Principled Pragmatism: Europe’s Place In A Multipolar Middle East – Analysis

By ECFR

By Julien Barnes-Dacey and Hugh Lovatt*

Introduction

A new Middle East is emerging against the backdrop of the United States’ decision to “right-size” its military and diplomatic posture, the increasing assertiveness of regional states, and greater Russian and Chinese engagement in Middle Eastern affairs. These geopolitical shifts are eroding Washington’s long-standing ascendancy in the Middle East and creating a new multipolar order. They are being accelerated by Russia’s war on Ukraine and intensifying global competition between great powers. Long accustomed to moving in the United States’ slipstream, Europe now confronts an increasingly challenging and competitive southern neighbourhood.

The war in Ukraine has heightened competition for influence in the region between European states and their key strategic rivals, Russia and China. Russia’s invasion has also sent shockwaves through global energy and food markets, which could deepen humanitarian crises at a time when the Middle East is already grappling with widespread economic collapse and, in some cases, state failure. This could have knock-on effects for issues related to migration and terrorism – two challenges that have long dominated European concerns in the region. The war has also underscored the Middle East’s growing importance as a source of energy, as European states scramble to reduce their dependency on Russian oil and gas.

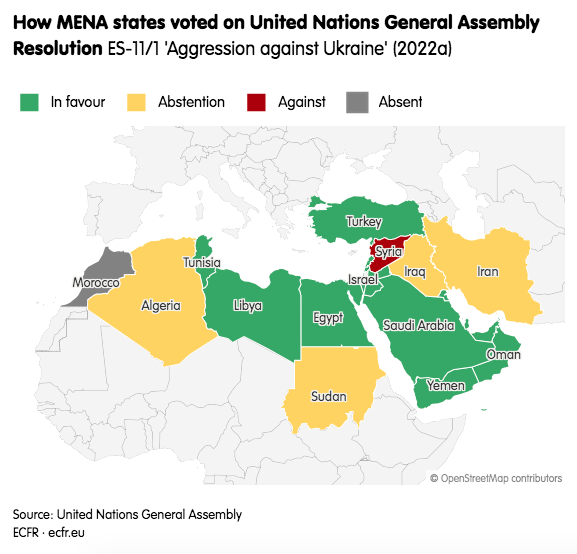

As Europe becomes ever more intertwined with the Middle East, its vulnerabilities will grow. Middle Eastern and North African states find themselves in a strong position, with new sources of leverage to use against European capitals as they hedge between global powers. The reluctance of Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates to align with the West on Ukraine – as well as Beijing’s accelerated efforts to pay for Middle Eastern oil in yuan rather than US dollars – only add to the complexity of the geopolitical landscape. Added to this is the possibility that Russia will use its presence in countries such as Libya and Syria to retaliate against European states for supporting Ukraine. The possible collapse of the Iranian nuclear negotiations could reinforce these dynamics.

The Middle East’s geopolitical transformation has huge implications for Europe, but the EU and European states are still widely regarded as inconsequential actors in the region. The bloc’s long-standing reliance on the US and predictable weaknesses – disunity and an inability to engage in the cut and thrust of competition between great powers – have too often left it unable to shape developments.

This needs to change. As Europeans seek to present themselves as more willing and able players in the competitive global order, they need to address the ways in which the Middle East also affects core political, economic, and security interests.

The development of a multipolar regional order highlights the need for Europeans to become more influential regional actors and, counterintuitively, an opportunity for them to do so. This new landscape, in which no single power is dominant, could provide space for groupings of like-minded European states, including Norway and the United Kingdom, to promote European interests more effectively. Much will depend on whether Europeans can avoid narrow transactionalism – driven particularly by new energy needs – by forging more strategic and collective positions on key issues. European states’ response to the war in Ukraine shows that they can adopt a coherent and assertive foreign policy when required. They need to replicate this effort in their southern neighbourhood.

Europeans already bring a lot to the table in terms of economic, financial, and political engagement – something that is often underappreciated. But, if Europeans want to shape the geopolitical dynamics of the Middle East, they need to be more clear-sighted about what is achievable. This will require Europe to show principled pragmatism in acknowledging the region as it is – rather than as they want it to be – in pursuit of their core interests. They need to do so in a manner that avoids ceding leverage to regional actors, and that still aligns with their overriding principles – by focusing on support for the bottom-up, incremental reform needed to create long-term stability. This approach should involve more effectively tapping into the opportunities presented by stabilisation support, green energy, and regional economic diversification, while also reconfiguring the transatlantic relationship to maximise the effectiveness of Western policy based on an acknowledgement of Europe’s and the United States’ shifting priorities.

Importantly, Europeans should push back against attempts to view regional engagement through the narrow lens of great power competition. This approach would reduce the risk of further polarisation in the Middle East and would align with Europe’s interest in stabilising the region. To be sure, Europeans need to counter growing Russian and Chinese influence in their southern neighbourhood. But they still need to maintain space for some coordination with Russia and China on important shared interests relating to energy security and stabilisation imperatives.

In recent years, destructive proxy conflicts in states such as Libya and Syria have demonstrated the degree to which the Middle East’s changing geopolitics can fuel instability. As Middle Eastern states adapt to the new regional order, hesitantly moving from war to diplomacy, Europe should use this emerging multipolarity to support regionally-owned diplomatic efforts to de-escalate conflicts and help stabilise the region.

US retrenchment

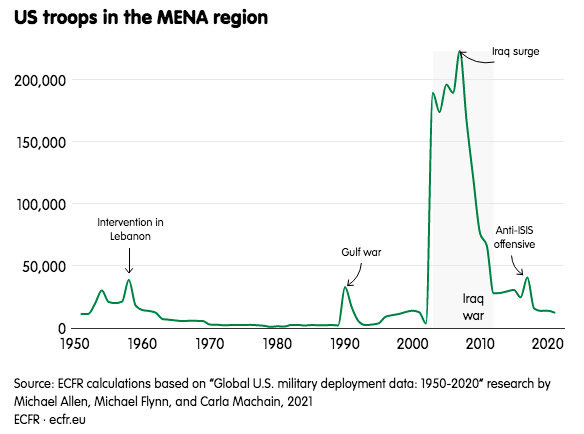

In recent decades, Europe has grown comfortable in a Middle East dominated by the US. The end of the cold war and the defeat of the Iraqi forces that invaded Kuwait in 1991 consolidated the United States’ position as the regional hegemon. At its core, the US regional order rested on the flow of Gulf oil and the provision of security guarantees to key allies such as Israel and Saudi Arabia. At one point in the 2000s, at the height of the Iraq war, more than 200,000 US troops were deployed in the region.[1]

Until 2003, US ascendancy was largely uncontested. This modus vivendi between the US and regional actors frayed following its invasion of Iraq that year, which opened the door for Iran to widen its influence. But, even then, most key actors in the region and beyond continued to view the US as the primary guarantor of the Middle Eastern security order.

