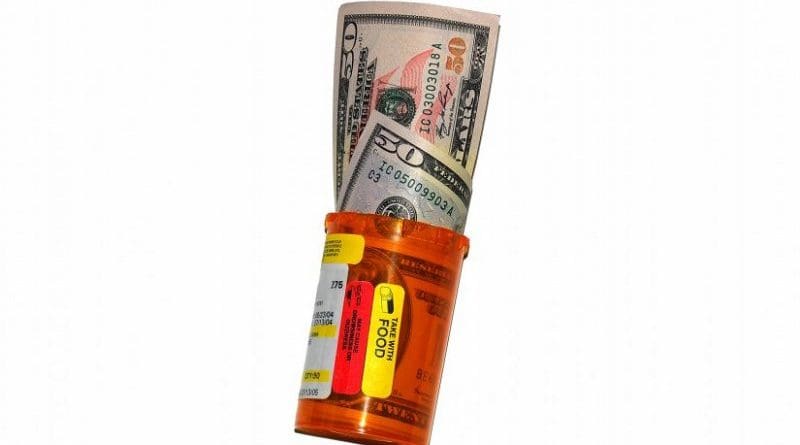

Miracle Cure Costs Less Than A Budget Airline Flight

The revolution in generic drugs means that a 12-week course of drugs to cure hepatitis C can be manufactured for just US$50 – as low as the cost of a plane ticket on many low-cost airlines. Furthermore, new data shows that these generic copies are just as effective as the branded medicines. Yet restrictions and patent issues around the world mean that hardly any patients can access the drugs at these low costs, say experts speaking at the World Hepatitis Summit in Sao Paulo, Brazil (1-3 November).

“As there are around 70 million people infected with hepatitis C worldwide, the basic cost of the drugs to treat everyone infected globally, at $50 each, would be around US $3.5 billion,” explained Dr Andrew Hill, a pharmacology expert from the University of Liverpool, UK. This represents less than a fraction of 1% of the global health budget of some US$ 8 trillion. “Much more must be done to enable all countries — but especially developing countries — to produce or buy drugs for these lower prices. Without significant changes to pricing structures, the battle against the global hepatitis C epidemic simply can’t be won.”

In his presentation, Dr Hill will present data on the hugely varying cost of a 12-week course of sofosbuvir and daclatasvir, a common combination of the new directly acting antiviral drugs (DAAs) that have revolutionised hepatitis C treatment by providing rapid cure with few or no side effects. The list price for this combination of drugs ranges from close to cost price in India ($78) and Egypt ($174) to $6,000 in Australia, $77,000 in the UK, and a staggering $96,404 the USA. Yet the basic cost of the active ingredients, including formulation and packaging costs and even allowing a small profit margin for the generic companies brings the basic cost down to under $50 per course.

In high-income countries, most of which have treatment restrictions allowing only those with advanced disease to be treated first, some infected patients have resorted to buying generic drugs from international buyers’ clubs (who buy in bulk from developing countries) or directly from countries where they are manufactured. For example, in the UK, those not wanting to wait for advanced disease to be treated have been able to legally purchase a 12-week generic course for prices ranging from US $1000 to $1200. Research studies on these patients show that cure rates are as high as for the branded medicines, ranging from 90% to 95%.

An analysis presented at the summit on the efficacy of generic DAAs looked at 1160 patients who have imported DAAs for personal use into 88 countries on 5 continents. Data from these patients show that cure rates are well over 90%, the same as for the branded products, but at a fraction of the cost.

“In 2016, for every person cured of hepatitis C globally (1.76 million), another person was newly infected (1.5 million). We simply cannot eliminate this epidemic unless we treat more people. And we can only do this if the prices of the drugs come down,” explained Dr Hill.

He added that the manufacturers of DAAs must do more to provide voluntary licences in countries that do not currently have them for generic companies to produce cheaper (but just as effective) generic DAAs. This is what has happened in Egypt, which had nearly 7 million people to treat, but now have fewer than 5 million. However, more than half of those people infected globally live in countries with no voluntary licence to allow generic production. “For example, China and Russia, two countries with very large hepatitis C epidemics, have no voluntary licence in place to produce cheap generic drugs,” explained Dr Hill.

However, Dr Hill makes clear that any efforts to reduce drug prices and enable mass generic DAA production worldwide will be futile unless countries also step up their efforts to find and diagnose their infected populations. “We cannot treat people if we do not know who they are,” explained Dr Hill. “Countries must massively step up their screening efforts, or they will simply run out of people to treat – a diagnostic ‘burn-out’. The proportion of patients with hepatitis C who know they have it ranges from 44% in high-income countries to just 9% in low-income countries.”

He concludes that lessons can and should be learned from the HIV epidemic to successfully end the hepatitis C epidemic worldwide. “It has taken the world 15 years to get 19 million people globally on antiretroviral treatments for HIV,” he said. “We already have the drugs necessary to eliminate hepatitis C. Let’s learn from the past, and repeat the medical success story of global HIV treatment.”