Religion And Politics Of Power In Iran – Analysis

The only theocracy of its kind, Iran is somewhat of an oddball among the variety of states in the international community. The country is host to a system of governance that, at least in structure, is reminiscent of a modern democracy all the while being steeped in conservative Sharia law.

After the end of Cold War, Iran adapted elements of democratic governance into the framework of conservative Sharia law. Thus, the country today is led by an army of clergy that have influence over nearly every aspect of Iranian life. The supreme leader, who sits at the top of the hierarch, serves as the Chief Islamic Jurist who guides the country in the absence of the next great Imam of the Shia faith, Imam Mahadi.

This concept of the Velayat-e-faqih was introduced after the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and was popularized by the first ayatollah, Ayatollah Khomeini, in a bid to justify Islamic and clerical rule in the Persian heartland. Since then, Islamic theocracy has evolved from being an experiment of a burgeoning Middle Eastern state to the deep-seated bureaucratic and social reality of Iran, regardless of whether the country was experiencing a conservative or progressive current.

This brief will attempt to outline the contours of this administrative and societal reality by considering the set-up of the Iranian government, and the influence its key institutions and people have on Iranian society.

The Iranian Government and Clerical Influence

While only a small segment of the Iranian clergy is explicitly involved in regime politics, these regime clergymen are intricately woven into the multi-tier government set up of the Iranian state. Reminiscent of its western counterparts, the Iranian government too can be separated into multiple branches with each branch having some level of check on the other.

At least on paper this system provides for a distribution of power away from the supreme leader and between various entities of the government. These primary centers of power include: 1) The Supreme Leader, 2) The President, 3) Iran’s legislative assembly, The Majlis, 4) The Judiciary that handles non-constitutional cases, 5) The Guardian Council that handles constitutional matters, 6) The Assembly of Experts that handles the election of the next Supreme Leader, and finally 7) The Expediency Council that serves to resolve disputes between the Guardian Council and the Majlis. In this reality, this distribution of powers serves to disempower political or ideological faction that do not concur with the Islamist view of governance that the establishment holds.

While the clergy occupies nearly all branches of government, a few stand out for the influence they hold in shaping politics and society. These can be further thought of as formal and informal mechanisms. The Supreme Leader, The President, The Guardian Council, and The Iranian Revolutionary Guard represent the most powerful formal mechanisms for the clergy to create and implement policy. The informal linkages include informal groupings of powerful clergy, connections formed through intermarriage, use of patronage, etc.

Formal Linkages

The power of the Supreme Leader emerges from his status as the Faqih or the chief Islamic jurist. Inherent in this title is the knowledge the Supreme Leader is said to posses of the Quran and of Islamic theology. Thus, the status of the supreme leader as a jurist can provide him with significant leverage on policy making and in setting the direction of the country.

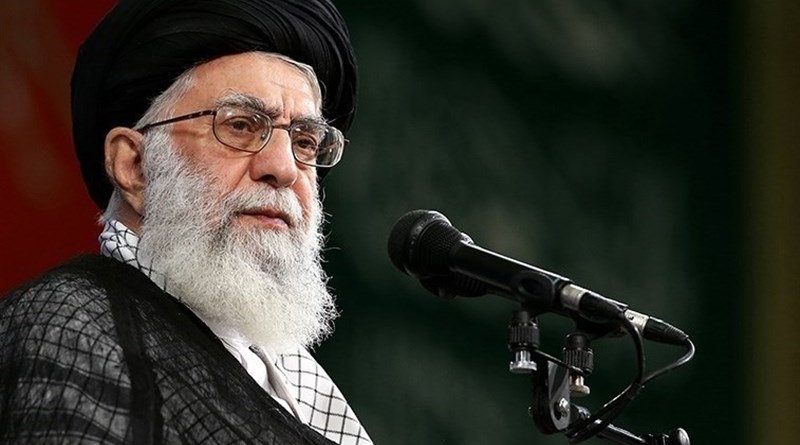

Following a lowering of requirements for the position of the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei emerged into power after Ayatollah Khomeini’s death. However, this created criticism surrounding his qualifications as the faqih. Consequently, Khamenei’s power and legitimacy within the government and nationally was compromised relative to his predecessor, Ayatollah Khomeini.

Alternatively, to some politicians Khamenei made an ideal candidate precisely because they believed that his low credentials would make him easier to control. Since his selection Khamenei has struggled to show a united Iranian front to its allies and enemies internationally as the country continues to be mired in popular protests and internal politics. Nonetheless, it would be short sighted to forget that the Iranian constitution still provides him with a rather large range of powers.

Khamenei’s rise to power, despite his lackluster religious qualifications and the country’s poor performance, is also attributed to the support of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corp (IRGC) whom he had helped gain remarkable power in Iranian polity. The Corp was established under the constitution to guard Iran’s borders and fulfill the ideological mission of jihad and the organization has regularly used ideological indoctrination for recruitment purposes. One of its units, the Basij Resistance Force, was known for recruiting young cadets at mosques and giving them intense ideological training. The two share a somewhat mutualistic relationship, though analysist often state that the IRGC holds more power than most Iranian institutions and has a strong grasp on the economy.

Further power lies in the hands of the Guardian Council that decides on matter of constitutionality of laws or fatwas passed by the Majlis. The Council consists of 12 Islamic jurists, six chosen by the Supreme Leader and six chosen by the Judiciary and confirmed by the parliament. In this way the Council can have a very direct influence on the social policy that directs everyday life.

Considering that the Quran and Sharia law form the rule of the law in Iran, the Guardian Council, in determining constitutionality, is endowed with the power to interpret if religious texts allow bills to translate into national policy. The Council is known to have a conservative leaning and its judgements have attracted international criticism.

