Identity History: Austronesian Asia? – Analysis

The region known as Maritime Southeast Asia may be better defined by terms that acknowledge the culture, history and global prominence.

By Philip Bowring*

Austronesian Asia? Nusantaria? These are not familiar terms. Yet they define the common bonds of some 400 million people whose ancestors for several millennia occupied the islands and nearby coasts more commonly known as “Maritime Southeast Asia.” These terms now cover most of Indonesia, the Philippines and Malaysia and once included Taiwan and much of the coast of Vietnam with old links across the Indian Ocean to Madagascar. This is a region with its own identity separate from mainland Asia.

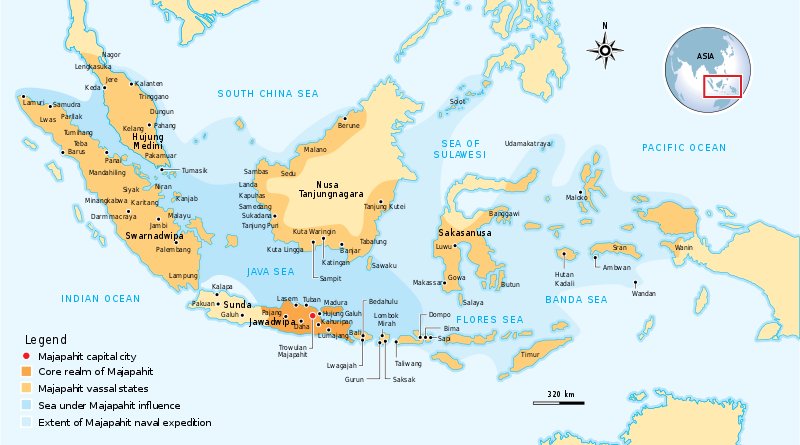

“Maritime Southeast Asia” is a recent, western-derived geographical term linked to neither culture nor history. Austronesian Asia on the other hand defines the language group into which all the region’s major languages fall – Malay, Javanese, Tagalog, Visayan and many local variations. Nusantaria is an extension of “Nusantara,” the Sanskrit term used to describe the island realm of the Java-based Majapahit Empire and in modern Malay refers to the Indonesian archipelago. Today it includes the Philippines and has historic links to Taiwan, Vietnam, the Marianas and Madagascar.

This region has many characteristics which set it apart from mainland Asia and have provided it with a common identity. Today this identity is more often than not submerged by national focus on recently created modern states, or on religious divides created by the rival, imported Semitic religions, Christianity and Islam, which now predominate. But the identity is never far below the surface.

It is no accident that Indonesians and Filipinos comprise a large proportion of the seamen aboard many of today’s merchant fleets. The sea has defined the region since the melt at the end of the last Ice Age, more than 20,000 years ago, when rising seas created most of its major islands. Sumatra, Java, Borneo, Palawan and Taiwan were previously joined to the Eurasian mainland. People perforce became seamen, living on boats and learning the arts of boat-building and navigation. Thus did Austronesian languages and cultural norms carried by the original migrants from Africa spread around the Asian archipelago and across the Pacific and Indian oceans. Trade was also inseparable from sailing.

By the beginning of the current era, India and the archipelago had established trade links while the Roman trade with India, based out of Alexandria in Egypt and via the Red Sea was booming. Greek geographer Ptolemy had a roughly accurate idea of the Malay Peninsula and the first Romans to reach China did so by sea, and not by the much over-hyped Silk Road land route. Indians were seen in Alexandria, and Romans described as “rafts” the boats with outriggers from the archipelago.

Trade with India brought Hinduism and Buddhism to the archipelago, the Malay Peninsula and the Cham region of coastal Vietnam, and with it writing and more developed governance systems. The Melaka strait became the crucial waterway in trade between China and the archipelago to India, Persia and Arabia, leading to the rise of port states of which the most important was Sri Vijaya, based at modern Palembang in Sumatra. It was also a center of Buddhist learning. A Chinese monk visiting in the 8th century noted a city with a thousand monks.

