The EU After The Elections: A More Plural Parliament And Council – Analysis

What is the new balance of power in the EU’s institutions following the May 2019 elections?

By Piotr Maciej Kaczyński*

The fallout of the May 2019 European elections is only just becoming visible. The European democracy is maturing and in the process many terms are being redefined. In this paper the author analyses the first weeks of European politics following the elections, particularly the higher degree of pluralism and politicisation of Europe’s institutions.

Analysis

The Europeans have spoken. George Soros, the embattled US-European businessman who has spent billions on pro-democracy projects across the continent, has summed it up best: ‘the silent pro-European majority has spoken’.1 What are the consequences of the end-of-May elections?

There are five top jobs to be filled in by the end of the year: Presidents of the European Commission, the European Council, the European Parliament and of the European Central Bank, as well as the High Representative for Foreign Affairs, are in the pool. The leaders in the European Council have decided to agree on them all in a single package that will reflect a variety of balances: geographical, political, institutional, of gender and of the size of member states. There are a number of names in circulation, including those of the Spitzenkandidaten process, especially of the two largest political families: Manfred Weber and Frans Timmermans, respectively the lead candidates of the European People’s Party (EPP) of the Socialists and Democrats (S&D).

The election results confirmed many expectations but also threw up a few major surprises. The most important was the improved turnout: some 220 million Europeans, 51% of all those eligible to vote, cast their ballots, the highest number in a generation and a clear sign that the European public is regaining its interest in European affairs.

The high turnout (up 8% since 2014) and the results suggest that the European leadership is regaining its democratic mandate after a number of national referendums in member states organised between 2015 and 2016. All of them –in Greece (on bailout in 2015), Denmark (on opt-outs, 2015), the Netherlands (on the EU-Ukraine trade agreement, 2016) and, most significantly, in the UK on Brexit in 2016– were failures from a European standpoint.

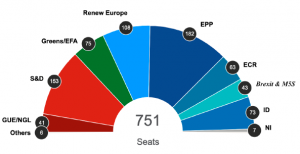

The first feature of the results is the end of the majority of the ‘grand coalition’ between the EPP and the S&D. Even if the political culture of the European Parliament is far more inclusive than in many EU member states dominated by the pro-government majority and opposition logic, the fact that the two largest political groups provided parliamentary stability in the Parliament was significant. Now, the two largest families have been joined by a third, liberal, group generated by a new large French contingent from President Emmanuel Macron’s party. Following its merger with Macron’s Republique en Marche the ALDE group has now even altered its name to Renew Europe (RE).

Seeking a new majority

The three political groups (EPP, S&D and RE) together could control the majority comfortably with around 440 MEPs. The same three political families also dominate the European Council. The three of them are virtually equal, as there is no majority in either of the institutions (Parliament and European Council) without one of them. Only together can they provide an effective functioning of the EU’s governance system.

However, the process of ‘leading candidates’ (Weber, Timmermans, and the liberals Margrethe Vestager and Guy Verhofstadt) pushes the current debate in quite a different direction. On the one hand there is a centre-left coalition ‘against Weber’, consisting of the social-democratic and liberal leaders in the European Council, most notably the French President Emmanuel Macron and the Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez.2 On the other hand, the German Chancellor Angela Merkel is firmly behind the EPP front candidate, also due to internal German politics, where the CSU outperformed in Bavaria and the CDU underperformed in the rest of the country. One politician said that the appointment of the Bavarian politician is of major significance to the CSU.3 Manfred Weber is working to build a coalition in his favour by extending his talks to the ECR leadership.

With the RE and the S&D claiming the support of the rest of the left-wing groups –the Greens and the GUE/NGL– against Weber, there is the smallest centre-left positive majority in the new Parliament (377 mandates). At the same time there is no majority with the EPP and ECR, even if the centrist group were to converge with it (353 mandates). This is when Weber might try to stretch his support by talking to the new far-right group largely comprised by MEPs elected in Italy (La Lega) and France (Rassemblement National). This, however, would be highly controversial amongst the more-centrist EPP as well as the RE, and hence unlikely.

The future of the EPP remains a mystery since the Hungarian governing party Fidesz, has been suspended due to its direct attacks against the group’s leadership during the European election campaign. Fidesz also stands accused of compromising European values, hence the suspension. Similar problems have arisen with Romania’s governing PSD, which is a member of the Social Democrats in the EU. The PSD leader Liviu Dragnea was recently jailed on corruption charges.4 The liberal Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš has also given rise to similar suspicions and there were recently a series of major rallies in Prague demanding his resignation.5

As of mid-June there are eight members of the European Council siding with the EPP (Germany, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia and Romania), six members with the S&D (Spain, Finland, Malta, Portugal, Slovakia and Sweden) and seven (France, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Slovenia) affiliated with the Renew Europe group. The Austrian Chancellor is running a care-taker government. Following the Danish elections, the new Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen (S&D) shall replace the previous liberal PM in the European Council, most likely still in June. The Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras is associated with GUE/NGL and announced snap elections for 7 July. The EPP is likely to pick up one seat in Athens. The Italian Prime Minister is not affiliated to any of the political families. The President of Lithuania, Dalia Grybauskaitė, an independent, will be replaced by a new leader in July, also non-partisan, Gitanas Nausėda. The Polish and British EUCO members are affiliated with the ECR.

It is very likely that by September there will be nine EPP members (+Greece), seven S&D members (+Denmark) and seven with Renew Europe. The majority in the European Council needed for the appointment of a new Commission President is 21.

Even if a centre-right or centre-left majority in the European Parliament were to be within reach, there is no majority possible in the European Council without all three of the political families. This is the first important message from the European elections: the only viable way forward is a ménage à trois.

The green wave

The elections brought a major surprise in that the two main blocks have been weakened while the two smaller centrist blocks are stronger, with the underlying threat from far-right nationalism. If the EPP and S&D were to become slightly smaller, the Liberals and the Greens would expand their European presence.

The status of the former has been strongly marked by the arrival of President Emmanuel Macron to the group: not only are 21 of the 108 group MEPs French, but the French arrival has led it into being re-named the group’s change into Renew Europe (RE). Dropping the adjective ‘liberal’ is not co-incidental. The new group leader is Dacian Cioloș, a former European Commissioner, who presented his own Romanian party PLUS last year to the world as located in the ‘centre, centre-right area’.6

The Greens were the major surprise in the elections. The party overperformed most visibly in Germany (25 mandates) and in France (12 seats), with a strong showing in less populous states like the Netherlands, Belgium, Ireland, the Czech Republic, Austria, Denmark, Finland and Sweden. With no presence on the European Council, the Greens’ strongest mandate comes from the main issue they promote: climate change. The Green parties across Western Europe have shown they enjoy the trust of the general public and the green vote should be interpreted as Europe’s citizens agreeing that climate change is the most pressing issue to be addressed.

Still, the Greens underperformed in the southern and eastern EU. Some commentators point out that the green agenda is not yet shared throughout the EU.7

The ECR

The other groups lost the elections. The GUE/NGL is much smaller than before with only Germany, France, Ireland, Greece, Spain, Portugal and Cyprus having two or more MEPs.

The groups to the right of the EPP are not as strong as anticipated. There were three groups in the previous Parliament. One of them, the EFDD, is unlikely to continue to exist in the European Parliament due to the problem of gathering MEPs from seven different countries. Effectively two big national parties are lacking a group at the time of writing: the weakened Five Star Movement in Italy and the temporary protest-vote Brexit Party from the UK. Should the Brexiteers have their way, they will depart from the European Parliament before 31 October 2019.

The ECR has also lost its third-place positioning in the European Parliament, currently being the sixth-largest group. Its most significant defeat was in the UK, as Britain’s Conservatives gained only four seats in the new Parliament. The internal group dynamics suggest it will be dominated by Poland’s governing Law and Justice party (PiS).

Open questions regarding the ECR include: will the Five Star Movement join the group? Should Fidesz leave the EPP, will it join the ECR? Will the ECR be included in the next European Parliament’s ordinary committee work?

The new far-right: Identity and Democracy (ID)

Before the elections some predicted that the far-right might obtain as many as 150 MEPs. This turned out to be an overestimate, but it was certainly viewed as a threat. Still, La Lega and Rassemblement National won the elections in Italy and France, respectively. Among their partners are the Finns Party (Finland), Alternative for Germany (AfD), the Freedom Party of Austria (FPO), the Belgian Vlaams Belang and the Danish People’s Party (DF). All in all, 73 MEPs from nine countries form the group.

EU politics

Politics in member states are usually exercised by various political actors, all based on a political party system and civil society. In the EU, however, there are three level politics. All of them take place at the same time and the final outcome of any process has to include all three levels.

