Afghanistan Power Struggle: A Make Or Break Situation? – Analysis

By Chayanika Saxena*

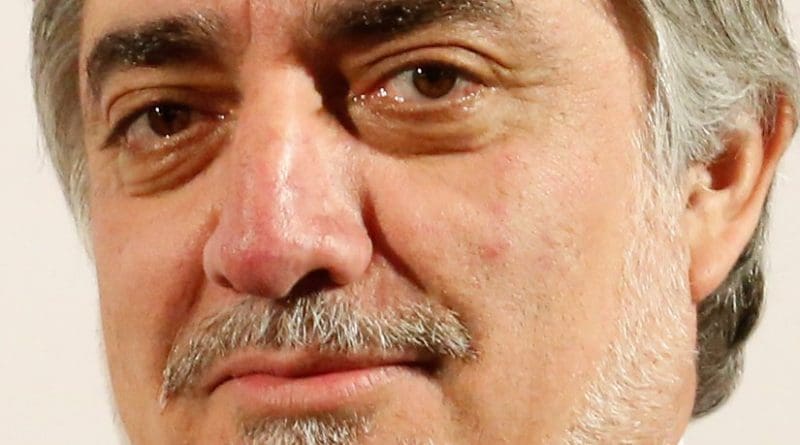

Yet another round of quarrel shook the already feeble political structures of Afghanistan as the Chief Executive of the National Unity Government (NUG), Abdullah Abdullah, in a public outpouring, criticized the President of the country for having failed to meet many expectations, including not having given personal audience to him in the last three months.

This outburst against Ashraf Ghani, with whom he shares political power in a two-pronged government that is currently heading Afghanistan, appears to have happened for two equally probable reasons. One, it could have been a result of genuine disappointment at not having been taken seriously in the government that he was ostensibly supposed to lead in an equal measure. Two, it might also have been an attempt to placate those in his constituency who think that he has not done and delivered enough.

Cobbled together under the supervision of the United States, NUG assumed political power in Afghanistan on September 21, 2014, following extremely controversial Presidential elections that saw Ghani and Abdullah trade charges of corruption, nepotism, rigging and the like. The run-offs to the final elections were immensely heated, with local and international observers raising questions about the freeness and fairness of the polls that were conducted between the months of April and July 2014. In fact, the breadth of allegations related to electoral fraud did not even spare the head of the secretariat of the Independent Election Commission (IEC), Zia ul-Haq Amarkhel. It was alleged that Amarkhel was involved in the ‘fattening of the sheep’- a euphemism for what the Abdullah camp believed stood for stuffing of ballot boxes with fake votes in support of his rival, Ghani. While no separate inquiry was set up to look into this scandal then, but the ‘Amarkheli gate’ that this incident came to be known as was resolved only with the intervention of United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) and the subsequent resignation of the IEC head.

Beset with troubles as it was being conducted, the conclusion of the 2014 Presidential elections did not bring any respite to the political insecurity that was compounding the economic, social and security woes of Afghanistan in 2014. The election results – both provisional and final – were dismissed by the Abdullah camp as fraudulent, eroding whatever little public faith that the official electoral watchdogs in Afghanistan enjoyed.

It was alleged by Abdullah, who had a substantial edge over his Presidential rival, Ghani in the first run-off, that the provisional results which showed the latter in the lead was an outcome of massive electoral rigging; a charge to which even the EU (and other international monitoring agencies) conceded. Yet, just a few hours before the election results were due to be announced, a deal brokered by John Kerry, established a ‘unity’ government with an ‘initial span of 2 years’. Standing for all but unity, this government was essentially an attempt at staving off inter-ethnic conflict in Afghanistan by placating the major constituencies that the two contenders were believed to represent – Ghani and Pashtuns and Abdullah and Tajiks.

Having lost the 2009 round of elections to Karzai and having achieved an incomplete and unsatisfactory victory in the Presidential elections of 2014, Abdullah Abdullah had to be content with what was handed to him in September 2014. This defeatist victory however, had some silver linings to it – or as they may have appeared to him – and which were assurance of equal share and say in power and an expiry date. The deal that was brokered between the self-styled leaders of the two major ethnic communities in Afghanistan was premised on some commitments, chief of which were expected to bring about (i) constitutional changes that would formalize and institutionalize the position of Prime Minister; (ii) electoral reforms, including the disbanding of the then (and existing) IEC, and (iii) equality in allocation of ministerial portfolios, within 2 years from the installation of NUG.

