying on transit routes through Pakistan. India had hesitated to move forward on that project because of U.S. opposition to projects that benefit Iran. After the JPA, India announced it would proceed with the project, but there has been little actual construction done at the port to date.83 The JCPOA, once fully implemented, will likely cause the Chabahar project to move forward significantly.

As noted above, in 2009, India dissociated itself from the Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline project. India publicly based its withdrawal on concerns about the security of the pipeline, the location at which the gas would be transferred to India, pricing of the gas, and transit tariffs. However, the long- standing distrust and enmity between India and Pakistan likely played a significant role in the Indian pullout. These issues will not be addressed by the JCPOA, making India’s return to that project still unlikely. During economic talks in July 2010, Iranian and Indian officials reportedly raised the issue of constructing a subsea natural gas pipeline, which would bypass Pakistani territory.84 However, an undersea pipeline would be much more expensive.

During the late 1990s, U.S. officials expressed concern about India-Iran military-to-military ties. The relationship included visits to India by Iranian naval personnel, although India said these exchanges involved junior personnel and focused mainly on promoting interpersonal relations and not on India’s provision to Iran of military expertise. The military relationship between the countries has withered in recent years.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka was a buyer of small amounts of Iranian oil until 2012, when U.S. sanctions were imposed on countries that fail to reduce purchases of Iranian oil. Shortly thereafter, Sri Lanka ended its oil purchases from Iran and in June 2012, the country received an exemption from U.S. sanctions. The JCPOA will likely cause Sri Lanka to resume oil purchases from Iran.

Russia

Iran appears to attach significant weight to its relations with Russia, which is a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council and the member of the P5+1 that was the most accepting of some of Iran’s positions in the JCPOA talks. Strategically, Iran and Russia are aligned in Syria – the two countries are the main international backers of the Asad regime.

Russia has been Iran’s main supplier of conventional weaponry and a significant supplier of missile-related technology. Russia built and still supplies fuel for Iran’s only operating civilian nuclear power reactor at Bushehr, a project from which Russia earns significant revenues. Russia and Iran reportedly are negotiating for Russia to build at least two additional nuclear power plants in Iran.

Despite its commercial and military involvement with Iran, Russia has abided by all U.N. sanctions, even to the point of initially cancelling a contract to sell Iran the advanced S-300 air defense system after Resolution 1929 banning arms exports to Iran was adopted—even though the resolution did not specifically ban the sale of the S-300. After the April 2, 2015, framework nuclear accord was announced, Russia lifted its ban on the S-300 sale. By all accounts, the system has not been delivered to date, but Russia might be waiting until after “Implementation Day” of the JCPOA (the point where Iran is deemed compliant with initial nuclear tasks and most sanctions are lifted) to go ahead with the shipment. Some reports suggest that in 2015 a Russian defense firm might also have offered to sell Iran the advanced Antey-2500 air defense system.85 In January 2015, Iran and Russia signed a memorandum of understanding on defense cooperation, including military drills.86

Other issues similarly align Iran and Russia. Since 2014, Iran and Russia have apparently both seen themselves as targets of Western sanctions (over the Ukraine issue, in the case of Russia). Iran and Russia have also separately accused the United States and Saudi Arabia of colluding to lower world oil prices in order to pressure Iran and Russia economically. In August 2014, Russia and Iran reportedly agreed to a broad trade and energy deal which might include an exchange of Iranian oil (500,000 barrels per day) for Russian goods87—a deal that presumably would go into effect if sanctions on Iran were lifted. Russia is an oil exporter, but Iranian oil that Russia might buy under this arrangement would presumably free up additional Russian oil for export. Iran and Russia reaffirmed this accord in April 2015.

