Jewish Music And Singing In Morocco – Analysis

Morocco, a country of multiculturalism/tamaghrabit (1)

Under the tree of Morocco which according to the late King Hassan II has roots deep in Africa, the trunk in the Arab-Muslim world, and the foliage in Europe, (2) all its children have their place in its umbrage. No matter their beliefs, their religions, their languages, or their history. They all contribute -Muslims, Christians, and Jews- to a heritage born of a plural history, which has combined cultures, lands, languages, and religions: a dynamic culturalism of tolerance, vivre-ensemble, and forgiveness. (3) Thus, multiculturalism refers to a cultural broth made of cultural practices: religious traditions, music, dance, art, etc.

Over the centuries, Morocco, a country whose roots have been irrigated by the streams of multiculturalism, has forged its own model in which everyone finds their place. A singularity inscribed in the fundamental law of the Kingdom and especially integrated into the collective consciousness of Moroccan society.

Few countries can boast of a national identity that is one and indivisible, a unity forged by the convergence of Arab-Islamic, and Amazigh components and which has been nourished and enriched by its African, Andalusian, Hebrew, and Mediterranean tributaries.

While in other countries, religion is used to divide and reject. In Morocco it is a social cement, and it has always been a factor of peace, love, communion, and togetherness. A philosophy and way of life that, moreover, are based on a solid foundation of the institution of the Commandership of the Believers “imârat al-mu’minîne“, not Commandership of Muslims, that unites Moroccans of different religious beliefs.

The love that Moroccans of the Jewish faith have for their country of origin all over the world shows that Judaism has never been alien to Morocco, on the contrary, it has for over more than two millennia been an integral part of the culture of the country and still is today, and in spite of the fact that Moroccan Jews have gone to Israel and elsewhere. More than that the Moroccans of the diaspora, Muslims, Jews, or even Christians, have always expressed strong love for their country of origin.

It is only in this land that the Moroccan Jewish community offers original perspectives on the interpretation of Jewish life in the land of Islam, unlike in other countries in the immediate and distant environment. Today, literature, history, traditions, dialect, gastronomy, music, streets, and walls in Fez, Sefrou, Debdou, Meknes, Essaouira, Casablanca, or Tinghir testify to a valuable presence that has lasted through time and is, undoubtedly, a test to time. Moroccan Jews have gone but their spirit remains grand in the spaces they left behind and, mainly, in the hearts. (4)

From the highest level of the State to the little people, through the different strata of society, the Jewish component has always had its place in the house of Morocco. (5)

Adopted in 2011, in the context of the Arab Spring, Morocco’s new Constitution recognizes the Hebrew component as part of the culture of the kingdom. The preamble states, quite clearly, that: (6)

’’A sovereign Muslim State, attached to its national unity and to its territorial integrity, the Kingdom of Morocco intends to preserve, in its plentitude and its diversity, its one and indivisible national identity. Its unity, is forged by the convergence of its ArabIslamist, Berber [amazighe] and Saharan-Hassanic [saharo-hassanie] components, nourished and enriched by its African, Andalusian, Hebraic and Mediterranean influences [affluents]. The preeminence accorded to the Muslim religion in the national reference is consistent with [va de pair] the attachment of the Moroccan people to the values of openness, of moderation, of tolerance and of dialog for mutual understanding between all the cultures and the civilizations of the world.’’

This legal document attests to a successful marriage of traditions, habits, and customs of different cultures: Amazigh, Arab-Muslim, Hassani, Jewish, Andalusian, Mediterranean, and African, giving Morocco a rich and diverse cultural heritage whereby each region has its own particularities contributing to enriching the Moroccan cultural legacy.

Moroccan Jewish music tradition

Since the Middle Ages, Jewish musical and poetic (7) practices in the Muslim West have evolved in line with Muslim practices and traditions of music (8) and poetry, which developed in the Hispanic-Muslim and Arab-Berber cultural areas. (9)

The reasons for this cultural complicity were numerous. The involvement of Jewish intellectual elites in Muslim cultural creation and even, at certain times, and under certain dynasties, their intervention in the management or proper support of the sovereign’s property, the case of tujjâr as-sultân, (10) or in the diplomacy of certain sovereigns, generated areas of common knowledge, transmission and cooperation, the repercussions of which are inscribed in the intense Jewish intellectual production, in the medieval times and later, both in medieval Judeo-Arabic and in Hebrew. (11)

On the other hand, the economic and professional coexistence of the two communities, whose complementarity was vital for the Jewish communities, also multiplied the opportunities for personal and cultural encounters between Jews and Muslims. These encounters resulted in the permanent borrowing of oral and musical traditions by Jewish amateurs and professionals, (12) who have integrated them into the cultural habitus of their community, while often giving them new social functions and semiotic values in accordance with canonical Jewish values and traditions. (13)

Centuries of living together inevitably leave their mark, except that it is not clear who marks who. The Jews of Morocco have always been part of the socio-economic and political landscape of the kingdom, without abandoning their own heritage, which has enriched the Arab-Muslim substratum of Morocco in the past and still does today indirectly though they have left the country. (14)

Moroccan-Jewish music is the result of the fusion of Moroccan and Andalusian cultures over time. With the development of the means of recording and the democratization of the vinyl, the music of the Jews of Morocco has spread worldwide and interpreters have emerged and risen to stardom.

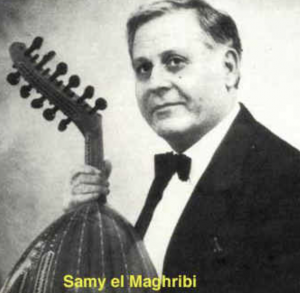

This is the case of Samy El Maghribi, whose real name is Salomon Amzallag, who is one of the pioneers of the Moroccan classical song. In the musical style of Moroccan Shcabî (popular music) the singer Raymonde El Bidaouia imposed herself next to Cheikh Mwijo, Haim Boutbol and Zohra El Fassia. Jewish artists have magnified the Jewish-Moroccan heritage highlighting the presence of Jewish songs in the Moroccan music scene that are taken up and sung by all Moroccans.

More contemporary artists such as Vanessa Paloma, a Judeo-Spanish singer specializing in the Judeo-Moroccan musical repertoire show us the depth of her musical heritage cradled by the Judeo-Spanish songs of her mother from Tangier.

After the “Reconquista”, exiled in the same way, Jews and Muslims lived together in exile in the countries of the Maghreb where they brought many elements of this brilliant civilization. The misfortune that befell them led both communities to the same song of regret: “asafi cala diyâr al-Andalus” (Great is my regret for our past in the land of Andalusia). Thus, they had participated actively, for centuries, in the same history, and in the same national entity. They found a similar atmosphere in the host countries and quickly assimilated to the Arab-Amazigh culture, which was very similar to their own in many aspects. (15)

Moors and Jews were going to live side by side again, almost merging: the same customs and mores, except for a few details, very similar, if not identical, common memory and cultural heritage that they were equally concerned about preserving from oblivion by having them enter either in the synagogue (16) or the mosque.

On this particular, point Jessica Roda and Stephanie Tara Schwartz write: (17)

‘’Throughout his life, Samy Elmaghribi was dedicated to the preservation, institutionalization, and transmission of heritage of mainly Moroccan liturgy and popular music that he associated with Al-Andalus (Arabo-Andalusian music). For him, his dedication to music was a way to recreate the home he left in Morocco, a home infused with nostalgia of a time and a place he quit at the peak of his career (Silver 2020). His interest in heritage-building was in constant dialogue with his contemporary creations, his fellow generation, and debates of the time. His actions both at the synagogue and on stage show us that, for him, preserving tradition meant focusing on transmission and reinterpretation. He clearly navigated, both during his experience as hazzan and pop singer, between solidifying existing heritage and imprinting his own individual signature. This preoccupation about the safeguarding and respecting of “traditional repertoire or practices” and the necessity to update these practices so that spiritual or musical leaders could adapt them to their times, is nothing new. Anthropologists and ethnomusicologists have shown how oral tradition is constituted by reception, reinterpretation, and transmission (Picard 2001), and is constantly modernized according to the times. In the case of Samy Elmaghribi, his experience—both at the synagogue and on stage—gave Moroccan music of Al-Andalus, both through Jewish liturgy in Hebrew and popular styles in Arabic, a chance to be recognized as art music in the Western and global world.’’

