Winds Of Change In Antarctica: Beyond Global Warming Issues – Analysis

By K.M. Seethi

Our prevalent maps are elegant, highly detailed, and generally sufficient to forestall vertigo among the more privileged, but the dragons of the unknown world are no longer just decorous motifs in the margin. In fact, they increasingly suggest that it is becoming as futile to look for politics where it is supposed to be as it is to look for the sources of lasting authority down the barrel of a gun — (R.B.J. Walker,After the Globe, Before the World,New York: Routledge, 2010).

Writing on ‘security, sovereignty, and the challenge of world politics,’ International Relations scholar R.B.J. Walker noted: The dilemma before us seems obvious enough. Threats to people’s lives and well-being arise increasingly from processes that are worldwide in scope. The possibility of general nuclear war has been the most dramatic expression of our shared predicament, but potentially massive ecological disruptions and gross inequities generated by a global economy cause at least as much concern. Nevertheless, both the prevailing interpretations of what security can mean and the resources mobilized to put these interpretations into practice are fixed primarily in relation to the military requirements of supposedly sovereign states. We are faced, in short, with demands for some sort of world security, but have learned to think and act only in terms of the security of states.

After 32 years of Walker’s observations, the world is still grappling with the problematic concerns of the ‘universal-particular’ locales of security. Meanwhile, the world system has witnessed cataclysmic changes—from the disintegration of the Soviet bloc, the Gulf war, the pronouncement of a post-cold war ‘new world order,’ frenzied drive towards globalization, the emergence of a world trade regime, the 9/11 attacks, world economic meltdown, the ‘Arab spring’ to the pandemic and the Ukraine war. All these years, scholars were also debating whether the world had entered into a ‘unipolar’ ‘multipolar’ or ‘tripolar’ world, locating the actual fulcrum of global power relations. However, amid these ‘polar’ debates, not much attention has been paid to the deepening engagements of the major powers in the Earth’s Polar regions—the Arctic and Antarctica. These two regions are critically significant from the point of view of global environmental security—in terms of their deeper impact on the global ecosystem. Added to this scenario is the growing geopolitical dimension of the major powers’ Polar engagements.

Poles Apart, Yet Analogous Issues

The Arctic and Antarctica are rich repositories of the planet’s fresh water as ice. Alas, in both the Arctic and parts of the Antarctic, ice is melting at a disturbing frequency, and the world has already witnessed a lot of Antarctic glaciers receding in the last century. There are reports that in the Antarctic peninsula, almost 90% of glaciers on the westside are declining and the primary reason is warming ocean temperatures.

While the Polar regions play a vital role in the conditioning of the world’s climate, the principal actors of international relations are also ‘worried’ about their role in sustaining ‘other’ interests in these regions. It’s because these regions are also rich repositories of oil, minerals, and marine wealth. But a problem for these nations is the limits set by international regulatory regimes for their ‘territorial rights’ and ‘sovereignty’ across the Polar regions. While there are no permanent inhabitants in Antarctica, nearly four million people have been living in the Arctic regions for centuries and almost 10% of them are indigenous communities—eking out their livelihood through hunting, fishing, and making clothing in extreme weather conditions. The scenario in Antarctica is different. While there are no settled communities in Antarctica, thousands of tourists visit the region every month, and hundreds of scientists from different parts of the world stay in different research stations intermittently. However, Antarctica has a much wider geopolitical significance today with more and more countries staking their varied claims with covert and overt operations.

Antarctica Inspires, Yet Too Many Ill-Winds?

Geologically divided into three different parts—East Antarctica, West Antarctica, and the Antarctic Peninsula—the continent has varied tectonic accounts as manifested in the monitored topographic and geological regions. Even as scientists get deeply engaged in studies and research, Antarctica excites people of all ages and the 14.2 million km2 landscape of the southernmost continent is filled with a bounty of wonders. Andrew Denton, an Australian award-winning writer, performer, and producer famously said: “If Antarctica were music it would be Mozart. Art, and it would be Michelangelo. Literature, and it would be Shakespeare. And yet it is something even greater; the only place on earth that is still as it should be. May we never tame it.” According to Elizabeth Leane, who wrote a chapter in Routledge handbook volume—The Antarctic in literature and the popular imagination—“creative responses to the Antarctic have tended to come in waves, responding to particular historical events: expeditions, discoveries, adventures, tragedies, controversies.”

