Managing Indonesia’s Commodity Windfall For Long-Term Benefits – Analysis

By ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute

Despite the adverse economic shocks in the global economy, inflation in Indonesia is still relatively under control and growth is returning to the pre-pandemic trajectory although a looming global economic recession next year and geopolitical uncertainties continue to pose a threat to the economy.

By Maria Monica Wihardja and Suryaputra Wijaksana*

INDONESIA’S PERCEIVED IMMUNITY FROM GLOBAL ECONOMIC WOES

The global economy is still clouded by an uncertain and unfavourable economic and political climate. High inflation – mostly in food, energy and fertiliser – is resulting from supply chain disruptions related to Covid-19, which started in mid-2020, and a post-pandemic uptick in demand (see Figure 1).

This high inflation has been compounded by the war in Ukraine – which has particularly affected wheat, maize, vegetable oil, and fertiliser (Vos, 2022) – and extreme weather. Although food inflation had tapered off by mid-2022 to pre-war levels, the risk of price surges and continued volatility in food, energy and fertiliser prices remains high.

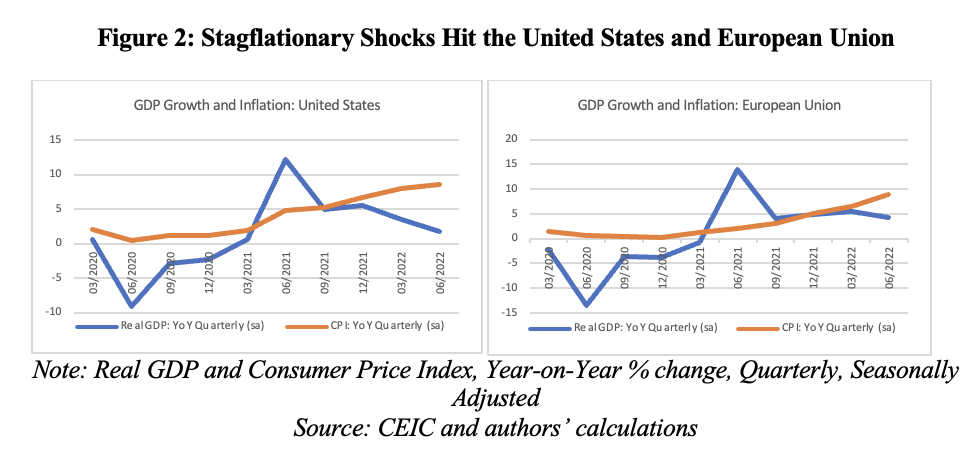

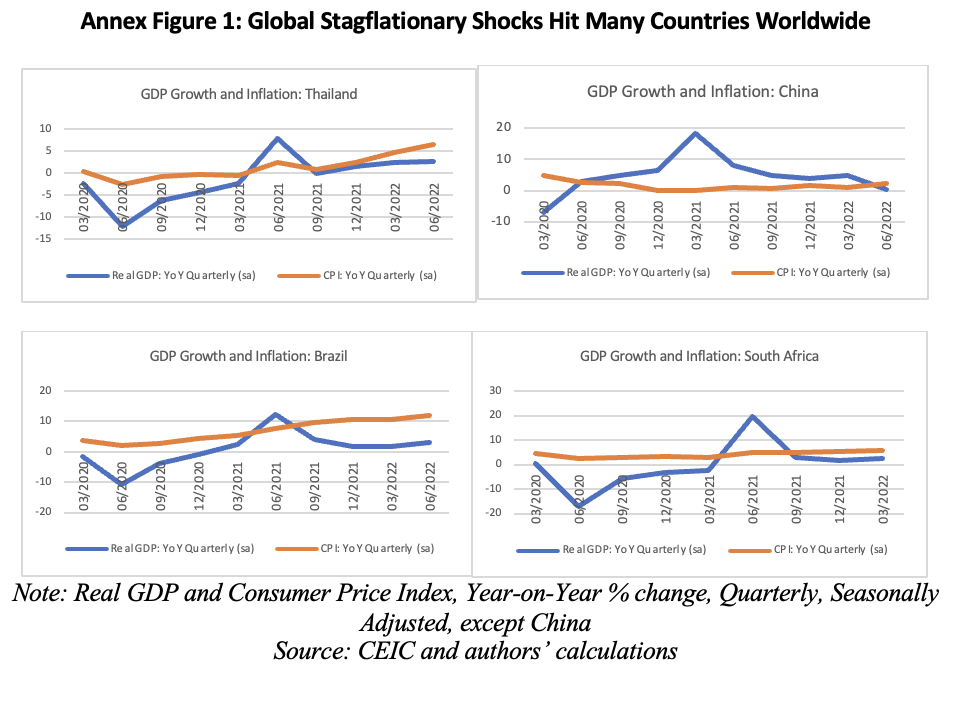

Many central banks, including the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank, are responding to the high inflationary environment by increasing interest rates to reduce demand.[1] As a result of tighter monetary policies, some countries are showing signs of stagflation, with rising inflation and declining GDP growth. This includes the US and European Union (Figure 2) as well as many emerging countries such as Thailand, China, Brazil and South Africa (Annex Figure 1).

