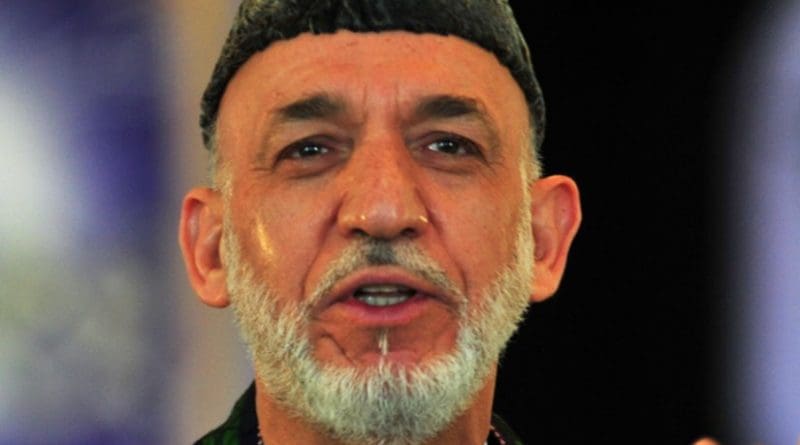

Karzai’s Unrealistic Decree: Banning Private Contractors In Afghanistan

In August 2010, Afghan President Karzai ordered all the private security contractors in the country to close down their operations by January 1, 2011. While most analysts considered the deadline too near and the decree imprudent, some welcomed the move. Rolling back from the stipulations of the previous decision, on October 17, 2010, the Afghan government announced that private security firms that are responsible for the protection of embassies and military bases could continue their operations. Following this, on October 27, Karzai decided to extend the deadline for the ban.

The PMCs operating in Afghanistan have recently been in the news for all the wrong reasons. The report titled, ‘Warlord, Inc.: Extortion and Corruption along the U.S. Supply Chain in Afghanistan’ of the US House of Representatives released in June this year exposed the perils of Washington’s policy of outsourcing security roles in Afghanistan. The report brought out the disturbing aspects of the contentious practice of hiring private contractors in war zones like Afghanistan.

Securing and maintaining the supply chain in Afghanistan has been one of the most challenging tasks for the U.S. forces and therefore presents numerous difficulties in conducting military operations and offering logistical support to over 200 forward operating bases dotted around the region. Consequently, this function was outsourced to private contractors. The main contract sustaining the U.S. supply chain in Afghanistan is Host Nation Trucking, a contract worth $2.16 billion, which was divided among eight Afghan, American, and Middle Eastern companies. Such a move led to grave consequences not premeditated.

To ease their operations and ensure safety, the private contractors ‘subcontracted’ warlords that may be susceptible to attacking them. This unintentionally stoked the practice of bribing warlords who maintain private armies and the money proved to be an important source of funding for the insurgents. Statistically, a third of the costs of logistics in Afghanistan are spent on paying protection, bribery and safe passage fees. The U.S. Congress recently voiced its concerns about the perils of PMCs and has sought to develop standards for PMCs and ensure greater accountability. However, it is important to note that complete execution of the plans could take years.

Even after all these odds and qualms about the effectiveness of the PMCs, the banning of the PMCs in Afghanistan as promulgated by Karzai seems highly impractical owing to numerous reasons. The primary reason is the unpreparedness of the Afghan security forces and the burgeoning insurgency in the country. The nature of the insurgency on the ground is much more complex. A parallel Tier 3 Taliban system is operating in numerous provinces and sometimes local warlords or local frustrations result in uprisings. The present preparedness of the Afghan National Police or the National Army is nothing close to the levels of preparedness needed to undertake roles that are currently being performed by the PMCs. Considering Kabul’s reliance on PMCs and the highly complicated insurgency, operations without the involvement of PMCs would only lead to a vacuum. This would pave way for an increase in the number of insurgent attacks on Afghan soil, further exacerbating the situation.

Further, the move would negatively affect the lives of numerous Afghan nationals (in range of 15,000 to 20,000) who depend of the industry for their living. It is important to note that under the decree, foreigners in the industry would lose their residency permits and Afghan nationals would be allowed to apply through the interior ministry for jobs in the Afghan Police force. While this move may seem reasonable, a sudden shift would be resisted by the nationals who were working for PMCs. This will be primarily because the salaries offered to Afghan forces are drastically low as compared to the salaries of the PMCs. Further, the immediate vacuum would worsen the security situation which may also delay the international developmental projects.

Another issue that makes the immediate ban unrealistic is the fact that most PMCs are owned by powerful Afghans. To illustrate, the owners of many private security firms have their family links with President Karzai. Therefore, the widespread nature and involvement of high profile Afghans in the business makes the move highly unlikely to materialise. As stated above, the Afghan government softened its stance on the ban and allowed the functioning of few PMCs in the region. However, as the time for the closing of operation nears, one can hope to have numerous interpretations of the decree and terms of leniency from the Afghan government. It would not be highly unlikely to see the Afghan government picking and choosing the PMCs it wishes to grant permission for operations. Also, this may indirectly purge the competition which the powerful Afghans tend to face in the business.

Moreover, while it is tougher to operate in Kabul without a license, the illegal contractors are placed outside Kabul, where the reach of the authorities is quite limited. Also, most of the PMCs outside Kabul do not work for the U.S. Government but offer their services to ‘other customers’. With limited influence of the governmental authorities outside Kabul, ensuring that the operations of illicit PMCs are ceased is rather ambitious.

What remains important at this juncture is to embark on immediate steps to bring the shift from PMCs to national forces in slow and planned in phases. A smooth transition would be realistic and would also ensure that the security environment of the country is not hampered. It is also important to define the role of private contractors and review the history of the contractors before offering them contracts and undertake periodic auditing.