South Asia’s Ambivalence On Ukraine: National Interest And The Burden Of History – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By Ankita Dutta and Trisha Ray

South Asian nations have taken unique, at times divergent positions on the crisis in Ukraine. These positions, on one hand, are driven by their history with the erstwhile Soviet Union and the United States (US) during the Cold War, and on the other, the current global great power competition and South Asia’s relations with these established and emerging great powers.

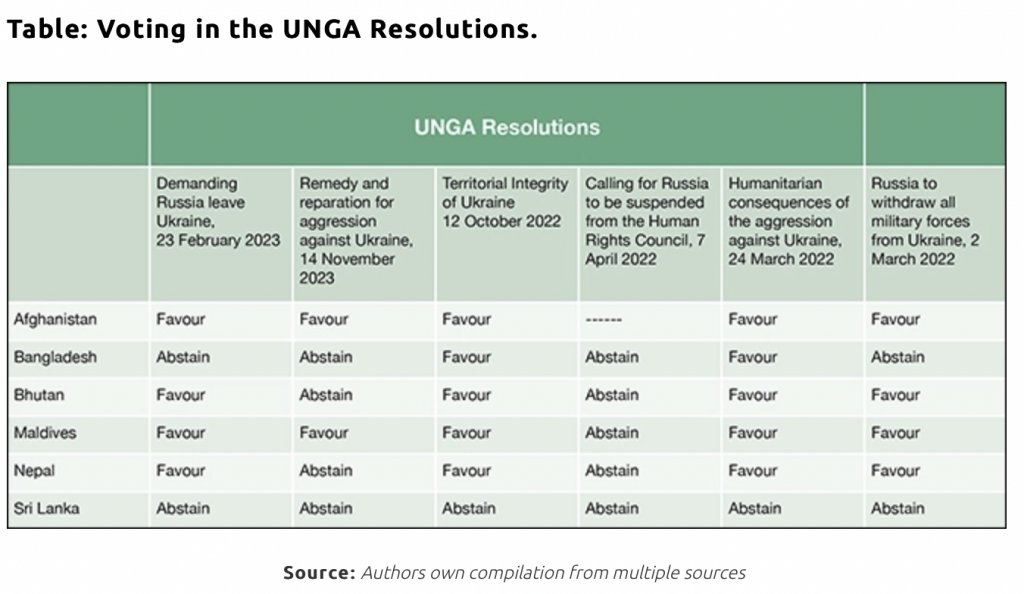

Accordingly, there is a clear divide between those who remained neutral and those who were unequivocal in their opposition to Russia. This article analyses the positions taken by six South Asian countries (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, the Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka) and looks at how history has coloured the current responses of these countries to the ongoing crisis in Ukraine.

The Soviet spectre in South Asia

The Soviet Union began rapidly expanding its relations with South Asia in the mid-1950s, positioning itself as a neutral, uncritical ally of non-aligned nations. The growing rift between Communist China and Soviet Russia likely played a role, as Moscow looked elsewhere in Asia for trusted partners. The shift in Moscow’s South Asia policy was accompanied by an uptick in Soviet contributions to UN programmes, and between 1953 and 1956, the Soviets contributed US$ 4 million (approx. US$ 42 million today) in funds. From the 1960s till the 1980s, the USSR provided economic aid to Sri Lanka andPakistan, and mediated the signing of an accord, the Tashkent Declaration, between India and Pakistan in 1966.

Arguably, South Asian countries’ response to the current crisis is driven by a balancing act between history and present national interest. Of the six South Asian countries, Afghanistan and Sri Lanka have embraced neutrality as their official position in this conflict. The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, following what it calls ‘its foreign policy of neutrality’ has asked both Russia and Ukraine to resolve the crisis through dialogue and peaceful means. Sri Lanka called dialogue and diplomacy a way forward to maintain peace and security. For Colombo, both Russia and Ukraine are important sources of its forex generation accounting for 2 percent and 2.2 percent of Sri Lanka’s imports and exports in 2020. The major imports from these countries to Sri Lanka include food grains, iron, etc., while the major export to both Ukraine and Russia is black tea. They are also among the top 10 countries contributing to Sri Lanka’s total tourist inflow. The fallout of the crisis is being felt deeply in Sri Lanka, compounding fuel and food shortages, a downward spiralling economy, and high inflation.

