PRC Turns 70: Five Elements Of Its Grand Strategy – Analysis

By RSIS

As the People’s Republic of China prepares for its 70th birthday on 1 October, the issue of its grand strategy will be closely watched by political observers. To this end, both domestic and international objectives must be taken into account if we are to obtain a better understanding of what Beijing’s strategic intentions might be.

By Benjamin Tze Ern Ho*

On October 1, 2019, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) will celebrate its 70th birthday, thus marking another important landmark of modern China under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). While much of recent international interest in China has focused on its trade war with the United States and ongoing social protests in Hong Kong, the issue of what the PRC’s long-term intentions, and elements of its grand strategy, are equally important if we are not to miss the forest for the trees.

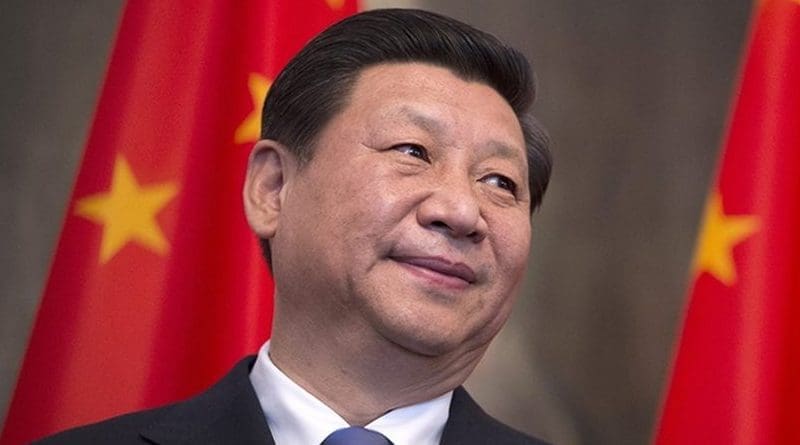

Indeed, if the previous five years under the leadership of President Xi Jinping are any indication, we are able to adduce certain broad trends that have emerged in the making of Chinese grand strategy.

Ensuring CCP Legitimacy

The first, and possibly the most crucial, is the need to ensure the legitimacy of the CCP to rule China. Given Chinese leaders criticism of Western democratic systems and the problems they generate, it is incumbent upon Beijing to demonstrate that its single party, authoritarian approach to governance is superior to the West.

This can only be so if Chinese leaders are able to evince that its social policies and governance have the support of the majority of the Chinese people. Due to the absence of parliamentary style elections in China, this is difficult to ascertain; hence, material prosperity and economic growth remains central to legitimising the CCP’s political rule. To this end, any slowdown of the Chinese economy would pose a challenge to the mandate of the CCP.

Widening International Support Base

Under President Xi, the Belt and Road (BRI) initiative has been one central feature of Beijing’s foreign policy. While a number of elements regarding the BRI remain unclear, particularly the economic viability and sustainability of BRI projects with other countries, one objective is certain: the BRI is conceived with the intention of widening China’s international support base through economic statecraft.

In this respect some modest progress has been made. The first BRI forum in May 2017 saw 29 foreign heads of state and representatives from 130 countries while the second BRI forum in April 2019 saw an increase to 37 foreign heads of state and participation from more than 150 countries.

This suggests that China would likely expend further efforts in the coming years to obtain greater international support for its global initiatives, especially among Western countries that possess strong relations with the United States such as the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada.

Increase International Isolation of Taiwan

The issue of Taiwan remains a core national interest and one which all Chinese leaders cannot be seen to make any compromise over. To this end, China – under President Xi – has been highly successful in the past few years. In 2013, Taiwan had official diplomatic relations with 22 UN member states, this number has now dwindled to 14 UN member states, with five of them coming in the past year, and two within a week in September (Solomon Islands and Kirbati).

While most of these recent countries are small Pacific and Oceanic states and are not considered major political players internationally, their strategic locations in key maritime waters proffer Beijing with increased opportunities to project international visibility while further eroding Taipei’s international presence and voice.

In the coming years, it is likely that China would further intensify international pressure on Taiwan, including attempts to shift the position of the Vatican (whose representation of an estimated 1.2 billion Catholics worldwide) presents a goldmine for Beijing’s leaders in terms of effecting strategic political and diplomatic presence.

Negate US influence in East Asia

In the minds of many Chinese leaders and political observers, the presence of the US in East Asia remains the biggest obstacle to China’s future prosperity and ability to project power regionally and internationally. Indeed, the Trump’s administration trade war is seen by many in Beijing as reflecting a more fundamental strategic decision by Washington policy-makers to constraint China’s rise in order to preserve US international primacy and leadership.

Major U.S. policies such as the “pivot to Asia” and the “free-and-open Indo-Pacific” in the eyes of China is conceived with one objective in mind: to keep China down and maintain American political influence in East Asia.

Notwithstanding the possibility of a change in administration come the next US elections in 2020, the perception from Beijing is that the US would continue to constrain China and hence the need for Beijing to find ways to negate American influence in the region. To this end, East Asia and Southeast Asia are seen as crucial theatres for Beijing to reduce American influence.

Global Rules and International Order

It is generally perceived by Chinese leaders and political observers that the rules of the international order were made so as to preserve the interests of the West. As such the problems faced by Western countries over the last decade or so were seen to be reflective of a historical trend whereby the influence of the West would be inevitably reduced. In contrast Asia and countries in the global South would assume greater say and share to the making of global order.

From this vantage point, China is seen as being the flag-bearer of such a new system and one which possesses the deepest resources with which to challenge American dominance. Indeed China’s presence is ubiquitous in most if not all major global institutions and forums and Chinese representatives are now far more vocal in stating and arguing Chinese demands and interests where they arise.

In 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed that the Chinese people have stood up, thus consigning the trauma and tragedy of its past to history. Today, China’s political worldview is far different from that of its early years as a far more confident China takes its place on the global stage. Where Beijing will go and how many will follow will be the test of its global influence and the persuasiveness of its grand strategy.

*Benjamin Tze Ern Ho is a Research Fellow with the China Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore.