Sumo As A Religious Rite In Japan

By UCA News

The country’s national sport was originally conceived as a ritual to entertain the gods of Shintoism.

By Cristian Martini Grimaldi

We are all very much familiar with the Japanese national sport of sumo. The athletes’ topknots, the bowing to each other before the matches and the iconic foot stomps (shiko) inside the ring are recognizable features. But as foreigners we rarely understand the deep religious meaning of it all.

Before we delve into the nature of the sport, it is important to understand the concrete dynamics at play inside a sumo training facility.

We are in the Koto district of Tokyo, one of the most important sumo (heya) schools in all of Japan. Here the wrestlers live together as in a large family home. In this one, there are 22 wrestlers; the youngest is just 16, the oldest 36. Years ago, it would have been superfluous to specify their nationality, but not anymore. In fact, more and more foreigners have been successfully breaching the Japanese monopoly in this sport. From 2002 to 2016, Mongolian wrestlers in the top division won 81 out of 88 championships despite a rule that only allows one foreigner per heya.

Fewer and fewer Japanese are joining sumo schools. The typical recruit was usually a young man from a disadvantaged family in a rural area. But in recent years the trend is for young people to move as soon as possible to the big cities for study or for work, certainly not to enlist in the most anachronistic of all “armies” with the strictest discipline and absolute obedience to their superiors’ rules.

It is by no coincidence that now, in front of us spectators, one of the younger recruits gets beaten on the backside by one of the older fighters because, they tell me, he was late last night (apparently he had one too many drinks with some friends). He broke a team rule that says everyone has to go to bed at the same time. A few years ago, a 17-year-old fighter lost his life in training as the result of being heavily punished.

In football, there is a old saying that it’s not a sport for delicate girls. In time it became politically incorrect, but everyone knows the truth at the core of it. In sumo, it is not even enough to be a strong man — you have to be almost superhuman, not only in physical strength but also in nature and mentality. If you want to compete at the highest levels, you really need exceptional drive.

And sometimes that drive has less to do with the hunger for victory than with real hunger. A lot of the young foreigners who enlist in these schools come from humble families who can spare many kids.

Just like the football players who move from Latin America to Europe dreaming of the Champions League, so these boys want to conquer the highest ranks in sumo. Being successful not only translates to the self-fulfilment of a goal, it also means being able to take care of their families in their country of origin. A yokozuna — top division fighter — can even earn US$2 million a year.

In short, young foreigners come to Japan to fight their own private war of social redemption, parallel to that in the stadiums in front of a paying public.

As they began practice, all the fighters start doing something unusual, at least in the eyes of someone who thinks he’s assisting at a sport performance.

They all turn their gaze to the altar and sip sake in honour of the divinity. And what’s more is that perhaps this is the most important part of the whole preparation of the sumo wrestler (rikishi in Japanese): that is the enactment of thanksgiving to the god who in this case is symbolically represented by three twigs of sakaki (the sacred tree) placed high above a wall that demarcates the dohyo, the arena of combat.

We few spectators sit silently behind them on comfortable zabuton, the traditional square meditation cushion.

The sumo wrestlers now all execute that typical gesture that seems to announce the coming battle — the raising of the knees in the air from a sitting position, with legs apart, and then slamming the feet on the floor violently. This ritual, called shiko, was formerly intended to keep evil spirits at bay.

Another common practice for the rikishi is to throw several handfuls of salt into the ring to purify it. Sumo is intrinsically linked to Japan’s native religion, Shinto, or “the way of the gods.”

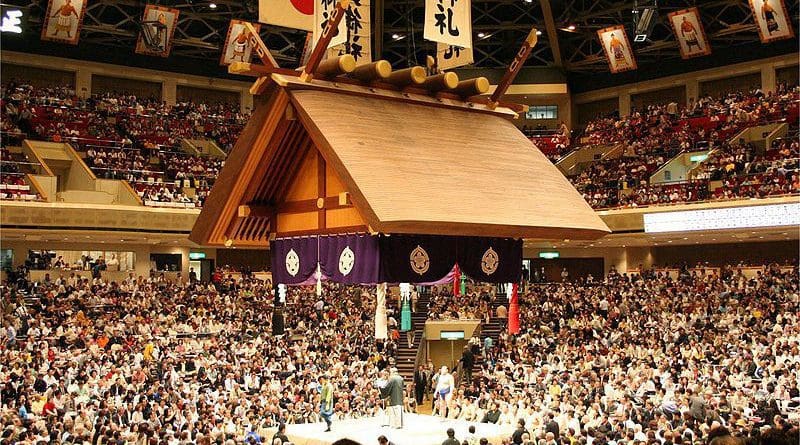

Sumo was in fact originally conceived as a ritual to entertain the kami (gods) during the matsuri (festivals). The same robe worn by the referee resembles the traditional one worn by a Shinto priest.

It’s not hard to tell that sumo is a sport that carries an ancient tradition on its back: the wrestler’s long hair ends with a topknot (chonmage). This hairstyle was once the norm, so much so that anyone who has ever watched a Japanese movie set in the 16th century will soon recognize it. In short, it is a way to honor tradition.

A tradition that, contrary to modern sports, when it comes to formalizing the quality of an athlete will also assess the presence of strong moral values.

In fact, to reach the highest, and almost sacred, ranking of yokozuna, it is not enough to win fight after fight, it is also necessary to demonstrate the right moral attributes, which will be evaluated by a special committee.

And so the fighter who arrived here as a teenager from a remote area of Inner Mongolia is not only training his muscles, he’s going through a genuine conversion of its own spirit, and if victorious he will be blessed with all the honors akin to a semi-god.