In 2017 the Guardian Council moved to state that it was against Sharia for non-Muslim candidates to run for office in Shia majority constituencies. As a consequence a local court decided to remove an elected official of Zoroastrian origin out of office, inviting the condemnation of rights groups like Human Rights Watch.

Additionally, the Guardian Council is also central in judging if parliamentary or presidential aspirants are loyal to the regime and have the requisite knowledge on Islam. This has become a point of contention between the conservative Council and the reformist ruling government. In early 2020 Iranian president, Hassan Rouhani, spoke against the Council for disqualifying thousands of current and prospective parliamentary candidates, a large number of whom are progressive Islamists, by stating that running hundreds of candidates from only one faction is “not an election”.

Informal Linkages

Informal linkages between clerical leaders are common in Iran due to the country’s reliance on patronage networks. While there are nearly 28,000 hojjatoleslam clerics and 5000 Ayatollahs in Iran, only 2000 and 80 of them respectively are part of regime politics.

Even within the ranks of these clerics the most influential form cliques of their own. Gregory Giles terms this system as Iran’s “four rings of power”. The central ring consists of the clerics that are closest to the Ayatollah and consist of top state officials from all major branches of government. Thus, according to Giles, these linkages are maintained not only due to “their status as Shia clergy, but also their personal connection to the Ayatollah and their common struggle against the Shah”.

For instance, the current Ayatollah is a disciple of former President Mohammad Khatami’s father Ayatollah Khatami. Further down the power structure, top ministers from the military and intelligence bureaus are frequently graduates of the theological schools in Qom, such as the Madrasse-ye Haqqani. Giles also highlights that intermarriage between influential religious families and IRGC commanders is a common way to build wider patronage networks. These patronage networks become an easy way to station familiar individuals in government posts.

Crisis in Clerical Leadership

In recent decades, the Iranian government has gone through waves of hardline and progressive governments. Traditionally politicians use their religious and revolutionary credentials in political campaigns. Vast patronage networks of clerics also help. However, the popularity of Hassan Rouhani, at least at the time of his re-election, indicates that people are also receptive to progressive leaders that opt for “softer” diplomatic approaches.

Nonetheless, neither progressive nor hardline governments have been able to bring substantive economic development or improve the standard of living for the modern Iranian. This has led to widespread dissatisfaction with the Iranian government, especially among the younger generation, which is demanding progressive rights. Preceding governments led by President Mohammad Khatami, a progressive, and President Ahmadinejad, a conservative, have both failed to produce economic growth in a country that is under a range of international sanctions. Rising popular frustration and internal discord put these individuals out of office. However, as a survey conducted in Tehran indicated, this may not have necessarily indicated popular disillusionment with Islamic rule itself, but their dissatisfaction with the existing clerical administration’s corruption, unaccountability, and ineffectiveness.

Tension between religious factions within the government is another cause for gridlock and slow change in Iranian society. Past presidents have constantly clashed with the clergy creating a changing network of alliances between key politicians. For example, due to former president Mohammed Khatami’s political reform, the suddenly weaker clergy created stronger alliances with the military and the judiciary.

In Khatami’s case journalists and Islamic scholars have used media to sway public opinion, stating that Khatami was unable to fulfill his campaign promises. This sentiment gained traction in the public and was one reason Khatami was not re-elected. His successor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s terms were marked by intense rivalry between him and the Majlis. The parliament regularly rejected his cabinet nominees and stalled on signing off, and later shelved, the Targeted Subsidies Plan of 2009-2010 which was one of his flagship economic measures by stating that the plan would lead to unmanageable inflation. Ali Larijani, speaker of the Majlis, and Ahmad Tavakoli, a conservative populist parliamentarian, among several other politicians also made public statements bashing Ahmadinejad for violating laws. One majlis record stated that the Ahmadinejad government had only abided by 59% of the 159 laws passed.

As is clear through the ideological and political leanings of previous presidents and government, that the swing back and forth between conservative and reformist every election cycle has become somewhat of a staple.

Today, Rouhani, who followed Ahmadinejad, and his progressive colleagues face a similar crisis. Rouhani’s once favorable public perception has taken a turn for the worst. In 2019 Iranians turned out in huge numbers to protest the Rouhani administration’s decision to increase petrol prices in response to the country’s floundering economy. Hardline politicians in Iran are also criticizing Rouhani’s diplomatic approach to the issue of economic sanctions and Iran-US relations. All this has caused his approval ratings to drop as well.

Internally, according to intellectuals of the progressive reform movement, the “crisis began when they surrendered the vetting of candidates to the ultra-conservative Guardian Council”. The progressive groupings are thus facing a dwindling base of candidates and pressure to accommodate conservative interests. It is yet to be seen if the movement will get through the next elections cycle.

Conclusion

From directing minute details for daily life to controlling institutional politics, the Iranian clergy wield great influence in politics and government. After the Iranian revolution in 1978, Iranian society went through a momentous change that changed Iranian society.

However, the religious fervor and patriotism that started and upheld the revolution and its revolutionary changes, is starting to die down. The new generation of Iran, who have never lived through the revolution, does not relate to religious conservatives who still function by the same old equations and are instead demanding progressive reform in the government.

On the other hand, people are also frustrated with the progress faction’s inability to keep its promises and as the US left the JCPOA, matters were only made worse. This tension is visible in the politics of the clergy in the government as well as progressive and conservative factions vie for power. It is unlikely that this tension will die down until an administration is able to bring economic stability to Iran. Whatever the ideological leaning of these politicians may be however, the theocracy is likely to survive.

*Swati Batchu, Researcher, Center for Security Studies, O.P. Jindal Global University

Very lucid article.Well presented .