With Washington doing most of the heavy lifting politically and on security matters, this US-led Middle East asked little of Europe. Shielded from geopolitical competition, the EU sought to transform its southern neighbourhood through ambitious trade agreements and development support – although several European states did actively support the US-led war in Iraq in 2003.

However, in response to the turmoil that followed the 2011 Arab uprisings, Europe quickly shifted towards a focus on preventing migrants from reaching its shores and on countering terrorism threats emanating from the region. This occasionally led European countries to deploy security and training missions from Libya to the Gulf. These missions have tended to revolve around France and the UK, which maintain military bases throughout the region. London and Paris came together, for instance, to help topple Libya’s long-time leader, Muammar Gaddafi, and to fight the Islamic State group (ISIS) in Iraq and Syria.

More often than not, though, when Europe has acted militarily, it has done so under the umbrella of US leadership. In Libya, the US famously “led from behind”. Europeans remain wholly dependent on Washington in the fight against ISIS and would have curtailed these efforts if then-president Donald Trump had followed through on his 2018 threat to end US military activities in Syria. Paris has long complained about former president Barack Obama’s unwillingness to punish Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad for using chemical weapons in 2013, but neither it nor London chose to step in without cover from Washington.

On the political front, there have been signs of greater European initiative. The E3 states – France, Germany, and the UK – and the European External Action Service went to great lengths to try to salvage the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) following the US withdrawal from the agreement in 2018. France has also taken the lead in regional de-escalation efforts, while Sweden and Germany have played a notable role in trying to support peace efforts in Yemen and Libya respectively.

Nonetheless, these European diplomatic tracks have faltered. And Europe’s wider engagement with the region since 2011 has also failed to bring about positive political transformations or create stability. The most striking examples of this are failed efforts to bring about a post-conflict political transition in Libya, a task that Obama largely delegated to European leaders. Meanwhile, the democratic transition in Tunisia – a country in which Europe has been far more invested than the US – is running aground. In Lebanon, too, European efforts to avert state collapse have come to nought.

A parting of ways

US leadership has long provided European states with an excuse to avoid confronting their own lack of initiative, political will, and coherent policies. But Trump upended this arrangement – and with it Europe’s position in the region. Europeans found themselves cast aside and at odds with their American counterparts on key issues, no longer able to look to the US to protect their core regional interests.

Trump demonstrated an unprecedented desire to withdraw the US from costly military commitments across the Middle East. The critical demonstration of this shift was Washington’s unwillingness to respond to the September 2019 drone and missile attacks on Saudi Aramco oil facilities in Abqaiq. The attacks, which temporarily cut Saudi Arabia’s oil production by around half, were widely blamed on Yemen’s Houthis and Iran. The lack of a reaction from the US, despite its long-standing commitments to Saudi Arabia’s security and regional energy supplies, sent a shudder through Gulf Arab states. Seen from regional capitals, this non-response was a firm sign of the United States’ abandonment of its role as their security guarantor.

Europe’s inability to effectively wield influence in Washington to maintain the US commitment to the JCPOA was the biggest manifestation of this breach in transatlantic cooperation. Another notable division emerged over Trump’s unconditional support for Israel’s annexation of Palestinian territory and dismissal of a future two-state solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Many European officials breathed a deep sigh of relief when Trump left office, hoping that things would go back to the status quo ante.[2] But it would be a profound mistake to view US policy on the Middle East during those years as an anomaly. Washington’s declining interest in the region and its marginalisation of European interests there reflects a structural shift that has been under way since the Obama administration took office, in 2009. Barring an event such as a direct confrontation with Iran, this general trend will continue unabated under President Joe Biden – and could accelerate further if Trump or a similarly minded Republican wins the 2024 US presidential election.

Right-sizing

After two decades of intense military engagement with the Middle East – marked by the deployment of hundreds of thousands of US troops and the deaths of thousands of these soldiers – the US is recalibrating. This is partly driven by domestic fatigue with inconclusive military interventions and a desire to end “forever wars”. But it also reflects shifting strategic calculations.

The US is no longer dependent on Middle Eastern energy supplies, long a prime reason for its regional posture. Gulf energy flows remain important to global markets and will continue to have a direct impact on the American economy. But, in 2019, the US became a net energy exporter for the first time since 1952. More importantly, having set its strategic gaze on China, the US wants to redirect its political focus and resources away from the Middle East – an arena it sees as costly and unrewarding – and towards the Asia-Pacific.

Biden has sought to concretise this strategic shift, sending out a series of signals to reinforce this message. These signals include the formation of a smaller Middle East and North Africa directorate within the US National Security Council, the slow-rolling of post-inauguration phone calls with regional leaders, and a clear de-prioritisation of totemic issues such as Syria and the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. Biden only nominated a new US ambassador to Saudi Arabia in April 2022, more than 15 months after his inauguration.

Given the profound shift in US strategic thinking – emphasising great power competition and the need to counter China’s rise – the US will not reverse its de-prioritisation of the Middle East. While the US may momentarily increase its diplomatic engagement in the region to manage the fallout of the Ukraine war, this is likely to be a stopgap response to secure necessary energy supplies rather than a strategic refocusing. Ultimately, the desire to confront Russia more directly will underscore Washington’s need to reorder its global priorities, likely increasing its desire to reduce its Middle Eastern commitments.

To be clear, this does not signal an end to the United States’ regional presence: its troop reductions are, in fact, merely a return to the number of soldiers it deployed in the region in the 1990s – hence Washington’s description of its actions as right-sizing rather than withdrawing. With more than 13,000 US troops still in the region (and the capacity to quickly increase these numbers), as well as large military bases in the Gulf, this presence still dwarfs the 4,000 troops that Russia deployed to Syria in 2015.

The major change is in the United States’ decreasing political willingness to be involved in the region’s myriad problems. A deliberate desire to do less in the Middle East will entail a recalibration of US ambitions, eschewing a broad-based – and, at times, nebulous – agenda in favour of a more clearly defined set of objectives.

When the US acts in the region in future, it will likely be in narrow areas of direct importance to its national security.[3] Its foremost priority will remain counter-terrorism. Alongside this, the US will continue to prioritise political and military support for Israel. A related priority will be to keep Iran in check, especially in relation to its nuclear programme. The Gulf will remain a key focus given the importance of protecting freedom of navigation and international commerce transiting through the region, as well as its influence on global energy prices – as has been illustrated by the fallout from the war in Ukraine. In a global economy characterised by soaring energy prices, Gulf Arab states – which also have unique capital liquidity with which to fund regional allies and pursue their foreign policy objectives – will regain some importance in the coming years.

