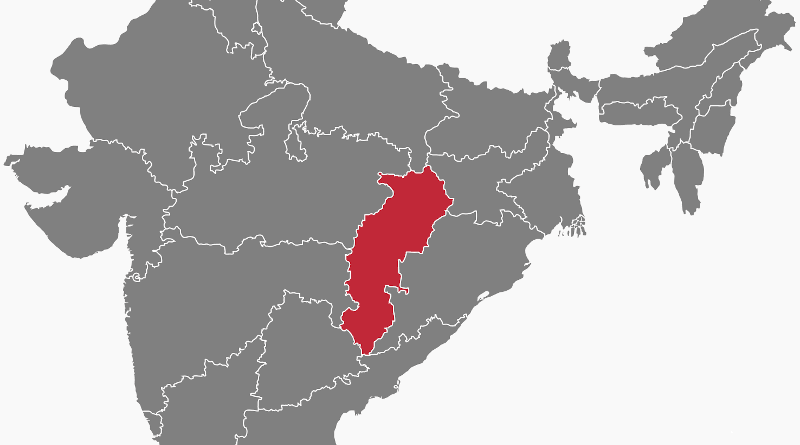

India: No Tears For Salwa Judum In Chhattisgarh – Analysis

While the civil society’s argument appeared to have prevailed in the first round, the Chhattisgarh government is making a concerted effort to win round two. Following the July 5 Supreme Court (SC) decision disbanding the anti-Maoist vigilante movement, Salwa Judum, the Raman Singh government has taken a decision to lower the recruitment benchmark so that the Special Police Officers (SPOs), facing a purge, can be recruited into the regular police force. Neither was the Salwa Judum movement the brightest of counter-insurgency ideas, nor will the sly attempt to circumvent the apex court’s decision add to the state’s capacity to deal with the extremists.

In spite of the criticism the SC decision has received from the security experts, it is fair to say that the Salwa Judum movement, in its half-decade- long existence, added in no significant manner to the counter-Maoist capacities of the state. It merely economised the security architecture by hiring SPOs who were paid a meagrely

Rs 3,000 per month. It created a smokescreen of popular discontentment against the Maoists in the tribal areas, even as the SPOs did their best to alienate the tribal population further from the state. Chhattisgarh’s overdependence on the Salwa Judum to track down the extremists, and the pitfalls such a strategy produced, defaced the state’s image in the eyes of the very population it was trying to win over to its side. SPOs brought in more harm to the anti-Maoist endeavours, than lending it a supporting hand.

Arguments have been made about the operational utility of the SPOs in counter-Maoist operations and how the SC has simply glossed over this important aspect while giving its ruling. The SPOs brought in local knowledge to the police department, which had lost all its ground level contact. No doubt, such arguments have some validity. However, at the same time, these rather less cumbersome ways of accessing ground level intelligence also acted as a de-motivating factor for the police establishment. The painstaking tasks of re-establishing police control over the Maoist-dominated areas, as a result, received less attention.

Strange it may appear, but Chhattisgarh police department continued to have 11 per cent vacancy rate in its armed police segment, but went on to recruit over 4,500 SPOs. Over 1,000 posts below the ASI level remained vacant, thereby depriving the state of the services of men critical for ground- level intelligence and operations. Interestingly, resource crunch was not a factor for the enduring vacancy. Report of the Comptroller and Auditor-General of India, for the year ending March 2009, indicates that Chhattisgarh failed to spend almost Rs 54 crore, amounting to 20 per cent of its allocated funds for police modernisation. Available money remained unspent even as almost 23 per cent of the weapons in possession with its personnel were obsolete. In addition, there was shortage of light vehicles in the police stations and despite availability of funds, large numbers of residential and non-residential buildings were not completed. The continuation of the SPO experiment clearly had become more of a prestige issue for the state government, rather than an indispensable operational issue.

In this background, the latest decision in Raipur to bring down the educational as well as physical attributes of candidates for recruitment as police constables represents the persistence of a dogmatic mind, completely insincere to the creation of a new generation police force. Despite the rather well-known problems currently afflicting the poorly literate Afghan National Security Force in that country, the Chhattisgarh government is unveiling a scenario of creating a huge mass of ‘dud soldiers’ in its police force. Needless to say that the objective of police modernisation is dying a premature death in Chhattisgarh. The state needs to address the chronic problems of lack of inter-state coordination, provision of better arms and facilities for its existing police personnel and focus on the creation of a competent force that would not only take on the military might of the Maoists, but any other exigency that would arise in future. The sudden unavailability of a vigilante force is a relatively minor issue.

Former home secretary G K Pillai on the day of his retirement had let out a harsh reality. The counter-Maoist efforts need to be continued for at least five to seven years, before a turnaround is achieved. This needs to be factored into the policies of police establishments of each state. The security force operations against the Maoists need to be sincere, unrelenting and fair. There are no shortcuts to success.

This article was published in New Indian Express, 31 July 2011 and reprinted with permission