The Greek philosopher and political theorist Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E.) was one of the first intellectual minds to think about the systems of existence—from the State to the Earth—more empirically, rather than imaginatively. He made critical observations about geological changes and was perhaps the first to develop an evidence-based idea regarding the physical changes on the earth. Known for his interest in classification and comparative analysis, Aristotle understood that the surface of the earth had characteristics that are transient. His work Meteorologywould not have captured the imagination of many, yet he hypothesized that the southern hemisphere must have a landmass large enough to balance the lands in the northern hemisphere. He called the probable but undiscovered landmass ‘Antarktikos,’ meaning the opposite of the Arctic. Aristotle’s comments in Meteorologymerit our attention today, after 2000 years. He writes:

There are two inhabitable sections of the earth: one near our upper, or nothern pole, the other near the other or southern pole; and their shape is like that of a tambourine. If you draw lines from the centre of the earth they cut out a drum-shaped figure. The lines form two cones; the base of the one is the tropic, of the other the ever visible circle, their vertex is at the centre of the earth. Two other cones towards the south pole give corresponding segments of the earth. These sections alone are habitable. Beyond the tropics no one can live: for there the shade would not fall to the north, whereas the earth is known to be uninhabitable before the sun is in the zenith or the shade is thrown to the south: and the regions below the Bear are uninhabitable because of the cold.

Now since there must be a region bearing the same relation to the southern pole as the place we live in bears to our pole, it will clearly correspond in the ordering of its winds as well as in other things. So just as we have a north wind here, they must have a corresponding wind from the antarctic. This wind cannot reach us since our own north wind is like a land breeze and does not even reach the limits of the region we live in. The prevalence of north winds here is due to our lying near the north. Yet even here they give out and fail to penetrate far: in the southern sea beyond Libya east and west winds are always blowing alternately, like north and south winds with us. So it is clear that the south wind is not the wind that blows from the south pole. It is neither that nor the wind from the winter tropic. For symmetry would require another wind blowing from the summer tropic, which there is not, since we know that only one wind blows from that quarter. So the south wind clearly blows from the torrid region. Now the sun is so near to that region that it has no water, or snow which might melt and cause Etesiae. But because that place is far more extensive and open the south wind is greater and stronger and warmer than the north and penetrates farther to the north than the north wind does to the south.

Why Aristotle today? It’s because several scientific studies of our contemporary times address the ‘question of winds’ in Polar regions which Aristotle dwelt upon differently, centuries back. For example, A team of scientists in the U.S. and the U.K. found that global warming has triggered a shift in wind patterns that are eventually bringing more warm ocean water into contact with the region’s ice. They discovered that wind patterns evidently changed over the past century—and perhaps that can account for the intensified melting of the West Antarctic ice sheet. “In the 1920s, the team reports, the winds over the Amundsen Sea would have predominantly blown toward the west, mostly keeping the warm ocean water at bay. But today the wind patterns flip-flop between blowing eastward and westward. When the waters blow toward the east, the deep layer of warm ocean water can creep in.” According to Paul Holland, an ice-ocean scientist at the British Antarctic Survey, “When the wind blows east, you get these rivers of warm water coming into the [Amundsen Sea] and melting the ice…It’s basically like turning on a hot tap when the wind blows toward the east and turning off the tap when the wind blows toward the west.” Holland further acknowledges that the “reason climate change is causing this shift is because of the fundamental way wind works on the earth and responds to warming.”

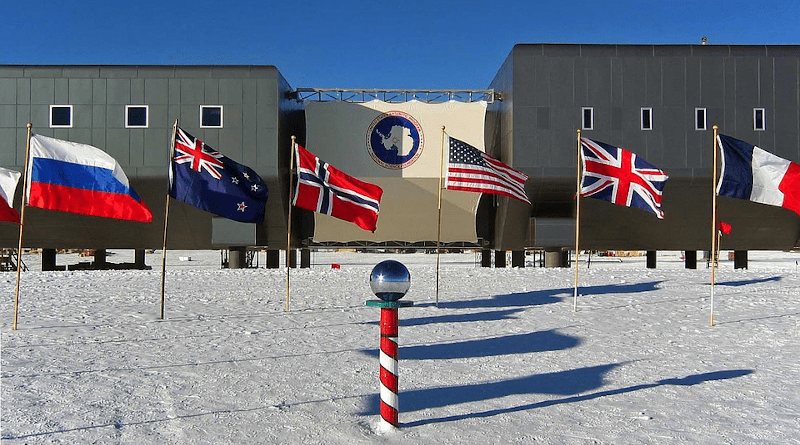

A great deal of scientific effort gets underway focussing on these changes and challenges in the Antarctic region. As many as 30 countries have research stations in Antarctica where scientists investigate global environmental issues like climate change and sustainable management of marine ecosystem. While the scientific community across the world have high stakes in such studies, the major powers are no longer reluctant to keep their ‘strategic interests’ under wraps.