While the US and Europe will continue to share broad interests, their priorities and focus will increasingly differ. This is especially true in North Africa and the Levant, and on wider stabilisation imperatives – which the US increasingly sees as less critical to its security than Europe does.

A new multipolar regional order

This US recalibration is not happening in isolation. It has created a perception of US disengagement that is significantly shifting the calculations of regional and non-regional states. As they increasingly jostle one another to secure their interests, Europe faces the prospect of an ever more complex multipolar order in its southern neighbourhood. It will have to compete against an array of actors who have proven to be far more geopolitically adept and assertive, and who are already seeking to brush Europeans aside in countries such as Syria and Libya.

The challenge from Russia and China

Much of the attention of Western policy experts has focused on the rising political, economic, and military presence of Russia and China. The two countries are pursuing their own agendas characterised by differing priorities and interests. It would be a mistake to view them as a united bloc in the region (although there is some overlap within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation’s activities). But Russia and China both appear to see an opportunity to consolidate their influence and challenge Western sway.

In recent years, Moscow has skilfully inserted itself into key conflicts to build up its wider influence. Since its military intervention in Syria in 2015, Russia has deployed forces to Libya (through unofficial fronts such as the Wagner Group); built up its security relationships with key states, particularly Gulf monarchies and Egypt; and positioned itself as a key regional interlocutor with Israel and Iran. Throughout this process, Russia has protected the interlinked interests of states such as Israel even when they come into conflict with its partnerships with Syria and Iran. This has resulted in Israel coordinating with Russia when striking Syrian- and Iranian-affiliated targets in Syria, even as Moscow continues to work closely with Tehran to consolidate the Syrian regime’s position on the ground.

In doing so, Moscow has opportunistically presented itself as a dependable security provider that is willing to support authoritarian regimes without interfering in their internal affairs (while also providing important support in the UN Security Council). These relationships have been bolstered by a convergence between Russia and regional oil producers in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries Plus. Since 2017, they have aligned on oil production quotas to prop up oil prices, including in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

China, meanwhile, has been more cautious. But it is also building up its regional role, as reflected in a significant increase in its political and economic activity. China’s global strength is such that many view its growing influence as far more of a strategic transformation of the regional landscape than that instigated by Moscow.

With a potential confrontation with the US over Taiwan in mind, China may view deepening relations with the Gulf as a means of protecting its economic and energy security from the potential impact of Western sanctions – which could resemble those imposed on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine. Beijing is now pressing for Saudi oil sales to China to be priced in yuan rather than dollars – a signal of its desire to challenge US financial dominance in the oil market and de-dollarise the global economy.

Unlike Russia, China’s regional influence is being built on an economic rather than security platform. China’s rapidly growing economy makes it the world’s largest importer of oil – 47 per cent of which came from Middle Eastern countries in 2020. Driven by its search for export markets and immense demand for energy, Beijing has assiduously strengthened its economic relations with Gulf Arab states and Iran.

In the Middle East, as in other parts of the world, the primary vehicle for China’s economic interests has been its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which promotes infrastructure and connectivity projects. Much of this is spin, with Chinese investment data incredibly opaque and stated commitments often failing to materialise. But part of China’s current allure in the region comes from its image as a source of significant economic benefits for its partners.

In 2020 China reportedly replaced the EU as the largest trading partner of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), with bilateral trade valued at $161.4 billion. According to data compiled by Shanghai’s Fudan University, the BRI is a major source of Chinese foreign direct investment in the Middle East, which allegedly rose by around 360 per cent between 2020 and 2021. China is also reportedly increasing its economic sway in Iraq, which Chinese figures suggest received more than $14 billion in Chinese investment in 2021. These figures are overstated but, nonetheless, help create a perception in the region that Beijing is bringing it under the Chinese economic umbrella. Key to China’s appeal is its willingness to dispense with Western-style preconditions such as support for human rights and democracy, as well as a relatively large appetite for investment risk.

Beijing is increasingly looking to translate its economic weight into political influence. Today, it has strategic partnership agreements with five Middle Eastern and North African countries (Algeria, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Iran). Riyadh may be Chinese President Xi Jinping’s first foreign travel destination since the covid-19 outbreak. And, like Russia, China has waged an intense campaign of vaccine diplomacy to demonstrate its value to its regional partners.

Although China has concentrated its regional efforts on energy supplies and economic contracts, it is slowly beginning to assume a security role. This was initially motivated by its desire to protect its citizens and business interests in the region – including in Yemen, where a Chinese naval frigate evacuated Chinese and foreign nationals during the escalating war in 2015. Alongside this, its navy has conducted anti-piracy missions off the Horn of Africa.

This security role is facilitated by China’s expanding infrastructure projects, notably through investment in ports in the Mediterranean and the Gulf. For the moment, China’s security role in the region remains limited – but recent developments point to a shifting calculus in Beijing. Foremost among these developments are China’s reported plans to build a secret naval base in the UAE, as well as its support for Saudi Arabia’s ballistic missile programme.

While China has long been content to work under a US security umbrella, prompting Obama’s accusations that it was a “free rider”, Beijing may now believe that the perceived downgrade of US security guarantees creates not just a need to do more to protect its energy and trade interests but also an opportunity to expand its influence. Beijing may also see an enhanced role in the Middle East as a potential counter to Washington’s pivot to Asia – although it does not yet appear to have decided whether it should adopt a policy of systemic confrontation with the US in the region.[4]

China’s and Russia’s new inroads into the Middle East form part of a resurgence of competition between great powers. This contest is shaped by factors such as Russia’s war on Ukraine and growing tensions between the US and China on issues such as the future of Taiwan, human rights abuses in Xinjiang, and global trade. As a result, some US policymakers are pushing for Washington to confront China and Russia more directly in the Middle East. For instance, members of Congress have called on the US government to develop “a strategy for countering and limiting the People’s Republic of China’s influence in, and access to, the Middle East and North Africa”.

This backlash against growing Chinese influence is already occurring in the military and technological realms, with the US redoubling its efforts to shut China’s military out of the Gulf, and to exclude its technology exports to, and investments in, Israel and Gulf Arab countries. US opposition to the UAE strengthening its ties with China led to the collapse of a multi-billion-dollar deal for the Emiratis to buy F-35 fighter jets. Washington feared that the agreement could have caused advanced military technology to fall into Chinese hands.

