China’s Nuclear Interest In The South China Sea – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Felix K. Chang*

(FPRI) — Economic and sovereignty interests are commonly cited as the reasons for China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea. The security of China’s sea-based nuclear deterrent could be added to that list of reasons.

Since the founding of the People’s Republic, China has worried about external threats—and justifiably so. During the Cold War, it faced down both the world’s superpowers, first the United States and then the Soviet Union. Both were armed with nuclear weapons at a time when China was still developing its own arsenal.

But even after it successfully produced nuclear-armed ballistic missiles, China could not rest easy. It still had to ensure their survivability to create a credible nuclear deterrent.

China’s Sea-Based Nuclear Deterrent

Early on, China understood that ballistic missiles based on land would be more vulnerable to preemptive attack than those based under the sea. And the longer they could stay under the sea, the safer they would be. Thus, in the late 1950s, China began to acquire the technology needed for nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBN), which can operate underwater for long periods, and for their associated submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBM).[1]

By the 1980s, China built its first SSBN, the Type 092 (or Xia-class), along with its first SLBM, the JL-1. Though only one Xia-class submarine ever became fully operational, China went to great lengths to protect it. Chinese engineers tunneled under a rocky promontory at Jianggezhuang, adjacent to the Yellow Sea, to provide the submarine with a hardened shelter. As it turned out, the Xia rarely went to sea during its service life.[2] But if it sailed into the Yellow Sea today, China might have some cause for concern, given the proximity of capable naval forces from Japan, South Korea, and the United States on the sea’s eastern edge.

China’s Southern Strategy

After the Cold War, China continued to improve its sea-based nuclear deterrent. About a decade ago, China began serial production of its second SSBN, the Type 094 (or Jin-class). So far, the Chinese navy has commissioned four Jin-class submarines; the completion of the JL-2 SLBM followed.[3] But years before the submarines entered service, China had already started construction on a new naval base for them that runs along Yalong Bay, near the South China Sea. With satellite imagery, one can see the grand scale of the new base. (See image below.) It even features a submarine tunnel, like the one at Jianggezhuang, but with enough room for loading facilities and multiple submarines.[4]

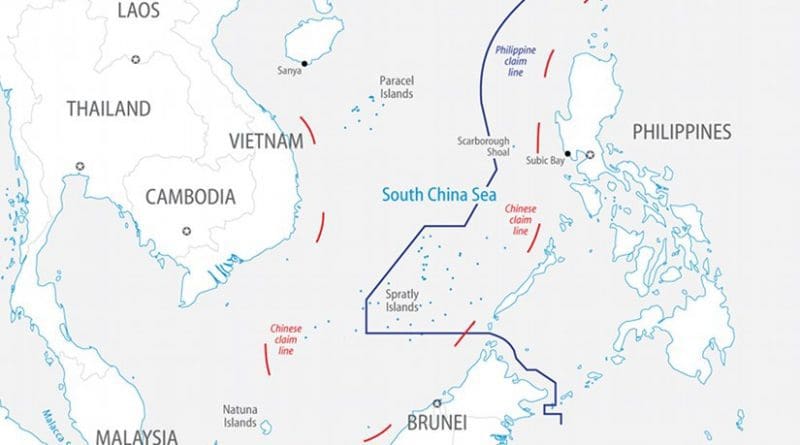

China’s Jin-class SSBNs are now regularly seen at the base. (See image below.) South of it is the South China Sea—a region increasingly dotted with Chinese military outposts and airfields. It is also a region with no navies capable of directly challenging China’s. Indeed, Chinese strategists may have envisioned the South China Sea to be a naval bastion, a partially enclosed area where China’s SSBNs could safely operate under the protection of friendly air and naval forces. The Soviet navy operated in the Barents Sea and the Sea of Okhotsk in much the same way during the Cold War.

To be sure, the South China Sea carries drawbacks as a naval bastion. The biggest is probably the fact that operating there would put China’s SSBNs further from potential targets in the Western Hemisphere, though future SLBMs may have longer ranges. Still, the South China Sea does enable China to disperse more widely its undersea nuclear forces, and thereby improve their survivability. If China has come to see the South China Sea as important to the security of its sea-based nuclear deterrent, then those who hope that patient economic and diplomatic engagement will persuade China to change its behavior in the region are very likely to be disappointed, as they have been to date.

About the author:

*Felix K. Chang is a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. He is also the Chief Strategy Officer of DecisionQ, a predictive analytics company in the national security and healthcare industries. He has worked with a number of digital, consumer services, and renewable energy entrepreneurs for years. He was previously a consultant in Booz Allen Hamilton’s Strategy and Organization practice; among his clients were the U.S. Department of Energy, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Department of the Treasury, and other agencies.

Source:

This article was published by FPRI.

Notes:

[1] John Wilson Lewis and Xue Litai, China’s Strategic Seapower: The Politics of Force Modernization in the Nuclear Age (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994), pp. 23–125, 129–205.

[2] Stephen Saunders, ed., Jane’s Fighting Ships 2014-2015 (London: Jane’s Information Group, 2014), p. 128.

[3] Office of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2016 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Defense, Apr. 2016), p. 26.

[4] Richard D. Fisher, Jr., “Secret Sanya: China’s new nuclear naval base revealed,” Jane’s Intelligence Review, May 2008, pp. 50–53.