How Trump Tariff Wars Worsen US Trade Deficit – Analysis

Since 2018, Trump’s trade wars have made US trade deficit only worse, while hurting the poorest economies the most and penalizing global prospects.

According to the new IMF outlook, global growth is forecast at 3.0% for 2019. That’s the lowest since the global crisis of 2008-9. The decline is largely due to the US tariff wars, which have contributed to the projected slowdown in the US and China.

Due to the global slowdown, world growth prospects now hover at levels where they were last amid the darkest moments of 2008/9.

Trump tariffs widen US trade deficit

Recently, international media reported that, in August, the politically sensitive US goods trade deficit with China decreased 3.1% to $32 billion relative to previous month. Yet, US trade deficit actually widened to almost $55 billion in August. While exports rose 0.2%, imports increased more than twice as fast at 0.5%.

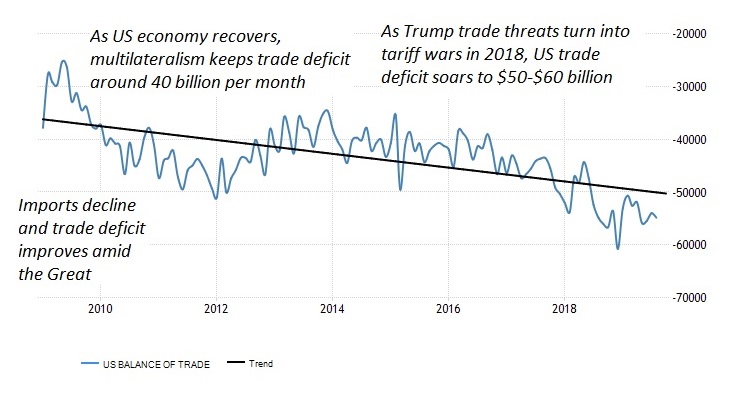

Unfortunately, monthly data does not reflect secular trends and overall deficit trend matters. In longer view, US trade deficit improved during the Great Recession, when imports declined. As the economy recovered in the early 2010s, multilateralism still kept trade deficit around $40 billion per month.

The change came when President Trump’s trade threats turned into tariff wars in 2018. Since then, the trade deficit has been around $50 to $60 billion per month, while the trend line (in black) suggests progressive deterioration (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The Widening of US Trade Deficit

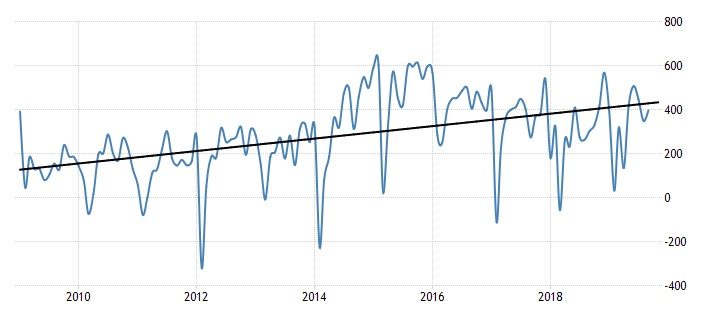

What about China’s trade surplus? In September, Chinese exports declined 3.2% over a year earlier, which the White House’s trade hawks saw as progress. Nevertheless, imports to China plunged more than twice as fast at 8.5%. That’s what happens in times of trade friction and uncertainty; import growth declines.

The net effect? China’s trade surplus actually widened to $40 billion in September. In the long view, the trend line (in black) the relative strength of the trade surplus, even amid the US tariffs (Figure 2).

Figure 2 China’s Trade Surplus

The bottom line? The Trump tariff wars are working – if the strategic objective is to further weaken the US trade deficit and to deepen trade friction with China and other trading nations particularly in developing Asia.

How US tariffs hurt most the poorest economies

Worse, the Trump tariff wars are harming the most the poorest economies. In the postwar era, Washington’s trade, investment and financial ties broadened and deepened mainly with other major advanced economies in Western Europe and Japan. The postwar economic miracles of these rich economies did not support the rise of the Third World – developing Asia, Africa, Middle East and Latin America.

In the past decade or two, China’s economic ties have broadened and deepened dramatically not just with major advanced economies, but particularly with emerging and developing world regions. Moreover, the One Belt and Road (BRI) initiative seeks purposefully to accelerate modernization in poorer economies in which industrialization was never completed or has barely begun.

The implication is critical. Since China’s contribution to the rise of the poorer economies is now vital, any collateral damage that US tariff wars affect in China, whether directly through trade and investment abroad or indirectly through the reduction Chinese output potential, will harm disproportionately the poorest economies in the world – through their external trade ties and multiplier effects in their domestic economies.

The longer the US tariff wars prevail, the broader the collateral damage will be in emerging and developing economies.

Diminished global prospects

In 2008-9, the global crisis was contained by massive fiscal stimulus packages, ultra-low rates and, when that proved inadequate, rounds of quantitative easing.

Now, a decade after the crisis, central banks’ rates remain ultra-low and most continue asset purchases, whereas soaring debt levels limit new fiscal injections.

The IMF projects growth to pick up to 3.4% in 2020. That, however, is predicated on improvements in a number of emerging economies in Latin America, the Middle East and developing Europe, which would require a trade recovery. And the latter is not likely as long as the misguided US tariff wars prevail.

The Trump administration’s tariff wars are the worst policy mistake in the postwar era. They will improve neither US trade balance nor global economic prospects. They have already made both worse.

A shorter version of the commentary was released by China Daily on October 31, 2019