Nevertheless, while both Moscow and Beijing are expanding their regional ambitions and looking to rival the West, there are limits to their current influence and capabilities.

There are real questions surrounding Moscow’s staying power, given the largely opportunistic nature of its interventions and the costs of its invasion of Ukraine. Middle Eastern governments (particularly dictatorships) have been happy to develop their relationships with Moscow thanks to the short-term gains of these ties. But key regional actors such as Gulf Arab states are unlikely to see Russia as a long-term strategic partner, particularly following its invasion of Ukraine. The increase in Chinese regional influence has been steady but remains in its early stages, with China’s political and security commitments – like Russia’s – still dwarfed by those of the US. Some Chinese experts point to what they see as Beijing’s current lack of an overarching strategy for the Middle East.[5]

Despite trumpeting its contributions, Beijing has shown a tendency to over-promise and under-deliver. Contracts with Beijing are often onerous, including in their requirements to use Chinese workers and terms that result in capital extraction in Beijing’s favour. As one official based in a Gulf Arab state noted: “whenever I get something from China, I read the fine print three times.”[6] Moreover, since 2006, China has been involved in more than $42 billion of “troubled transactions” in the Middle East, based on research by the American Enterprise Institute. This term describes commercial agreements that were impaired somehow or that failed outright; it omits the extensive financial pledges that have yet to materialise – such as the $400 billion of investment promised to Iran.

In recent decades, the US has learnt the hard way that it is no easy task to manage Middle Eastern allies and opponents. Unsurprisingly, neither Beijing nor Moscow appears keen to inherit these headaches. Even though Moscow and Beijing share a deep conviction that Western interventions in the Middle East have only created instability,[7] both have long benefited from the US-maintained security order – and, fundamentally, have not sought to replace it. Nor have they shown any desire to invest serious political capital in addressing the region’s toughest challenges, such as the conflicts in Israel-Palestine, Libya, and Yemen. Beijing appears particularly keen to avoid unnecessary entanglements in turbulent regional politics.

A more assertive region

An equally critical aspect of the region’s new multipolarity is the rise of more independent-minded regional actors. Their response to increasing global competition has been to hedge between international powers as a way to safeguard their interests. This has been most clearly demonstrated by the reluctance of the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Israel to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Gulf Arab states, Israel, Iran, and Turkey are now positioning themselves as gatekeepers to the interventions of external powers, which they are trying to leverage to their advantage.

Middle Eastern countries, particularly the United States’ long-standing regional partners, are using great power dynamics to underscore their anger at Washington’s perceived neglect of their security concerns. Saudi Arabia, one of the United States’ oldest allies in the region, exemplifies this dynamic: Riyadh has rejected Western requests to condemn Russia for the invasion of Ukraine and to increase oil output to offset the decrease in Russian energy supplies – preferring ongoing cooperation with Moscow to maintain high oil prices. A more brazen signal was sent by the Saudi Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman and Emirati Crown Prince Muhammad bin Zayed: during the first few weeks of Russia’s war on Ukraine, they reportedly refused to speak to Biden but had conversations with President Vladimir Putin.

More widely, Egypt has in recent years threatened to develop a deeper security relationship with Russia in response to growing US pressure over its deteriorating human rights record. Meanwhile, President Kais Saied has been pushing back against perceived European interference – including in response to his seizure of power – with Tunis also playing up opportunities with Russia.

The United States’ long-standing regional partners see the current moment as an opportunity to make clear that the US should change tack if it wants to prevent them from strengthening their ties with Russia and China. Reports suggest that Saudi and Emirati willingness to support the US with increased oil output is conditioned on greater American efforts to counter the Houthis – which Washington is resisting, due to its desire for a political solution to the conflict in Yemen. The Saudi crown prince also reportedly wants US recognition as the heir apparent to the Saudi throne, including to secure legal immunity in the US, given the allegations that he was involved in the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

Nevertheless, despite the growing acrimony, this positioning should not – for the moment, at least – be read as a sign of a strategic pivot towards Russia or China. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are aiming to reduce their singular reliance on the US. And they see Russia and China as potential alternative partners. This goes some way to explaining the UAE’s intention to purchase Chinese L15 fighter jets. But the deeper reality is that neither Russia nor China can currently provide what the US has to offer – particularly in the military realm, where it remains the dominant security guarantor and largest exporter of arms to the region. Middle Eastern states know this. In fact, they are primarily focused on leveraging great power dynamics to force the US to recommit to the region. When faced with Houthi missile attacks on their territory, Saudi Arabia and the UAE still turn to the US – and not China or Russia – for support. Washington has transferred a significant number of Patriot air defence systems to Saudi Arabia in recent months in response to requests from Riyadh.

But Gulf Arab states may be playing a dangerous game. Their positioning over the Ukraine crisis is generating increasing anger among Western politicians, who point to the fact that the West has provided security support to Riyadh and Abu Dhabi for decades. The West’s short-term imperative of securing new energy supplies strengthens Gulf states’ current position. But they risk overplaying their hand in a fashion that could widen the gap between the sides in the long term.

Perceived US retrenchment has pushed Middle Eastern states to not only play great powers off against each other but also to become increasingly assertive abroad. These dynamics have deepened geopolitical fault lines across the Middle East. Most significantly, Iran and its network of state and non-state actors have pitted themselves against a counter-front of traditional Western allies centred on Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Israel. This contest has had brutal consequences in Syria and Yemen. It was also a key motivation for the normalisation of relations between Israel and the UAE as part of the Abraham Accords. Their overlapping strategic calculations in favour of the agreement include a recognition of the growing need to diversify away from reliance on the US.

The regional security order has also come under strain from competition between self-defined anti-Islamist states, particularly the UAE and Egypt, and those such as Turkey and Qatar that support the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist organisations. This confrontation led to the blockade on Qatar by other members of the GCC, and fuelled Libya’s on-off civil war. The conflict in Libya is a prime example of how, in a multipolar order, such contests tend to suck in other external players (including Russia). This is also now occurring in Tunisia, where Egypt and some Gulf Arab states are encouraging Saied’s attack on the one surviving democratic success to come out of the 2011 Arab uprisings.

Middle Eastern states’ growing assertiveness has involved the development of indigenous military capabilities. Turkey and Israel now export their weapons, particularly drones, globally. Alongside the UAE, which has also positioned itself as a conduit for the flow of arms across the region, these countries are shaping battlefield dynamics as far afield as Ethiopia, Azerbaijan, and Ukraine. Turkey and the UAE have both established bases in Libya and the Horn of Africa.