Bangladesh has embraced an unofficial policy of neutrality. Dhaka abstained from the UN resolution and has called on both parties to use peaceful means to resolve the crisis. This follows from its policy of maintaining distance from great power competitions on one hand and keeping its diplomatic space open for dialogue based on the idea of “friendship towards all, malice towards none”.

Bangladesh’s response to the Ukraine crisis was a diplomatic continuation of its long-term policy. Dhaka also shares historical ties with the USSR:Tthe Soviet Union not only extended support to India and Bangladesh during the 1971 War but also vetoed US-backed resolutions for immediate ceasefire and withdrawal of troops. In the post-Cold War period, Russia important development partner for Bangladesh, cooperating in sectors such as energy, infrastructure, etc. It is also important to note that Dhaka’s abstentions can be seen in light of its ambivalent relations with the US. Washington, during the 1971 War, had sent its naval task force to the Bay of Bengal in support of Pakistan. More recently, the US government imposed sanctions on Rapid Action Battalion, a paramilitary force deployed against the jihadi groups, for human rights violations, increasing tensions between Bangladesh and US.

Nepal, Bhutan, and Maldives share limited relations with Russia and Ukraine. However, their relations with Russia are still at a higher level than with Kiev. For Nepal, Russia has provided helicopters, investments, and humanitarian aid. With Bhutan and Maldives, it is the tourism sector that benefits from Russia. Nepal has been critical of Russia’s actions since the crisis began and has called out Moscow for using force against Ukraine and violating the United Nations charter. While Nepal has been critical of Russia, Bhutan has chosen to highlight the impact of the crisis on small states and the importance of upholding the values and principles of the UN. This was made clear at the UNGA where its Permanent Representative said that “Bhutan, 1000 miles away from the conflict, can feel the reverberation of the conflict” For its part, the Maldives had asked both parties to seek peace and political solutions. The responses of these countries against Russia appear to be a product of their geographical location and the geopolitical anxieties emerging from the push and pull of power competition in the region.

These countries have, more and less, been consistent in their voting patterns in the UN. They present an insight into their respective foreign policy decision-making, highlighting the interconnectedness of geopolitics and economic reasons. The voting pattern highlights a shift in the geopolitical landscape in the region and the increasing concern of these countries losing their foreign policy autonomy to power competition.

Past as prologue

The irony of the present situation is that the South Asian response is guided by the legacy of their relations with the USSR. Yet Ukraine was once geographically a part of the USSR as well, and can equally lay claim to this legacy. Ukrainians supported their efforts, such as in the case of Bangladesh, a fact that seems to have been lost in the narrative. In this sense, although the conflict is between Ukraine and Russia, it is viewed through a Cold War lens. Ultimately, and tragically, Ukrainian autonomy is lost to the burden of history.

The process of building a national narrative of geographic and historical continuity, in other words laying claim to not just territories but also time, affects how countries interact with each other in the present. Esoteric as this may sound, this idea is critical in understanding the divergence in how South Asia has responded to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. However, it also points to the fact that the region recognises the inevitability of being drawn into great power competition. The Ukraine crisis might have brought US and Russia competition to the forefront, but the major concern for the countries of South Asia is growing US-China competition.

Therefore, South Asian nations will try to incorporate the lessons of the Cold War and the Ukraine crisis along with their respective national interests as they chart their responses to the emerging competition in the region. In this regard, the support for Russia can be seen—not as the support for its actions but rather for what it once represented.

Source: This article was published by Observer Research Foundation