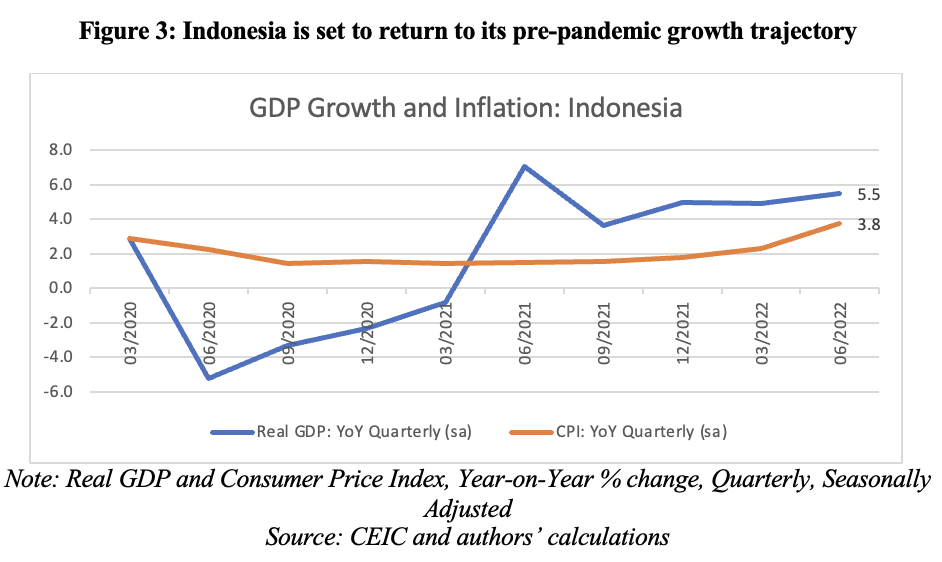

Despite the gloom in the global economy, the World Bank projects Indonesia’s economy to grow by 5.1 percent in both 2022 and 2023 (World Bank, 2022). In fact, the country is set to return to its pre-pandemic growth trajectory of 5 percent (Figure 3). This is relatively high compared to the case for other G20 countries, which, as a group, is predicted to only grow by 2.5 percent this year and 2.1 percent in 2023 (Moody’s Investor Service, 2022). Moreover, inflation in Indonesia is still under control, at least until recently.

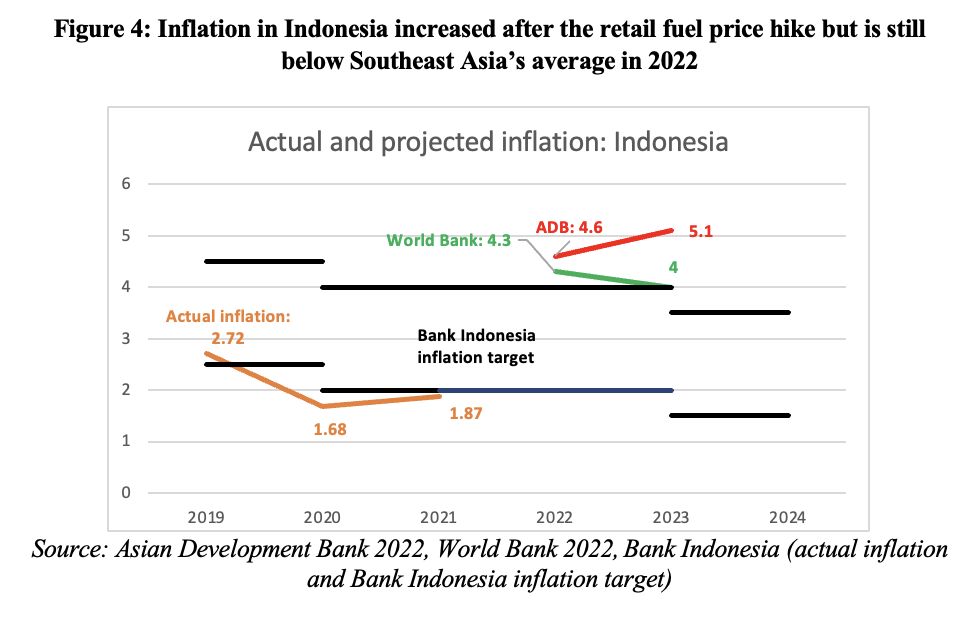

On 3 September, the government decided to cut some fuel subsidies and increased fuel prices by about 30 percent. After the subsidy cut, the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank revised Indonesia’s projected inflation from 3.6 to 4.3 percent (World Bank, 2022) and 4.6 percent (ADB, 2022) respectively (Figure 4). The government of Indonesia has also revised its projected inflation for 2022 from 3 percent to between 4.5 and 4.8 percent in 2022 (Liputan6, 2022). Compared to the projected 5.2 percent inflation for Southeast Asia and 4.5 percent for developing Asia in 2022 (ADB, 2022), Indonesia’s inflation is considered relatively manageable.

