East Africa Using Large Amounts Of ‘Highly Hazardous’ Pesticides To Fight Locust Plague – Analysis

By Mongabay

By Leopold Salzenstein*

Swarms of locusts tens of kilometers wide have threatened to devastate crops in East Africa since late 2019, putting some 32 million people at risk of going hungry.

The desert locust infestation, described by the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in 2020 as a “scourge of biblical proportions,” is the worst the region has seen in decades, according to humanitarian groups. In Ethiopia, the triple threat of locusts, floods and COVID-19 threatened to tip the region into a humanitarian crisis.

To combat the emergency, governments have resorted to spraying large tracts of land with some 2 million liters of insecticides over almost 2 million hectares (5 million acres), since the beginning of the outbreak in December 2019, prompting concerns over the potential health and environmental impacts.

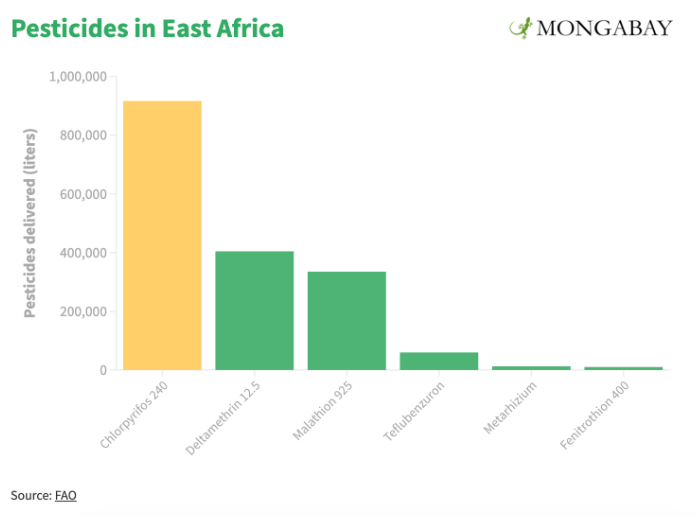

A new Mongabay analysis of FAO pesticide purchase data can reveal that the concerns may be well-founded, as 95.8% of the pesticides delivered to East African nations over this period are scientifically proven to cause serious harm to humans and non-target organisms such as birds, fish and bees.

Though none of the six pesticides used in East Africa are classed as “highly hazardous” by the World Health Organization, chlorpyrifos and fenitrothion are considered “moderately hazardous” and malathion “slightly hazardous.”

The Pesticide Action Network (PAN), a campaigning group, lists all three compounds as “highly hazardous.” They are considered acutely toxic, a cholinesterase inhibitor, a carcinogen, a groundwater pollutant or reproductive or developmental toxicant.

According to a report by EcoTrac, an environmental consultancy, three are highly toxic to fish and mammals and two are highly toxic to birds.

Contacted by Mongabay, the FAO said it takes precautions to limit the risk of pesticides causing harm to humans and the environment.

If these toxins are to be used at all, people are advised to vacate the area for several days while spraying takes place, according to the FAO. The pesticides should be sprayed at ultra low volume, with a buffer zone of 1,500 meters (nearly a mile) from ecologically sensitive areas when sprayed by plane, and 100 meters (330 feet) when sprayed on foot. Locust control staff should wear personal protective equipment, and wells and beehives should be covered during spraying.

However, according to Silke Bollmohr, an environmental consultant at EcoTrac, safety measures are not always followed in East Africa. “Conservancies up in the north [of Kenya] were reporting that the sprayers didn’t inform the communities. There was no information about what pesticide had been used and not always a timely warning to protect water [sources], beehives and livestock,” she said.

In Ethiopia, two spraying planes and one helicopter have crashed since October 2020, raising further concerns about the risk of large amounts of toxic pesticides being released.

The case against organophosphates

Most of the pesticides used in East Africa are organophosphates, a type of chemical developed by German chemical conglomerate IG Farben for the Nazis during World War Two that includes sarin gas. “[They] suppress an enzyme, called Cholinesterase (AChE), which regulates brain impulses, like nerve impulses, throughout the body,” Patti Goldman, an attorney at EarthJustice, a U.S.-based environmental litigation group, told Mongabay.

