Getting To The Bottom Of Hungary’s Russia Spying Problem – OpEd

A flash drive containing classified data, reportedly discovered hidden in the anus of an agent trying to cross the Ukrainian-Hungarian border, illustrates how Hungary has become a hub for Russian spying.

By Szabolcs Panyi

In late November, at a Ukrainian-Hungarian border crossing checkpoint, Ukrainian special forces armed with machine guns and rifles arrested a suspected Russian agent just as he was trying to cross the state border.

The man was a former employee of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine, who, according to the Ukrainian security agency SBU’s statement, “collected classified information about the leadership and staff of the law enforcement agencies of Ukraine. The man planned to personally transfer the data to the Russian Embassy in Budapest on a flash drive”.

The stolen data was partly personal information on SBU and GUR (military intelligence) officers, leaders of the Azov movement, and on military personnel of the 72nd mechanized brigade of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. The other part of the data was sensitive military information on Ukrainian army bases, arsenals, warehouses and their locations.

Ukrainian Telegram channels posting video footage of the arrest mostly focused on an unconfirmed but understandably newsworthy detail: that the Russian agent had allegedly hidden the USB drive in his anus. However, the most interesting information of the SBU’s statement was about the role of Hungary and the Russian embassy in Budapest, which was apparently considered by the protagonists as a safe place for arranging such meetings.

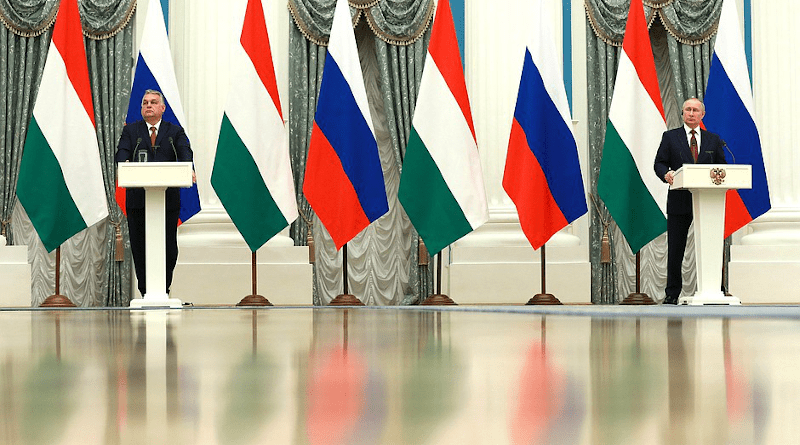

The pro-Kremlin attitude of Viktor Orban’s government – even after the invasion of Ukraine – is well documented. Most recently, together with a colleague of mine at Direkt36, we investigated the Hungarian government’s response to the war and motivations behind the policy to maintain a close relationship with the Kremlin. What we found is that through Hungary’s dependency on Russian fossil fuels, Moscow has essentially taken the Orban government hostage.

However, Hungary’s softly-softly approach towards a belligerent Russia has already reached a level where economic necessities, mostly its dependency on Russian oil and natural gas, do not entirely explain the Orban government’s decisions. A laissez-faire approach towards hostile intelligence activity, attempts to undermine the EU’s sanctions regime against Russia, and slowing down if not hindering NATO responses are starting to create visible problems for the whole Western alliance.

Budapest – where Russian spooks feel safe

It is not only a random Ukrainian traitor trying to pass classified information to his Russian handlers in Budapest who sees Hungary as a safe haven.

On November 10, together with Ukrainian OSINT group Molfar, we revealed details about the Hungarian ties of Russian spy chief Sergey Naryshkin’s family. Molfar obtained an official document about the Budapest home address of Naryshkin’s son, Andrey, who, together with his wife and kids, obtained Hungarian residency through the country’s controversial golden visa scheme. This came with a visa that is valid not only for Hungary, but also the rest of the Schengen Area inside the EU.

The latter was already reported in one of our previous joint investigations with 444.hu and Novaya Gazeta back in 2018. However, it was previously unknown that Andrey Naryshkin’s home address was registered among the company property of a businessman who, according to his own words, “has been friends for more than ten years” with Antal Rogan, head of the Prime Minister’s Cabinet Office.

Rogan is not only currently the most powerful member of Viktor Orban’s cabinet, but he is also the minister in charge of overseeing the country’s increasingly powerful and politicised national security agencies – including the counterintelligence agency tasked with going after Russian spies.

More interestingly, an official statement from Orban’s cabinet office revealed that Hungarian counterintelligence only found national security risks associated with Naryshkin’s son in 2020 – four long years after Sergey Naryshkin had become head of the SVR, Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service. Hungarian counterintelligence then tried to revoke the family’s Hungarian residency permit. However, due to appeals by the Naryshkins and lengthy court proceedings, the revocation is still not in effect. These revelations have yet again shown how little Hungary’s national security agencies care and do against Russian infiltration.

And this has not been the only worrying case in recent months. In March, we also revealed that Russian hackers working for the FSB and the GRU have been penetrating the Hungarian Foreign Ministry’s IT networks and internal communications in multiple waves since at least 2012. Viktor Orban’s government has never disclosed these incidents to the public despite their gravity. The latter is shown by the fact that the latest Russian hacking occurred in mid-2020 and remained an active infestation even many months after the start of the war in Ukraine in February 2022. Hungary’s allies were puzzled by the mild – or more precisely non-existent – Hungarian government reaction to the hackings.