COMMODITY WINDFALL HELPING INDONESIA MANAGE GLOBAL SHOCKS

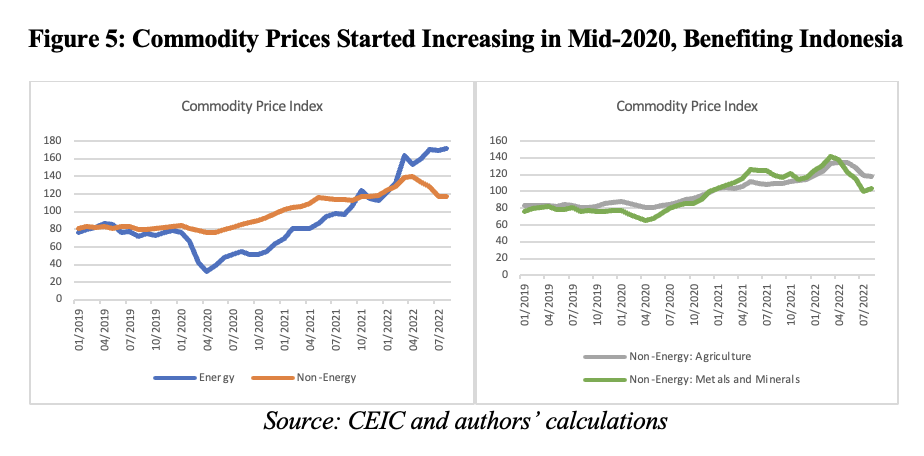

Given Indonesia’s relatively high projected economic growth and manageable inflation, its economy can be said to be doing quite well so far although a looming global economic recession next year and geopolitical uncertainties continue to pose a threat to the economy. The economic resilience so far could be partly attributed to the high commodity prices that have supported growth through higher export earnings, boosted fiscal revenues, and mitigated the social impacts of rising fuel and food prices through energy subsidies.

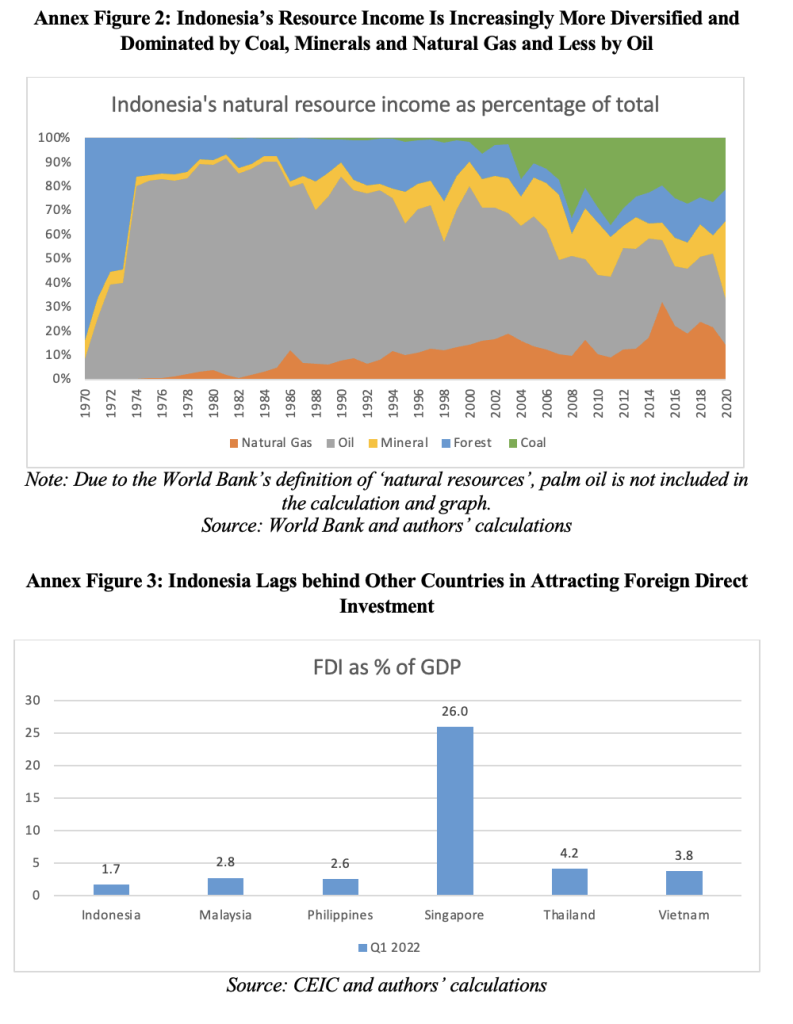

In short, Indonesia has benefited from the recent high commodity prices (Figure 5). According to the State of Commodity Dependence Report 2021 (UNCTAD, 2021), in 2018-2019, 55.6 percent of Indonesia’s merchandise exports were commodities.[2] The country has experienced two major commodity booms before: one dominated by oil in the 1970s and another by coal and palm oil in the 2000s, though the second commodity boom also featured more diversified sources of commodity income, including forest resources (such as timber), minerals, natural gas and oil (see Annex Figure 2; also see Hill and Pasaribu, 2022).

