Forest Plants Now Flower A Week Earlier Than A Century Ago

Early-flowering plants in European forests today start their flowering season on average a week earlier than they did a hundred years ago. This is reflected by herbarium specimens, as Dr. Franziska Willems and Professor Oliver Bossdorf from the Institute of Evolution and Ecology at the University of Tübingen, together with Professor J. F. Scheepens from Goethe University Frankfurt, have discovered. The research team used the collection dates from herbarium specimens from more than a century for a novel method of geospatial modeling. This also allowed the team to prove that the earlier flowering of wild plants is linked to climate warming. The study has now been published in the journal New Phytologist.

Wood anemones, woodruff, lungwort and spring wood pea bloom early in the year in the forest understory. “They use a critical window of opportunity to flower before the leaves of deciduous trees are sprouting and shading the understory,” explains Franziska Willems. With rising temperatures, leaf buds tend to open earlier, and early bloomers have had to adapt to that as well, she says. “However, they run the risk that their flowers will be damaged by late frost. They also can’t do without pollinating insects, which must be active at flowering time.”

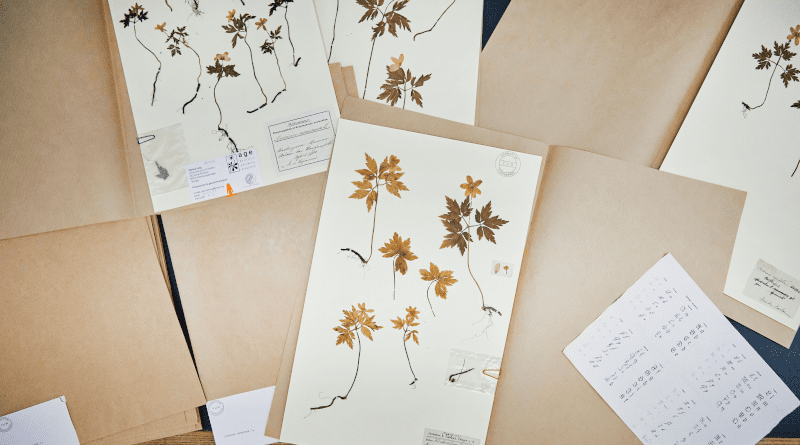

Witnesses from previous centuries

Herbaria – collections of pressed and dried plants – cover large regions and in particular long periods of time. “Many go back 200 years, and hundreds of millions of specimens are stored worldwide,” says Oliver Bossdorf. “Plants are usually collected when they are in bloom, and the collection date and location are noted on the herbarium sheets. This provides a precise snapshot,” says Bossdorf.

For the study, the research team examined more than 6,000 herbarium specimens of 20 early-flowering species collected across Europe to map shifts in phenology, or seasonal developmental rhythms, from these data. To better understand the importance of geographic distribution in the study of phenology, the team created models of flowering times that included geographical information and compared them to models without such spatial data. The results were clear: “The annual rhythms of early-bloomers, and their magnitudes of shifts in response to climate change, vary not only among different plant species, but also across different regions,” Willems says. “For a robust study of phenology changes associated with climate change, you need a large-scale and long-term perspective.” Until now, she says, such studies have often been geographically limited.

The study showed that, on average, plants such as dewberry, wild garlic, and wood sorrel bloomed more than six days earlier now than at the beginning of the last century. These changes correlated closely with warmer spring temperatures. “Flowering time shifted forward by 3.6 days per degree Celsius of warming,” Bossdorf says. Spatial modeling showed that plants bloomed earlier than expected in some parts of Europe, but later in others. “With small-scale studies, the result would have remained unclear. The relationship between the forward shift in flowering time and rising temperatures only emerges clearly in the big picture.”