Relegating The ‘Russia Problem’ To Turkey – Analysis

Turkey is poking at Russia’s underbelly to the north and north-east where it seeks to undermine Russia’s position through occasional projections of military and economic power.

Turkey’s foreign policy is at a crossroads. Its Eurasianist twist is gaining momentum and looking east is becoming a new norm. Expanding its reach into Central Asia, in the hope of forming an alliance of sorts with the Turkic-speaking countries — Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkmenistan — is beginning to look more realistic. In the north, the north-east, in Ukraine, Georgia, and Azerbaijan, there is an identifiable geopolitical arc where Turkey is increasingly able to puncture Russia’s underbelly.

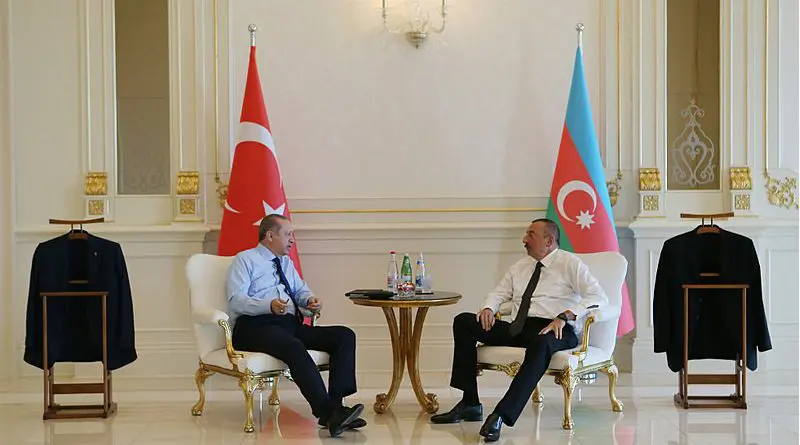

Take Azerbaijan’s victory in Second Karabakh War. It is rarely noticed that the military triumph has also transformed the country into a springboard for Turkey’s energy, cultural and geopolitical interests in the Caspian Sea region of Central Asia. Just two months after the November ceasefire in Nagorno-Karabakh, Turkey signed a new trade deal with Azerbaijan. Turkey also sees benefits from January’s Azerbaijan-Turkmenistan agreement which aims to jointly develop the Dostluk (Friendship) gas field under the Caspian Sea, and it recently hosted a trilateral meeting with the Azerbaijani and Turkmen foreign ministers. The progress around Dostlug removes a significant roadblock on the implementation of the much-touted Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP) which would allow gas to flow through the South Caucasus to Europe. Neither Russia nor Iran welcome this — both oppose Turkey’s ambitions of becoming an energy hub and finding new sources of energy.

Official visits followed. On March 6-9, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu visited Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Kyrgyzstan. Defense cooperation, preferential trade deals, and a free trade agreement were discussed in Tashkent. Turkey also resurrected a regional trade agreement during a March 4 virtual meeting of the so-called Economic Cooperation Organization which was formed in 1985 to facilitate trade between Turkey, Iran, and Pakistan. Though it has been largely moribund, the timing of its re-emergence is important as it is designed to be a piece in the new Turkish jigsaw.

Turkey is slowly trying to build an economic and cultural basis for cooperation based on the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency founded in 1991 and the Turkic Council in 2009. Although Turkey’s economic presence in the region remains overshadowed by China and Russia, there is a potential to exploit. Regional dependence on Russia and China is not always welcome and Central Asian states looking for alternatives to re-balance see Turkey as a good candidate. Furthermore, states such as Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan are also cash-strapped, which increases the potential for Turkish involvement.

There is also another dimension to the eastward push. Turkey increasingly views Ukraine, Georgia, and Azerbaijan as parts of an emerging geopolitical area that can help it balance Russia’s growing military presence in the Black Sea and in the South Caucasus. With this in mind, Turkey is stepping up its military cooperation not only with Azerbaijan, but also with Georgia and Ukraine. The recent visit of Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy to Turkey highlighted the defense and economic spheres. This builds upon ongoing work of joint drone production, increasing arms trade, and naval cooperation between the two Black Sea states.

The trilateral Azerbaijan-Georgia-Turkey partnership works in support of Georgia’s push to join NATO. Joint military drills are also taking place involving scenarios of repelling enemy attacks targeting the regional infrastructure.

Even though Turkey and Russia have shown that they are able to cooperate in different theaters, notably in Syria, they nonetheless remain geopolitical competitors with diverging visions. There is an emerging two-pronged strategy Turkey is now pursuing to address what President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan sees as a geopolitical imbalance. Cooperate with Vladimir Putin where possible, but cooperate with regional powers hostile to Russia where necessary.

There is one final theme for Turkey to exploit. The West knows its limits. The Caspian Sea is too far, while an over-close relationship with Ukraine and Georgia seems too risky. This creates a potential for cooperation between Turkey and the collective West. Delegating the “Russia problem” to Turkey could be beneficial, though it cannot change the balance of power overnight and there will be setbacks down the road.

This article was published by CEPA