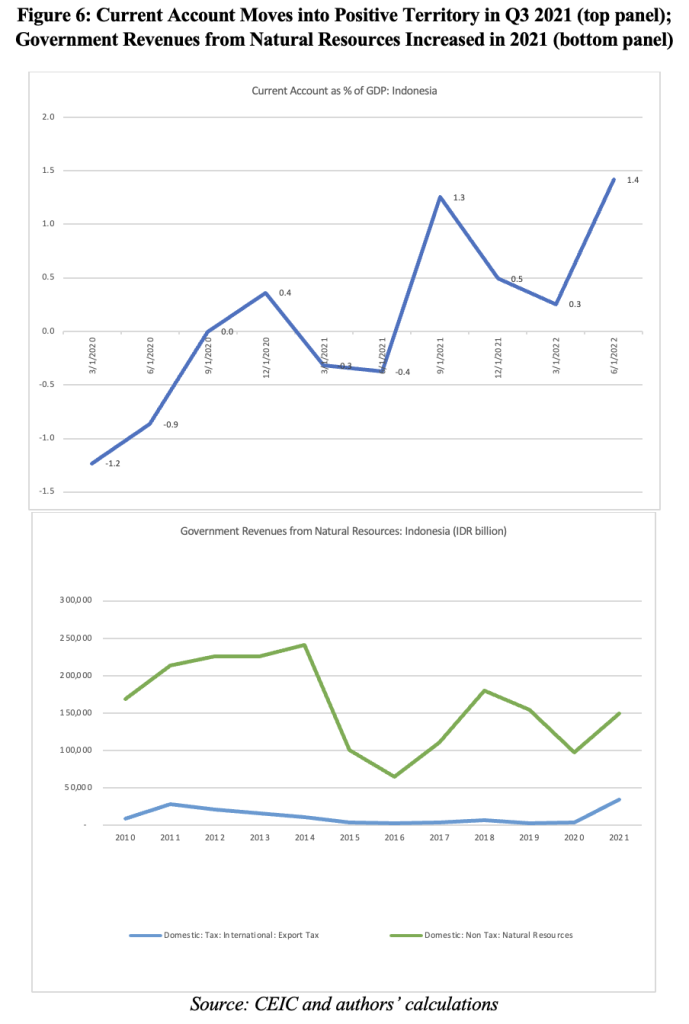

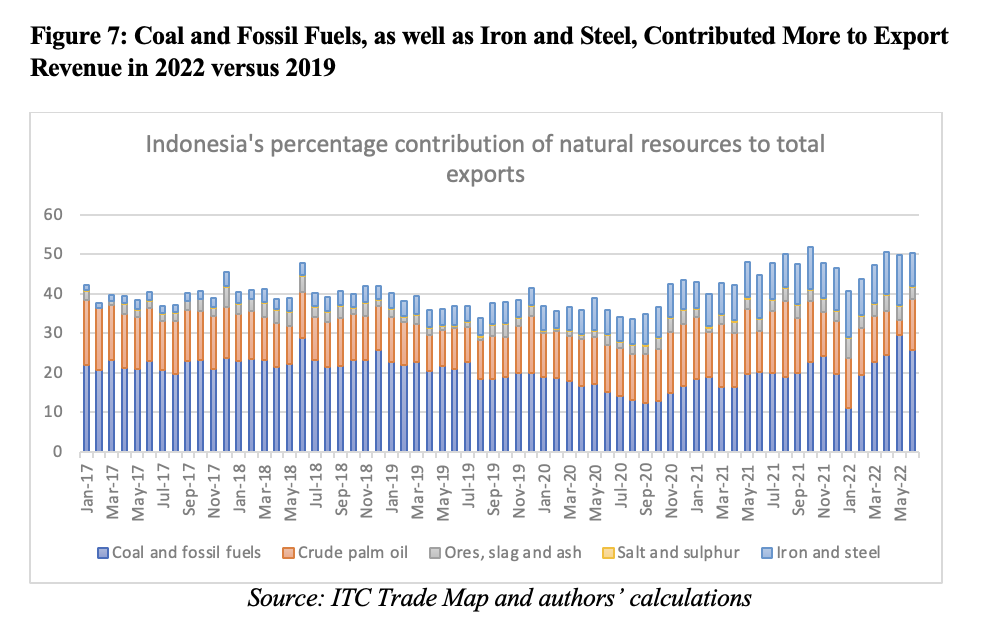

Due to the recent high commodity prices, Indonesia’s current account balance has flipped over into positive territory from a long-term deficit (Figure 6, top panel). Most of the additional export revenue reflects price increases rather than volume increases. Coal and fossil fuel contribution to total export revenue increased between four to five percentage points in June 2022 compared to June 2019 (Figure 7). While a current account deficit is not necessarily bad or good[3], it needs to be financed through net foreign financing (Ghosh & Ramakrishna, n.d.).[4] Having a current account surplus helps ease Indonesia’s balance of payment and stabilise the Rupiah.

