Resolving South China Sea Dispute Critical For World Peace – Analysis

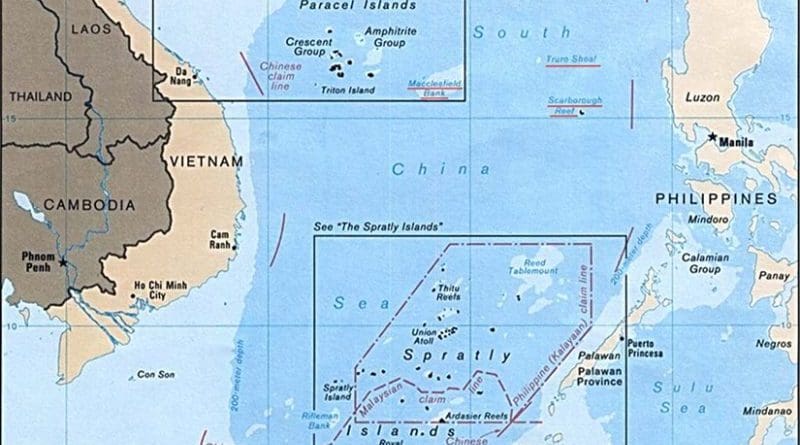

The South China Sea (SCS) has emerged as a major flashpoint in the Asia Pacific region. There are several claimants to this disputed maritime territory. Several smaller nations of the ASEAN grouping claim to some parts of the SCS which are in their exclusive economic zones. On the other hand, China claims its sovereignty over this maritime space almost in its entirety. It even rejected the ruling in July 2016 of the international tribunal which ruled that China’s claims lack any historical validity. It has declared the SCS as one of its core interests, along with Tibet and Taiwan. Over the years, China is engaged in various activities such as island building, making new fishing zone, with the aim to take control of this ocean space to the exclusion of other claimants.

When the Hague tribunal invalidated most of its claim over the SCS in a case brought by the Philippines, China was enraged. Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte who had taken office a month before the ruling, downplayed the ruling with a view to improve his country’s relations with China. Despite Duterte’s attempt to mollycoddle ties with China, China protested when Philippines’s defence and military chiefs visited to a disputed island in the SCS. The Philippine government maintained that it owns the territory where Filipino troops and villagers have lived for decades.

In order to achieve its objectives, China has tried to create disunity amongst the ASEAN states. At other times, it has used economic diplomacy to get a certain member state of the grouping into its fold. For example, China took maximum advantage of the Philippines when controversial Duterte took power and willingly tried to reach out to Beijing. According to a recent report, China had even installed rocket launchers on the disputed Fiery Cross Reef in the SCS, though China claims that the facilities would be limited to defensive requirements.

China’s militarisation drive

Resolving the dispute over contending territorial claims on the SCS by several countries at the soonest is paramount in the interest of securing peace and stability in the region. But China unilaterally continues to militarize the disputed territories without any consideration for the sensitivities of smaller nations who have their own legitimate claims. There are evidences that China has nearly completed structures intended to house surface-to-air missile systems on its three largest outposts in the disputed territory as part of a steady pattern of its militarization. Such structures have come up at Fiery Cross Reef, Mischief Reef and SubiReef, all man-made islands dredged by China and are now home to military-grade airfields. China started construction of these buildings in September 2016 and thus far built eight buildings on each of three outposts.

Whether or not the Chinese move is in response to America’s attempt to check Chinese assertiveness in the SCS is not important; what is a matter of concern is that it is a systematic part of a well-defined strategy of militarization by China to strengthen its stronghold in this oceanic space. China sent HQ-9 SAMs with a range of up to 200 km to its outpost on Woody Islands in the Paracel chain in the strategic waterway. The deployment of SAM batteries is aimed to extend its defence capabilities throughout its so-called nine-dash line claim to the waters and therefore project power. Dishonouring the pledge by Chinese President Xi Jinping made in 2015 not to “militarize” the islands, Beijing has gone ahead to add anti-aircraft and anti-missile systems on the man-made islets. Xi Jinping never defined his policy of not to militarize, arguing now that these deployments are necessary to defend the islands.

Beijing has several advantages from these structures on the islands. The “shelters would conceal launchers from view, thwarting overhead surveillance and preventing adversaries from knowing how many launchers (if any) are present at any given time”. Beijing claims these measures are in accordance with the nation’s security requirements and are the legitimate right of a sovereign state.

As expected, such Chinese activities raise alarm in other Asian capitals which have similar claims on the disputed territories. While none of the claimants are in a position to confront China militarily, they look at Washington and other stakeholders who do not have direct involvement in the dispute but respect global rules to come to their rescue to prevail upon Beijing from pursuing such an aggressive approach. In any given circumstance, there can be no better substitute than pursuing assiduously dialogue as the only desirable option to address the issue. At the same time, military preparedness to confront China if the situation so warrants cannot be abandoned either. It is therefore of paramount importance that a Code of Conduct (COC) should be the key to resolving disputes in accordance with international law.

