Che Guevara In The Congo – OpEd

By David Seddon*

The idea of Guevara as a latter-day Don Quixote, setting out on his adventures to undo wrongs and bring justice to the world, and, despite a series of disastrous encounters, managing to survive with spirits undiminished until the very end, is one that appeals to the romantic in all those who see themselves as revolutionaries.

Introduction

The recent death of Fidel Castro on 25 November 2016 prompted me to re-visit the extraordinary history of the Cuban Revolution and in particular the role of the Cuban government under Castro in supporting what they considered to be progressive movements and radical governments throughout the world, including in Africa, over a period of three decades from the 1960s to the 1980s. Diplomatic recognition, political support and military assistance were all provided to national liberation struggles and independent states in Algeria and Western Sahara, in Eritrea and Ethiopia, in Zanzibar, and in the Portuguese colonies of Guinea-Bissau, Angola and Mozambique. The military victories won by Cuban soldiers in Angola, in 1975-76 and again in 1987-88, against the South African army were in my opinion a crucial part of the eventually successful struggle against White rule in Namibia and in South Africa itself.

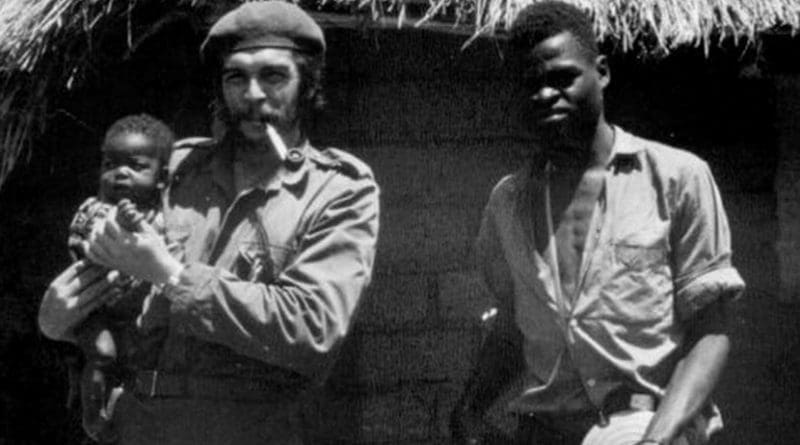

Cuba first helped the Algerian liberation struggle in 1961, sending a large consignment of American weapons captured during the abortive Bay of Pigs invasion; and after Algeria gained independence in July 1962, the Algerians reciprocated by helping to train a group of Argentinian guerrillas, even sending two agents with the guerrillas from Algiers to Bolivia in June 1963. But the earliest attempt to provide systematic support to a potentially revolutionary movement in Africa involved sending an elite group of Cuban guerrillas – all volunteers and the majority of them black – to the eastern Congo in 1965. One of the few white Cuban guerrillas involved was Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara.

The Congo: background

The Congo’s independence from Belgium had been followed in June 1960 by the election of a left-wing prime minister, Patrice Lumumba. This in turn was followed in rapid succession by an army mutiny, the secession of the country’s mineral-rich province of Katanga under Moise Tshombe, the return of Belgian troops, and the arrival of United Nations peace-keeping forces, at Lumumba’s request, to protect the country’s territorial integrity and his new regime. When Lumumba also asked for Soviet military assistance he was deposed by President Kasavubu, whose decision was supported by the commander-in-chief, Joseph Mobutu. The subsequent murder of Lumumba and the death in a plane crash of the UN Secretary-General, Dag Hammarskjold, led to a chaotic situation in the Congo.

By early 1964, the country was left in the hands of a weak and unpopular prime minister, Cyrille Adoula, who had closed down the Congolese parliament, the UN was planning to withdraw and four different rebellions had broken out, most of them operating under an umbrella group of leftist opposition groups called the National Liberation Council, that had effectively replaced the parliament. One of the rebel movements, which affected the northeast of the country, was led by a local politician, Gaston Soumaliot, whose lieutenant, Laurent Kabila, orchestrated a related movement further south. For a few weeks in mid- 1964, these rebel forces controlled much of the eastern region of the Congo. Meanwhile, a former colleague of Lumumba’s, Christophe Gbenye, backed by China and the Soviet Union, controlled much of the rest of the country.

