Finding Opportunities in Japan’s Aging Population – Analysis

By FSI

By Antonio Emmanuel R. Miranda*

Japan’s transition into one of the world’s rapidly aging societies continues to be manifested in its declining population. With 26 percent of its population over the age of 65 in 2016, it has the highest share of senior citizens among the members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and is expected to expand into more than 30 percent in 2025. The shrinking population, attributed to the improving life expectancy of Japanese elderly and lower fertility rates, continues to hamper the country’s current efforts at raising productivity and revitalizing the economy. Its impact of a decreasing working-age population, in particular, would prolong Japan’s slow economic growth characterized by lower consumer spending and business activity.

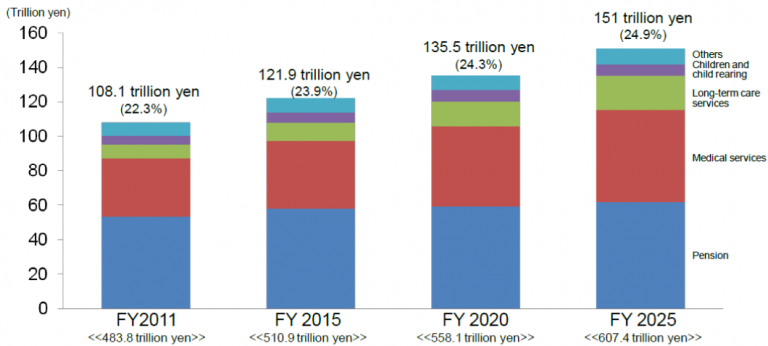

In addition, the increase in social security expenditures to support Japan’s growing elderly will reach JPY 151 trillion in 2025 from its 2011 budget of JPY 108 trillion, thus aggravating the burden on employers and future generations. In addressing the demographic issue, the Japanese government under Prime Minster Shinzo Abe has pledged to implement several structural reforms under the third “arrow” of his Abenomics policy. The significance of reforms in his growth strategy can be observed in its promises of empowerment and capacity-building that function as the foundations of economic recovery. While the first two arrows of expansionary monetary policy and fiscal stimulus have delivered modest results, the long term effects cannot be properly assessed without resolving underlying social conditions that perpetuated Japan’s “demographic time bomb”.

Figure 1: Projection of Japan’s social security expenditures

Curbing the effects of population decline through structural reforms

Seizing the opportunity of a tighter labor market, Japan has advocated greater participation of women in the workforce so as to gradually alleviate the labor shortage problem. Popularly called as “womenomics”, Abe’s policy on women empowerment aims to close Japan’s gender gap by distributing to women 73 percent of jobs in 2020, and 30 percent of managerial roles in 2030. These targets are complemented with the additional construction of 400,000 childcare facilities in 2017 to support women’s needs in childrearing. The immediate results of “womenomics” have indicated significant progress. From 2002 to 2016, the employment rate of women in households with an annual income of JPY 10 million and above increased from 48.6 percent to 56.1 percent, while the number of working women in households earning less than JPY 10 million rose from 55 percent to 64.7 percent. Radical changes in Japan’s rigid company culture, equal wages, and regulatory policies are likely to sustain this positive trend.

Abe has also proposed initiatives towards free education and improved social security to encourage younger families to grow in size. Prior to the dissolution of the House of Representatives in September 2017, he declared his plan for free day care services, kindergarten, and higher education by appropriating JPY 2 trillion of the expected tax revenues from the 10 percent consumption tax hike scheduled in 2019. In the short term, the allocation aims to solve the problem of “waiting lists,” where children of working families have to wait for longer periods before enrollment due to the limited capacity of nursery facilities. These initiatives add on to existing policies for childrearing support, such as universal child allowances for single-parent households.