The first level is the traditional party politics with which we are familiar at the national level. This is when the centre-right competes for power and ideas, support and influence, with the centre-left, liberals, greens, far-left or far-right, with single-issue-driven parties or otherwise. This level is best seen in the European Parliament, where the political groups negotiate between themselves all political appointments, agendas and solutions.

The second level of political relations is between member states. National interests and national perspectives, along with differing backgrounds, political culture, finances and history all come to the fore. Geography, size and experience tend to play a role in the interaction between the member states in the Council and the European Council.

The third level of political relations is between institutions. There needs to be a respect for the Parliament in the Council for there is hardly any respect for the member states in the European Parliament.

The many necessary balances

There are many different balances that must be respected in the EU. One is political, between the main political families. As argued above, the most likely compromise should include political figures from three European families: EPP, S&D and Renew Europe.

The second balance to bear in mind is geographical. In the past, the East was represented by the incorporation of Polish politicians: Jerzy Buzek became the President of the European Parliament in 2009 and Donald Tusk of the European Council in 2014. This time the South is callings for representation, linked to the departure of three Italian politicians –Mario Draghi, ECB, Antonio Tajani, European Parliament, and Federica Mogherini, High Representative– from their positions. Northern candidates are also being increasingly considered.

The entire issue is linked with the financial balance between net contributors, countries known for being stringent about their fiscal approach.

In the past a politician from a country outside the Eurozone could not claim the position of European Commission President (or, obviously, the ECB presidency). Size matters, too: compromises should not include politicians from Germany, France, Spain, Italy and Poland alone. The absence of the larger countries from appointments would safeguard the rights of the smaller.

In addition, there is the need for a gender-balanced approach. Donald Tusk, the President of the European Council, mentioned that two women should be expected to take leading positions.8

Tusk was formally appointed formateur on 28 May.9 Soon after, however, a system of informal party negotiators was created with two negotiators on behalf of the EPP (Croatia’s Andrej Plenkovič and Latvia’s Krišjānis Kariņš), two on behalf of the S&D (Spain’s Pedro Sánchez and Portugal’s António Costa) and two on behalf of Renew Europe (the Netherlands’ Mark Rutte and Belgium’s Charles Michel).

All of the European Council’s work should be completed before the new European Parliament’s first plenary sitting takes place in Strasbourg on 2 July. Should that be the case, the next balancing act will be necessary: the interinstitutional, affecting the European Parliament. It is not known how the European Parliament –currently in the process of self-organisation– will react to a European Council appointment if the EUCO disregards the Spitzenkandidaten process.

The June 2019 European Council voted for the three candidates of the largest political families, but none of them gained the more than 21 votes necessary, despite Timmermans and the liberal candidate Vestager being supported by the S&D-RE and the Greek PM while the EPP’s Weber was only backed by his party peers.10 Nevertheless, all were rejected at the 20-21 June 2019 European Council.

Should the next European Council be able to put forward a candidate for the Commission Presidency, there is a significant chance it will not be one of the leading candidates. ‘A more moderate EPP candidate’ could be acceptable for the left, according to one member of the European Council,11 and the EPP seems to be pushing for the next Commission President to be from among its ranks.

This is where other options need to be considered, rather than seeking a balance. The new candidate will need to be consensual, gaining the support of the EPP, S&D and Renew Europe: probably an EPP politician who is not Manfred Weber. At the time of writing one name comes to mind, that of Michel Barnier, who as a French citizen and an EPP politician could gather support from both the Berlin and Paris governments.

Still, to seek such an agreement is a matter of European Council internal politics. The candidate needs to win both institutions’ approval. Michel Barnier was not a candidate in the elections. Will the Parliament oppose him on the principle of institutional balance? On a positive note, he is highly respected in the EU for his commitment to the European interest in the negotiations over Brexit with the British government.

Conclusions

The elections to the European Parliament are providing a strong mandate for EU reform. The change people want, however, is not unidimensional. Those who voted for sovereignist parties have a different perspective from their opponents, mostly the green electorate. The anti-Europeans are softening their narrative, also in the context of the new post-Brexit realities. The centre-right and centre-left are seeking stability and maintain the status quo. As Ivan Krastev recently remarked, ‘everybody wants a change, but a different one’.12

Nobody debates the democratic deficit of the European project anymore. This clearly suggests that a major increase in turnout means there is a greater democratic mandate for the EU institutions to act. But the context as to how and on what to act will require some handcrafting, since the many expectations are sometimes contradictory.