Still, the burden of managing their own security, coupled with immense fatigue after a decade of conflict, appears to now be pushing regional states towards diplomatic compromise. With Gulf Arab states no longer feeling able to count on the US to protect their interests vis-à-vis Iran – a belief cemented by Washington’s efforts to restore the nuclear agreement with Tehran – they have pivoted to engagement, hoping to prevent dangerous escalation. The August 2021 Baghdad Conference was a notable breakthrough, drawing key regional actors into dialogue with one another. It has been accompanied by bilateral talks, particularly those between Riyadh and Tehran. Muhammad bin Salman last year called for “good and positive relationship” with Iran, while Abu Dhabi recently expressed a need for a “functional” relationship with Tehran. Meanwhile, the internal GCC rift ended in January 2021. And Turkey is now restoring its ties with the UAE and Saudi Arabia, as well as Israel.

However, this shift to diplomatic de-escalation remains vulnerable to disruption, as it is largely based on a tactical need to prevent instability rather than a strategic embrace of re-engagement. It also risks being fatally undermined by the possible collapse of the Iranian nuclear talks, which could quickly deepen regional fault lines and push various actors towards a new conflict.

Multipolar realities

While the US can justify partial disengagement from the Middle East, Europe’s geographical position means that it will always be vulnerable to instability in the region. The challenges posed by migration and terrorism will continue to concern European voters and politicians. The destabilising impact of rising food prices on already vulnerable states as a result of the Ukraine war could exacerbate these problems. Energy security is also emerging as a fundamental regional interest for Europe, due to its desire to reduce its dependence on Russia. In areas such as trade and climate, Europe and the Middle East have shared interests that will grow in importance in the coming years.

Middle Eastern countries have been relatively quick to come to terms with the consequences of US right-sizing. European states need to catch up by developing a regional strategy that protects their interests and accounts for these consequences. Europe will need to become more assertive itself, moving beyond its traditional deference to US leadership and ensuring that it is no longer a mere supplicant in search of help on energy, migration, and terrorism issues.

Europeans need to assess how the shifting geopolitical landscape can play to their advantage. At its core, the EU should capitalise on the fact that multipolarity can create more space for it to operate in – or, at the very least, allow coalitions of its member states to exert greater influence and compete more effectively with other actors. While Russia and China often exert outsized influence in the Middle East, Europe has long failed to wield as much power as it could. Europeans need to work out how to reverse this trend, by deploying their political, economic, and security capabilities to greater effect.

Moreover, Europeans should see a multipolar order as a framework that can now support regional stability. In the past decade, the Middle East has been defined by conflict and polarisation, partly fuelled by multipolar competition. But states in the region increasingly acknowledge the need for a more cooperative, diplomatic approach. This needs to be supported and could allow for a greater focus on non-security issues, such as the impact of climate change and the need for economic diversification – both of which will be at the heart of future challenges to stability.

In contrast, heightened competition between great powers will further polarise the region – pushing Middle Eastern governments to either choose sides or play these powers off against one another (as has been demonstrated by the war in Ukraine). Middle Eastern governments are likely to use these dynamics to bolster regime security rather than improve governance in a way that aligns with core European stabilisation interests.

To be sure, multipolarity does not mean giving free rein to Beijing and Moscow. Europe needs to prevent Russia and China from establishing dominant positions that could threaten its interests. Europeans will need to carefully evaluate the extent to which growing Chinese influence in the region is affecting their security, particularly in relation to supply chains and digital infrastructure. In the near term, Moscow could try to exploit Europe’s vulnerabilities in the Middle East to divert its resources and attention away from Ukraine, while simultaneously trying to relieve some of the political and economic pressure it is under from mounting international sanctions. For example, the Kremlin could seek to destabilise Libya and Syria, hoping to force refugees to flee to Europe.

But it would not be in Europeans’ interest to shut down all avenues for coordination with Moscow or Beijing. This could push them towards closer regional alignment – a dynamic that has not yet materialised on the ground despite their cooperation at the UN Security Council and in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. China, in particular, is invested in regional stability due to its need for stable energy flows and freedom of maritime navigation. China and Russia also share some of Europe’s non-proliferation concerns, as demonstrated by their long-standing cooperation with the West to address Iran’s nuclear programme.

Global competition increasingly threatens to undermine this regional cooperation. Moscow’s sudden turn against the JCPOA earlier this year – which it has since reversed, but which came in response to Western sanctions on Russia – shows how great power competition could have severe consequences for Western interests in the Middle East.

Recommendations

Facing US retrenchment from an increasingly multipolar Middle East, Europeans need to find more assertive and effective ways to protect their interests in the region. As others compete for attention and influence, they should demonstrate that the region remains a high priority. If anything, Europeans should be devoting greater political energy to the region. It would be a profound mistake to think that Europe can seal itself off from regional challenges, focusing narrowly on migration and energy transactionalism, as it prioritises the Russian threat to Ukraine.

The forthcoming EU-GCC Joint Action Plan shows a commitment to the Gulf, but Europeans need to tie it more closely to wider dynamics, including those involving Iran. Europeans should use the diplomatic momentum from a possible new nuclear agreement with Tehran to help consolidate de-escalatory talks between Iran and Gulf monarchies. To this end, European leaders need to press Washington and Tehran to take the final steps to reach an agreement – rather than allow a dispute over the symbolic delisting of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps to derail talks. If the negotiations do collapse, Europeans will need to quickly take the lead to sustain a diplomatic track that averts further Iranian nuclear escalation and prevents a dangerous new regional conflict.

Their wider efforts should include a particularly strong focus on Yemen, given its centrality to the rivalry between Iran and Gulf Arab states. The recent ceasefire in Yemen provides an opportunity for an immediate surge in European political and humanitarian engagement with the country.

Europeans should reverse the general policy drift away from the crises in Libya, Tunisia, and Syria. In Libya, for instance, they need to make a determined effort to help the UN special adviser resurrect the country’s political process and prevent it from falling back into conflict.

As they focus on these efforts, Europeans need to acknowledge – and reverse – the degree to which the complex multipolarity has all too often fractured their unity and effectiveness on many of these issues, as highlighted by the deep divisions between them over Libya. This incoherence allows rival powers to divide European states against one another, increasing their own influence at the latter’s expense. If Turkey and Russia are now dominant actors in Libya, it is in no small part because Europeans failed to coalesce behind an effective strategy. A more coherent European approach could have mitigated the instability caused by these overlapping interventions.