Beyond Claims, Beneath Stakes

A Congressional Research Service Report (CRS) in 2021 acknowledged that an increasing global attention on Antarctica and the Southern Ocean emerged from the geopolitical and environmental developments. The argument has it that “these developments may have political, economic, and security implications” for the world. The CRS Report specifically pointed out Washington’s ‘geopolitical concerns’ over growing engagements of China and Russia in the Antarctic. The Report mentioned that during the Trump Administration a presidential memorandum was issued, stating that the United States would require “a fleet of polar security icebreakers that are tested and deployable by 2029 to protect national interests in the Arctic and Antarctic regions.” It was also mentioned that the Congress had shown interest in Antarctica “through legislation under Title VII of the Securing American Leadership in Science and Technology Act of 2020… which would have addressed, in part, expeditions and tourism in Antarctica and environmental emergencies in the Antarctic ecosystem that result from such activities.” Though the Bill (US HR5685) was introduced in the 116th Congress and later referred to a House Sub Committee of the legislature on 30 October 2021, no further action has apparently been taken till date by the Biden administration. Its fate remains uncertain, oddly.

Meanwhile, a similar legislative measure has been introduced in Indian Parliament—Indian Antarctica Bill, 2022—with several features put in place by the Narendra Modi Government akin to the Bill introduced in the US Congress. In March 2022, the Government of India already announced its Arctic Policy. And the new legislation on the Antarctic, by all means, would reinforce its Polar policy regime. It further indicates the bonded strategic mindset between New Delhi and Washington that has today acquired a new meaning under the emerging global power dispensation. While sustaining the traditional strategic tie-up with Moscow, as it has been evident in the post-Ukraine war conditions, New Delhi does not hide its concerns over China and its increasing involvements in vital strategic locales, such as the Polar regions, South Asia, Central Asia, East Asia, South China Sea etc.

China’s Antarctic engagements started way back in 1983, when it ratified the Antarctic Treaty. It secured the consultative status in 1985 and has since increased its activities with the launching of several research stations: Great Wall on King George Island (1985); Zhongshan on Larsmann Hill (1989); Kunlun on Dome A, near the center of East Antarctica (2009); and Taishan on Princess Elizabeth Land (2014). Chinese President Xi Jinping announced that China was aspiring to become a “polar great power.” He said that to maintain this sort of leadership in the polar regions, “a state must have high levels of polar scientific capacity and scientific research funding, a significant presence, significant economic, military, political, and diplomatic capacity there, plus a high level of international engagement in polar governance.” China also entered into an agreement with Australia in 2014 with a view to deepening their Antarctic relationship. The agreement envisaged, among other things, China’s obligation to use Australia as an entryway to Antarctica. In 2017, China brought out its first white paper on its Antarctic explorations, “pledging to boost its capabilities in the exploration and study of the continent.” The paper noted that China would “build a new permanent station and advanced icebreakers, develop aerial capability for survey and transportation, and design scientific apparatuses for the Antarctic environment.” China hosted the 40th Antarctic Treaty meeting in Beijing. China also announced its Arctic policy in the following year, declaring itself as a ‘Near Arctic State’ with further indications of setting up a ‘Polar Silk Road.” Besides, China began its plans to build a fifth station on Inexpressible Island in Terra Nova Bay of the Ross Sea which is expected to be completed in 2022. China also set up its global satellite navigation system to increase its surveillance across the Antarctica. In 2019 China sent two icebreakers to the Antarctic in its most ambitious polar expedition. The Xuelong, or Snow Dragon was scheduled to meet another icebreaker, Xuelong II—the first Chinese-built vessel of its kind—at Zhongshan Station on Prydz Bay in East Antarctica in late November before the ships carry out separate missions in the region. This was the 36th official Antarctic expedition for China, and the first involving two research icebreakers.

Admittedly, China’s increasing engagements led to speculations that Beijing is bidding to reinforce its influence in the region. Concerns are also in place that China’s growing presence will eventually lead to a future territorial claim if the Antarctic Treaty is altered, if not rescinded. China’s deepening engagements in Antarctica are still viewed in the context of its “undeclared military activities and mineral exploration.” Scholars like Nengye Liu, however, content that China has only “limited capacity to advance its interests” in the Antarctica and cannot erode Antarctic Treaty for obvious reasons.