‘’La musique juive du Maroc / Morocco’s Jewish Music” is the title of a book by Moroccan researcher Ahmed Aydoun, who has undertaken to make the world discover the facets of the vast and varied Moroccan culture. (18) Moroccan Jews have always been part of the socio-economic landscape of the Kingdom and have never abandoned their own heritage, which has enriched the Arab and Amazigh Muslim legacy for centuries. For the author, the interest in Jewish music is, therefore,

“an expression of our attachment to our Moroccan identity, the foundation of several cultures and religions.” (19)

In the same vein and according to the Moroccan artist of the Jewish faith, Maxime Karoutchi,

“Jewish music in Morocco is essentially Moroccan music.’’ (20)

He did not fail to pay tribute to Albert Suissa, one of the greatest Moroccan composers of the Jewish faith, who wrote nearly 1000 Moroccan songs.

As an integral part of the Moroccan cultural heritage, Jewish music is worth today, according to Ahmed Aydoun, to be catalogued and disseminated in its original form,

“before it is distorted by the revivals inspired by the era of time.” (21)

Judeo-Maghrebi music is often a popular derivative of the Nûba, and often begins in the same way: in long, poignantly nostalgic vocalizations against a background of very light strings and percussion. Then the whole thing gets carried away in a formidable arabesque ornamented with honeyed voices. Among the voices there are: Mouzino, Sheikh Zouzou, Blond Blond, Samy EAytal Maghribi, Salim Halali, Raoul Jouno among men and Leïla Sfez, Habbiba Msika, Louisa Tounsia, Saliha, and Zohra El Fassia among the women.

Judeo-Andalusian music has not only enriched Moroccan Judaism in its particularity but has also contributed to the development of the substantial values of Moroccan culture. This is visibly present at the heart of Andalusian music in the full extent of its repertoire. (22)

The Maghreb countries belong to the same origins, to the same civilization, and have experienced a similar cultural process. Several variants of their common artistic heritage come from the same source, the one commonly referred to as Arab-Andalusian music. Thus, Malûf is widespread in Tunisia, Attarab al-Gharnati is rooted mainly in Algeria, while the music known as al-Âla is exclusively associated with Morocco.

Indeed, the association of Andalusian music with Morocco emanates from an undeniable historical truth, resulting from its situation in the northwest of the African continent, and its proximity to the Andalusian country. Therefore, Morocco was naturally inclined to see its music closely influenced by the artistic contribution of the mass of Andalusians who had taken refuge in the country.

Over time, the Andalusian culture in its various components had spread through the oral tradition and had taken root particularly in the main historical cities such as Tetouan, Fez, and Salé, while the cities of Rabat and Oujda had adopted a special kind of Andalusian repertoire famous in Algeria, Tlemcen and Algiers, and which is known as Attarab al-Gharnati.

Andalusian and Attarab al-Gharnati music is taught in every cultural complex or school in the main cities of Israel. Jewish artists have not only contributed to popular culture in terms of musical interpretation. Over the centuries they have, also, composed many songs in dârija (Moroccan Arabic dialect).

Andalusian music

Moroccan Andalusian music is thus a synthesis of Arab, Amazigh, and Spanish musical traditions. It is clearly different from oriental music. Andalusian music has seen a great collaboration between Jews and Muslims and Morocco has counted great authors, composers and Jewish performers. (23)

This music is present in all Moroccan homes and in many Algerian and Tunisian homes, also. It is interesting because it offered and still offers a particular ground of collaboration and understanding between Jews and Muslims as much in Morocco as in Algeria or elsewhere in the Maghreb. (24)

The economic and professional coexistence of Moorish and Jewish communities, whose complementarity was vital for the Jewish communities, also multiplied the opportunities for personal and cultural encounters between Jews and Muslims. These encounters resulted in the permanent borrowing of oral and musical traditions by Jewish amateurs and professionals and the mixing of cultural and artistic traditions. (25)

On the nature of the Andalusian music and its identity Dwight Reynolds writes: (26)

“Among the many intellectual and artistic contributions with roots in medieval Islamic Spain , Andalusian music is probably the most widely known in the Arab world and the least well known in the West.1 Andalusian music certainly merits attention in its own right as a rich tradition that has been transmitted orally for more than a thousand years and that continues to be performed in many regions of the Middle East , but it also merits special attention as the primary vehicle for the collective memory of, and nostalgia for, medieval Islamic Spain , which constitutes such powerful aspects of Arab and Sephardic Jewish cultures. Although in modern times we may “remember” al- Andalus through images of monumental architecture, such as the Alhambra and the Great Mosque of Córdoba, these images did not circulate among Middle Eastern Arabs or Jews during the centuries after the expulsions. The writings of even the most famous Andalusian authors, such as Ibn Rushd (Averroes), Ibn ʿArabi , Ibn Hazm , Judah Halevi , Samuel Hanagid , and Maimonides , were only studied by a small intellectual elite. It is rather Andalusian poetry—specifically poetry conveyed in song—that has spoken powerfully to Arab and Sephardic communities over the centuries through performances in diverse contexts such as weddings, festivals, cafés, Sufi lodges, synagogues, wealthy private households, and royal courts. In the daily lived experience of Arabs and Sephardic Jews, songs of al- Andalus (or in the Andalusian style) have remained the single- most potent catalyst for the deep emotional ties felt even now toward a society that dis-appeared half a millennium ago.”

In recent years, Jews of Moroccan origin living in Israel and elsewhere have made contact with Morocco again and this population is gradually rediscovering Andalusian music. The Andalusian Orchestra of Israel (27) has been established in 1994 and offers a new field of collaboration between Jews and Arabs. Moroccan Muslim musicians perform in Israel, and Jewish musicians from Israel and elsewhere perform in Morocco and share generously experiences and artistic creations. (28)

In Morocco, people are rediscovering the great authors, composers and performers of North African Jews such as Samy el Maghribi (1922-2008), Salim Halali (1920 – 2005) and many others, and this country is paying tribute to them and making them its national heritage of which it is very proud.

In 2007, Maurice El Medioni was at the heart of the rendezvous of Jewish-Arab music at the 4th Festival of Essaouira with the Israeli Rabbi Haim Louk. In 2008, the 5th Andalusian Festival of Essaouira was dedicated to the work of Samy el Maghribi, whose real name is Salomon Amzallag, known, also, as “The Lion of Morocco”. His daughter Yolande Amzallag performed there with Maxime Karoutchi, who is often seen on television sets and stages in Morocco with local Andalusian orchestras.

Posthumously Samy el Maghribi was decorated with the wissâm of national merit of the order of commander, which was awarded to him by HM King Mohammed VI on the occasion of his 80th birthday. Moroccan television, also, devoted a special program to him and another one was broadcasted at the time of his death. His funeral was attended by Ambassador Mohamed Tangi who read verses from the Koran, and an Algerian director who was preparing a film about Samy.

In 2005, Essaouira paid tribute to another great Judeo-Moroccan-Algerian musician Salim Halali (1920- 2005) born in Annaba (Bône) in the Jewish family of Boulanger. At the age of 14 he left Algeria for Paris. In 1938 he met Mahiedine Bachertazi and later he sympathized with the singer, humorist, author and composer Mohamed El Kamal. Following this meeting and their collaboration, appeared the first records of Salim, with tunes such as “Mounira ya Mounira“, “Nadera” and “Andra“. ‘’Nadera” and “Andaloussia” became the biggest successes before the Second World War in North Africa.

During the Nazi occupation, Salim Halali will be saved, on royal instruction, by the Moroccan Kadour Benghbrit, first Rector and founder of the mosque of Paris who will make him pass for a Muslim, by inscribing the name of his father on a tomb in the Muslim cemetery of Bobigny. Some of his relatives, alas, were murdered in the Nazi extermination camps. (29)

After the war he created in Paris the oriental cabarets “Ismailia follies” and “Sérail”. The great Arab Diva Oum Keltoum admitted to having a weakness for his particular voice. In 1949 he left France, to settle in Casablanca where he created the oriental cabaret “Le Coq d’or”.

Liturgical Jewish music

The Sabbath (Shavat in Hebrew), a day of rest, is an institution, of great importance, in Jewish life. And the songs that punctuate this particular day have a large place in it, both in the synagogue with the five services of Kabbalat shabbat to Motsei shabbat, and at home with the rituals of lighting the candles, the Kiddush (blessing of the wine) on Friday evening, the Birkat hamazone (thanksgiving at the end of the meal), or the Havdalah (the last Kiddush at the end of the Shabbat). It is also customary to sing, during the four Shabbat meals, numerous religious poems called Zemirot (or Tish nigunim among the Hasidim). Shabbat thus allows one to find one’s inner way through one’s outer voice.