Combined action by all 27 EU member states remains unlikely, reflecting a lack of unity that will continue to undermine European efforts. But it is imperative that core groups of the most active players – including the likes of France, Germany, Denmark, Italy, Spain, and Sweden, as well as EU institutions – come together to forge more effective groupings. Engagement with the UK and Norway – influential countries in their own right in the political and stabilisation spheres – would further increase the EU’s clout. The UK’s ability to work with its EU partners in support of Ukraine shows what is possible with the right political will.

Guided by these immediate priorities and the need for greater cooperation with one another, European states should now follow five broad approaches to policy on different regional issues.

1) Embrace principled pragmatism

As Europeans assess how to project influence in a multipolar order, they need to strike a balance between two extremes. Instead of vacillating between transactional dealmaking and illusory political transformation, they should adopt a foreign policy based on principled pragmatism. This would help them adapt their strategy and goals to the cut and thrust of complex regional geopolitics and overcome the belief in Middle Eastern capitals – as well as in Washington, Moscow, and Beijing – that they are not serious actors.[8]

The EU’s predominant focus on migration control and counter-terrorism has increasingly led it to adopt a securitised approach to the region. This approach has privileged the stability of authoritarian powers such as the UAE and Egypt, and has involved deals such as that with Libyan militias to halt migration to Europe. This approach has succeeded in a narrow sense, by reducing irregular migration flows and preventing further terrorist attacks in Europe. But it has done so in a limited and precarious fashion, embracing a transactional approach, which neglects core drivers of instability feeding migration and terrorism such as bad governance, limited economic opportunities, and rampant corruption. Significantly, it has also done so in a fashion that has left Europe as a weak demandeur.

Regional states, including key partners, have repeatedly proved adept at leveraging Europe’s interests and concerns for their own gain. Morocco and Turkey exemplify this dynamic, repeatedly using irregular migration to pressure the EU and its member states into concessions. Europe’s colonial past and habit of preaching democratic values – unlike Russia and China – has further damaged its credibility, provoking accusations of hypocrisy and double standards that are rarely levelled at Beijing or Moscow.

Europe’s prioritisation of short-term objectives over longer-term sustainability is accompanied – in a somewhat chaotic fashion – by a contrasting fondness for grand political fantasies. This tends to manifest in the pursuit of largely illusory long-term aspirations at the expense of more politically difficult, and diplomatically laborious, efforts that might lead to practical progress and forward momentum towards regional stabilisation goals.

The clearest example of this is the EU’s continued emphasis on reviving the defunct Oslo peace process between Israelis and Palestinians. It is also reflected in the union’s belief that rapid elections can resolve all Libya’s problems. In Syria, meanwhile, Europeans remain tied to an outdated vision of political transformation despite Assad’s continued hold on power. This positioning has too often left the bloc unable to meaningfully shape developments, as it is pushed aside by rivals that better respond to the realities of power.

A more coherent approach necessitates a better balance between these two extremes. Europe will, of course, need to be pragmatic in dealing with regional power brokers if it is to protect its interests in areas such as migration control, counter-terrorism, and energy security. This will mean engaging with the likes of Saudi Arabia and Egypt despite concerns over their governance failings. In theatres such as Libya and Syria, Europeans need to pursue policies that can more effectively grapple with realities on the ground. Here, as elsewhere, they need to roll up their sleeves and get involved if they are to shape positive outcomes.

But this needs to be done in a way that avoids weakening their positions vis-à-vis regional actors. Europeans should be willing to reject what often amounts to attempts at blackmail, particularly on the migration and economic fronts (the latter often driven by regional arms sales). Even as Europeans are pragmatic, they should ensure that their engagement is not taken for granted by regional partners. In dealing with major energy producers, for instance, Europeans should more confidently assert the value of their political, economic, and security support. This would create the conditions for more balanced relationships.

Elsewhere, as Tunisia’s democracy struggles to survive, Europeans need to use their close ties with the country to press Saied to loosen his grip on power, while working to prevent a broad economic unravelling. On the Israel-Palestine conflict, they should use their relationships with the sides to incentivise Israeli political and public moves towards de-occupation, and to advance Palestinian political reunification and institutional reform.

This approach should be guided by Europe’s core interest in lasting stability, not least through the establishment of inclusive and accountable governance structures. Europeans’ pragmatism should not be used to entrench negative dynamics, such as poor governance and authoritarianism – as it would if they unquestioningly accepted diktats from their regional partners. Europeans should remain committed to standing up against egregious human rights violations. Again, however, Europeans will need to be cognizant of the limits – and sometimes counterproductive nature – of their entreaties on this issue.

Given the pushback from regional elites against foreign interference in their domestic political affairs, Europeans need to adopt an approach that is humbler and focused on viable outcomes. They should recognise that they will be more successful in promoting stabilisation and transformation by focusing their efforts on support for incremental bottom-up institutional reform rather than swift, government-led change. Europeans should prioritise support for civil society, focusing their efforts on strengthening local actors’ capacity to catalyse positive change in line with their political goals. This means a greater focus on less overtly political initiatives. In Lebanon, for example, rather than fixating on a high-level political settlement, Europeans should increasingly invest in local partners and institutions that can prevent the total collapse of the state, and should support grassroots reform in key areas such as anticorruption and public services.

2) Leverage European assistance

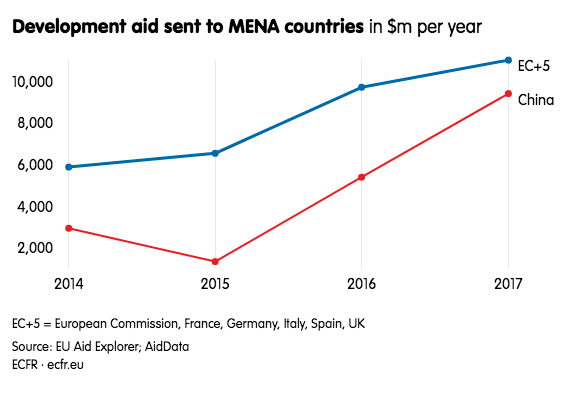

This principled pragmatism, which combines the pursuit of urgent goals with a strategy to create stability in the longer term, will require Europeans to make better use of the unique economic and financial tools at their disposal. In light of Middle Eastern governments’ desire for more foreign support, Europe has a significant opportunity to demonstrate that it is a more strategically valuable partner than Russia – particularly a Russia under strict Western sanctions – and that it can compete with China in the provision of economic benefits.

The EU and its member states have already contributed much to the region, channelling $33 billion in aid and $1.2 trillion in foreign direct investment to it between 2014 and 2017 alone.[9] While publicly available data on Chinese aid and investment figures is incomplete, there is a good chance that Europe will make a greater contribution than Beijing. Europeans need to transform this economic weight into strategic influence.