The US has responded in flexing its own military muscle to end a clear message to China not to mess up things by precipitating the dispute. It sent its Carrier’s Strike Group 1, which includes the Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson, into the SCS, the first such “routine operation” in the waterway under the Trump administration. China reacted by observing that “the constant reinforcement of military deployment in the SCS by some countries outside the region goes against the endeavor of regional countries to seek peace and security, and it is not in the interests of the regional countries.”

Though the carrier strike group did not refer to its operations in the SCS as “freedom of navigation” patrols, it was a clear demonstration of its intention to limit Beijing’s excessive maritime claims. Beijing sees the US move as the greater military threat to peace in the waterway. It perceives the US deployment as a direct military threat. The nationalistic Global Times warned in an editorial that “If the U.S. military insists on showing that it is capable of taming the China Dragon, they are bound to see all kinds of advanced Chinese weapons as well as other military deployments on the islands.”

FONOPs

President Donald Trump has resolved to challenge Beijing and restore order in the SCS. The US Navy is soon to restart Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) to challenge claims by China to exclusive access in the sea. The temporary suspension of the “freedom of navigation” patrol was because of transition of administration in Washington. The SCS remains a priority for the Trump administration.

Since Trump too office on 20 January, the US Navy did not conduct any FONOPs near areas claimed by China in the SCS. In such operations, the US ships or planes go near “disputed” Chinese features to test the claims to exclusive access. Washington is aware that it needs to demonstrate its commitment to its allies in such critical situations. Beijing is always paranoid with the US military presence, saying that it is only stirring regional tensions. The Trump administration is unlikely to loosen its grip as China continues to build massive military complex in the middle of the SCS.

Need for the COC

This waterway has enormous strategic significance for many countries. Besides home to rich fishing grounds and a potential wealth of oil, gas and other natural resources beneath the ocean floor, an estimated $5 trillion in global trade annually passes through the SCS. Besides China, Brunei, Malaysia, Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan also have claims. Issues involved in the dispute are freedom of navigation, maritime security, rules of law, global norms governing international trade and the COC. In a major development, China and Southeast Asian countries agreed on 18 May to a draft framework on the rough outline of a legally binding COC designed to prevent clashes in the strategic maritime territory.

Fifteen years ago, China and the members of the ASEAN grouping had committed to draft the COC but were unable to do so because of differences. Having committed to the draft, there are concerns within the ASEAN about whether China is expected to be sincere, or whether ASEAN has enough leverage to get Beijing to commit to a set of rules. Though mid-2017 was the timeline set by China and the leaders of the ASEAN, the draft framework was agreed upon before that date, though details of the contents are not yet revealed.

A joint press statement issued at the end of the one-day meeting of representatives of China and 10 members of the ASEAN at Guiyang in Guizhou province stated that all parties “uphold using the framework of regional rules to manage and control disputes, to deepen practical maritime cooperation, to promote consultation on the code and jointly maintain the peace and stability of the SCS”. Now the draft framework shall be submitted to the Southeast Asian foreign ministers meeting in Manila in August for its consideration.

The COC is a document that is expected to address reducing the risk of clashes in one of the world’s heaviest waterways. Liu Zhenmin, Deputy Foreign Minister of China observed: “The draft framework contains only the elements and is not the final rules, but the conclusion of the framework is a milestone in the process and is significant. It will provide a good foundation for the next round of consultations”. Till its final approval, the draft document shall remain as an internal document and confidential. Therefore, its details shall remain unknown for some time.

With China on board, in theory the ASEAN nations could expect to tame China and see it behaves responsibly but it would remain an open question whether Beijing will be willing to halt its activities of constructing artificial islands and loosen its pursuit of effectively controlling the disputed territory. Given China’s obstinate stance on the SCS, the ASEAN states are unlikely to be able to have much leverage to ask Beijing to respect the rules.

The Philippines chairs this year’s ASEAN meetings and started first bilateral consultations with Beijing over the SCS issue. Neither revealed what transpired in the meeting, preferring to keep it confidential for the time being. No date was also given for the adoption of a full COC.

It looks a positive sign that the Philippines chose a pro-active stance after initially cozying with Beijing. In April 2017, the Philippines hosted the 30th ASEAN summit. It highlighted a watered-down communiqué that evaded reference to China’s maritime encroachment in the SCS. Analysts express disappointment that ASEAN states have rather been soft on China’s aggressive activities in the sea. They fear that Beijing might be emboldened to step up its incursion in the area and this in turn could undermine ASEAN’s centrality. The non-issuance of a joint statement in the June 2016 meeting of ASEAN leaders and China at Kunming is cited as the result of the kind of pressure China applied on the ASEAN leaders.