Some argue that Iran has largely refrained from supporting Islamist movements in Central Asia not only because they are Sunni movements but also to avoid antagonizing Russia. Russia has faced attacks inside Russia by Sunni Islamist extremist movements and Russia appears to view Iran as a de-facto ally in combating such movements. These common interests might explain why Iran and Russia are each assisting the Asad regime against the armed insurgency led by Sunni Islamist groups.

Europe

U.S. and European approaches on Iran have converged since 2002, when Iran was found to be developing a uranium enrichment capability. Previously, European countries had appeared somewhat less concerned than the United States about Iranian policies and were reluctant to sanction Iran. After the passage of Resolution 1929 in June 2010, European Union (EU) sanctions on Iran became nearly as extensive as those of the United States.88 In 2012, the EU banned imports of Iranian crude oil and natural gas. Still, the EU countries generally conducted trade relations in civilian goods that are not the subject of any sanctions. The EU is a party to the JPA and the JCPOA, and, in concert with the agreement, the EU is lifting nearly all economic sanctions on Iran in connection. Several high-level European delegations have visited Iran since JCPOA was finalized, most of which included business executives seeking to resume business relationships mostly severed since 2010. France opened a formal trade office in Tehran in September 2015.

Iran also always maintained full diplomatic relations with all the EU countries, with the exception of occasional interruptions caused by Iranian assassinations of Iranian dissidents in Europe or attacks by Iranian militants on EU country diplomatic property in Iran. There are daily scheduled flights from several European countries to Iran, and many Iranian students attend European universities. Iran did not break relations with the EU or with any EU countries when, in July 2013, the EU designated the military wing of Lebanese Hezbollah as a terrorist organization, an action that followed the attack on Israeli tourists in Bulgaria in 2012 (see table above). After the JCPOA was finalized, British Foreign Secretary Phillip Hammond visited Iran and reopened Britain’s embassy there – closed since the 2011 attack on it by pro-government protesters.

During the 1990s, U.S. and European policies toward Iran were in sharp contrast. The United States had no formal dialogue with Iran; however, EU countries maintained a policy of “critical dialogue” and refused to join the 1995 U.S. trade and investment ban on Iran. The EU-Iran dialogue was suspended in April 1997 in response to the German terrorism trial (“Mykonos trial”) that found high-level Iranian involvement in killing Iranian dissidents in Germany, but it resumed in May 1998 during Mohammad Khatemi’s presidency of Iran. In the 1990s, European and Japanese creditors bucked U.S. objections and rescheduled about $16 billion in Iranian debt bilaterally, in spite of Paris Club rules that call for multilateral rescheduling. During 2002-2005, there were active negotiations between the European Union and Iran on a “Trade and Cooperation Agreement” (TCA) that would have lowered the tariffs or increased quotas for Iranian exports to the EU countries.89 Negotiations were discontinued in late 2005 after Iran abrogated an agreement with several EU countries to suspend uranium enrichment. Also, although the U.S. Administration ceased blocking Iran from applying for World Trade Organization (WTO) membership in May 2005, there has thus far been insufficient international support to grant Iran WTO membership.

East Asia

East Asia includes three large buyers of Iranian crude oil and one country, North Korea, that is widely accused of supplying Iran with WMD-related technology. The countries in Asia have sometimes joined multilateral peacekeeping operations in the Middle East but have not directly intervened militarily or politically in the region in the way the United States and its European allies have. Countries in Asia have rarely been a target of official Iranian criticism.

China90

China, a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council and one of the P5+1 countries that negotiated the JCPOA, is Iran’s largest oil customer. China has also been a supplier of advanced conventional arms to Iran, including cruise missile-armed fast patrol boats that the IRGC Navy operates in the Persian Gulf. There have been reports that, particularly prior to 2010, some Chinese firms had supplied ballistic missile guidance and other WMD-related technology to Iran.91 During U.N. Security Council deliberations on sanctioning Iran for its nuclear program during 2006-2013, China tended to argue for less stringent sanctions and for more deference to Iran’s positions than did the United States, France, Britain, and Germany.