In March 1964, President Lyndon Johnson sent Averell Harriman to Leopoldville (Kinshasa) to assess the situation. Together with Cyrus Vance, the US deputy defence secretary, Harriman drew up plans for an American airlift to the Congo, and in May, planes and helicopters began arriving. In July, Moise Tshombe seized power, replacing the ineffective Adoula, and called for help from the USA, Belgium and South Africa to support his regime. His call was heeded and the Congolese army was reinforced by Belgian officers and white mercenaries from Rhodesia and South Africa. The main immediate task was to crush the rebellion of Gbenye, who had established his headquarters and government in Stanleyville (Kisangani). In November, Belgian paratroopers were flown in from Britain’s South Atlantic base on Ascension Island with the permission of the newly elected Labour government under Harold Wilson and dropped on Stanleyville, at the same time as the mercenaries arrived.

Guevara looks to Africa

In response, a group of radical ‘front-line’ African states led by Algeria and Egypt announced that they would supply the Congolese rebels with arms and troops, and called on others for help. The government of Cuba announced that it was ready to oblige. In December, Guevara – already one of the most internationalist of the Cuban leadership – made an impassioned speech, in his capacity as the Cuban delegate to the UN General Assembly, in which he referred to the ‘tragic case of the Congo’ and denounced ‘this unacceptable intervention’ by the Western powers, referring to ‘Belgian paratroopers and transport by US aircraft, which took off from British bases’.

Leaving New York, he embarked on a tour of African states, visiting first Algeria and then Mali, Congo-Brazzaville, Senegal, Ghana, Dahomey, Egypt and Tanzania. In Dar es Salaam, he met Laurent Kabila, who sought help to maintain what was left of the liberated area in the east and southeast of the Congo, and in Cairo, he met Gaston Soumaliot who wanted men and money for the Stanleyville front in the Congo; and in Brazzaville, he met Agostinho Neto, who requested the Cubans to provide support for the Angolan liberation army, the MPLA. He was excited by what these men told him about the potential for an effective liberation struggle – and for a role for Cuba in providing support – in these three cases.

In February 1965, Guevara flew to Beijing to see what help the Peoples’ Republic of China might provide to the rebellions in the Congo. There he met, among others, Chou en Lai (who between December 1963 and February 1964 had himself visited some ten African countries with a view to assessing how best China might intervene). Soon after his meeting with Che in Beijing, Chou was to make a second visit to Algiers and Cairo, in March 1965, possibly to meet the Congolese rebel leaders about whom Che had informed him, and then in June, he flew to Tanzania where he certainly met both Kabila and Soumaliot.

In the meanwhile, Guevara himself flew back to Cairo, where he talked with Colonel Nasser about his plan to lead a group of guerrillas himself. According to an account of the meeting by Nasser’s son-in-law, the editor and journalist Mohammed Heikal, Nasser was less than enthusiastic and warned Guevara about the dangers of romanticism – and warned him ‘not to become another Tarzan’; ‘it can’t be done’, he said. Guevara was clearly not impressed by this sceptical response. He was already, I suspect, a man with a mission – which was to bring his own personal experience of helping build a revolutionary movement (that had been so successful, in his view, in Cuba, and had been achieved by a handful of committed guerrillas) to bear on other situations elsewhere in the world.

Guevara returned to Cuba, to be greeted at the airport by Fidel Castro. It was the last time he would be seen again in public, until after his death two and a half years later in October 1967, in Vallegrande in Bolivia. Before he left Cuba he wrote a farewell letter to Fidel – which was read out publicly in Havana six months later, in October 1965 – in which he effectively declared that he no longer felt obligated to the Cuban Revolution but to the project of extending its influence and its impact elsewhere: ‘other nations are calling for the aid of my modest efforts… I have always identified myself with the foreign policy of our Revolution, and I continue to do so’. It was a statement made by a man who felt that his destiny was now to ‘export’ the revolution by leading a guerrilla movement in Africa. If he had been able to integrate, as an outsider and an Argentinian, with the Cuban revolutionaries, why not with African revolutionaries, whether in Angola or in the Congo?