At Moroccan homes, the Sabbath begins Friday evening some 20 minutes before sunset, with the lighting of the Sabbath candles by the wife or, in her absence, by the husband. In the synagogue the Sabbath is ushered in at sunset with the recital of selected psalms and the Lekha Dodi, a 16th-century Kabbalistic (mystical) poem. The refrain of the latter is “Come, my beloved, to meet the bride,” the “bride” being the Sabbath. After the evening service, each Jewish household begins the first of three festive Sabbath meals by reciting the Kiddush (“sanctification” of the Sabbath) over a cup of wine.

On this topic, Rachid Aous points out that: (30)

‘’In Judeo-Arab song and music, there is a type of song with a strictly Hebrew melodic style which is expressed in cantillation specific to the aesthetics of synagogal song prevalent in the Sephardic Maghrebi cultural area. This melodic aesthetic is found essentially in the interpretation of the Baqqashots (songs of supplications) and the Piyyutims, an aesthetic conveyed solely by the oral tradition, that is to say without musical notation.

For the rest, the tradition of Judeo-Arabic singing, which has been the subject of audio recordings, has long been carried by great singers such as Haïm Louk, Rabbi David Bouzaglo and Amzallag in particular. They sang in Hebrew or in Arabic texts from the Judaic sacred repertoire to melodies specific to North African-Andalusian music, melodies relating both to so-called Arab-Andalusian classical song (Âla, San’a, Gharnâti, Malûf…) and melodies related to popular songs. Thus the examples below taken from traditional liturgical chants interpreted by Haïm Louk, as by other North African Jewish singers, to tunes from the Moroccan Ala and an Algerian Naqlab Muwwal, in this case, to the characteristic melody of the famous song Qoum Tara (stand up and admire), poem and melody derived from the Algerian San’a.’’

Like the Psalms, the Baqqashots (31) are part of the hymn and the elegy. The Spanish poets and those of the Kabbalist School of Safed cultivated this poetic and musical genre, which is found in the Maghrebi Jewish liturgy of the dawn as well as during sabbatical vigils known as Baqqashot vigils.

The Andalusian music practiced by Moroccans of Jewish faith, descendants of the Judeo-Andalusians of Moorish Spain, is called piyyûtim (32) and trîq. This style originated mainly in Meknes and Tafilalet. Later, Judeo-Moroccan Andalusian music was exported to countries where the Judeo-Moroccan diaspora settled (Israel, France, Canada, United States, etc.). Before their massive departure from Morocco, Judeo-Moroccan artists were also represented in different musical styles such as cAïta, Shacbî, Gnawî, and Melhûn. (33)

The piyyutims of Moroccan Jews generally make a free and varied choice of Andalusian melodies, so as to obtain a well-ordered sequence obeying the principle of progressive acceleration borrowed by Sephardic rabbis who composed texts explaining each verse of the Torah. (34) They are sung in religious ceremonies just like the psalms of David. Andalusian, too, and sometimes using the same melodies, are the Samâc or Arabic songs in honor of the Prophet Muhammad.

Jewish poets writing in Hebrew often took their models from Arabic poetry, (35) whose way of thinking they adopted; thus a Jewish song was very close to an Arabic song and Muslim thought. Both communities listened with equal enthusiasm to the Nûbas they had taken with them from their first homeland, Andalusia. They, also, appreciated the works of their new culture in dialectal Arabic, a language commonly spoken in both communities that produced the rich and varied Melhûn.

On the origin of Judeo-Arab Andalusian music, Joseph Chetrit writes: (36)

‘’Numerous Arab chronicles mention, as early as the ninth century, the cooperation of Jewish and Muslim musicians in Andalusia, especially in Cordoba. There it was the Jewish musician Mansur who was commissioned to accompany, in 822, the great Ziryab, who had fled Baghdad and was to create at the court of Abd ar-Rahman II a new and vast body of music, since called “Andalusian music”. This vast corpus was initially made up of 24 mega-symphonies, called nawba (pl. nawbat) and each articulated around 4 different rhythmic modes, from the slowest to the fastest, called mizan (pl. mayazin). It was performed, enriched and transformed, from the 9th to the 13th century, in the princely courts of Andalusia and the Maghreb, and gave rise to different traditions that have been perpetuated to this day in the different countries of the Maghreb. From the beginning, as this vast musical corpus was studied orally and transmitted from master to disciples, it was lyrical and romantic texts, and often even bachic, written in the popular or semi-classical genres of the jazal, muwashshah and tawshih, that ensured its preservation and transmission.’’

Jewish religious cantor: Haim Louk

Rabbi Haim Louk was born in Casablanca, Morocco in 1942. He became famous very quickly and at a very young age was considered a prodigy of Jewish liturgical music. Endowed with an exceptional voice and a remarkable talent, he was encouraged and followed by different masters and more particularly by the great master of the Moroccan Jewish liturgy, Rabbi David Bouzaglou ‘Zal, and the Muslim Abdessadeq Cheqara, the Andalusian voice of Tetouan. Based on his extensive knowledge of the Sephardic tradition, he symbolizes this dual Jewish and Arab identity.

His faith and rabbinical knowledge were as important as his passion for Sephardic liturgy and his love for religious poetry. Haim Louk combined the classical tradition of Moroccan Andalusian music with the Hebrew repertoire of piyyutim and baqqashot

During his studies in different Yeshivot in England, Morocco, and Israel, he never stopped working and progressing in his art. And during his various functions as a teacher or director in different schools in Morocco, and Israel, he perpetuated the tradition of Jewish liturgical music to the benefit of his students.

After living in Morocco until 1964 he decided to move to Israel, where he lived until 1987. That same year, Rabbi Haim Louk moved to Los Angeles to take up the position of Rabbi of the Sephardic community Em Habanim.

Since his return to Israel and in the tradition of Sephardic masters and scholars, he has combined his studies of rabbinic texts with his work as an educator to combine his musical talent for Sephardic liturgy with his love of religious poetry.

Internationally recognized as a virtuoso of classical Andalusian music, he has produced and broadcast numerous audio and video recordings, which can be heard, and seen on various media. He has given numerous recitals and received rave reviews in Morocco, Israel, Spain, France, Belgium, Canada, Poland, and the United States.

On the Moroccan synagogue service music and singing, Edwin Seroussi writes: (37)

‘’The Moroccan Jewish worship, namely daily, weekly and holiday prayers, has been hardly analyzed contextually. Unlike the prestigious paraliturgical piyyut, liturgical repertoires mark sonic difference between Jews and Muslims in Morocco. They comprise an intimate space of Jewish sound that links the Moroccan Jewry not so much to its immediate Muslim neighbors but rather to the diasporic Jewish commonwealth of Sephardic and Oriental pedigree and, to a certain measure, to modern colonial contexts, mostly French-Jewish. Yet, this intimate musical space of the Moroccan Jews still bears some traces of the non-Jewish surrounding. It is not deprived of “musical Andalucianisms” at different levels, some at the level of voice production only, others much deeper that comprise, in my opinion, a modern development.

There are of course aesthetic reasons too for the lack of emphasis on the liturgical repertoires of the Moroccan Jews among the contemporary agents of musical production and music scholars. This music is highly functional; it is generated by the structures and contents of sacred texts whose ceremonial performance and clear-cut pronunciation precedes musical concerns. These texts are an assortment of very diverse sources and registers: biblical and oral law passages, post-biblical prayers in poetic prose and poems (piyyutim) spanning almost a millennium of literary history. This textual mixture creates a sonic tapestry that moves between fast non-metered mumbling on a single recitation tone to clear-cut florid melodies with fixed meter with various permutations of melodic and rhythmic formations in-between these two extremes.’’