Organophosphates kill locusts by attacking their nervous system, but they do not distinguish between pests and other species. While cases of acute poisoning are rare when used at ultra-low volumes, organophosphates have recently come under heightened scrutiny due to their potential long-term impacts on human health.

Studies by Columbia University, Mont Sinai School of Medicine and the University of California, among others, have connected organophosphates with brain damage in children and fetuses. Studies have identified statistically significant reductions in IQ, loss of working memory, autism, attention deficit disorder, and motor coordination problems associated with exposure.

“Using [organophosphates] for locust control can present a health risk, especially for vulnerable groups like pregnant women and children,” said Helle Raun Andersen, associate professor at the University of Southern Denmark’s Institute of Public Health.

Chlorpyrifos is one of the most harmful substances currently used against locusts. The pesticide, also classified as an organophosphate, has been the subject of major controversies in recent years.

In 2016, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) found there was no safe use for chlorpyrifos, as effects had been recorded at the lowest observable dose. After proposing to ban the substance during President Barack Obama’s second term in office, the EPA reversed its decision during the Trump administration. Shortly after taking office, the Biden administration announced it intended to review the ban. “At some point, it’s going to be banned,” Goldman said. “It’s just taking some time.”

In the EU, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) reported in 2019 that chlorpyrifos presents “concerns related to human health, in particular in relation to possible genotoxicity and developmental neurotoxicity.” And in 2020, the European Commission banned the use and sale of chlorpyrifos in the EU.

That same year, the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) suggested adding the substance to the list of persistent organic pollutants (POPs), a set of chemical substances recognized as a serious global threat to human health and ecosystems.

Since the start of locust plague in early 2020, 916,656 liters (242,155 gallons) of chlorpyrifos have been distributed in East Africa, according to FAO data. In Ethiopia alone, the FAO distributed 537,000 liters (141,860 gallons) of chlorpyrifos, while the government purchased another 145,000 liters (38,300 gallons). In total, half of all anti-locust pesticides delivered to East Africa since the beginning of the infestation contained chlorpyrifos.

“Chlorpyrifos has been used more than I would like,” said Graham Matthews, the former chair of the Pesticide Referee Group (PRG), a body of experts advising the FAO on the efficacy and environmental impact of anti-locust pesticides. “But it has been available and … it may have been less expensive than alternatives,” he added.

The PRG last met in 2014, when it provided the FAO with a list of 11 pesticides recommended for use against locusts, in order of priority. Organophosphates are ranked last and the PRG recommended their use only as a “last resort [method], when rapid control is needed to protect agricultural crops in the immediate environment of a locust population.”

“[Organophosphates] are problematic pesticides, no question about it,” Mark Davis, who directed the FAO’s Pesticide Management Programme from 2007 to 2015, told Mongabay. “They are amongst the most poisonous pesticides when it comes to human exposure and exposure of non-target organisms in general. They are not pleasant things.”

For Davis, however, the current use of organophosphates against locusts in East Africa is justified. “The use of these chemicals is a signal that the monitoring and early control measures have failed,” he said. “[Adult locusts] are big creatures, they are not easy to kill. [The FAO and local governments] need heavy weapons to bring them down.”

In a statement to Mongabay, an FAO spokesperson said: “Heavy rains tipped the balance by providing favourable conditions for the Desert Locust breeding on huge areas, and prevention is no longer feasible. This put the current situation into emergency status.

“Right now we are dealing with numerous swarms. Under such conditions, to prevent crop and pasture damage, the most appropriate tool is the use of conventional pesticides, which provide fast and efficient control.”

But as the crisis drags on into 2021, environmentalists have started to poke holes in this logic.

In Kenya, Greenpeace questioned the use of toxic pesticides in locust control operations. In June 2020, a group of 11 NGOs raised their concerns in a letter to Kenya’s Ministry of Agriculture.

Could biopesticides offer an alternative?

Not all pesticides currently in use are harmful to non-target organisms. Some countries, such as Somalia, primarily rely on biopesticides and insect growth regulators (IGRs), which present few concerns for public health and the environment.