Given that the region now faces critical – at times, existential – challenges related to economic diversification, growing populations, climate change, and the energy transition, Europe’s unique position in these areas should give it an additional edge over Russia and China. While Beijing may lead the way in producing solar panels, for instance, Europeans’ technical know-how on green energy is more advanced. Across the Middle East, there is considerable untapped potential for Europe to capitalise on these strengths through measures such as the Global Gateway – which aims to mobilise €300 billion to support infrastructure investment across the globe – and European Green Deal to advance renewable energy. The EU should see this effort to build up its influence and protect its climate, economic, and geopolitical interests as a strategic priority in the years to come.

European support for economic diversification and resilience against climate change is particularly important to Middle Eastern governments. To these ends, the EU could build new electrical interconnections across the Mediterranean, which would provide local employment opportunities and spur economic development – and, in turn, help address some of the causes of irregular migration and enhance stability. In the Levant, the EU could use its economic tools to support green energy connections between Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq. In the Gulf, the EU could put the European Green Deal at the centre of its diplomatic efforts to develop a joint preferential green investment area.

Europeans also have an opportunity to show solidarity with the citizens and governments of Middle Eastern countries that will experience the deepest food and energy price shocks resulting from the war in Ukraine. The countries that are most at risk from this – as they are most dependent on Ukrainian wheat – include Lebanon, Libya, Tunisia, Egypt, Jordan, Syria, and Yemen. This situation threatens to create further humanitarian crises in countries already suffering from economic collapse and state failure, which could spill over into Europe through increased migration flows.

The EU should help Middle Eastern states source and finance wheat supplies before shortages and high prices provoke crises and domestic unrest. The EU should continue its long-established – and important – role as a convener of funding conferences, but should also be more proactive in establishing global funding mechanisms to address food insecurity. The European Commission’s decision to fund a €225m Food and Resilience Facility to address the consequences of food insecurity and rising commodity prices in its southern neighbourhood is a big step in this regard, but it will need to significantly increase funding for the initiative.

Europeans should not be shy about publicising how this support benefits Middle Eastern states, aiming to amplify their influence. All too often, Europe’s considerable levels of aid and investment appear to be taken for granted by governments in the region. This contrasts with the approaches of Russia and China, which have skilfully emphasised the importance of their own contributions – even though these contributions have often fallen short of Europe’s in both quality and quantity. Europe will need to improve its strategic communications if it is to rebalance its relations with Middle Eastern states, which too often exploit its perceived reliance on them.

In addition, Europeans need to be more strategic in the conditions they attach to their regional support. European support has often been too bureaucratic, risk-averse, and focused on totemic issues such as human rights and high-level political reform. Far from giving the EU the means to achieve its goals, these conditions have proven relatively ineffective and have eroded its appeal relative to donors such as China and the UAE, whose support comes with far less stringent conditions.

A better strategy would be to focus European conditionality on strengthening more viable avenues for bottom-up reform, including by deepening cooperation with the private sector. This would prioritise principles related to good governance – often in less overtly political areas such as improvements in institutional efficiency that focus on anticorruption and the rule of law – rather than those that appear to undercut sovereign control and threaten governments’ hold on power (through, in essence, high-level political transformation). As part of this, Europeans should look for ways to bring together nations from the Middle East with their international partners, regional institutions, and Arab civil society organisations to discuss political and economic reform. This could involve reinvigorating the Union for the Mediterranean, which already provides Europeans with a forum to promote socio-economic development with their regional partners.

Perhaps surprisingly, financial conditions to improve good governance may even represent an area for some enhanced cooperation with Gulf Arab donors – who are growing increasingly tired of wasted investments in their regional partners. European and Gulf Arab states disagree on a range of related issues, but the European External Action Service could institutionalise a structured dialogue with GCC states on investments in regional stability. As a starting point, the EU could discuss a common environmental, social, and governance framework for such investments.

3) Stand up as a security partner

While Europe cannot hope to replace the US as the region’s dominant military power, European officials have raised expectations that the bloc will expand its security capabilities in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The last 20 years of failed Western interventions in the Middle East, coupled with the recent withdrawals from Afghanistan and Mali, underscore the limitations of military power in promoting long-term stability and good governance. But Europeans will still need to develop their security role in the Middle East if they are to protect their interests and address threats to regional stability.

As the US retrenches, European states need to present themselves as credible security partners and viable alternatives to Russia and China. They should pay particular attention to the Gulf, an area in which freedom of navigation and maritime security are of global importance. By strengthening the role of European navies in the Gulf, they would send an important political and military signal about their value as partners. The European-led maritime surveillance mission in the Strait of Hormuz, which has both naval and political arms, represents a good idea but has received too little political and material support from Europe to be taken seriously.

Europeans should also be more assertive in Libya. This should involve peacekeeping and demilitarisation operations around the ceasefire line, as well as leadership on security sector reform.

Given the region’s highly competitive marketplace for weapon systems, there is a pragmatic argument for Europe to build up its political and economic influence through arms sales. But, too often, arms sales do more to benefit European companies and Middle Eastern autocrats than to protect Europe’s strategic interests or stabilise the region. Besides greater end-use monitoring to ensure their weapon systems are not implicated in human rights abuses, European governments need to do more to prevent their use in any offensive capacity without prior consent.

France’s recent sale of Rafale fighter jets to the UAE was designed to boost Emirati air defence capabilities, reassure a strategic ally, build up European influence, and prevent rivals from filling the void. However, Europeans also need to do more to link their arms sales to political outcomes. In addition to deepening security cooperation with the UAE, France should have pressed Abu Dhabi to better support viable peace processes and regional stabilisation efforts, especially in Yemen and Libya. In this regard, the sale of French weapons was a missed opportunity.

4) Deepen transatlantic complementarity

Transatlantic unity remains important even as Washington looks to decrease its regional commitments and Europeans work to reduce their reliance on the US. While the US and Europeans have diverging regional priorities, it is still in their interest to cooperate on many issues. European states should try to preserve a strong US role on key issues, but will need to be more unified and commit more resources to the region if they are to be taken seriously in Washington.

The Biden administration should welcome this approach if it relieved the US of some of its regional responsibilities.[10] Europeans should not aim to draw the Middle East deeper into the competition between great powers, but the US should see an enhanced European role in the region as a valuable way to contain Chinese and Russian influence – and to demonstrate the West’s commitment to key regional partners.

Europeans should now look to recalibrate the transatlantic partnership based on mutual complementarity, focusing on maximising the benefits of joint political efforts, the US security role, and European economic instruments. This process could include a regular transatlantic Middle East and North Africa dialogue between political directors – one that extended beyond Washington’s current engagement with Berlin, Paris, and London.