The windfall from the commodity boom has also contributed to the government’s fiscal revenues. Both export taxes (the majority came from natural resource exports) and non-tax revenues on natural resources increased in 2021 (Figure 6, bottom panel). By June 2022, revenues collected from exports had reached IDR23 trillion (USD1.5 billion), making up 62.8 percent of the government’s full-year target (Ministry of Finance Indonesia, 2022a). The commodity windfall has helped the government reverse its high pandemic-level fiscal deficit and slowly begin returning to the pre-pandemic level of below 3 percent as mandated by the law. It is predicted that in 2022, the fiscal deficit will shrink to IDR868 trillion (USD56 billion) or 4.85 percent of GDP (Ministry of Finance, Indonesia, 2022b) from 6.14 percent in 2020 but slightly increase from 4.57 percent (unaudited) in 2021 (Ministry of Finance, Indonesia, 2022c).

POTENTIAL DOWNSIDES OF THE WINDFALL

Despite their short-term benefits, commodity booms are often associated with potential downsides, such as rising terms of trade and real effective exchange rate that adversely affect other non-booming tradables (the so-called ‘Dutch Disease’) and in turn may lead to protectionist policies on these non-booming tradables. In this section, we will discuss three potential long-term negative impacts from the current windfall, namely (1) uneven distributional consequences, (2) environmental effects, and (3) macroeconomic and fiscal instability. We will then discuss how Indonesia could manage them.

Uneven distributional consequences

In 2022, government fiscal expenditure is expected to increase by IDR357 trillion (USD23 billion) more than previously budgeted, largely due to an increase in subsidies, which are expected to reach 2.8 percent of GDP in 2022. This is the highest level of subsidies since President Jokowi took office in 2015 (Anas et al., forthcoming 2022).[5] The government had tripled the size of energy subsidies since Semester 2, 2021, when the state budget for 2022 was prepared, from IDR152.5 trillion (USD9.8 billion) to IDR502.4 trillion (USD32.4 billion) (President’s Secretariat, 2022).[6] This is expected to continue to increase to IDR653 trillion (USD42.1 billion) by the end of the year, even with the assumption that oil prices will go down from USD99 to USD90 per barrel until December, due to increased consumption of subsidised fuels than previously projected.

For successive governments, the fossil fuel subsidy has been a large part of the state budget. Nevertheless, the government stated that more than 70 percent of the current fuel subsidies have benefited the middle and upper classes (President’s Secretariat, 2022).[7] Poorly targeted energy subsidies could have been used for more pro-poor and pro-environment spending.

In early September, the government cut some fuel subsidies to reduce the fiscal burden. The IDR24.2 trillion of budget saved has been diverted to various targeted social assistance programmes including direct cash transfers to 20.65 million poor households, wage subsidy for 16 million workers, and social protection programmes delivered through local governments (President’s Secretariat, 2022). However, fuel subsidies are still very high and will increase.

Although diverting some fuel subsidies to targeted social assistance programmes is a welcome move, Indonesia’s social registry that is used to target the poor and vulnerable households – called the unified database or Data Terpadu Kesejahteraan Sosial (DTKS), which was first set up to support poor and vulnerable households when fuel subsidies were eliminated in 2005 – is still mired with many weaknesses, including challenges faced by local governments to update data and the quality of the data itself (World Bank and the Australian Government, 2022). This poses challenges in channelling commodity windfalls to the most needed households amidst rising fuel and food prices.

Environmental impacts

High coal prices and concerns over energy affordability and availability during the European winter encouraged Indonesian coal miners to increase production (Maulia et al., 2022). This might pose a risk to Indonesia’s energy transition target to cut coal-powered energy production from 60 percent to 45 percent by 2030. To make matters worse, in February 2021, the Indonesian government delisted coal waste from a list of hazardous waste (Siregar, 2021). This regulation is a derivative of the Omnibus Law on Job Creation, passed in 2020 to improve the investment climate and to create jobs.

Moreover, by using the windfall to subsidise fuel consumption that mostly benefits the middle and upper classes, Indonesia will have to face at least three dire consequences. First, subsidies encourage people to increase their consumption of fuels – they lack the incentive to conserve energy as subsidies hide the true cost of fuel (Li et al, 2017). Without blanket fuel price subsidies, relative price of fossil fuels to other renewable energies becomes more expensive, and Indonesia could use this momentum to accelerate its energy transition towards renewable energy instead (World Bank, 2022). Second, lower petrol prices have also contributed to more people purchasing private vehicles, which contributes to traffic congestion and pollution (Ardiansyah, 2012). And, third, subsidised fuel may act as a disincentive to energy producers to reduce production costs by adopting more efficient technology.

Macroeconomic and fiscal instability

Under an open capital account regime, commodity booms may not only lead to real exchange rate appreciation, affecting the term of trade and the performance of other tradeable sectors, but also crowd out the traded sector in terms of resource allocation, which may cause permanent de-industrialisation and a growth trap (Alberola and Benigno, 2017). Commodity-rich countries may suffer from currency depreciation during commodity busts and struggle to build back productivity and develop potential even during commodity booms.

