Kazakh Leadership Now Appears To Be Eager To Make Putin’s Vision Of Kazakhstan Come True – OpEd

In Ukraine, military activities which started exactly one week ago have been continuing so far. And there is no end in sight. Therefore, it seems that, one way or another, the Kazakh public will have a need to consider this course of events to be a signal of looming challenges to the independence of Kazakhstan in adopting internal and foreign policies and an upcoming testing of the political will of their leaders.

In his article titled “Moscow has turned the Russian language into an excuse for annexation and occupation”, and published by Liga.net, Pavel Kazarin, a Ukrainian journalist said: “The countries neighboring the Russian Federation have to defend themselves not so much from the very Russian language, but from everything that is attached to it. In the fall of 2019, Russian President Vladimir Putin spoke about the attempts to ‘blatantly reduce the Russian language [and culture] space in the world’. He put the blame on the ‘primeval nationalists’ and the governmental policy of individual countries. Well, that’s where one has to agree with the Russian president. The Kremlin policy indeed does not serve the cause of the Russian language. Unlike English, the Russian language is deprived by Moscow of a main prerequisite [for continued functioning as an international language], its political neutrality.

Learning English does not mean encroaching upon the [national] identity [of the country concerned] – a Lithuanian who has learned to speak English continues being a Lithuanian, and a Kazakh continues being a Kazakh. Whereas the Russian language [has been and] is being sold by the Kremlin in a package with loyalty to the empire and acceptance of the Russian version of history. Moscow has made every effort to turn ‘Russian schools’ abroad into factories to create [separate] communities of ‘Russian people’. Those, who should be in opposition to their own country, its history and [State] language, are meant here. That [has been and] is being done just for using them subsequently as leverage, as an instrument for influencing and as a pretext for interference [in the domestic affairs of another State]”.

All of the above seems no longer to be simply an assumption. Obviously, it now should appear to be something that has been tested in real life and confirmed for all to see in the case of Ukraine. It is unlikely that someone outside of the Russian Federation and Russian communities abroad can challenge this simple, indisputable fact.

What is the situation in Kazakhstan in that regard? Here is the way Sergey Duvanov, a Kazakhstani freelance journalist and human rights activist of Russian origin, see it: “In Europe, many countries have put bans on the main Russian propaganda outlets. European politicians have now become aware of their negative role in shaping anti-Western and pro-Russian attitudes, i.e. attitudes that are contrary to the liberal values of the Western world. Largely because of this, immigrants, originated from the countries of the former USSR, are overwhelmingly in support of Putin and his policies of diktat toward neighboring countries. But it was the countries of the former Soviet Union that, first and foremost, faced this challenge…

In Kazakhstan, which is completely involved in the information space of Russia, this has given rise to a situation where about half of the population think in terms of Putin’s imperial revanchism, maintain a radical anti-Western position, fear NATO, despise liberal values and are critical of democracy. That is why, more than 70% of Kazakhstanis supported the annexation of Crimea [by Russia] in 2014, and about half of them approve of Putin’s aggression in territories of Ukraine nowadays. In view of what happened earlier in Georgia, then in Crimea and what is now happening in Ukraine, the situation seems quite alarming. In the country, half of the population consists of the [so-called] ‘vatniks’ [Russian jingoists and supporter of Putin’s politics], who do not take themselves seriously as citizens of Kazakhstan, who hate America and Europe for their liberal attitude towards sexual minorities, and for a situation where the United States ‘dictate to everyone how they should live’, and, as a result, see in Putin’s Russia the [only] salvation from the imposition of democracy and liberal values. This means, should Putin wish to annex Kazakhstan tomorrow, those people will respond enthusiastically to this.

After the Euromaidan, Ukraine had faced such a challenge, and therefore all Russian TV channels were removed there. This proved to be the only possible way to block Putin’s propaganda and improve the media environment in the country.

The same should be done in Kazakhstan. I do believe that the removal from the Kazakh information space of Russian propaganda and politically biased media content is the most important task before the country’s national security system. It must be done without delay, i.e. the sooner the better…

Unfortunately, the authorities of Kazakhstan cannot go through with this because of their having been heavily dependent on the Kremlin, and they therefore cannot count on the support of the country’s entire population in the event of a conflict with Putin. In order to become informationally independent, the country need to remove Russian TV channels, but this cannot be done for reasons of its great dependence [on Moscow]…

I am afraid that this vicious circle would not be broken under the current power in Kazakhstan”.

Shutting down (or refraining from) the broadcasting of Russian TV channels (as well as the other Russian media outlets) actually seems to be not sufficient, or even not quite fit, for fully addressing information security problems in the country. Such a decision, if adopted in a straightforward way, would be met with anger and annoyance from people. In an age of globalization, it generally makes little sense to shut down foreign TV channels. In the case of Kazakhstan, it seems far more reasonable to follow in Armenia’s footsteps. There are two reasons for this. First, that nation is a post-Soviet country which, just like Kazakhstan itself, is part of the CSTO and the EEU. Second, Armenia also very much depends on Russia now.