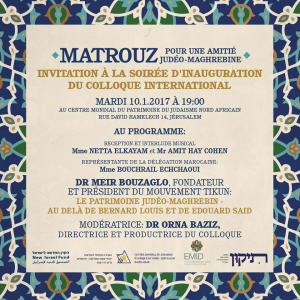

The Matrûz

The Matrûz – in Arabic, what is embroidered – is an oral tradition. It is an old musical tradition of the Judeo-Arabic cultural heritage attached to the Hebraic, Muslim, and Christian artistic practice current in the melting pot of multicultural Andalusia. The Matrûz designates a musical concept of Judeo-Arabic crossbreeding characterized by the alternation of Arabic and Hebrew in the lyrics. It is a music of oral tradition still present in certain Moroccan circles that value this common heritage of Jewish, Muslim, and Christian cultures of Andalusia. Usually, the first part of the poetry of the songs of the art of Matrûz is composed in Arabic, while the second part is organized in Hebrew, and the orchestras interpret them on the same rhythms and melodies from the Gharnati repertoire. (38)

The Matrûz, which originated in the Middle Ages in Andalusia, in Spain that was Muslim at the time, is a song often practiced by Andalusians of the Jewish faith, mixing Hebrew with Arabic in an exceptional harmony. The Matrûz is the result of Arabic, Berber, and Muslim influences. Due to the waves of immigration of Muslims and Jews fleeing the Christians of Spain, this Arab-Andalusian music is more present in Morocco than in any other country. It symbolizes the life of the Jewish ancestors who lived in perfect conviviality with their Moroccan Muslim brothers.

Rachid Aous introduces the Matrûz in the following terms: (39)

“The Matrûz philosophy is marked by the values of convivial tolerance shaped in Andalusia, within the framework of the Civilization of the Arab-Muslim West, which opens with the occupation of Spain at the end of the VIII century and closes with the fall of Granada in 1492. It is a privileged period of history marked by understanding and a fruitful cultural and scientific dialogue between Jews, Christians and Muslims, united by a common musical language: the modal system. All this language, a true bridge between the two shores of the Mediterranean, is found in Simon Elbaz’s “Matrouz”.

The Judeo-Arabic tradition born in the land of Islam, where the Arabic language is practiced, only survives outside these territories. It is only found in Israel, and particularly in France. Carried by Sephardic Jewish artists of Maghrebian Arabic-speaking culture, it finds its fullness thanks to the freedom of expression that characterizes the democratic countries that are now the receptacle, where many Jews of this origin live. And this is not without fruitful consequences for the Jewish-Arab dialogue.’’

Simon Elbaz is considered the renovator of the Matrûz, he was inspired, at first, by this art based mainly on the alternation of two languages, Arabic and Hebrew. He enriched this tradition by relying on a compositional process based essentially on the interweaving of languages: Hebrew and Arabic in particular, but also French, Latin, Judeo-Spanish, and also music of different traditions: Judeo-Arabic, Maghreb-Andalusian, Oriental, medieval, and Berber, and, finally, different modes of expression: music, song, storytelling, and theater, which, for the first time, “entered the scene” in the Matrûz repertoire with Elbaz performance.

Simon Elbaz was inspired, at first, by this art based mainly on the alternation of two languages, Arabic and Hebrew. He could have kept and looked at this heritage as an object of nostalgia; he, instead, took possession of this artistic tradition and renewed it all together, by associating the sacred and the profane and by relying on another compositional process based on the interweaving. (40)

Simon Elbaz, from a triple Franco-Jewish-Maghrebi culture, of Moroccan origin and born in Boujaad, devoted a large part of his life to Matrûz. He is an author, actor, composer, and singer. Drawing his inspiration from the poetic and musical tradition of Andalusia, he has created a new kind of show, linked to tradition, but resolutely turned towards the future and modernity.

Matrûz is an invitation to a journey into the sounds of intertwined languages and music: the repertoire of this genre of music is made up of original songs related to the Hebrew, Muslim, and Christian cultural traditions of Andalusia, as well as songs from different traditions, especially Judeo-Moroccan. The compositions and arrangements are based on the successful and rewarding interweaving of languages: Hebrew and Arabic in particular, with French, Judeo-Spanish, Berber, Latin, and music genres: Judeo-Arabic, Oriental, Maghreb-Andalusian, medieval, and Judeo-Spanish. A cappella or accompanied by instruments, the songs are introduced in French by short poetic sequences or punctuated by vocal and instrumental improvisations, giving a glimpse of various aspects of the Judeo-Arabic culture in its singularity.

The Noche de Berberisca (Berber night)

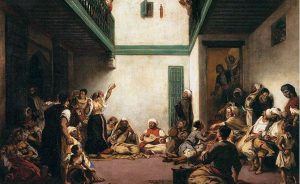

Among the traditional ceremonies of the Moroccan Jews, the richest, most original, and most picturesque is undoubtedly the one called the henna or henna party or noche de novia, noche de Berberisca or Noche de paños in the communities of the ex-Spanish zone (Larache, Tetouan, Ksar El Kebir, Azilah, etc.) and in Tangier which was a city in the international zone.

This celebration takes place during the week before the wedding, in an atmosphere of rejoicing, songs for the bride, music of youyous, sumptuous dishes, cakes and pastries with honey and almonds, and exhibition of the trousseau, the Shabbat that precedes the wedding called: Shabbat a kala.

The most awaited moment is the one when the bride-to-be makes her appearance, at the head of the procession, adorned with her most beautiful finery, carefully made up, eyes enhanced with kohl, cheeks revived with carmine, dressed in the superb red, green or wine-colored velvet dress, gleaming with golden embroidery, pearls, and sparkling stones. This ceremonial costume is called al-keswa l-kbîra (in darija the ‘’big dress’’) or, among the Jews of the former Spanish zone, traje (or vestido) of berberisca, or ropas de oro, or traje de paños, among the Jews of Tetouan.

The Noche de Berberisca (Berber night) or Noche de paños (night of the cloths) or Lilt al-henna (night of the Henna) is a ritual celebration of fertility and holiness. (41) It is a typical custom of the Jews of northern Morocco that they brought with them from the Iberian Peninsula on their expulsion in 1492.

Traditional Sephardic songs, youyous and hearty meals punctuate this picturesque celebration organized on the eve of the wedding, usually on Tuesday, because it is the day of the creation of the moon and the sun and the unification of man and woman in the Hebrew Genesis.

The families of the bride and groom gather to celebrate the holiness and fertility of the bride, as a living symbol of etz haim, the tree of life, from the Torah. The oldest and most distinguished people sing their blessings and praises to the bride, during a procession similar to that of the Sefer on Simhat Torah, and then enthrone her on the talamon, dressed in the sumptuous traje de berberisca. (42)

After the purification bath (tebila) and a special liturgy, led by a song, where the piyyutim “sung poems”, prevail over the ordinary ritual. The groom dresses in his ceremonial apparel, an indigenous costume including a pair of pants made of cloth (serwal), an embroidered vest with silk buttons (bediya), a long cloth jacket (zokha) tightened at the waist by a silk belt.

The bride is enthroned on the talamon (from the Spanish talamo, ‘’chair’’), made up, perfumed, adorned with gold and precious stones, resplendent in her ceremonial costume, the large and sumptuous outfit called al-keswa l-kbira whose pieces are the following: wimple of velvet embroidered with gold (ktef), bodice of garnet or green velvet, enhanced with gold braids and silver buttons (ghonbaj); skirt of velvet of the same color (zeltita), loaded with gold braids and under which are hidden many petticoats (sayât); wide and stiff belt of velvet embroidered with gold and pearls (hzâm or mdamna); babouches embroidered with gold (sherbîl); wide sleeves of embroidered silk veil (khmâr and tesmira); crown headdress loaded with pearls, emeralds, rubies, gold coins etc. (khmâr or swalef); long scarf in beautiful silk which fixes the hair (festûl); white or green silk scarf (sebniyya) which is covered with a light white veil (elbelo from the Spanish velo) lowered on the face.

On the Judeo-Moroccan music of northern Morocco, Paloma Vincent El Baz writes: (43)

‘’One of the points that are most significant about the transmission of identity through the music of the Jews from northern Morocco is that it is performed through elements that derived from cultures of contact, through an oscillation between its musical repertoire which is perceived to be exclusively internal and the repertoire of the ‘external’ world. As previous studies of Maghrebi music have shown, music genre, social position and expressive behaviour are a common principle in the Maghreb and have social and political meaning in relation to one another (Langlois 2009, 227). One can thus conclude that public sphere repertoires, which I name below as ‘external’ are crucial in informing and influencing social and political meanings around Jews within the nation and ‘internal’ repertoires serve to reiterate cultural specificity and cement the minority group.’’

The borrowings of the Jews of the Maghreb from the Andalusian music and the qasîdah?