Moreover, using most of the windfall from the commodity boom as fuel subsidies means the fiscal policy is pro-cyclical – more is spent during good times (booms) and less during bad times (busts). If commodity prices fall and income from the commodity windfall drops at a time when fuel subsidies are difficult to phase out politically, the government will soon run out of budget for other social assistance programmes, potentially resulting in lower economic growth due to muted demand. Moreover, even if other commodity prices fall, oil and gas prices are likely to remain high due to limited global supplies because of Russia’s gas sanctions and OPEC+ cutting oil production. Runaway inflationary expectations and labour shortages could also contribute to protracted high global inflation. Lower economic growth, combined with high global inflation, could trap Indonesia in a stagflationary spiral.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS: MANAGING THE WINDFALL FOR LONG-TERM BENEFITS

Although the Indonesian government has cut some fuel subsidies starting 3 September, public demand for them will continue, especially as revenues from the commodity boom are continuing to pour in and targeted social assistance programmes are constrained by weaknesses in the social registry data system. The main policy threat from the commodity windfall is that the government may lose sight of necessary long-term reforms, including climate change mitigation. A few policy recommendations follow:

Move away from the trap of reliance on commodities by attracting foreign direct investment towards a green economy

A significant shortcoming of Indonesia’s development model, which contrasts with other ASEAN five economies (Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines) is the relative lack of foreign direct investment (FDI) (see Annex Figure 3), particularly in the non-extractive, export-oriented manufacturing sector, to finance Indonesia’s structural current account deficit (during non-boom periods). A significant share of Indonesia’s FDI goes to extractive sectors, accounting for 41.2 percent of total FDI in 2021 (Figure 8).

FDI promotion could be focused on attracting green investment. Transition to a green economy and achieving the target of net-zero emissions by 2060, which Indonesia aspires to, will need a lot of financing – estimated at USD150-200 billion dollar per year until 2030 (IFG Progress, 2022).[8]

Indonesia has tried to move away from exporting raw commodities and to increase value addition by having downstreaming as one of its economic strategies. Export ban on nickel might soon be expanded to asphalt, tin, bauxite, and copper. However, the success of Indonesia’s current export ban on nickel ore – part of its downstreaming policy – is still debatable, notwithstanding that President Jokowi has already proclaimed it a success (Mariska, 2022; Gupta, 2022). Processing nickel apparently has also had detrimental impacts on the environment (Ruehl and Leahy, 2022). Hence, downstreaming minerals (alone) is unlikely to help solve economic and environmental problems in the long term.

Use a sovereign wealth fund to save and invest in windfalls

Windfalls from commodity booms could be saved for a rainy day and be used to meet the infrastructure, human capital and financial investment gaps in the long run through a sovereign wealth fund (SWF). Indonesia established a new SWF in February 2021, named the Indonesia Investment Authority (INA). But it is unconventional as it aims to attract domestic and foreign investment into the government’s infrastructure projects instead of using internal revenues to fund it. It is modelled more closely to India’s National Investment and Infrastructure Fund (Habir, 2021) than more traditional SWFs that are usually funded by commodity export revenues (or trade surpluses) or foreign-exchange reserves held by the central banks. Moreover, so far, INA has mostly been used to purchase assets, such as toll roads, from heavily indebted infrastructure-related state-owned enterprises (similar to privatisation of heavily-indebted government assets), instead of investing globally.

INA is in contrast with the Norwegian Oil Fund, where the source of funds comes from oil revenues that are invested for wealth creation, preservation of future generation, and supporting the government budget during a rainy day (Habir, 2021). In Chile, the Economic and Social Stabilization Fund was established to stabilise the economy during periods of volatility in copper prices (UNDP, 2015). When copper prices are high, a portion of the copper export revenues are directed to the fund and invested in low-risk assets. When copper prices are low, the accumulated resources are added to the government budget.

In the longer term, INA could be modelled more closely to the Norwegian Oil Fund or Chile’s Economic and Social Stabilization Fund to help Indonesia industrialise and move towards a greener economy, including by accelerating its investment and programme to use more efficient and cleaner coal-fired technology since coal will continue to account for a significant share of energy production in Indonesia.

However, there are challenges. Although it is theoretically possible to allocate commodity windfalls to SWF for investment, be this earmarked for green investment or not, most governments tend to use them to subsidise domestic fuel prices because it is more publicly popular. Moreover, as green investment might not be profitable at least in the short term, it might be contradictory to the goal of wealth creation, which makes it challenging for SWF authorities to put funds in green investment for fear of losing state money.

Improving data quality of the social registry to improve the targeting of social protection programmes

The windfall could be used to help poor and vulnerable households if social assistance could be properly targeted. The government has diverted some fuel subsidies to targeted social assistance programmes, which should be welcomed. However, Indonesia’s social registry to target poor and vulnerable households (DTKS) is still mired with many weaknesses (World Bank and the Australian Government, 2022). Therefore, reforms in the social registry of Indonesia’s DTKS will be critical to help distribute the commodity windfall to poor and vulnerable households that are disproportionately impacted by the high fuel and food prices.