In balancing the needs of both the young and elderly, Japan has also consistently advocated social security and tax reforms under the revised Revitalization Strategy. The document outlines Japan’s plan to install a sustainable and gender-neutral social security system, high-quality healthcare facilities and services, and a revitalized health industry. The government’s current efforts to realize these goals include the extension of insurance applications to non-regular workers, a review of the household tax and corporate tax, and development of healthcare schemes that combine insured and uninsured medical procedures. While most of these initiatives are fiercely debated for their implications to Japan’s poor fiscal health, the government’s assumed role in sharing expenditures in education and social security premiums would provide more opportunities for Japan’s working class to secure work-life balance that can slowly revive the fertility of its population.

Furthermore, Japan has explored the option of robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) as a viable substitute to human labor. Taking advantage of its position as a “superpower” in the robotics industry, Japan unveiled its New Robot Strategy in 2015 that aspires to induce a “robot revolution”, or the normalization of the use of robotics in all aspects of daily life, such as healthcare, automobiles, manufacturing, and household appliances. The JPY 100 billion strategy is centered on three pillars: creating a global base for robot innovation, maximizing robot capacity, and establishing a new robot era. Aligned with these initiatives, several Japanese companies have expressed their interest in investing on robotics and AI to potentially supply their labor needs and upgrade operations. With the rise in demand for automated processes, the potential of robotics as Japan’s next leading industry would not only enhance the labor market, but also usher a new period of high investment and productivity since Japan’s post-war economic miracle.

Opportunities in an aging society

As structural reforms require more time to develop and monitor, human capital remains as an indispensable and convenient resource that Japan has to cultivate in battling deflation. Apart from encouraging women to join the labor force, Japan is more likely to use its immigration policy as an instrument for replenishing its labor supply. The observed increase in foreign workers and trainees entering Japan indicates that companies are slowly accepting foreign labor as a source of manpower. This trend is a pragmatic step for Japan since an increase in its working-age population, regardless of nationality, is necessary in stimulating consumption and expanding operations. However, cultural barriers remain a considerable challenge to overcoming Japan’s resistance to immigration. With the persistence of Japan’s image as a homogeneous society with a strong group mentality, foreign workers would be vulnerable to forms of alienation, such as low wages and exclusion from benefits. Moving immigration from a temporary solution to a long-term phenomenon forces Japan to face a trade-off between preserving its national identity and embracing fair treatment between nationals and foreigners in job opportunities and social security.

Japan has for years recognized and addressed the increasing demand for healthcare professionals to support its growing elderly population and revive the health industry. An improved immigration policy would encourage the higher intake of foreign professionals, such as doctors and nurses, to Japan. Notwithstanding the positive impact of robotics in enhancing medical services, skilled labor is still a valuable human resource that cannot be completely replaced by AI. However, the language barrier is the underlying liability among foreign professionals who train and practice in Japanese hospitals. The difficulties in learning medical terminology and interacting with local patients and doctors complicate the task of developing sufficient language proficiency. Thus, Japan would be inclined to invest more on its potential healthcare force through intensifying training opportunities, including language training, and easing work restrictions.

Given their vibrant bilateral relations, the Philippines is in good position to help Japan mitigate the challenges of its aging population. For this, the robust implementation of the Japan-Philippines Economic Partnership Agreement (JPEPA) will be essential. The Abe administration has already approved the extension of the period of stay for nurse and caregiver candidates to complete their licensure, internship, and language requirements to work in Japan. Filipino migrant workers who are open to opportunities of permanent residence in Japan would also benefit from the family-friendly reforms under Abenomics – when completely implemented – as these minimize the risks of separation of families. Indeed, by harmonizing the interests of the two countries, Japan and the Philippines can maximize their mutual benefits from investing wisely in their human resources.

About the author:

*Antonio Emmanuel R. Miranda is a Foreign Affairs Research Specialist with the Center for International Relations and Strategic Studies of the Foreign Service Institute. Mr. Miranda can be reached at [email protected]

Source:

CIRSS Commentaries is a regular short publication of the Center for International Relations and Strategic Studies (CIRSS) of the Foreign Service Institute (FSI) focusing on the latest regional and global developments and issues. This article was published by FSI.

The views expressed in this publication are of the authors alone and do not reflect the official position of the Foreign Service Institute, the Department of Foreign Affairs and the Government of the Philippines.