Bangladesh Papering Over The Cracks At Home And Abroad – OpEd

In a recent interview with DW, Bangladeshi Foreign Minister AK Abdul Momen asserted that Dhaka’s objective is to “get along with everybody”. Despite the ongoing saga surrounding Rohingya refugees from Myanmar and widespread protests against a spate of deals agreed earlier this month with New Delhi, Momen assured viewers that the Bangladeshi government is successfully balancing relations with all parties. (Note: for a response to this article, read: Letter To Editor From Bangladesh’s Ambassador)

However, his comments do not align with the reality after a month which can only be described as turbulent in Bangladeshi foreign relations. Perhaps even more concerningly, the trouble abroad has only served to highlight simmering discontent at home, as Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s government comes under increasing fire for its suppression of dissent and censorship of the media.

Neighbourly disputes

One of the biggest crises facing Dhaka is the displacement of some 900,000 Rohingya from nearby Myanmar, the vast majority of whom have found shelter in the refugee camps in Bangladesh. While Momen has said he expects Myanmar to honour its promise of taking back its citizens with assurances of a safe and dignified reception, they’re currently caught in a no man’s land of uncertainty—with no guarantees that Naypyidaw would respect their rights if they returned to Burmese soil. In the meantime, Rohingya refugee children are prohibited from attending school and Dhaka’s plans to move around 100,000 of the displaced to a remote offshore island with a high cyclone risk have been met with criticism and concern.

Elsewhere, a rare incident—a reportedly accidental exchange of fire between the Indian Border Security Force (BSF) and the Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB), 650 yards into Bangladeshi territory—shone a spotlight on the two countries’ relationship only weeks after Hasina had met with her Indian counterpart Narendra Modi. During Hasina’s four-day visit to India at the beginning of October, she and Modi signed seven bilateral documents of cooperation, in an ostensible demonstration that all is well between the two nations.

Discontent highlighted by horrific university killing

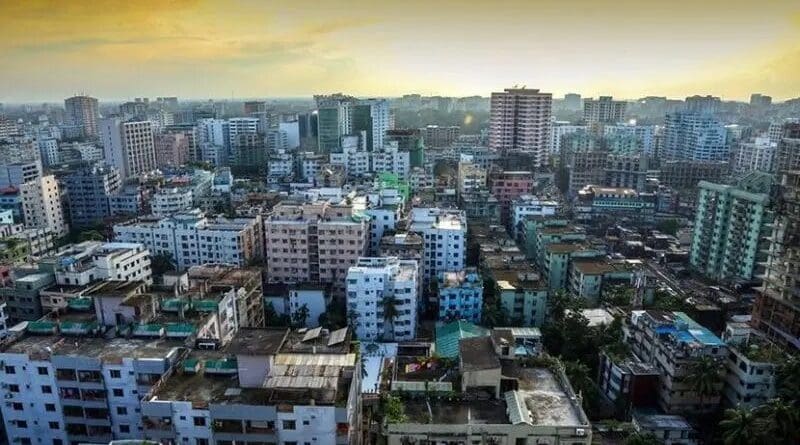

Those agreements immediately came under fire from opposition politicians, who claim the deals (including one to share water from the Feni River) prioritize Hasina’s personal interests over national ones and disadvantage everyday Bangladeshis. Those concerns were echoed by Abrar Fahad, a 22-year-old university student at the prestigious Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET) in Dhaka. Tragically, the young man was brutally beaten for expressing his views, with his injuries eventually proving fatal. Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL), the student wing of the ruling Awami League party, has been implicated in the attack, with at least 13 people arrested and six more wanted for questioning.

The tragedy sparked mass protests led by university students and Hasina herself has denounced those responsible, but the actions of the authorities do not match her condemnatory remarks. According to students at BUET, incidences of such intimidation and bullying are rife at the University, while protests this summer over road safety in the country were also marred by BCL brutality. In June, demonstrators were attacked with sticks, bricks and machetes; their assailants are yet again believed to belong to the Awami League’s student body. That incident also served to highlight the flagrant censorship techniques employed by Hasina’s government, after prominent photographer Shahidul Alam was detained just hours after disparaging the powers that be on television and the internet. Although he was later released and his trial ultimately dropped, that only came after 107 days of incarceration and alleged torture.

Censorial and corrupt

While the detention of Alam might be the highest profile use of the controversial Digital Security Act, it’s far from the only instance of government censorship of dissenting voices. Indeed, a Human Rights Watch report from April 2018 found 1,271 cases where the deliberately vague legislation has been used to apprehend and silence voices in the media. At least 19 journalists were charged under the Act in 2017 alone. The clampdown has forced many reporters to either self-censor their work or flee the country and continue to expose its corrupt underbelly from abroad.

Even the legitimacy of Hasina’s government itself has been called into question. Hasina was re-elected in December 2018 by winning an implausible 96% of the vote, after a campaign marked by suppression and a polling day tarnished with widespread violence, including 17 deaths. In the run-up to the vote, Hasina had her main political rival Khaleda Zia arrested on embezzlement charges which Bangladesh’s opposition have called politically motivated, banned more than 18,000 websites and blocked 54 news outlets. Countless other red flags – from firing thousands of factory workers for marching for decent wages to obstructing the appearance of a world-famous author at a public event – signal the country’s disconcerting trend.

Foreign Minister Momen seemed to treat the election irregularities with bizarre nonchalance, telling journalists that “it does not matter much” that the Awami League faced accusations of massive vote rigging. The December 2018 polling day, Momen opined somewhat callously, “was a unique, beautiful election. Very few people died.”

Momen fooling no-one

While Momen’s most recent appearances in the mainstream media may be intended to send the message that all is well both at home and abroad, the reality of the situation is in stark contrast to his words. Hasina may purport to “get along with everybody” – especially when that involves neighbouring powers that are bigger and more powerful than herself – but it certainly doesn’t extend to those inside her own country who happen to share different views. Unless the pervasive culture of censorship and strongman tactics can be stamped out from Bangladeshi politics, the country’s populace will continue to suffer.

*Chloe Durham is a writer and consultant based in Paris.