REFERENCES

Alberola, Enrique and Gianluca Benigno. 2017. ‘Revisiting the Commodities Curse: A Financial Perspective.’ National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w23169

Anas, Titik, Hal Hill, Donny Narjoko and Chandra Putra. Forthcoming 2022. ‘The Indonesian economy in turbulent times.’ Presentation at the Australian National University Indonesia Update, September 18, 2022.

Ardiansyah, Fitrian. 2012. ‘Bearing the consequences of Indonesia’s fuel subsidy.’ East Asia Forum. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2012/05/04/26135/

Asian Development Bank. 2022. ‘Asian Development Outlook. Economic Forecasts.’ https://www.adb.org/outlook

Bank Indonesia. N.d. ‘Inflation target.’ https://www.bi.go.id/en/statistik/indikator/target-inflasi.aspx

BKPM. (2022, April). BKPM. Retrieved from FDI realization: https://www.bkpm.go.id/id/statistik/investasi-langsung-luar-negeri-fdi

Borsuk, Richard. 2022. ‘Surprise court ruling: Jokowi’s Omnibus Law hits snag.’ RSIS: S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. https://www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/rsis/surprise-court-ruling-jokowis-omnibus-law-hits-snag/#.YvW2rHZBy5c

Calderón, César, Alberto Chong and Norman Loayza. 2000. ‘Determinants of current account deficits in developing countries.’World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. World Bank, Washington, D.C.. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/19825/multi_page.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

CNBC. 2022. ‘Smooth Revenues, Fiscal Deficit 2022 Is Predicted to Decline to 3.9% of GDP’. https://www.cnbcindonesia.com/news/20220701102353-4-352049/setoran-lancar-defisit-apbn-2022-diramal-turun-ke-39-pdb

Dartanto, Teguh. 2013. ‘Reducing fuel subsidies and the implication on fiscal balance and poverty in Indonesia. A simulation analysis.’ Energy Policy 58: 117–134, July. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.02.040

ECB (European Central Bank). N.d. ‘Key ECB interest rates’. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/policy_and_exchange_rates/key_ecb_interest_rates/html/index.en.html

Federal Reserve. N.d. ‘Policy tools: open market operations’. https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/openmarket.htm

FRED Economic Data, n.d. ‘Federal funds effective rate’. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FEDFUNDS

Ghosh, A., & Ramakrishna, U. (n.d.). ‘Current Account Deficits: Is There a Problem?’ IMF. Retrieved from Current Account Deficits: Current Account Deficits: Is There a Problem? (imf.org)

Granado, Javier Arze del, David Coady and Robert Gillingham. 2010. ‘The unequal benefits of fuel subsidies: A review of evidence for developing economies.’IMF Working Paper. Microsoft Word – DMSDR1S-4157337-v14-Working Paper–The Unequal Benefits of Fuel Subsidies_ A Review of Evidence for Developing (imf.org)

Gupta, Krisna. 2022. ‘Indonesia’s claim that banning nickel exports spurs downstreaming is questionable.’ The Conversation, March 30. https://theconversation.com/indonesias-claim-that-banning-nickel-exports-spurs-downstreaming-is-questionable-180229

Habir, Manggi Taruna. 2021. ‘Indonesia’s First Sovereign Wealth Fund (INA): Opportunities and Challenges.’ ISEAS Perspective. /articles-commentaries/iseas-perspective/2021-63-indonesias-first-sovereign-wealth-fund-ina-opportunities-and-challenges-by-manggi-taruna-habir/

Hill, Hal and Donny Pasaribu. 2022. ‘Some reflections on Indonesia and the resource curse.’ Australian National University’s Australian Council of Dean of Education seminar presentation, 12 April.

IFG Progress. 2022. ‘Energy transition and financial sector in Indonesia.’ https://ifgprogress.id/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Econ.-Bulletin-Issue-4-Green-Economy_24-Jan-2022-F.pdf

Li, Yingzhu, Xunpeng Shi and Bin Su. 2017. ‘Economic, social and environmental impacts of fuel subsidies: A revisit of Malaysia.’ Energy Policy, 110, 51–61.

Liputan6. (2022, August 24). Liputan6. Retrieved from ‘The Government Predicted Inflation 2022 Maximal 4.8%’ (Pemerintah Proyeksi Inflasi 2022 Maksimal 4.8%). https://www.liputan6.com/bisnis/read/5050725/pemerintah-proyeksi-inflasi-2022-maksimal-48-persen-masih-aman

Mariska, Diana. 2022. ‘Nickel export ban has benefited Indonesia: Jokowi.’ TheIndonesia.id, 3 January.