Like China, other countries are also increasing their footprints in the Antarctica. For instance, Russia started exploring offshore oil and gas potential off the coast of Antarctica. In early 2020, Russia undertook a major seismic survey in Antarctica. Russia’s state-run geological survey Rosgeologia, inspected coastal areas off Antarctica’s Queen Maud Land “to assess the offshore oil and gas potential of the area.” A report noted that Rosgeologia’s seismic surveys indicated that there would be, at least, 513 billion barrels of oil and gas equivalent in Antarctica. Obviously, such ‘findings’ would lead to, not only Russia but other major powers also, “set their sights on the world’s most underexplored continent.” In fact, Antarctic Treaty bans oil and gas exploration in and around Antarctica but allows for scientific research, which might include these activities. Some analysts note that Russia’s activities could be viewed as potentially destabilizing and might cause concern that Russia aims to claim oil and gas resources in the region when the ban on mineral extraction comes up for review in 2048. The issue may assume wider significance in future even as Australia, Chile, Argentina, Norway et al. also make territorial claims of the Antarctic region.

In fact, when the Antarctic Treaty was inked in 1959, the exploitation of resources was not a major point of discussion, perhaps to avoid any disruption of the process of finalising it. However, in the 1980s, the issues emerged seriously and led eventually to the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty(known as the Madrid Protocol). The Madrid Protocol put forth the principles under which environmental protection in Antarctica is to be regulated. This includes a ban on all commercial mining for at least fifty years.

The Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) consists of the main Treaty (1959), the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR 1980) and the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (Madrid Protocol 1991). The 1959 Treaty stipulates that Antarctica should be used “exclusively for peaceful purposes and shall not become the scene or object of international discord.” The cold war conditions made this Treaty very significant. In fact, the First Article itself pronounced this commitment—”There shall be prohibited, inter alia, any measures of a military nature, such as the establishment of military bases and fortifications, the carrying out of military manoeuvres, as well as the testing of any type of weapons.” Article IV further stated that all “nuclear explosions in Antarctica and the disposal there of radioactive waste material shall be prohibited.” CCAMLR seeks to ensure the “conservation of Antarctic marine living resources” and the “maintenance of the ecological relationships between harvested, dependent and related populations of Antarctic marine living resources and the restoration of depleted populations to the levels” which ensure its stable recruitment.

Howsoever significant the regulatory framework of the Antarctica governances is, the major powers have growing stakes in expanding their commercial undertakings in the Polar regions, alongside their scientific activities. This will definitely result in competition and rivalry on a wide range of issues amid concerns for environmental balance and ecosystem stability. The experience of the Arctic Council, in the wake of the Ukraine war, shows that the strategic fallout of any geopolitical games would have deleterious consequences for the planetary survival. If the freezing of the Arctic Council proceedings could be of any indication—as a punishment of Russia for its actions in Ukraine—the Antarctica is likely to be a potential arena of a similar rivalry given the geopolitical games underway alongside the ‘winds of change’ across the strategic locale.

This is precisely the warning that R.B.J. Walker sounded three decades back—the tragedy of prioritising state interests at the cost of universal or planetary security. Aristotle once insisted that phronesis is an indispensable virtue for statecraft. But who still remains committed to ‘practical wisdom’ in statecraft vis-à-vis global interests is a knotty question.

The author, an ICSSR Senior Fellow, is Academic Advisor to the International Centre for Polar Studies (ICPS) and Director, Inter University Centre for Social Science Research and Extension (IUCSSRE), Mahatma Gandhi University, Kerala.

An interesting piece on a territory that is poised for a global rivalry. Why is that a US domestic legislation on the Polar regions got disrupted, even as India succeeded ? India does not seem to have any ambitious military program in the Antarctic region, yet it must play a larger role in the Polar governance in the interest of humanity. The worst victims of climate change would be the countries in the Global South, and hence India should lead these nations towards a rule based order in both the Arctic and Antarctic regions. Let the big players understand that they cannot play dangerous games in such sensitive and vulnerable regions.

The major actors of the world actually go beyond ‘science diplomacy’ in the Polar regions, as both Arctic and Antarctic are ‘prospective’ territories for global accumulation. But, it would be a dangerous accumulation process for the planet, to say the least.