Three weeks later, he flew secretly from Havana with a small group of Cuban troops, first to Cairo and then to Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. Tanzania was at that time a leading radical African state under President Julius Nyerere, which had just created a union with revolutionary Zanzibar. While one ‘column’ of 120 Cubans was to be shipped piecemeal to Tanzania and across Lake Tanganyika into North Katanga, a second ‘column’ of 200 men (the ‘Patrice Lumumba battalion’) was to fly to a base on the other side of the country, near Brazzaville, across the Congo River from Leopoldville (Kinshasa), the capital of the Congo. The eastern ‘column’ was to be officially led by Captain Victor Dreke – a Cuban of African descent about whom Che later wrote to Fidel: ‘he was…one of the pillars on which I relied. The only reason I am not recommending that he be promoted is that he already holds the highest rank”. Guevara was part of this ‘column’. The western ‘column’ was to be led by Jorge Risquet Valdes Santana, a member of the central committee of the Cuban Communist Party.

Guevara’s group was greeted at the airport outside Dar es Salaam by the new Cuban ambassador, Pablo Rivalta; the Embassy had been established only a few months before. Guevara was concerned that their arrival risked being noticed by the CIA, but the Americans had just withdrawn their ambassador from Dar and were otherwise occupied. The Congolese in Dar, however, also paid them little attention. The rebel leaders, including Kabila and Soumaliot, were away in Cairo supposedly trying to reduce the political divisions within their revolutionary movement, and only relatively junior personnel were available. It seems that the planning for the Cuban intervention in the African armed struggle was, from the outset, somewhat lacking and that co-ordination with the African leaders was somewhat limited.

Nevertheless, on 22 April 1965, Guevara and his small group of Cubans travelled by road to the lakeside town of Kigoma, where they established a supply base. Near Kigoma is the village of Ujiji, where Dr David Livingstone and Mr Henry Stanley had met a century before, in 1871. It is not known whether Guevara was aware of this well-known episode in the history of imperialism in Africa, or of the proximity of Ujiji to his anti-imperialist base in Kigoma, but he was savvy enough to give each of the Cuban leaders a number in Swahili – Dreke was Moja (one), Tamayo, a close collaborator of Guevara’s over several years and already one of the most significant figures in Cuba’s international military activities, was Mbili (two) and Guevara himself, misleadingly and confusingly as it turns out, was Tatu (three).

The Cubans crossed the lake and were welcomed at the village of Kibamba by a well-armed group of the People’s Liberation Army, dressed in khaki fatigues provided by the Chinese. They communicated with the Cubans in French. The Cubans made camp just outside the village. This was the start of what was to be a seven -month campaign in what the mercenary leader Colonel Mike Hoare called ‘the Fizi Baraka pocket of resistance’ against the Tshombe regime, which covered an area twice the size of Wales. Over the next few months, between April and October 1965, more Cubans arrived, in dribs and drabs, from across Lake Tanganyika, to join their compatriots and together the Cubans and the Congolese developed a plan to explore the terrain they ‘occupied’ and the Cubans began to assess the strengths and weaknesses of their allies, and of their enemies.

As regards the latter, they noted in their exploratory sorties that the forward bases of the enemy were well defended, supported by small planes and helicopters and white mercenaries; as regards the former, they considered the morale and the competence of the Congolese rebels to be low and found that their leaders, including Kabila, were regarded as strangers – or more pejoratively still as ‘tourists’. The commanders in the field ‘spent days drinking and then had huge meals without disguising what they were up to from the people around them. They used up petrol on pointless expeditions’. On 7 June, in an unexplained accident, the most senior rebel leader present (Kabila was still in Dar es Salaam), Leonard Mitoudidi, was drowned in Lake Tanganyika.