The next question to be addressed is not only who should lead the work of the Commission and other institutions, but also how. Will the next Commission be a political one? If so, in what way? The Juncker Commission’s experience has been very telling. There were controversies but the Juncker College was clearly a step up in the politicisation process. Still, not everyone is in favour of the Commission’s increased politicisation. For one thing, it is a challenge for a political Commission to maintain impartiality in certain important areas, such as competition policy; if the motivation for acting is political it is difficult to defend it against the accusations of its independence being compromised.

The new European Commission may not be as liberal-minded as previously, depending on the new majorities in the European Parliament and the European Council. On the one hand, the UK’s departure may have a significant impact on the negotiations at the Council of Ministers. On the other hand, the treaties have been written in such a way that building a social Europe, for example, will be limited if there are no changes in the treaties, while there are still many of areas that could be liberalised.

The agenda of the next European Commission is currently under negotiation. The June European Council adopted the ‘New Strategic Agenda 2019-2014’13 and in the European Parliament there are agenda negotiations involving four groups: EPP, S&D, RE and the Greens. Some have dubbed the policy priority negotiations a coalition-forming process similar to government-forming in countries like Belgium or the Netherlands.14 The process will be finalised with the presentation of the new Commission President. Five and 10 years ago the documents were known as Political Guidelines for the Next European Commission.15

If a political Commission is the reality, then enhancing European democracy is the next challenge. Among the issues debated during the elections was the idea of allowing the European Parliament to present its own legislative proposals, breaking the European Commission’s quasi-monopoly. Another idea for enhancing European democracy is to change the Union’s communication policy. So far it has largely focused on the role of member states being responsible for communicating the ‘EU’ to its citizens. While this might have been largely successful in places like Germany or Belgium, in many other counties that has not been the case. For instance, regarding the Brexit campaign in the UK, President Juncker admitted it was a mistake to entrust the communications policy to the British Prime Minister: ‘It was a mistake not to intervene and not to interfere because we would have been the only ones to destroy the lies which were circulated around. I was wrong to be silent at an important moment’.16

The new European Commission needs a new communications policy with the EU’s citizens. The Union must become a more concrete reality. The stakes are very high for the EU’s citizens and thus they have real alternatives: on security, jobs, the economy, climate and many other vital issues. Their input should not be set aside for a five-year-long halt. There is a need for a new set of instruments to be developed by the European executive and that will be on the agenda of the next European Commission.

*About the author: Piotr Maciej Kaczyński, Independent expert on EU affairs | @pm_kaczynski

Source: This article was published by Elcano Royal Institute

1 George Soros (2019), ‘Europe’s silent majority speaks out’, Project Syndicate, 7/VII/2019.

2 ‘Sánchez sides with Macron to thwart Weber’s European Commission bid’, Financial Times, 29/V/2019.

3 Interviews in Kielce, 9/VI/2019, and in Berlin, 11/VI/2019.

4 ‘Romania corruption: PSD chief Liviu Dragnea jailed’, BBC, 27/V/2019.

5 ‘Tens of thousands rally in Prague in biggest protests since Velvet Revolution’, Euronews, 23/VI/2019.

6 ‘Domnul Dragnea n-are dreptul să arunce în aer societatea românească’, PressOne, 17/XII/2018.

7 Ivan Krastev (2019), ‘After the European elections where is the European Union headed?’, Heinrich Böll Stiftung, Berlin, 3/VI/2019.

8 ‘Women should fill two EU top jobs, Tusk says’, EU Observer, 29/V/2019.

9 ‘Informal dinner of heads of state or government’, European Council.

10 ‘Tsipras: unlike Weber, Timmermans and Vestager had wide support’, Euractiv, 21/VI/2019.

11 Ibid.

12 Krastev (2019), op. cit.

13 ‘A New Strategic Agenda 2019-2024’, European Council, 20/VI/2019.

14 Interview with Professor Steven Van Hecke of KU Leuven, 22/VI/2019.

15 Jean-Claude Juncker (2014), ‘A new start for Europe: my agenda for jobs, growth, fairness and democratic change. Political guidelines for the next European Commission’, 15/VII/2014; and José Manuel Durão Barroso (2009), ‘Political guidelines for the next Commission’, 3/IX/2009.

16 ‘Juncker regrets EU silence on Brexit campaign “lies”’, Reuters, 7/V/2019.