The preferred alternative to organophosphates is a biopesticide based on a fungus called Metarhizium acridum. The fungus targets locusts by competing with them for water and nutrients and is not toxic to humans or other species.

Locusts start weakening three to four days after being contaminated with M. acridum. Maximum mortality is reached after about two weeks as the fungus continues to produce spores on dead locusts and can easily spread to the entire swarm. Since the start of the 2020 infestation, the FAO and national governments have purchased 12,730 liters (3,363 gallons) of biopesticides, less than 1% of the volume of organophosphates purchased.

Other alternatives include less harmful pesticides, such as IGRs, favoring predators of the locust, and spraying natural locust repellents, such as neem oil. However, these alternatives tend to be less efficient against mature swarms and have been only sporadically used in East Africa since 2020. IGRs represent 3.4% of the pesticides reported by the FAO.

‘We are stuck with what we have’

While the PRG is scheduled to meet in mid-April, whether or not organophosphates will remain on the list of recommended substances remains uncertain. “It is less likely that Chlorpyrifos … will be recommended if a safer product can be used,” Matthews, the former PRG chair, told Mongabay. “No one wants to use products classified as highly hazardous.”

But the situation shows little sign of abating. In recent years, locust infestations have been sporadic and interrupted by large periods of recession, which prevented scientists from testing new locust control pesticides. “The problem with locusts having long recession periods is that little new data is available,” Matthews said.

In 2014, the FAO questioned why no new insecticides had been sufficiently tested to confirm effective dose rates against locusts. “[Locust control operation] is a relatively small and unpredictable market. Companies will not invest in developing new chemicals, so basically we are stuck with what we have,” Davis said.

Will recent controversies over chlorpyrifos and organophosphates make a difference? In 2015, the PRG already warned that “organophosphate insecticides have globally come under heightened regulatory scrutiny because of health and environmental risks. Their use in locust control may be restricted in the near future.” Such restrictions will come too late for those affected by the recent mass spraying in East Africa.

A new locust wave looms

“Good progress has been achieved” against the locusts, according to the FAO. The heavy use of toxic pesticides, combined with forecasts for below-normal rainfall, is likely to bring the threat down in the coming months.

But the respite may not last. Heavy rains could fuel a third wave of infestation, while conflicts in Yemen, Somalia and northern Ethiopia complicate spraying operations. COVID-19, which already hampered the response in 2020, further adds to the challenge.

“Globally, more than 2.8 million hectares [6.9 million acres] were treated in 2020,” Keith Cressman, the FAO’s senior locust forecasting officer, said in a recent podcast published by the organization. “The problem is that the weather continues to favor the locusts.”

Warming seas mean stronger and more frequent cyclones, more rain and favorable conditions for locust breeding. With climate change making locust-friendly weather increasingly likely, relying on harmful pesticides could prove unsustainable in the long run. By strengthening locusts’ resistance to pesticides and killing their natural predators, the use of toxic pesticides could even worsen the next crisis.

*Source: This article was published by Mongabay

Citations:

Von Ehrenstein, O. S., Ling, C., Cui, X., Cockburn, M., Park, A. S., Yu, F., … Ritz, B. (2019). Prenatal and infant exposure to ambient pesticides and autism spectrum disorder in children: Population based case-control study. BMJ, 364, l962. doi:10.1136/bmj.l962

Engel, S. M., Wetmur, J., Chen, J., Zhu, C., Barr, D. B., Canfield, R. L., & Wolff, M. S. (2011). Prenatal exposure to organophosphates, Paraoxonase 1, and cognitive development in childhood. Environmental Health Perspectives, 119(8), 1182-1188. doi:10.1289/ehp.1003183

Rauh, V. A., Garfinkel, R., Perera, F. P., Andrews, H. F., Hoepner, L., Barr, D. B., … Whyatt, R. W. (2006). Impact of prenatal chlorpyrifos exposure on neurodevelopment in the first 3 years of life among inner-city children. Pediatrics, 118(6), e1845-e1859. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0338