The musical styles of the Muslim, and Jewish communities appear to be very colorful and mutually influential, proving the harmony of their cohabitation and social cohesion. The Judeo-Maghrebi singers have been the actors-witnesses of music shared for centuries with their Muslim “compatriots”, cultivating together the flowers of the rhetoric which draw their essence and their fragrance from the blessed times of Andalusia, that was undoubtedly the crossroads of a Mediterranean cultural bubbling where Jews, Christians, and Muslims respected each other and fraternized warmly.

Among the beautiful voices of the Maghreb, let us remember: among the men: Mouzino, Sheikh Zouzou, Blond Blond, Samy el Maghribi, Salim Halali, Raoul Jouno, and Sheikh Mwijo among the men and among the female voices Zohra El Fassia, Leïla Sfez, Habbiba Msika, Saliha, … The Moroccan-Andalusian music has gone beyond the borders of Morocco and the Maghreb to other horizons, thanks in particular to the mobility of the Moroccan Jewish immigrant community and its fierce attachment to its culture despite all the apparent effects of the constraints of immigration, with, in particular, the creation of the Andalusian Orchestra of Israel founded by Avi Eilam Amzalag. (44)

Very often in the orchestras are found side by side Muslim and Jewish musicians and singers. Only the words of the songs make it possible to differentiate the origins of the distinct musical structures. The so-called Judeo-Arabic music is a popular derivative of the Andalusian Nûba and offers the same similarities to the listener. They prelude in the same way: long vocalizations which express the feeling of nostalgia on an instrumental bottom with plucked or rubbed strings and percussions. Then, the miracle! The whole thing blows up into a formidable instrumental suite composing ornamental arabesques to the velvet voices of these singers.

The Maghrebi Jews who have excelled and innovated in this field are distinguished by their assiduity, their spirit of perseverance, and their deep investigation. They safeguarded, restored, and enriched this art and propagated it beyond its area. Rabbi David Bou Zaglou, Rabbi David Ben Barukh known as David Iflah, David Kaïm El Fassi, Josèph Banon, Melloul, Haroun El Mesfioui, are considered as the pioneers in Andalusian art.

The Gharnati music which constitutes besides the Andalusian music one of the pillars of the classical musical heritage of Morocco, knew great participation of the Jews who enriched it. One finds at their head Youssef Eni Bel Kherraia, Mrs Marie Soussan, Lebradi known as Sassi, Fifiné, Edmond Yafil known as Chbab, and Reinette l’Oranaise.

Judeo-Arab Andalusian music has not only enriched Moroccan Judaism in its particularity but has also contributed to the development of the substantial values of Moroccan culture of communion and tolerance. This is visibly present at the heart of Arab-Andalusian music in the full extent of its repertoire. For this reason, the Essaouira Atlantic Andalusia Festival was created to celebrate Judeo-Arab shared culture in Morocco.

The Golden Age

Haim Botbol, Albert Souissa, Samy el Maghribi…, names that few Moroccans recognize today. Yet these Moroccan Jews were real stars in their time. Like their Muslim compatriots, Jews have long been great admirers of Shacbî music. And one could not imagine a wedding or a bar mitzvah without the presence of a popular music group. It is quite natural that many Jewish singers have long distinguished themselves in this field. Maurice Elbaz, an artistic producer explains: (46)

“The Judeo-Moroccan chaabi music has flourished since very early on, in the sense that in relation to the Jewish tradition, there were no prohibitions. There were fewer taboos than among their Muslim compatriots and they were helped by a certain tradition of synagogal singing.”

Passed on from mcalem to mcalem, Moroccan Shacbî music remained relatively elitist until the Protectorate. With the arrival of the recording media, this popular music was democratized and reached all social strata of the kingdom. Jewish artists, very much influenced by their Algerian co-religionists, took the initiative very early on and new stars saw their fame grow throughout the four corners of Morocco.

This is the case of Zohra El Fassiya, diva of the Shacbi song of the 40s. Born in 1905 in Sefrou, she began her career by singing Melhûn in the 20s of the last century. She specialized, little by little, in a more festive Shacbî music, marked by percussions and called the Hawzî. Already popular in the 30s, Zohra El Fassiya managed to propel her career through the radio. Her fame went beyond the borders and she became a real star in Algeria. Among her most popular songs and which will be taken again years later by many singers of Shacbî, are: lghorba u lfraq, ya warda, or the unforgettable hbibi diali fayn howa.

Samy El Maghribi, another figure of the Judeo-Moroccan song, has also marked the history of Shacbî. Born in 1922 in Safi, he left with his family to Rabat and joined, at the age of 7, a group of the mellah of the capital. Passionate about Andalusian music, he learned to play the cûd (lute) on his own before joining the Casablanca Conservatory of Music. It is this last experience that allows him to frequent the greatest masters of the Andalusian song. At the age of 20, he left his job as a sales manager to devote himself exclusively to music. Samy El Maghribi, whose real name is Salomon Amzallag, is a true master of Moroccan classical music.

On his account, Maurice El Baz says: (47)

“The style of Sami El Maghribi is atypical. He is one of the pioneers of the Moroccan classical song. His songs are all characterized by an intro, a verse, a chorus and a longer rhythm, while his lyrics were researched and more romantic.”

During the 50s, this singer celebrated his love for his country and in 1955, greeted the return from exile of King Mohammed V with: Alf hniya wa hniya, goulou 3-slama l-sidna Mohammed al-khamiss soltan almaghrib. In 1960, following the earthquake in Agadir, he paid tribute to the victims with his Qasîdat Agadir.

But to speak of Shacbî song without quoting Albert Souissa is to deny the history of the origins of the modernization of this musical genre. Some call him “King of Bendir“, others see him as the one who “created 90% of the chaâbi melodies we know today“, says El Baz. Because, being neither in the Andalusian spirit, nor in that of the Melhûn, Souissa set out to create his own music, whose words were all in darija, sung on the rhythms of the inevitable bendir (tambourine).

Israel, the new Eldorado of Moroccan Jewish singers

By the 1960s, the majority of Moroccan Jews had already left the kingdom. A tragedy for the Jewish-Moroccan song.

“The real problem was that when the musicians left, they took their orchestras, their recordings and their instruments with them,”

says Maurice El Baz. Having left Morocco, most settled in Israel and Canada and continued their careers in their new host countries. In Morocco, the Jewish Shacbî song is all the more penalized that in the 70s, political repression is also accompanied by a control of artistic productions.

Patriotic songs abounded on radio and television, while Shacbî music, both Muslim and Jewish, was marginalized by the authorities. It is only during the 80s that new figures emerged again, like a certain Pinhas.

“It is thanks to marriages and especially to the arrival of Middle Easterners, especially from the Gulf, that singers are able to revive their art,”

explains El Baz for whom

“Saudis could give up to 50,000 dirhams to a singer per performance.”

Nowadays, most of the Jewish Shacbî singers perform in Israel, if they cannot do so in their country of origin. No less than seven Jewish Andalusian music orchestras perform regularly in Israel. In Morocco, the Jewish Shacbî cannot sell itself. The structures for a real take-off of this art are absent. An observer of the Moroccan artistic scene does not hesitate to confide that,

“fortunately, there are still producers adventurous enough to dare to lose money by organizing a concert, like that of Botbol.’’

Some prominent Moroccan Jewish singers

Pinhas Cohen: Icon of Moroccan Jewish music

He is a legend of the Moroccan popular scene. Pinhas Cohen was born in Casablanca in the famous district of Verdun. Originally from Fez, he has immersed in music thanks to his father Azar who was a sofa maker, but who was also a talented lute player who used to animate family parties (weddings, Henna…). Pinhas studied engineering, but the love of music led him to the art world, becoming, in just a few years, one of the most important and recognized Moroccan artistic phenomena.

This Shacbî singer revolutionized the artistic landscape in the 1980s, and 1990s, and he is recognized as the star of wedding parties in Morocco and even abroad. He often sang about love, and romance, which made him more adorable, especially to the female public. He stands out thanks to his festive style and his natural elegance.

His specialty is the popular song and the Shgûrî, a musical genre characterized by its fast rhythm, its dancing music, and its audacious lyrics that sing of love, uprooting, and nostalgia of the beautiful Andalusian era, before the expulsion of Jews and Muslims.