To craft this new transatlantic relationship, Europeans will need to be more strategic in using their diplomatic, economic, and military tools to support US goals when these goals align with their own interests. On the security front, Europe should identify military contributions that can complement existing US capabilities and serve common objectives. The European naval presence in the Gulf should be well-placed to contribute to US efforts in the area, such as through the deployment of minesweepers. Similarly, Europe could deploy additional special forces and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance assets to support counter-terrorism and information-gathering operations.

Alongside this, Europeans should accept the fact that they need to devote more attention to the issues that are of most importance to them – particularly in North Africa and the Levant, which Washington has deprioritised. By demonstrating that they can be effective leaders in these areas, Europeans would allow Washington to focus its attention elsewhere. Their efforts in Libya and Tunisia will be an important part of this.

While Europe needs to act independently where it can, it will still benefit from US engagement on critical issues. In exchange for Europe stepping up when it matters, Washington should provide high-level political and economic support for European regional initiatives. Importantly, Europe should press the US to align its sanctions policy with European stabilisation efforts in places such as Lebanon and Iraq. There are signs that the Biden administration is already moving in a positive direction here, aiming to offset widespread US sanctions with more waivers and other pragmatic measures.

5) Avoid great power polarisation

The new geopolitical order requires Europeans to stand up for their interests in the Middle East, including in terms of competing for influence with Russia and China. But, where possible, Europeans should not reject possibilities to work with Moscow and Beijing to advance common goals, seeking to avoid a trajectory that sucks the region into destabilising great power competition.

Chinese investment and reconstruction support need not be a bad thing if it promotes regional development and stability. Europeans could pursue mutually beneficial regional initiatives such as those focusing on climate, food, and water security – which are key drivers of instability. There could be space for Europeans to work with the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), including through cooperation with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the European Investment Bank. The AIIB’s support for solar power in Oman is an example of what is possible when there are overlapping interests.

Coordination with China on some of these issues would also serve a strategic purpose. It would highlight the value of some ongoing cooperation with Europe and the potential downsides of a move towards closer alignment with Russia.

Coordination with Russia will become increasingly problematic under Putin. Nevertheless, there are narrow areas in which limited cooperation with Moscow may still be possible and useful. Europeans need to press for the restoration of the JCPOA despite the threat of Russian obstructionism. They should also try to prevent overt confrontation with Russia in countries such as Libya, while seeking to preserve space for humanitarian engagement in Syria.

It will be equally important for Europeans to demonstrate a willingness to work around Russia, including at the UN Security Council, if attempts at coordination falter. In Syria, for instance, European members of the council should aim to secure an extension of Resolution 2585 in July 2022, which facilitates cross-border UN humanitarian aid for Idlib. But they should be ready to deploy an alternative multilateral aid mechanism if Moscow blocks the resolution.

If Europe is to protect its key interests in the Middle East, it will need to display a willingness to coordinate with Russia – even in the face of the Ukraine conflict – and the assertiveness to lead on its own if required. This approach may help incentivise some Russian coordination, by making clear that Europeans are prepared to further isolate Moscow if it adopts a purely obstructionist stance.

Conclusion

Even as the world fixes its eyes on Ukraine, Europeans need to increase their engagement with the Middle East – a region that can be both a source of strength and vulnerability. Europe’s southern neighbourhood will be increasingly important in global rivalries that threaten its core interests related to migration, counter-terrorism, and energy. Europe will need to adopt a policy of principled pragmatism if it is to strengthen its standing in the region and more effectively compete against Russia and China, while holding its own against more assertive regional powers.

As part of this, Europeans will need to be more strategic in their use of financial, political, and security capabilities, particularly in the domains of green energy and economic diversification, and to reconfigure the transatlantic partnership around complementarity. They often have more to contribute in the Middle East than they give themselves credit for. If the EU or core groupings of European states can develop a more strategic approach to the region, they can become more influential actors. This approach would help them promote the stability and good governance that are vital to their interests, while guarding against external efforts to use Europe’s increasing interdependence with the Middle East against it.

- Julien Barnes-Dacey is the director of the Middle East and North Africa programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations. He works on European policy on the wider region, with a particular focus on Syria and regional geopolitics.

- Hugh Lovatt is a senior policy fellow with the Middle East and North Africa programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations. He advises European policymakers on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Israeli regional policy, and the Western Sahara peace process.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the numerous policy officials and experts from Europe, the US, the Middle East, North Africa, China, and Russia who have been so generous with their time and insights in the research for this paper. They are particularly indebted to Alistair Burt, Daniel Levy, and Nathalie Tocci for reviewing working drafts and providing their own ideas. As always, the authors are grateful for the support of their ECFR colleagues, including Mark Leonard, Jeremy Shapiro, Cinzia Bianco, Ellie Geranmayeh, Tarek Megerisi, and Janka Oertel. Finally, they owe special thanks to Elsa Scholz for her painstaking research assistance. Any mistakes or omissions are the authors’ alone.

ECFR would like to thank the foreign ministries of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden for their ongoing support for the Middle East and North Africa programme, which made this publication possible.

Source: This article was published by ECFR

[1] ECFR calculations based on “Global U.S. military deployment data: 1950-2020” by Michael Allen, Michael Flynn, and Carla Machain, 2021.

[2] Authors’ discussions with officials from European governments and EU institutions in 2020 and 2021.

[3] Authors’ discussions with US policy experts, 2021.

[4] Authors’ discussions with Chinese experts, Brussels, April 2022.

[5] Authors’ discussions with Chinese and Middle Eastern experts, Brussels, April 2022.

[6] ECFR interview with a Gulf Arab official via videoconference, March 2022.

[7] Authors’ discussions with policy experts and officials in Moscow, November 2021 and June 2019, and in Beijing and Shanghai, September 2019.

[8] Authors’ discussions with policy experts and officials in Moscow, November 2021 and June 2019; in Beijing and Shanghai, September 2019; in Gulf capitals, February 2020 and March 2018; and in Washington, February 2020 and October 2019.

[9] ECFR calculations based on European Commission data.

[10] Authors’ discussions with US policy experts, Paris, November 2021.

![Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken participates in the Negev Summit with Israeli Foreign Minister Yair Lapid, Bahraini Foreign Minister Dr. Abdullatif bin Rashid Al Zayani, Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry, Moroccan Foreign Minister Nasser Bourita, and UAE Foreign Minister Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed Al Nahyan on March 28, 2022 in Sde Boker, Israel. [State Department Photo by Freddie Everett / Public Domain]](https://www.eurasiareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/f-41-800x445.png)