Sri Vijaya created a trading empire of lesser ports and had a dynastic alliance with the Mataram Kingdom of central Java, extending Malay and Javanese influence across the region touching Manila Bay and northeast Mindanao in the Philippines. A 10th century Arabic account described the Sri Vijayan capital as one where parrots spoke many languages including Arabic, Persian and Greek

Booming trade driven by the prosperity of China’s Tang dynasty and the Baghdad-based Abbasid empire saw the construction of the great temples of Borobudur (Buddhist) and Prambanan (Hindu) in Java. Guangzhou, the center of China’s maritime trade, was thronged with foreigners, Arab, Persian, Tamil, Malay and many more. People from the archipelago had already begun settlements far away across the Indian Ocean in Madagascar, but these grew significantly and ships from Java and Sumatra were more than occasional visitors to the coasts of Yemen and east Africa.

Much of the trade had always been driven by Chinese demand and supply, but only in the later Song dynasty did Chinese merchants begin to play a role in the sea trade, and even then a minor one. The first clear political intervention in the seas to China’s south and west occurred in the late 13th century when the Mongol overlord of China sent ships demanding fealty to the emperor in Beijing. The king of east Java refused. The Chinese invaded and were defeated.

Java flourished; the east Java-based Majapahit empire loosely controlled lands from the Malukus to north Sumatra. Huge Javanese ships, which greatly impressed Chinese visitors, traded across the region and Indian Ocean. Then came the early 15th century voyages of the renowned Ming dynasty Chinese commander, Zheng He, a Muslim eunuch from a conquered region in western China. His seven voyages with a huge fleet around the southern seas and to the coasts of Africa and the Red Sea received much acclaim – largely from accounts in Chinese official annals.

These voyages showed off Chinese power with many small states persuaded to send envoys acknowledging the supremacy of the emperor in Beijing. But the voyages were costly and of scant value, ending after 30 years. They left limited marks, the most significant favoring Melaka which became the region’s premier port. Melaka’s prestige as a Malay and Muslim center helped speed the spread of Islam, already well established in some ports in Sumatra, across much of the archipelago. New sultanates emerged in Java created by Muslim traders from many locations, and 1478 saw the conquest of the Majapahit kingdom by the north Java port sultanate of Demak.

Just 80 years after Zheng He’s last voyage, Melaka was captured by the Portuguese. The first European intruders into the region saw Melaka as key to the lucrative Asia-Europe spice trade putting a Portuguese hand on the throat of the merchants of Cairo and Venice. Indeed, for a 100 years the Portuguese dominated this trade, from which the ports and sultanates of the region mostly benefited. But profits drew rivals, the Dutch in particular, then the English. Thus from the 17th century began, in fits and starts, 300 years of gradually increasing European commercial and then political power, reaching its apogee around 1900.

Creeping western imperialism saw the gradual undermining of the old local states and the takeover of commerce by Europeans and then also by immigrant Chinese. They arrived in large numbers, particularly in the 19th century, as labor for the mines and plantations were needed to fuel the industrial revolution in the west.

Post-1945 political independence of new nation states provided a new basis for prosperity and, briefly, an idea for a federation of Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia – a MAPHILINDO. But nation-building priorities and religious differences were obstacles to a broader sense of identity, let alone federation. States have mostly prospered, but have been heavily reliant on foreign and non-indigenous capital. Yet the post-1945 era is still a brief time in the context of the millennia of history of Austronesian Asia.

*Philip Bowring is a journalist who has been based in Asia since 1973. He lives in Hong Kong, dividing his time between writing columns, books and helping develop Asia Sentinel, a news and analysis website. This essay is based on his book Empire of the Winds: The Global Role of Asia’s Great Archipelago , Bloomsbury Publishing. Read an excerpt.