Haïm Botbol: Monument of the music

At 75 years old, he has accumulated more than 60 years of stage experience. Inheriting the first name of his uncle, a dressmaker at the Palace until 1961, Botbol the musician, in the lineage of Samy El Maghribi, is the custodian of the Judeo-Moroccan musical heritage. From the Sijlmassa in Casablanca to the mythical cabarets of Tangier, he has accompanied the country’s upheavals from the 1960s to the present day. Nostalgic for the Hassan II era, the living legend was also one of the artists appreciated by the king, who extended by one hour, in 1968, one of his concerts, broadcast live on TV. A true monument of Moroccan music (his repertoire includes some 300 songs), he recorded with Abdelhadi Belkhayat and Hajja Hamdaouiya.

Zohra El Fassiya: the pioneer of melhûn

Known by her pseudonym Zohra El Fassiya (born in 1905 in Sefrou near Fez – died in 1994 in Ashkelon), she was one of the emblematic figures and pioneers of Melhûn, an authentic Moroccan musical genre. She began her artistic career singing Moroccan Melhûn in the 1920s. In the 60s she lived in Casablanca, precisely on Sarah Bernard street, where many witnesses could hear Zohra El Fassia’s voice in the whole neighborhood. After her great success, she left her native country of Morocco to settle in Ashkelon until her death in 1994.

Emile Zircon

Sephardic and Moroccan, he immigrated to Israel. Emile Zrihan became known to a large public as a star singer in the Andalusian orchestra of Israel. Although he is not well known in France, he has all the qualities needed to seduce the lover of oriental variety music. He is a connoisseur of Arab-Andalusian music and the art of mawwâl (with his splendid Ma Yafou Dadaich), which was his school as it was for many Jewish artists, and was a vector of tolerance for him.

Just as it was the case for Tonton Raymond (the future Enrico Macias who played in his orchestra) with the Malûf in French Algeria, Zrihan with his beautiful voice is committed through music to bringing people together and to the pacification of the latter.

Maxime Karoutchi: The crooner of Casablanca

Of the sentinels of the Moroccan Jewish musical heritage, Maxime Karoutchi is among the youngest… and the last. Settled in Casablanca and originally from Essaouira, the man who was destined for a very wise career as an engineer finally opted for the keyboard, then for singing, to the great astonishment and pride of his father. He did his scales in the family orchestra, before taking his momentum and being, today, the most known Moroccan Jewish singer. From weddings to palace parties and vibrant tributes (like the one dedicated to Botbol), Maxime Karoutchi, cousin of Roger Karoutchi, vice-president of the UMP (right-wing party) in France, is today the representative of the country’s Jewish and Arab-Andalusian music.

Sheik Mouizo/Mwijo

Moussa Attias, known as Sheikh Mouizo/Mwijo, is one of the greatest masters of Moroccan Jewish songs. Born in Meknes in 1937, he began singing at the age of 25. Mouizo descends from a line of singers and composers, going back to his grandfather. His father Yaakov Attias was a percussionist who played in the Mâalem Ben Haroush ensemble. The latter moved to Israel and Mouizo accompanied him in his last days. To thank him for his presence, Ben Haroush gave him his songbooks, which would be the source of his rich repertoire of more than 500 traditional songs from the Maghreb, as well as other written songs, including “Tanjiya“, “Ma Kayan Kheir“, “Ibrahim Al-Khalil“, “A ibad Allah“, “A labnat” and “Ghazali houa Sbabi“… His songs with very contextual lyrics have crossed generations of Moroccan Jewry. Sheikh Mouizo died on May 2, 2020 after a long and inspiring career.

Simon Elbaz: star of Matrûz

Born in Morocco, in Boujaad. He settled in France where he completed his studies in Humanities at the University of Paris IV. For more than twenty years he has devoted himself to the art of Matrûz art, a musical creation based on oral traditions leading to the crossing of cultures and languages: Hebrew, Arabic, French, Latin and Judeo-Spanish. Nourished since his childhood in Morocco by the traditional teaching of Hebrew cantilation and Berber-Arabic-Muslim culture, he practiced singing in Paris with Tamia, Giovanna Marini, Sigmund Molik and the cûd with Hussein el-Masry. He continued his theatrical training with Jacques Lecoq, Jerzy Grotowski and with Peter Brook and Eugenio Barba during working meetings. He interprets most of his musical and theatrical works: Offering, The Song of Songs, Bled-on-stage, Medina-Folies, Mchouga-Mabul, etc.

Coming from a triple French-Jewish-Moroccan culture, he has dedicated himself for more than thirty years to the renewal of Matrûz: ‘’Artistic Creation of Languages, Music and Intercrossed Theater. ‘’ In parallel to his university studies in Human Sciences, he pursued his artistic training as an actor, musician, and singer. He is a member of the El Mawsili Ensemble of Arab-Andalusian music and has performed in plays by authors such as Liliane Atlan, Tahar Ben-Jelloun, Edmond Amran El Maleh, Amadou Hampâté Bâ, Henri Meschonnic, Juan Rulfo, Kateb Yacine, as well as in his own creations, and in films, notably “Where are you going Moshe? ” by Hassan Benjelloun, in which he plays the main role.

He performs in France, and abroad in many festivals, including Avignon, Bourges, Casablanca, Edinburgh, Fez, and Montreal.

Neta Elkayam

Two months after the release of her album composed of covers of three traditional songs from the Jewish-Moroccan heritage, the Israeli artist of Moroccan origin returns with a new album “Arénas” where she explores again her roots by dusting off old songs of the Jewish women of the Atlas Mountains, having transited through the French camp of the Grand Arénas of Marseille.

The artist, who fully assumes her dual Jewish and Moroccan identity and who was discovered in Kamal Hachkar’s latest documentary “In your eyes, I see my country”, has succeeded for years in conquering an international audience by lending her voice to the music of North Africa. A regular at the Festival des Andalousies Atlantiques in Essaouira, Neta Elkayam has been performing on the most prestigious stages in Jerusalem and Casablanca, surrounded by various orchestras and musicians of the highest caliber. She has received numerous awards, including the ACUM award and the Sami Michael award. Also, she was nominated for the Ophir Oscars for her leading role in the musical ”Red Fields” (Mami), 2019.

Jewish influences in the history of Moroccan music

The cultural eclecticism of Morocco translates into a multiplicity of musical influences at the origin of musical genres that today occupy a place of their own in the rich Moroccan musical culture.

Moroccan Jews have left their mark on Moroccan culture in many areas, including music, cuisine, and certain trades. In Israel, Moroccan Jews form the largest Arab community do still maintain close ties with their homeland. Morocco also has many synagogues, sacred Jewish graves, and Jewish courts. In many Moroccan cities, Moroccan Jews lived together in the “Mellah“, the Jewish quarter. They were autonomous and practiced their religion freely. (49)

Judeo-Moroccan music is very strongly influenced by the heritage left by the Moors. This style of music was born in Morocco after the expulsion of Muslims and Jews from southern Spain. Judaism is inextricably linked to the Moroccan soul. A part of Morocco is Jewish and Judaism has its own place in this country and in the heart of its people.

Before their massive departure from Morocco, Judeo-Moroccan artists were also represented in different musical styles in the country: cayta (such as the Judeo-Moroccans of Safi), Shacbî, Gnawî (such as the Judeo-Moroccans of Essaouira), Melhûn. This style little known to the Moroccan public is from a mixture of the Sanca (صنعة) which is a form of music Arab-Andalusian Gharnâtî which mixed with music Shacbî gave birth in the 1920s to this style of music in Casablanca, then it spread to Salé, Rabat, Safi, and Fez, and it even crossed the borders. The great masters of this music are Houssine Toulali, Samy EL Maghrebi, Zohra EL Fassia, nowadays we find EL Merrakechi, the Penhas brothers, Sheik Mouizo and some singers in exile as: Charly, Fabien Rachid Otfi, Nino EL Maghrebi.

This music borrows its modes from Andalusian music, by simplifying them, the text is generally resulting from a Qasîdah written by great masters. This music remains reserved nowadays for the elite, more in private parties. During the song; dancers generally women perform choreography with a white scarf, in their hands, a symbol of the bourgeoisie.

Contrary to the idea received in Morocco that this music is reserved for the Jews of Morocco, according to Moroccan historians, this music was not born in 1920, but quite simply brought by the Muslims driven out of Andalusia, and there is not a piece of Jewish Andalusian music and a Muslim Andalusian music but quite simply a classical Arab-Andalusian music.

