China’s ADIZ Over South China Sea: Whole, Partial Or None – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Felix K. Chang*

Ever since China declared an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) over the East China Sea in late 2013, many wondered whether China would do the same over its claims in the South China Sea. Early this year, the United States began to publicly warn China that it would not recognize a Chinese ADIZ over the South China Sea. Given the timing of its admonition, Washington seemed like it was preparing for a Chinese reaction to a ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration on a Philippine case against China’s South China Sea claims, which is expected in May.

China’s declaration of an ADIZ over the East China Sea caught many off guard. Perhaps to prevent a recurrence, the United States chose to signal China in advance. Naturally, China’s defense ministry retorted that Beijing had every right to establish an ADIZ over the South China Sea. After all, Beijing considers the area within its “nine-dash line” claim to be sovereign Chinese territory. Yet the ministry’s spokesman was quick to add that China had no plans to set up such an ADIZ.[1]

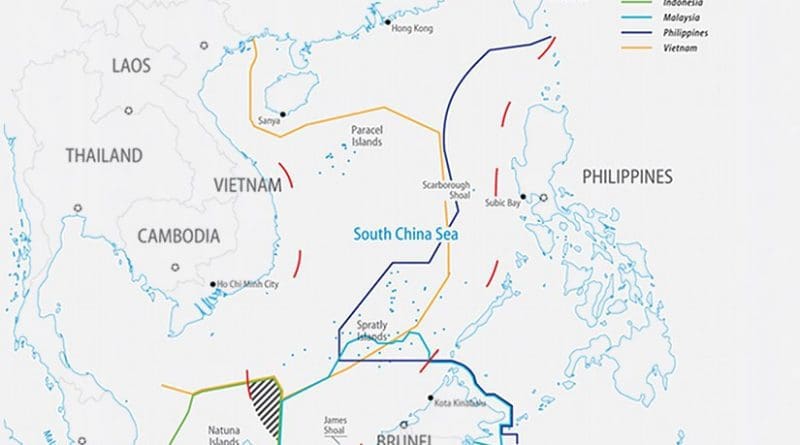

Apart from placating the United States, there are other reasons why China might hold off from establishing an ADIZ over the South China Sea. They deal with Malaysia and Indonesia, two of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (ASEAN) most influential members. Whereas China’s ADIZ over the East China Sea could narrowly target Japan, a Chinese ADIZ over the South China Sea would impact not only China’s two main antagonists there, namely the Philippines and Vietnam, but also all of the other disputants in the region, including Malaysia and Indonesia.

For decades, Malaysia has played down its dispute with China over the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea. Rather than confront China, as the Philippines and Vietnam have, Malaysia has tried to use quiet diplomacy to persuade China of the benefits of a multilateral resolution to the region’s conflicting claims. That strategy reached its high point in 2002 when China signed ASEAN’s non-binding declaration of conduct in the South China Sea. Although China has since violated the declaration’s terms, Malaysia has stuck to its strategy. Even after China twice held amphibious exercises off Malaysian-claimed James Shoal, only 80 km from Malaysia’s coast, Malaysia chose not to escalate tensions with China.

Similarly, Indonesia has minimized its dispute with China. So much so that Indonesian diplomats routinely repeat that their country has no territorial dispute with China. Though technically true—the two countries have no land features in dispute—what they do have is a maritime dispute. China’s nine-dash line claim encompasses some of Indonesia’s richest offshore oil and natural gas fields. (See hatched area on map.) Plus, China has increasingly made its presence known in the area. Just last month, two Chinese coast guard vessels again clashed with an Indonesian fishing boat. Such incidents have alarmed the Indonesian military. But Jakarta has hesitated from providing it with the resources needed to strengthen its defenses near the Natuna Islands.

A Chinese ADIZ over the whole South China Sea would definitely infringe on the claims of both Malaysia and Indonesia. That would be difficult for China to explain away. It would also run counter to China’s long-time strategy in the South China Sea. For years, China has sought to divide its Southeast Asian opponents and convince them to individually settle their disputes with it. A Chinese ADIZ over the whole South China Sea does little to achieve those ends. Rather, it could do the opposite. It would put Malaysia and Indonesia in the same boat as the Philippines and Vietnam, pushing them together. Moreover, such an ADIZ would undercut those who believe that by taking a less combative approach toward China their countries can avoid its assertiveness in the region.

On the other hand, if China declared an ADIZ over the northern half of the South China Sea—overlapping only the claims of the Philippines and Vietnam—it could reasonably argue that its aim was only to protect itself from airborne intrusions from those two countries. Both are building stronger air forces to counter China. That would at least encourage some in Malaysia and Indonesia. Still, a partial Chinese ADIZ would likely make many others uneasy that China could someday extend its ADIZ further.

Given the potential for an ADIZ (whether whole or partial) to unify ASEAN’s core states against it, China has good reason to be cautious. Ultimately, a Chinese ADIZ could create more problems for China than it solves. It could push Malaysia off the fence or turn Indonesia into a full-fledged disputant. It could also make it harder for surrounding countries, like Australia and Japan, to give China the benefit of the doubt. Finally, it would likely undermine the goodwill that China has been trying to generate across Southeast Asia through its “One Belt, One Road” initiative.

More broadly, a Chinese ADIZ over the South China Sea would mark a real change in China’s approach to not only its maritime dispute, but also East Asia. It means that China has become confident enough to act, regardless of the international consequences. If so, China will have indeed stood up. But it might learn that standing up can expose one to stiffer headwinds.

About the author:

*Felix K. Chang is a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. He is also the Chief Strategy Officer of DecisionQ, a predictive analytics company in the national security and healthcare industries. He has worked with a number of digital, consumer services, and renewable energy entrepreneurs for years. He was previously a consultant in Booz Allen Hamilton’s Strategy and Organization practice; among his clients were the U.S. Department of Energy, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Department of the Treasury, and other agencies. Earlier, he served as a senior planner and an intelligence officer in the U.S. Department of Defense and a business advisor at Mobil Oil Corporation, where he dealt with strategic planning for upstream and midstream investments throughout Asia and Africa.

Source:

This article was published by FPRI

Notes:

[1] “China says no need to ‘gesticulate’ over South China Sea plans,” Reuters, Mar. 31, 2016.

Time to get real, which Chang does not seem to want to do. China is the hegemon in Asia; its increasing strength economically/militarily comes at least partly from the fact that the US Congress in its collective brilliance saw fit to transfer most US manufacturing jobs to China, all the while going heavily into debt to the Chinese. China is also the linchpin in the BRICS system, now poised to dislodge the dollar as Int. Reserve Currency and to offer bilateral trading arrangements not dependent upon the US or the dollar. We are not that far away from Huntington’s early analysis in “Clash of Civilizations” that all would depend upon whether the US decided to confront China or to “bandwagon” it, as the Brits did with the US after WWII. I doubt very much that China will be dislodged from the East or South China Sea by the insignificant powers that contest possession: the resources are too important. Will the US, then, “confront” China over these territorial waters and their resources? It looks to me as though Obama’s “pivot to Asia” indicates that it will, especially because the US is now urging Japan to rearm and because it continues to hang on to S. Korea. Malaysia, the Philippines etc. will do what they’re told to do by the boss. The nonsense the US is putting out about “freedom of navigation” in the area will cut no ice with the Chinese. It is window dressing for the propaganda mills. The world is now so close to WWIII it would behoove everyone to act with caution unless WWIII is really what the elites are aiming for.