36 Years Since Battle Of The Beanfield The Tories Remain Committed To Eradicating Nomadic Way Of Life – OpEd

36 years ago, on June 1, 1985, Margaret Thatcher’s para-militarised police force, fresh from suppressing striking miners, turned their attention, via what has become known as the Battle of the Beanfield, to the next “enemy within” — the travellers, environmental activists, festival-goers and anarchists who had been taking to the roads in increasing numbers in response to the devastation of the economy in Thatcher’s early years in office.

The unemployment rate when Thatcher took office, in May 1979, was 5.3%, but it then rose at an alarming rate, reaching 10% in the summer of 1981 and hitting a peak of 11.9% in the spring of 1984. Faced with ever diminishing work opportunities, thousands of people took to the roads in old coaches, vans and even former military vehicles.

Some, inspired by the Women’s Peace Camp at Greenham Common in Berkshire, which was undertaken to resist the establishment of Britain’s first US-controlled cruise missile base, engaged in environmental activism, of which the most prominent example was the Rainbow Village established in 1984 at RAF Molesworth in Cambridgeshire, intended to be Britain’s second cruise missile base, while others found an already established seasonal free festival circuit that ran though the summer months, and whose focal point was the annual free festival at Stonehenge, first established to mark the summer solstice at Britain’s most celebrated ancient monument in 1974, which had been growing ever larger, year on year, drawing in tens of thousands of visitors, myself included, in 1983 and 1984.

In February 1985, as the Miners’ Strike was reaching its end, the Rainbow Village was evicted by the largest ever peacetime mobilisation of troops in the UK (1,500 troops, symbolically led by the defense secretary Michael Heseltine), and from then on those who took to the road, trying to bide their time until they set off for Stonehenge to establish what would have been the 12th annual free festival, were consistently harried and kept under surveillance by the police.

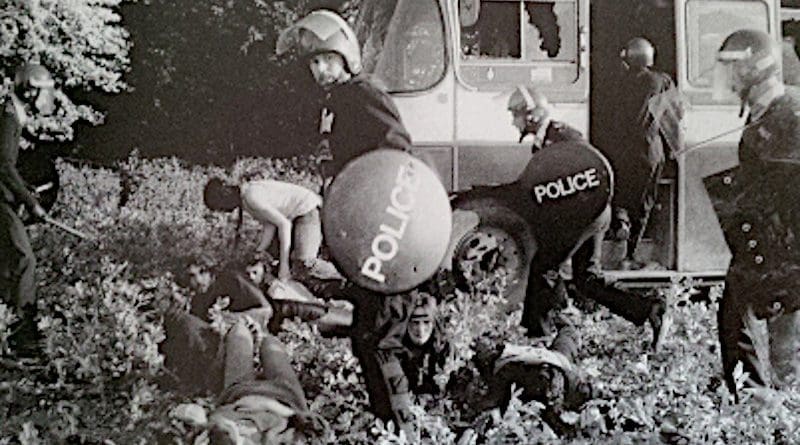

On June 1, after gathering in Savernake Forest, near the Wiltshire border, a convoy of vehicles, containing over 400 men, women and children, set off for Stonehenge, but soon hit a police road block and found themselves subjected to an unprecedented display of violence, as 1,400 police from six counties and the MoD started trashing people’s vehicles and arresting them.

In response, some of the convoy sought refuge in fields beside the road, including the beanfield that gave the day its name, although the notion that this was any kind of ‘battle’ is a misnomer as, after an impasse that lasted throughout the afternoon, the day ended in a one-sided assault of astonishing brutality by the police, with numerous unarmed individuals subjected to extraordinary physical violence, their vehicles destroyed, and some set on fire, and with the police swarming like a homicidal conquering army over the last few vehicles to resist arrest. By the end of the day, everyone had been arrested and, with families deliberately split up, taken to police stations across the south east.

The trauma of that day, for those subjected to this unprecedented display of the force of the state, was profound, and yet no one has ever been held accountable for so demonstrably crossing a line that should never be crossed in societies that claim to respect the rule of law.

Ironically, Thatcher’s efforts to wipe out the New Age Traveller movement, and to stamp out dissent, backfired spectacularly when a brand-new free party movement, based on rave music and the arrival in the UK of ecstasy (MDMA) spectacularly revived the spirit of the free festivals, and when environmental campaigners, prevented from travelling freely, instead rooted themselves to the land, setting up camps — and tunnels, and tree houses — to resist road expansion schemes with the kind of mystical reverence for the land that was a clear continuation of many of the impulses behind the free festival movement.

Nevertheless, in terms of our freedoms — for example, the assertion of a claimed right to gather freely in significant numbers without prior permission, which had often been tolerated by the authorities — the Beanfield marked a noticeably authoritarian shift in the politics of dissent.

As I explained in an article for the Guardian on the 24th anniversary of the Battle of the Beanfield, in 2009, the Public Order Act of 1986, passed as a follow-up to the Beanfield, “enabled the police to evict two or more people for trespass, providing that ‘reasonable steps have been taken by or on behalf of the occupier to ask them to leave.’ The act also stipulated that six days’ written notice had to be given to the police before most public processions, and allowed the police to impose unspecified ‘conditions’ if they feared that a procession ‘may result in serious public disorder, serious damage to property or serious disruption to the life of the community.’”

Eight years later, in 1994, even more draconian restrictions on our right to gather freely were imposed in the Criminal Justice Act of 1994, which arose in response to what ended up being the UK’s last great free festival — at Castlemorton Common in Gloucestershire, when, over the Bank Holiday weekend in 1992, tens of thousands of people, representing all the various tribes of the 1990s counter-culture, gathered in an extraordinary demonstration of resistance to what, by then, was 15 years of Tory rule.

As I also explained in my Guardian article in 2009, the Criminal Justice Act “amended the Public Order Act by introducing the concept of ‘trespassory assembly’”, which Thatcher had tried, unsuccessfully, to use to prosecute the brutalised survivors of the Beanfield.

“This”, I proceeded to explain, “enabled the police to ban groups of 20 or more people meeting in a particular area if they feared ‘serious disruption to the life of the community’, even if the meeting was non-obstructive and non-violent.” The Act “also introduced ‘aggravated trespass’, which finally transformed trespass from a civil to a criminal concern.”

The Public Order Act of 1986 and the Criminal Justice Act of 1994 had a devastating effect on mass celebratory dissent, but it was not only partying that was targeted. Disturbingly, in an ongoing demonstration of an urge to outlaw Britain’s travelling communities — whether traditional Gypsies or the newer Travellers — the Act also repealed the 1968 Caravans Sites Act, potentially criminalising the entire way of life of gypsies and travellers by removing the obligation on local authorities to provide sites for them.

Priti Patel and the latest attack on Britain’s travelling communities

Fast forward 27 years, and another Tory government, led by Boris Johnson, and with the notoriously bigoted Priti Patel as home secretary, has launched a new assault on Gypsies and Travellers — and on our right to protest — via the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill 2021.

I have written recently about Patel’s pernicious attempts to stifle non-violent protest, inspired by her hostility towards Extinction Rebellion and the Black Lives Matter movement, but on the anniversary of the Beanfield it is hugely important for people to understand quite how punitive Patel’s proposals are with regard to Britain’s nomadic communities.

As I explained in November 2019, in “First They Came for the Travellers”: Priti Patel’s Chilling Attack on Britain’s Travelling Communities — which remains my most read and shared article, liked and shared over 30,000 times on Facebook — Priti Patel “launched a horrible attack on Britain’s travelling community, suggesting that the police should be able to immediately confiscate the vehicle of ‘anyone whom they suspect to be trespassing on land with the purpose of residing on it’, and announcing her intention to ‘test the appetite to go further’ than any previous proposals for dealing with Gypsies and Travellers.”

In my article, I quoted the Guardian’s columnist George Monbiot, who explained that, “Until successive Conservative governments began working on it, trespass was a civil and trivial matter. Now it is treated as a crime so serious that on mere suspicion you can lose your home.” As he added, “The government’s proposal, criminalising the use of any place without planning permission for Roma and Travellers to stop, would extinguish the travelling life.”

I also noted how George Monbiot had explained that the result of “the Conservative purge in the late 1980s and early 1990s” was that “two thirds of traditional, informal stopping sites for travellers, some of which had been in use for thousands of years, were sealed off”, sowing the seeds of today’s crisis. As Monbiot also explained, consultation in 2019 “acknowledge[d] that there [was] nowhere else for these communities to go, other than the council house waiting list, which means abandoning the key elements of their culture.” As I added, “No wonder he concluded that Priti Patel’s proposal ‘amounts to legislative cleansing.’”

As I also explained in November 2019, despite Priti Patel’s hostility, it was noticeable that the police were ”overwhelmingly opposed to the plans.” As I noted, “Submissions from the police, for a consultation launched [in 2018], which were obtained by Friends, Families and Travellers under freedom of information legislation, ‘showed’, as the Guardian described it, ‘that 75% of police responses indicated that their current powers were sufficient and/or proportionate. Additionally, 84% did not support the criminalisation of unauthorised encampments and 65% said lack of site provision was the real problem.’”

Undeterred, however, Priti Patel’s new police bill reinforces her callously destructive and bigoted assault on the nomadic way of life, as Luke Smith, a Romani Gypsy engineering worker, explained in an article for Tribune in March.

As he stated, “The truth is that the trespass provisions in the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts (PCSC) Bill were never about solving unauthorised encampments. They are about using our pariah status as a community to embolden the racist underbelly of this country, and rally citizens around another culture war enemy that mostly exists in their minds. For the 15-20 percent of Gypsy and Traveller people who still live the historic and nomadic way of life, as our ancestors did, the PCSC Bill is a matter of survival, both physically and culturally. This bill seeks to make our people criminal just for having the audacity to exist.”

Luke Smith added that the provisions of the bill “can only be described as legitimising twenty-first century pogroms against Gypsies and Travellers”, given that they allow for “[f]ines of up to £2500 and three-month prison sentences for unauthorised encampments”, “[t]he seizure of vehicles and trailers at the discretion of police, held until the conclusion of criminal proceedings (which could mean months and months without a home)”, and “[t]he sale of vehicles and trailers to pay fines.”

As he also noted, “Even worse consequences are implied: for example, parents who are put in prison and who have their homes removed will face the real threat of children’s services removing their children and placing them into care — a habit the British state has had for a long time regarding Gypsy and Traveller children.”

On the 36th anniversary of the Battle of the Beanfield, when travellers’ homes were destroyed and their children taken into care, this latest assault on the lives of Britain’s nomadic people — whether Gypsies, Roma or Travellers — needs to be resisted as widely as possible. A famous quote attributed to Mahatma Gandhi states that “the true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members”, and yet, for Priti Patel and those who support her, the entire way of life of some of Britain’s most vulnerable people needs to be eradicated because of its perceived threat to those who are better off — and that way, as I hinted at when I wrote “First they came for the travellers” in November 2019, paraphrasing Pastor Niemöller in his observations about the Nazis in the 1930s, lies an authoritarian menace that is a threat to us all.

For detailed accounts of the Beanfield and the wider free festival and travellers’ movements, my books The Battle of the Beanfield and Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion are both still in print, and can be ordered from me by clicking on the links.