Moroccan Jewish singers

Besides urban Moroccan Jewish singing, there is a less-known Judeo-Berber singing and dancing in mountain areas that was quite popular among the Amazigh population of Morocco, Mohamed El Medlaoui introduces this particular art, in the following terms: (50)

‘’The participants in this aḥwash – most likely toshavim – come from the Iglua and Tidili in the central High Atlas. Their aḥwash is characterized by a fairly strong adherence to the canons of the aḥwash of the places of origin. This can be seen, among other things, from the following features: beginning with a functional, but also ritual, heating of authentic tambourines (tagnza) on a brazier (figure im7) in order to adjust their three percussive tones (lhmz “low”, agllaya “medium” and nqqr “high”) ; an improvised ashtray in nnaqus “bell sound”; a good command of the 5/8 quinary rhythm, typical of the aḥwash, with these three tambourine percussion tones (lhmz, agllay, and nnqqr) ; accurate youyous and sober dancing with shoulders and vertical body movement; mastery of the pentatonic modes of the tune repertoire; memorization of a rich repertoire of ancient songs and melodies; accurate chleuhe diction and standard chleuhe pronunciation (no disturbance of sibilants as in the megorashim). On the other hand, men sometimes have difficulty holding the high register, which characterizes the vocalization of Chleuh singing; they sometimes degrade their voice by an octave for certain tunes compared to women.’’

Conclusion: What remains of this Judeo-Arabic culture?

What remains of this Judeo-Arab-Amazigh culture, today that the Jews of the Maghreb are dispersed throughout the world?

In France, the Sephardic community lives alongside the Muslim emigration. In Israel, Maghrebi Jews and Oriental Jews, although in the majority, are treated as marginal minorities.

“This culture has left its mark on the soul of Maghrebi Jews. It still resonates in the hearts, in the uprooted souls of the emigrants in Israel, it resounds in their music, in their songs, in their folklore and their rites. There is homesickness,”

says Haïm Zafrani, a Moroccan Jewish writer who lived in Israel.

In Morocco, none of the representatives of this Judeo-Arab-Amazigh music have been forgotten, neither the masters already mentioned, nor Samy el Maghribi, nor especially Salim Halali, the singer of modernism in the traditional music of the three Maghreb countries. New names have appeared such as Boutbol or Pinhas. As well as new experiences arose, notably those initiated by Francoise Atlan, a soprano who specializes in Sephardic songs and Arab-Andalusian music.

Patiently, since 2007, Vanessa Paloma Elbaz, a researcher, and performer of songs from the Jewish-Moroccan heritage has collected hundreds of recordings and continues to do so in her small office in Casablanca, the economic capital and megacity where the majority of Morocco’s Jewish community now lives. At the end of January 2015, the initiative was presented at the Museum of Moroccan Judaism as part of a screening debate. (51)

With her initiative, the forty-year-old woman said she wanted to revive the memory of the not-so-distant past: in the 1950s, the kingdom had 250,000 citizens of the Jewish faith. But successive Arab-Israeli conflicts made them emigrate to Israel, and numerous departures to France and Canada took place and have, subsequently, reduced this presence to less than 3,000. However, Moroccan Jews remain the main Jewish community in North Africa.

The name of the project – “Khoya: The Sound Archives of Jewish Morocco” – was chosen to reflect this common heritage of Moroccans. “Khoya” has a double meaning, “my brother” in dialectal Arabic and “jewel” in Spanish.

Its message is that

“Moroccan Jews and Muslims are brothers, share the same customs and must work together to revive this heritage,”

says El Baz. (52)

From a family originally from Tetouan (northern Morocco), she herself represents those Moroccan Jews steeped in Spanish culture, an influence that is reflected in the concerts El Baz gives.

The sound library includes two types of recordings: songs and music by popular Moroccan Jewish artists, collected in the field or in a commercial format, and recordings of stories of Moroccan Jewish families told by both Jewish and Muslim citizens.

‘’”Khoya” is still “incomplete,” notes Vanessa Paloma El Baz, however, explaining that many Moroccan Jews in Israel, Europe, and North America have recordings, videos, and photographs that could add to the collection, which already consists of hundreds of hours.

Gathering Moroccan Jewish memory “has not been easy,” she says, citing the reluctance of some families to hand over the recordings.

Will the work of Vanessa Paloma El Baz revive and reinvigorate interest in Moroccan Jewish music among Muslims and Jews worldwide and could ultimately be used as a bridge to the resurrection of the Andalusian vivre-ensemble and convivencia much-needed today in the time of religious turmoil and radical negativism. That is the question we all ask and the hope we all entertain. Amen.

You can follow Professor Mohamed Chtatou on Twitter: @Ayurinu

End notes:

- A feeling of belonging to Morocco in its religious and ethnic pluralism.

- B., Safia. ‘’Hassan II and the Tree Metaphor: A Reflection of the Plural Moroccan Identity’’, Dune Magazine, https://www.dunemagazine.net/eng-trans/hassan-ii-and-the-tree-metaphor Palacio, Ana. ‘’Feuilles en Europe, racines africaines’’, Libération, February 19, 2019, https://www.libe.ma/Feuilles-en-Europe-racines-africaines_a106237.html

- Chtatou, Mohamed. ‘’La diversité culturelle et linguistique au Maroc’’, Asinag 2, 2009, pp. 149-161. https://www.ircam.ma/sites/default/files/doc/asinag-2/mohamed-chtatou-la-diversite-culturelle-et-linguistique-au-maroc-pour-un-multiculturalisme-dynamique.pdf

- Chtatou, Mohamed. ‘’The Departure of Moroccan Jews to Israel Bitterly Regretted’’, Jewishwebsite, September 17, 2019. https://jewishwebsite.com/featured/the-departure-of-moroccan-jews-to-israel-bitterly-regretted/46551/

- Hachkar, Kamal. ‘’Tinghir-Jérusalem : Les échos du Mellah’’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LcZoLaMvaP0

- https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Morocco_2011.pdf

- Decter, Jonathan P. “<strong>A Myrtle in the Forest:</Strong> Landscape and Nostalgia in Andalusian Hebrew Poetry.” Prooftexts, vol. 24, no. 2, 2004, pp. 135-66. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2979/pft.2004.24.2.135. Accessed 31 Jul. 2022.

- Reynolds, Dwight. “The Music of al- Andalus: Meeting Place of Three Cultures”. A History of Jewish-Muslim Relations: From the Origins to the Present Day, edited by Abdelwahab Meddeb and Benjamin Stora, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013, pp. 970-984. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400849130-080

- Scheindlin, Raymond P. “Old Age in Hebrew and Arabic Zuhd Poetry”. Fierro, Maribel. Judíos y musulmanes en al-Andalus y el Magreb : Contactos intelectuales. Judíos en tierras de Islam I. Madrid : Casa de Velázquez, 2002, pp. 85-104. http://books.openedition.org/cvz/2726

- Abitbol, Michel. Les commerçants du roi Tujjar al-Sultan: Une élite économique judéo-marocaine au XIXème siècle. Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose, 1999.

- Guignard, Michel. “Les Musiques Dans Le Monde de l’islam : Un Congrès à Assilah (Maroc), 8-13 Août 2007.” Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie, vol. 21, 2008, pp. 269-86. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40240679

- Joseph Chetrit. “Music and Poetry as a Shared Cultural Space for Muslims and Jews in Morocco”, in Studies in History and Culture of North African Jewry. Proceedings of the Symposium at Yale University, April 25, 2010, Bar-Asher, Moshe & Steven D. Fraade (eds.), pp 65-102. https://www.academia.edu/8721510/Joseph_Chetrit_Music_and_Poetry_as_a_Shared_Cultural_Space_for_Muslims_and_Jews_in_Morocco_

- Benichou Gottreich, Emily. Jewish Morocco: A History from Pre-Islamic to Postcolonial Times. London: I. B. Taurus, 2021.

- Chetrit Joseph; Jane S. Gerber & Drora Arussy. Jews and Muslims in Morocco. Their Intersecting Worlds. Lanham, Maryland, USA: Rowman & Littlefield, 2021.

- Chetrit, Joseph. “L’identité judéo-marocaine après la dispersion des communautés : Mémoire, culture et identité des juifs du Maroc en Israël”. Abécassis, Frédéric, et al. La bienvenue et l’adieu | 2 : Migrants juifs et musulmans au Maghreb (XVe-XXe siècle). Casablanca : Centre Jacques-Berque, 2012, pp. 135-164. http://books.openedition.org/cjb/178

- Roda, Roda & Stephanie Tara Schwartz. ‘’Home beyond Borders and the Sound of Al-Andalus.Jewishness in Arabic; the Odyssey of Samy Elmaghribi’’, MDPI, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Aydoun, Ahmed. Morocco’s Jewish Music: La Musique Juive au Maroc. Rabat: Marsam, 2020.