There was another measure that Orban’s government decided not to take against Russia, even after the war began. While almost every EU member state has expelled Russian spies operating under diplomatic cover, Hungary opted not to follow suit.

As Peter Kreko, senior fellow at CEPA and director of the Budapest-based Political Capital Institute, pointed out during a hearing in the European Parliament, “the staff of the Russian embassy in Budapest is on the rise. According to official data, there are currently 56 accredited diplomats working at the embassy, up from 46 a year ago, risking that Budapest is becoming one of the new spy hubs in the European Union. For comparison: on May 31 this year, there were six diplomats in Prague, 13 in Warsaw and three in Bratislava.”

No wonder there is Russian capacity in Budapest to receive carefully hidden flash drives from Ukraine.

Liability for the EU and NATO

One could argue it is up to the Hungarian government to pursue the kind of Russia policy it wants, even when it comes to deciding on how or how not to react to hostile intelligence activity on its territory – or even inside one of its ministries. However, as a member of both the EU and NATO, whatever threats there are to Hungarian national security are also threats to the whole Western alliance.

For example, Russian spies working under diplomatic cover in Budapest do not necessarily target the host country with all kinds of intelligence operations. It is a known modus operandi of Russian intelligence that they station their intelligence officers in other countries, not where they actually operate. In this regard, Hungary’s role is more of a regional logistics hub, from where operations against neighbouring countries – primarily the Balkans – are organised and carried out.

This means, for example, they use Hungary to rent cars, establish safe houses, or to exchange information and money with assets. Former Austrian military officer and Russian spy colonel Martin Muller used to meet his handler in the popular bath town of Heviz, while two GRU agents on their way to blow up an ammunition depot in Vrbetice in the Czech Republic stopped over at the Russian embassy in Budapest on their way.

Russian hackers infiltrating the Hungarian Foreign Ministry also did not stop at accessing only Hungary-related information. First, they also broke into the secured internal communications network called Protected Foreign Network (Vedett Kulugyi Halozat) of the Hungarian MFA where NATO and EU-related material with ‘restricted’ and ‘confidential’ classification are also regularly transmitted. Second, they used the infected computers to launch further attacks – now disguised as Hungarian governmental IP addresses – against the US.

One would think that, after the exposure of all these risks to EU and NATO national security, the Hungarian government would try to overcompensate – or at least reassure their allies in any way possible. Quite the opposite.

Two weeks before the outbreak of the war, on February 10, Hungarian Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto publicly refused to accept more NATO troops in Hungary, hindering a joint attempt aimed at deterring Russia. Szijjarto claimed that such reinforcements would only contribute to escalating tensions; instead, he urged “the international community to do its best in order to avoid a return to the Cold War”.

Hungary eventually agreed to take in more NATO soldiers, but the invasion had already started by then. However, Orban’s government openly refused to give any kind of military support to Kyiv, not only ruling out direct help with sending over Hungarian military equipment but also banning weapons transfers crossing Hungary’s territory to Ukraine. Of course, Hungary also made it clear that it strictly opposes any NATO no-fly zone initiative over Ukraine.

Then there is the issue of Finland and Sweden’s NATO accession. Although the Hungarian foreign minister already submitted the accession treaties to Hungary’s parliament in July, the parliamentary supermajority of Orban’s Fidesz party – which, in multiple cases in the past, was willing to hold a vote and pass any kind of legislation in a matter of 24 hours – has been stalling them ever since.

When Hungarian opposition parties tried to hold an immediate vote on accession, Orban’s MPs voted against, killing their initiative. Thus, Hungary has became the very last EU member state – and the last NATO member state alongside Turkey – not to accept the two Nordic countries into the alliance that can protect them from Russian aggression. Recently, Orban claimed that parliament will finally vote on the treaties next year – which, knowing the regular schedule of Hungary’s parliament, would mean February 2023 at the earliest.

However, Finland and Sweden at least received a partly positive message from Hungary. Another NATO hopeful, Ukraine itself, has been mucked around by Hungary for many years within NATO. Orban’s government has been blocking high-level Ukraine-NATO meetings on ministerial levels since 2018. The pretext has been that Ukraine is disrespecting minority rights, including those of the Hungarian community in the Transcarpathian region, and this is a way for Hungary to try pressure Kyiv to change course.

Many other NATO members tend not to believe this explanation and, in February 2020, a dozen of NATO allies officially protested in Budapest by handing over a démarche (written protest letter) to the Hungarian Foreign Ministry. So it came as no surprise that Hungary has also been one of the two Central and Eastern European countries – the other being Bulgaria – not to support Ukraine’s NATO bid in a recent joint statement signed by the countries’ presidents. Most recently, Hungary vetoed Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba’s full participation at a NATO foreign ministerial meeting in Bucharest, shocking many NATO allies.

Unsurprisingly, the partly invaded country’s NATO membership currently seems like a long shot, if not downright impossible. For Ukraine, EU membership and closer cooperation with the bloc is far likelier. Yet Orban has an answer to those efforts, too: he just refused to support an EU plan to provide Ukraine with €18 billion in budgetary assistance next year.

Even so, Orban’s latest disruptive moves could be a real game-changer in a different way, if they make the Western alliance finally accept that Hungary has become NATO’s weakest link.