Not long afterwards, instructions came from Kabila that the Cubans should organise an attack on a garrison at Bendera on the inland road which was defending a hydro-electric plant. Guevara was unhappy with the plan; but it was decided to go ahead anyway. On 20 June 1965, a combined force of Cubans, Congolese and Tutsis (some of whom were originally from Rwanda) set off with the idea of attacking the plant and the barracks. The operation was felt by the Cubans to be a disaster – many of the Tutsis ran away, the Congolese refused to take part, and four Cubans were killed, revealing to the enemy that Cuba was now involved in the rebellion on the ground. Colonel Mike Hoare, on the other hand, was apparently impressed and noted in his memoirs that ‘observers had noticed a subtle change in the type of resistance which the rebels were offering the Leopoldville government… The change coincided with the arrival in the area of a contingent of Cuban advisers specially trained in the arts of guerrilla warfare’.

The Cubans, however, were depressed and disillusioned. All of the Cubans had been ill at one time or another since their arrival; Guevara himself suffered from bouts of asthma and malaria. There were small military successes – like the ambush of a group of mercenaries in August. But progress appeared to be negligible and the political climate was undoubtedly deteriorating. Differences between the various rebel factions and their leaders seemed to be coming to a head, and a coup d’etat in Algeria, which replaced Ben Bella – one of Guevara’s principal supporters – by Houari Boumedienne, the army commander, led to a reduced commitment to the Congolese rebellion on the part of the international community of radical states. But Guevara kept his concerns to himself and when Soumaliot went to Havana early in September 1965 he was able to convince Castro that the revolution was going well; and nothing was done to stop the regular monthly flow of newly trained guerrillas arriving in Tanzania from Cuba.

The white mercenaries, together with the Congolese troops of Tshombe, were now developing a counter-attack, which threatened the entire Cuban position. However, the Cuban training must have counted for something, for, as Hoare recorded later, ‘the enemy were very different from anything we had ever met before. They wore equipment, employed normal field tactics, and answered to whistle signals. They were obviously being led by trained officers. We intercepted wireless messages in Spanish… and it seemed clear that the defence… was being organised by Cubans’. But by October, after the Cubans had been in the Congo for barely six months, they and their Congolese allies were on the back foot. Guevara was forced to retreat to their Luluabourg base camp and foresaw a long, last resistance.

Events, however, proved as unpredictable as ever, and President Kasavubu was eventually convinced that he would never get the approval of the majority of African states in the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) if Tshombe continued as prime minister and effectively lord of Katanga, and so Tshombe was sacked and replaced by Evariste Kimba. It looked for a moment as though the rebellion was saved, but in reality the ‘overthrow’ of the Tshombe government was to prove the prelude to a political reconciliation that would undermine the rebellion and lead to the collapse of the support it had been receiving from African states.

On 23 October 1965, Kasavubu attended a meeting of African heads of state in Accra, presided over by Kwame Nkrumah. He announced that the rebellion in the Congo was virtually at an end and it would, therefore, be possible to dispense with the services of the white mercenaries, and to send them home.

This was enough to sway many African leaders. It was a signal defeat for the radical African states and enabled a more conservative alliance to emerge in the OAU and marked a turning point in the late colonial history of the African sub-continent. On 11 November 1965, sensing that the climate was now favourable, Ian Smith, the White Rhodesian leader unilaterally declared independence from the United Kingdom; in South Africa there was a renewed attack on the ANC which effectively crushed the mass movement against apartheid for half a decade; and the Portuguese were encouraged to maintain their grip on Angola, Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau for another decade, until 1975. Ben Bella, as previously indicated, was overthrown; Nkrumah was removed from power while on a visit to China early in 1966, and ‘the Mehdi’ Ben Barka, the Moroccan radical leader who had been organising Cuba’s Tri-Continental Conference – a gathering of revolutionary movements from all over the world, to be held in Havana in January 1966 – was kidnapped in Paris and murdered.

Meanwhile, back in the Congo, when Mike Hoare heard of Kasavubu’s speech and pledge to send the mercenaries home, he flew to Leopoldville to see Mobutu in person. ‘The general was furious’, he recalls, ‘he had not been consulted…and felt bitter in consequence’. Kimba, the new prime minister, was persuaded to make a statement to the effect that there was no intention of sending the mercenaries home until the Congo was thoroughly pacified. Guevara was also struggling with the turning political tide in Africa. On 1 November 1965 he received an urgent message from Dar es Salaam warning him that the Tanzanian government, as a result of the Accra meeting, had decided to pull the plug on the Cuban expeditionary force. President Nyerere, all too aware of the internal feuding within the Congolese leadership and concerned about its implications, felt he had little choice.