- Gharbi, Mishka. ‘’ La musique juive du Maroc d’Ahmed Aydoun, un Beau Livre en trois langues’’, Le Courrier de l’Atlas, January 25, 2022. https://www.lecourrierdelatlas.com/la-musique-juive-du-maroc-dahmed-aydoun-un-beau-livre-en-trois-langues/

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Fenton, Paul B. ‘’La place de la musique andalouse dans le vécu du juif marocain’’, Horizons Maghrébins – Le droit à la mémoire, 43, 2000, pp. 82-86. https://www.persee.fr/doc/horma_0984-2616_2000_num_43_1_1904

- Guettat, Mahmoud. La musique arabo-andalouse. L’empreinte du Maghreb. Paris/Montréal : El Ouns/Fleurs sociales, 2000.

- Aydoun, Ahmed. Musiques du Maroc. Casablanca : Éditions Eddif, 1992.

- Campbell, Kay. ‘’Listening for Andalusian’’, Aramco World, Volume 62, Number 4 July/August 2011, https://archive.aramcoworld.com/issue/201104/listening.for.al-andalus.htm

- Reynolds, Dwight. “The Music of al- Andalus: Meeting Place of Three Cultures”. A History of Jewish-Muslim Relations: From the Origins to the Present Day, op. cit.

- https://www.womex.com/virtual/the_israeli_andalusit

- Elmaleh, Raphael David & George Ricketts. Jews Under Moroccan Skies: Two Thousand Years of Jewish Life. Bhilar, Maharashtra, India: Gaon Books, 2012.

- Bellaïche, Raoul. ‘’Salim Halali, le Prince du rythme’’, Je chante magazine n° 12, April 27, 2018. https://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/index2.php?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.jechantemagazine.net%2Fsingle-post%2F2018%2F04%2F27%2Fsalim-halali-le-prince-du-rythme#federation=archive.wikiwix.com

- Aous, Rachid. ‘’Aux origines du concept artistique judéo-arabe « Matrouz »’’, Horizons Maghrébins – Le droit à la mémoire, 50, 2004. pp. 110-117. https://www.persee.fr/doc/horma_0984-2616_2004_num_50_1_2204

- The Baqqashot (petition) is a religious practice maintained by several Jewish communities. It consists of gatherings that occur early on Sabbath morning, from 2-3 a.m. until the Shaharit prayer, in which the participants communally sing various piyyutim, which are titled Baqqashot. The practice developed, for the most part, in two geographical areas: the area of Allepo in Syria, and subsequently in other Syrian and Palestinian communities; and in Morocco. The Baqqashot are practiced during the winter, from Sukkoth to Passover, beginning on Shabbat Bereshit and until Shabbat Zekhor (the one prior to Purim) in Moroccan communities, and until Shabbat Hagadol (the one prior to Passover) in Allepian communities. Some of the main themes of the Baqqashot piyyutim are: the Kabbalistic perception of divinity; the meaning of the time of day in which the Baqqashot are sung (early morning); and the holiness and the value of the Sabbath.

- A piyyut (plur. piyyutim, Hebrew פיוט IPA: /pijút/ and [pijutím]) is a Jewish liturgical poem usually intended to be sung or recited during the service. Piyyutim have existed since the time of the Jerusalem temple. Most are in Hebrew or Aramaic and use a poetic structure such as an acrostic following the order of the Hebrew alphabet or spelling out the name of the author of the piyyut.

- El Haddaoui, Mohamed. La Musique judéo-marocaine : Un patrimoine en partage. Casablanca: La Croisée des chemins, 2014.

- Levitt, Joshua. ‘’The Moroccan Jewish Piyyut: A Judeo-Arabic Cultural Synthesis’’. Master of Arts in Liberal Studies (MALS) Student Scholarship. 110, 2001. https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol/11

- Elinson, Alexander. Looking Back at al-Andalus. The Poetics of Loss and Nostalgia in Medieval Arabic and Hebrew Literature. Brill Studies in Middle Eastern Literatures, Volume: 34. Leyden: Brill, 2009.

- Chétrit, Joseph. « Les pratiques poético-musicales juives au Maroc et leurs rapports avec les traditions andalouso-marocaines », Confluences Méditerranée, vol. 46, no. 3, 2003, pp. 171-179. https://www.cairn.info/revue-confluences-mediterranee-2003-3-page-171.htm

- Seroussi, Edwin. ‘’A Moroccan Synagogue Service’’, Jewish Music Research Centre, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, https://jewish-music.huji.ac.il/content/moroccan-synagogue-service

- Aous, Rachid. ‘’Aux origines du concept artistique judéo-arabe « matrouz »’’, op. cit.

- Ibid.

- www.matrouz.com/index.html

- Weich-Shahak, Susana. 2008. “Me vaya kapará: la haketía en el repertorio musical sefardí”, in La cultura judeo-española del norte de Marruecos. El prezente: estudios sobre la cultura sefardí, vol 2, edited by Tamar Alexander, and Yaakov Bentolila, pp. 291–300. Beersheva: Ben Gurion University et Moshe David Gaon Center for Ladino Culture.

- Elbaz, Vanessa Paloma Duncan. ‘’Jewish Music in Northern Morocco and the Building of Sonic Identity Boundaries’’, The Journal of North African Studies, 27:5, February 2021, pp. 1027-1059.

- Ibid.

- Abitbol, Michel. “De la tradition à la modernité : les juifs du Maroc”, Diasporas , 27, 2016, pp. 19-30. http://journals.openedition.org/diasporas/439; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/diasporas.439

- At the beginning of 1832, Delacroix, who had not traveled much until then, joined the delegation of the Count of Mornay sent by France to Morocco to Moulay Abd er-Rahman in order to ascertain the intentions of a country that had been alarmed by the French intervention in Algeria. Interrupted briefly by a stay in the “other East”, Andalusia, the trip to Morocco, which ended in June 1832, was one of the most important events in the life of the painter, who was an extremely active draughtsman (as evidenced by the famous Notebooks), feverishly collecting a treasure trove of images and sensations that were to nourish his art throughout his life.

- Mouhsine, Reda. ‘’Ces juifs chanteurs de chaâbi’’, Zamane, January 29, 2019, https://zamane.ma/ces-juifs-chanteurs-de-chaabi/

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Leafou, M’Barka. ‘’Chant de mariage juif au Maroc : étude sociolinguistique.’’ Thèse de doctorat en Etudes juives, sous la direction de Ephraïm Riveline. Soutenue en 2003, à Paris 8.

- Elmedlaoui, Mohamed. « Changement et continuité dans l’aḥwash des Juifs-Berbères. Remarques sur le travail d’ethnomusicologie de Sigal Azaryahu », Études et Documents Berbères, vol. 33, no. 1, 2014, pp. 207-211. https://www.cairn.info/revue-etudes-et-documents-berberes-2014-1-page-207.htm

- Elbaz, V. P. ‘’Connecting the Disconnect: Music and its Agency in Moroccan Cinema’s Judeo-Muslim Interactions’’, in Everett, Sami & Vince, Rebekah (eds.). Jewish-Muslim Interactions Performing Cultures between North Africa and France. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2020. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.56817

- Jeune Afrique/AFP. ‘’ Au Maroc, musiques et sons d’autrefois pour rappeler l’histoire juive du royaume’’, March 18, 2015. https://www.jeuneafrique.com/depeches/227719/politique/au-maroc-musiques-et-sons-dautrefois-pour-rappeler-lhistoire-juive-du-royaume/

- Chtatou, Mohamed. ‘’Al-Andalus: Multiculturalism, Tolerance and Convivencia’’, FUNCI, May 11, 2021. https://funci.org/al-andalus-multiculturalism-tolerance-and-convivencia/?lang=en

Thanks for the fine article. I was lucky enough to study oud with Samy ElMagribi in Montreal in the 1980s, and wrote a considerable part of my doctoral dissertation on songs of the Moroccan Sephardic women who had quite recently emigrated there. I’ve been back to Morocco quite often since my first trip in early 1972, most recently to give a concert in the historic Nahon synagogue of Tangier.