On August 5, 2020, the Republic of Armenia adopted the law ‘About audiovisual media’, the purpose of which is, among other things, to regulate the broadcasting in foreign languages, including Russian, but only in public multiplex. How that requirement should be implemented? The law states: “The audiovisual information broadcast in foreign languages shall be followed by means of perception in Armenian (to dubbing-ins, post-scoring and (or) subtitlings). Maintenance by means of perception in Armenian shall be applied only to audiovisual information in original language”. According to official Erevan, it does not provide for a ban on the broadcasting of Russian TV companies in Armenia and leaves both states the door open – to conclude intergovernmental agreements to ensure broadcasting of Russian channels through the Armenian public multiplex. They add that there is no talk about shutting down hundreds of foreign broadcasters that are available on cable networks, satellite TVs, it is just about a public multiplex. The objective is, in their words, how best to broadcast programs in the State language, to promote a state agenda, preserve the national identity, language and culture in the free public multiplex. Tigran Hakobyan, chairman of the Commission on TV and radio of Armenia, said that the adoption of this law had been dictated by the need to ensure both ‘information’ and ‘language security’. According to the above, information security is inextricably linked with language security. Anyway, this seems to be the case in former Soviet States outside Russia.

Pavel Kazarin, the author of the above mentioned article in Liga.net, gave the following advice: “Do you want to protect yourself from intrusion [by Russia]? If so, you should strive to ensure the monolithic unity [among the people of all ethnic groups in the country], [their] linguistic homogeneity, positive discrimination and [their] unified and sovereign vision of the country’s history”.

Kazakhstan has got big problems with ensuring linguistic homogeneity, particularly as the country is headed by the President who has given the impression of being not fluent in Kazakh and not able to freely carry on a conversation, while using the State language. He mainly uses Russian while doing the public speaking. That’s understandable, given his professional life experience and educational background. His first working language has been and is the State language of the Russian Federation. It may be supposed that for him, the need to deliver a speech in Kazakh is a kind of stepping outside of his comfort zone. That’s why his working meetings are likely being held in Russian nowadays. Anyway, public speeches and TV interviews by the Kazakh cabinet ministers (and other high-level officials) and MPs in Russian have become increasingly frequent.

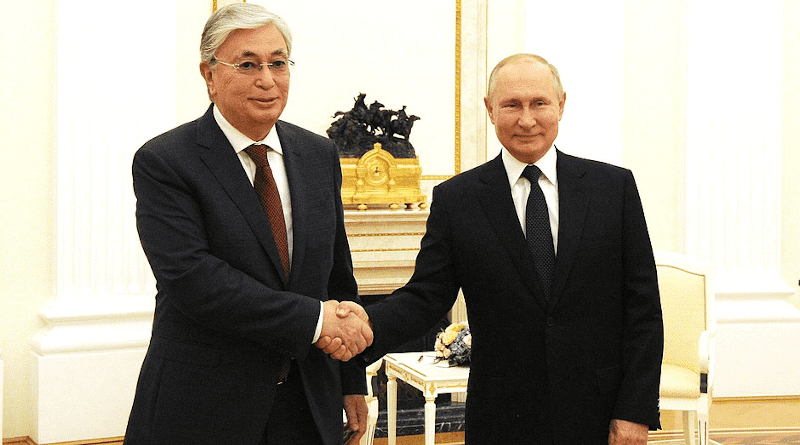

Russian President Vladimir Putin apparently took into account such a factor, while seeing Kazakhstan as ‘a Russophone State in the full sense of the word’.

Some of MPs from his ruling party go even further. Thus, Biisultan Khamzaev, a member of the State Duma Committee on security and anti-corruption, spoke in favor of holding a referendum on ‘the reunification of Kazakhstan with the historical homeland – Russia’. “Central Asia is Russian land! There are discussions on the internet about the possible reunification of Kazakhstan with Russia […] I support the holding of a referendum in Kazakhstan on reunification with its historical homeland – Russia”, – he wrote in his Facebook account. Mr.Khamzaev added that Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev deliver his statements in Russian, which, in his opinion, ‘may be taken as an indicator that this [Kazakhstan] is [originally] Russian land’.

The Russian authors seem to be glad to say that Mr.Tokayev has decided to ‘freeze this transition [to the Latin alphabet] and leave everything as it is’, given that ‘the language issue is increasingly being raised by Russia’.

Under these circumstances, one is left with the impression that the Kazakh leadership is eager to make Putin’s vision of Kazakhstan come true.

*Akhas Tazhutov is a political analyst.