Since the time of The Hague ruling, dialogue and consultations with China by the ASEAN grouping have restored some of the confidence, if not “turned a new page” on dealing with the SCS issue. With the Philippine fishermen regaining access to Scarborough Shoal after years of being blocked by Chinese ships, tensions between the Philippines and China eased to some extent. But distrusts have not disappeared.

It took 15 years to reach at a draft on the COC, which is yet to be finalized, leading to expansion of differences as China toughened its aggressive stance. In the absence of such an agreement, the parties followed a separate document called the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties (DOC), which among other provisions, commits the parties to “exploring ways for building trust and confidence… on the basis of equality and mutual respect”. When the member states and China signed the DOC in November 2002 in Cambodia after several years of prolonged negotiations, it was hailed as a milestone document. Though it did not fulfill its mission to build greater trust between the claimant states and prevent the dispute from escalating, it played the role of imposing moral constraints on relevant parties. It was seen as a compromise between the two positions of doing nothing and having a legally-binding agreement. It served as a reference point when problems and tensions emerged and the grounds for negotiations of a formal COC.

The Philippines is going to host another second leaders-level meeting in November together with ASEAN’s dialogue partners such as Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, Russia and the US. It is to be seen if some sort of consensus is reached and a new direction found to resolve to the contentious SCS issue. Though the draft for the COC has been kept confidential, but it will not be complete without having a mechanism for resolving disputes in the SCS, lack of legitimacy and commitment to demilitarization of disputed islands by China. The formal and binding COC should be discussed and concluded when Manila hosts the ASEAN foreign ministers in August 2017 by adoption and implementation in letter and spirit of all parties.

Vietnam’s stance

Vietnam does not want a fight with China and favors a solution to the dispute under international law but would not hesitate to repulse if Beijing resorts to unilateral actions that is against Vietnam’s national interests. Historically, it has stood its ground by first defeating the French and then the US. But it does not want to suffer from the shadow of history as it wants peace, which is why the Obama administration decided to lift the arms embargo that was in place for a long time.

Vietnam rejects as Beijing seeks to change the status quo in the SCS. It opposes that China is building artificial islands on the Gaven Reefs, a part of the disputed Spratly Islands and located in the middle of the SCS between Vietnam and the Philippines. Unfortunately, no initiative by any of China’s neighbors thus far has succeeded in persuading Beijing to change tack. This leaves Vietnam with no other option than to enhance its military capability by deepening defence ties with friendly countries such as Japan and India. While it seeks a solution to the dispute in accordance with international law and the UN Charter, it sticks to its policy to build alliances with countries but not to fight with another one. It has suffered a lot during the battles of the Cold War and does not want a repeat of the same. That is an understandable position.

China’s aggressive intent

Despite the efforts by the countries in Asia having claims in the SCS to make peace with China and US warning to China not to precipitate things, China remains undeterred. In the latest Chinese move, two Chinese J-10 warplanes intercepted a US Navy P-3 that was operating in international airspace in late May 2017. The Pentagon was concerned by this “unsafe and unprofessional” encounter, though operations were able to continue unimpeded. Around the same time in late May 2017, a US destroyer sailed in disputed SCS waters near a reef claimed by Beijing in the first “freedom of navigation” exercise under Trump.

16th Asia Security Summit

The maneuvers came ahead of a major regional security summit, the 16th, in Singapore from 2-4 June 2017. The IISS-Shangri-La Dialogue is Asia’s premier defence summit, a unique meeting of ministers and delegates from over 50 countries. This year, the keynote speech will be given by Malcolm Turnbull, the Prime Minister of Australia.

Launched in 2002, the IISS Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore has built confidence and fostered practical security cooperation by facilitating easy communication and fruitful contact among the region’s most important defence and security policy makers.

The Dialogue’s agenda is intentionally wide-ranging, reflecting the many defence and security challenges facing a large and diverse region. Over the years ministers have used the Dialogue to propose and advance initiatives on important security issues. These include maritime security in the Malacca Strait, the implications of regional states’ submarine capabilities, the proliferation of small arms and light weapons, regional security architecture, humanitarian and disaster relief, and the idea of a ‘no first use of force’ agreement in the SCS.

The summit has been a useful venue for bilateral, trilateral and multilateral meetings with security partners. While the precise content of these private meetings has usually remained confidential, they have sometimes resulted in public joint statements on defence and security cooperation in the region. Basically it should focus on maritime security challenges, including the militarization of the SCS and discuss how Asian major powers like Japan, India and China could contribute to regional security.

*Professor (Dr.) Panda is currently Indian Council for Cultural Relations India Chair Visiting Professor at Reitaku University, Japan. The views expressed are the author’s own and do not represent either of the ICCR or the Government of India. E-mail: [email protected]