But Guevara had already considered the option of remaining behind, whatever happened, ‘with twenty well-chosen men’. He would then have continued to fight until the movement developed or until its possibilities were exhausted – in which case, he would have decided to seek another front or to request asylum somewhere. It really seems that he felt he still had a mission outside Cuba. He asked for help from China and was advised by Chou en Lai to remain in the Congo, forming resistance groups, but without entering himself into combat. On 20 November, however, he sounded the retreat and organised the crossing of Lake Tanganyika back into Tanzania. ‘All the Congolese leaders’, he wrote, ‘were in full retreat, the peasants had become increasingly hostile’.

Fidel Castro himself would say, years later, that ‘in the end it was the revolutionary leaders of the Congo who took the decision to stop the fight, and the men were withdrawn. In practice, this decision was correct; we had verified that the conditions for the development of this struggle, at that particular moment, did not exist’. Whether that was indeed the case or merely the product of a fait accompli, is debatable. In any case, however, after a few days in Dar es Salaam, most of the Cubans flew home, via Moscow, to Havana, where there was a de-briefing. Victor Dreke returned to Cuba to head a military unit preparing internationalist volunteers; and in 1966, he headed the Cuban military mission to Guinea-Bissau/Cape Verde, where he served alongside Amílcar Cabral. He then performed a similar function in the Republic of Guinea. He returned to Guinea-Bissau in 1986, heading the Cuban military mission until 1989 [1]. Jorge Risquet became Head of the Cuban Civil Internationalist Mission in the People’s Republic of Angola between 1975 and 1979 in support of Agostino Neto and the MPLA.[2] Other members of Guevara’s guerrilla force were also later to be involved once again in Africa.

Che Guevara himself remained after the Cuban military mission, in Dar, in the Cuban embassy, to write his account of the ‘Congolese campaign’. Early in 1966, he travelled to Prague and then, eventually, returned to Cuba, where he helped prepare the expeditionary force that would eventually, in November 1966, establish itself in eastern Bolivia. There, unlike the situation in the eastern Congo where he was prepared to accept the ‘Number Three’ position (as Tatu), for whatever reason, he insisted on openly leading the force. His insistence on this meant that he received no support from the Bolivian Communist Party, which left the Cuban guerrillas effectively isolated.

In March 1967, only three months after they had arrived in the region, the Cubans and their Bolivian allies were discovered by the Bolivians and in April they were forced into action against the Bolivian army. With no external support, the guerrilla band slowly dwindled in numbers and its morale ebbed away. In October 1967, Guevara was captured and shot the next day.

In one way, it might be said that, in deciding to fight on against hopeless odds, he had learned nothing from his experiences in the Congo; in another, it might be said that he had already contemplated such a situation in the Congo, when he seriously considered staying to fight on with ‘twenty well-chosen men’, and probably even from April 1965 when he wrote his letter to Castro, renouncing his positions in the party leadership, his ministry post, his rank of commandante and his Cuban citizenship. He was, after all, let us remember, an Argentinian and not a Cuban; he had always been, to a certain extent, an outsider. He was also an idealist who had travelled widely in Latin America on his motorbike as a young doctor, had become familiar with the lives of the poor and had come to believe that something could be done to change those lives through revolution. He had participated in the extraordinary success of the Cuban Revolution and seen what could be done by a few determined men.

Tellingly, already in 1965, when he left for the Congo, he had written to his parents in Argentina, saying: ‘once again I feel under my heels the ribs of Rocinante.’ The idea of Guevara as a latter-day Don Quixote, setting out on his adventures on his ancient horse to revive chivalry, undo wrongs, and bring justice to the world, and, despite a series of disastrous encounters, managing to survive with spirits undiminished until the very end, is one that appeals to the romantic in all those who see themselves as revolutionaries. It was always, however, a dream – something he recognises in his diaries of ‘the revolutionary war in the Congo’.