De-jure, while the agreement appeared to have placed the two leaders on par with one another, de-facto, it was the President of Afghanistan who came to have the final say on most of the issues. Working within a Presidential format of government, the President of Afghanistan is constitutionally vested with powers (such as Decrees) that can ensure the implementation of decisions in many matters. It also needs to be noted that the position of the CEO was essentially created as an exception with little constitutional basis and validity to back it. As a result, the ensuing power struggle that took place between them, especially in the (almost) absence of constitutionally provided mechanisms for dispute resolution, meant that the country would stare at deadlocks in variety, and it did.

To begin with, the immediate cabinet, or what is called the ‘Executive’ in formal political parlance took almost two years to be commissioned in entirety. As envisaged under the agreement, the allocation of portfolios was to be an equally divided task and required approvals and vetting from both the heads. While getting the two to agree on the candidates, especially for critical ministerial berths, was in itself a challenge, the National Assembly of Afghanistan was another hurdle to be cleared to instate ministers and their deputies. The resultant delays implied that Afghanistan functioned without a Defense Minister until the last month.

Electoral reforms, which were to pave way for the conduct of Parliamentary and District elections and ultimately, lead to the convening of the Loya Jirga (Grand Council) for working on constitutional change, were another bone of contention between Ghani and Abdullah. It was decided at the time of the installation of NUG that a temporary Special Electoral Reforms Commission (SERC) will be incepted with immediate effect to draft recommendations for changing the electoral landscape of Afghanistan, which in its given avatar, was (and is) susceptible to easy and colossal fraud. Where it took the primary decree to install this commission a good five months to be passed, this commission did not begin working until June 2015. The difference in opinion between the President and CEO over the chairman of this commission kept it out of job since March 2015 when its composition was first approved. This commission worked under the supervision of Abdullah and advanced 11 recommendations of which 7 could pass the President’s muster. The current position of electoral reforms in Afghanistan is however, in limbo since the Wolesi Jirga (Lower House) of the National Assembly has refused to ratify the reforms even as Parliamentary elections in Afghanistan are around the corner.

Another grievance of Abdullah was of the shunting and replacement of his chosen/nominated people and even closing down of offices and administrative berths that were occupied by those who were ostensibly close to him. For instance, as quoted in the New York Times, one of the possible reasons behind the recent public outburst was the belief that the administration under the NUG has been disproportionately (and unfairly) cornered by Pashtuns, particularly the Ghilzai Pashtuns, who form the base of Ghani’s immediate political constituency. The rumored closing down amalgamation of the Afghan Chambers of Commerce and Industries run Qurban Haqju, who is believed to have helped Abdullah in his elections, is one such instance that could have left the CEO upset over his lack of substantive authority and privileges in NUG.

To top this, their ways of dealing with the Taliban insurgency and the foreign policies of Afghanistan have often been at odds. Where Abdullah is not in favor of political mainstreaming of Taliban as much as Ghani is, his opposition to kowtowing Islamabad and Rawalpindi too fell on deaf ears. Abdullah also claimed that “over a period of three months you (President) don’t have time to see your chief executive one-on-one for even an hour or two? What does your highness spend your time on?”

This public expression of disappointment and exasperation over the limited role, authority and privileges that Abdullah has been accorded reflects that the unity within the NUG is but for the sake of name. While some observers suggest that this public display of aggression was done to assuage those who had supported Abdullah, but who now sit dismayed at having earned little from this extension of support, there are some who believe that these are genuine grievances. In all however, as the ‘original deadline’ that was assigned to NUG’s tenure stands just a month away, these quarrels, if not managed, could precipitate into a consuming power struggle. Or, they may as well herald the changes that the NUG and people of Afghanistan have been waiting for two years – reforms, accountability, transparency and betterment.

*Chayanika Saxena is a Research Associate at the Society for Policy Studies, New Delhi and Web Editor of South Asia Monitor. She can be reached at: [email protected]