Maulia, Erwida, Nana Shibata and Ismi Damayanti. 2022. ‘Indonesian coal miners pump up production, eye European winter’. Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Energy/Indonesian-coal-miners-pump-up-production-eye-European-winter

Ministry of Finance Indonesia. 2022a. State Budget Realization per 30 June 2022. https://djpb.kemenkeu.go.id/portal/id/berita/lainnya/pengumuman/153-apbn/3944-realisasi-apbn-per-30-juni-2022.html

Ministry of Finance Indonesia. 2022b. Budget Monthly Press Release. September 2022. https://youtu.be/IAdzdGUpo1g

Ministry of Finance Indonesia. 2022c. ‘Macro Economic Framework and Fiscal Policies, 2023’. https://fiskal.kemenkeu.go.id/informasi-publik/apbn?tahun=2023

Moody’s Investor Service. (2022). Global Macro Outlook 2022-23 (August 2022 Update). New York: Moody’s. https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-cuts-global-economic-growth-forecasts-as-financial-conditions-tighten–PBC_1340740#:~:text=Moody’s%20Investors%20Service%20has%20reduced,to%202.1%25%20from%202.9%25

President’s Secretariat. 2022. Press Conference by President Jokowi and related Ministers on fuel subsidy diversion. https://youtu.be/gsL6-YtDObA

Ruehl, Mercedes and Joe Leahy. 2022. ‘Indonesia’s unexpected success story.’ Financial Times. September 22, 2022. https://www.ft.com/content/f179df5b-1dc7-46f4-88dc-97ddfe1d2fe4

Siregar, Kiki. 2021. ‘Declassifying coal power plant ash as hazardous waste sparks concern in Indonesia,’ 22 April, Channel News Asia.

UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development). 2021. State of Commodity Dependence 2021.Geneva: UNCTAD. https://unctad.org/topic/commodities/state-of-commodity-dependence

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2015. Towards Human Resilience: Sustaining MDG Progress in an Age of Economic Uncertainty. New York: UNDP.

Vos, Rob. 2022. ‘What the G20 can do to address the global food crisis.’ Slide presentation at the USINDO-IFPRI webinar on the global food security agenda at the G20. 9 September.

World Bank. 2022. ‘Reforms for Recovery: East Asia and Pacific Economic Update, October 2022’ https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/east-asia-and-pacific-economic-update#3

World Bank and the Australian Government. 2022. ‘Improving Data Quality for an Effective Social Registry in Indonesia.’ The World Bank publication, Washington, D.C.. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/38157

ANNEX

Source: This article was published by ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute

ENDNOTES

[1] For example, by mid-September 2022, the US Federal Reserve had already increased its Federal Open Market Committee’s target Fed Funds Rate by 200 basis points this year to 2.25–2.5 percent (Federal Reserve, n.d.) and is expected to increase it again for the fifth time this year. The actual Fed Funds rate has increased six times this year, reaching 2.33 percent by August 2022 (FRED Economic Data, n.d.). Likewise the European Central Bank has also increased its interest rate to combat rapidly rising inflation resulting from the phasing-out of Russian gas and oil (ECB, n.d.).

[2] Meanwhile, Indonesia’s regional peers such as Vietnam, India and the Philippines depend less on commodity exports, which comprise only 14.6, 37.4 and 18.5 percent, respectively, of their merchandise exports.

[3] A higher domestic output growth rate is found to have a positive effect on the current account deficit in 44 developing countries studied between 1966 and 1995 in Calderón et al. (2000).

[4] Foreign financing could come, among others, in the form of portfolio investment and foreign direct investment (FDI).

[5] For successive governments, the fossil fuel subsidy has been a large part of the state budget. In 2013, during the Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono administration, it was as much as 3-4 percent of GDP (Anas et al., forthcoming 2022). The Jokowi administration initially eliminated the subsidy, but slowly reintroduced it in 2017, albeit via compensation channelled through state-owned enterprises.

[6] Most of the energy subsidy increase comes from the increase in compensation (off-the-book subsidies channelled through state-owned enterprises, mostly oil and natural gas enterprise, Pertamina) instead of direct subsidy. Compensation is projected to increase from IDR93.1 trillion in 2021 to IDR293.5 trillion in 2022, while the energy subsidy is expected to increase from IDR140.4 trillion in 2021 to IDR208.9 trillion in 2022 (President’s Secretariat, 2022; Anas et al., forthcoming 2022, based on Presidential Regulation No.98/2022 on revised budget).

[7] Granado et al. (2010) found that globally subsidies benefit the wealthiest 20 percent of the population who disproportionately enjoy 43 percent of the benefits, while the poorest 20 percent only enjoy 7 percent of the benefits. In Indonesia, 72 percent of the fuel subsidy was enjoyed by the top 30 percent of income earners between 1998 and 2013, and it accounted for 63.8 percent of all subsidies over that period (Dartanto, 2013).

[8] To promote FDI, Indonesia needs to invest more in basic infrastructures such as electricity, roads, and ports to access areas where investment is targeted. Also, it needs to provide regulatory certainty for investors. The controversy surrounding the Job Creation Law remains unresolved after the Constitutional Court’s decision to ask the government to revise it within two years (Borsuk, 2022). However, the real problem is that hundreds of local regulations are still not aligned with national regulations.