See, ‘The African Dream: the Diaries of the Revolutionary War in the Congo’, by Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, Grove Press, New York, 1999. Translated from Spanish by Patrick Camiller; first published in Great Britain by The Harvill Press, London in 2000. Introduction by Richard Gott, Foreword by Aleida Guevara March, paperback, pp. 244.

NB. This account draws heavily on the Introduction by Richard Gott to Ernesto Che Guevara’s account, drawn from his diaries, of the Cubans’ involvement in the rebellions or revolutionary wars in the Congo in the mid-1960s. But some of the commentary is my own, and for that, of course, Gott is not responsible.

* DAVID SEDDON is co-author (with David Renton and Leo Zeilig) of Congo: plunder and resistance, Zed Books. He is also the co-ordinator of a series of essays on ‘popular protest, social movements and the class struggle’, under the project of the same name, published on the RoAPE website between 2015 and 2016.

Notes:

[1] In 1990, after a successful military career, General Dreke retired from active military service. He then acted as representative in Africa for Cuban corporations ANTEX and UNECA in trade and construction projects, and became vice president of the Cuba-Africa Friendship Association.

[2] Even though the Congo campaign led by Che Guevara was not successful in defeating the counter-revolution in 1965, a decade later, the Cuban government would respond to a request by Agostino Neto, the leader of the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) to assist the independence movement in defeating an invasion by the South African Defence Forces (SADF), supported by the U.S. CIA, aimed at installing a puppet western-backed regime in Luanda. Between November 1975 and early 1976, some 55,000 Cuban troops were deployed, which assisted the MPLA’s military wing (FAPLA) in defeating the SADF intervention and consolidating the national independence of Angola. Cuban military units remained in Angola for 16 years fighting alongside the FAPLA forces as well as the South West Africa People’s Organization’s (SWAPO) military cadres of the People’s Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN) and the African National Congress (ANC) armed wing, Um Khonto We Sizwe (MK).

The U.S. and its allies in Pretoria, armed, funded and provided diplomatic cover for both Jonas Savimbi of UNITA and Holden Roberto of the FNLA based in the-then Zaire, which was renamed after the triumph of the counter-revolution in Congo-Kinshasha. UNITA proved to be the most formidable foe since it was given direct assistance by the CIA and the SADF then operating in South West Africa (Namibia) prior to its independence in 1990. This struggle reached its climax in 1987-1988 with battles centered at Cuito Cuanavale where the SADF was routed and defeated in Angola. These battles would convince the racist regime in Pretoria and its backers within the Reagan and Bush administrations that a military defeat against the Southern African liberation movements was not possible. A ceasefire was declared in late 1988 and negotiations were undertaken between the MPLA government in Angola and the apartheid regime.

The U.S. and South Africa did not want the Cuban government involved in the talks aimed at the withdrawal of SADF forces from southern Angola and the independence process in Namibia. Nonetheless, due to the overwhelming support of the-then Organization of African Unity (OAU) and progressive forces internationally, the Cubans were not only allowed into the talks but played a prominent role. The central role of Jorge Risquet in the talks enhanced his international prominence, illustrating the general significance of Cuba in the African revolutionary process. Risquet led the Cuban delegation in the talks that resulted in the withdrawal of the apartheid army from southern Angola and the liberation of neighboring Namibia under settler-colonial occupation for a century. Internationally supervised elections were held in Namibia in late 1989, leading to the declaration of independence on March 21, 1990, under the leadership of President Sam Nujoma of SWAPO, which won overwhelmingly in the elections.

The independence of Namibia and the ongoing mass and armed struggles in South Africa led by the ANC, forced the removal of P.W. Botha, the-then president of the apartheid regime, and the ascendancy of F.W. DeKlerk. The new regime began to indicate that it was willing to negotiate an end to the political crisis in South Africa: on February 2, 1990, the ANC, the South African Communist Party (SACP) and other previously banned organizations were allowed to function openly; nine days later, on February 11, Nelson Mandela was released after over 27 years of imprisonment in the dungeons of the racist apartheid system.