The Practical Symbolism Of Sanctions On Iran’s Supreme Leader – OpEd

By Hamid Enayat

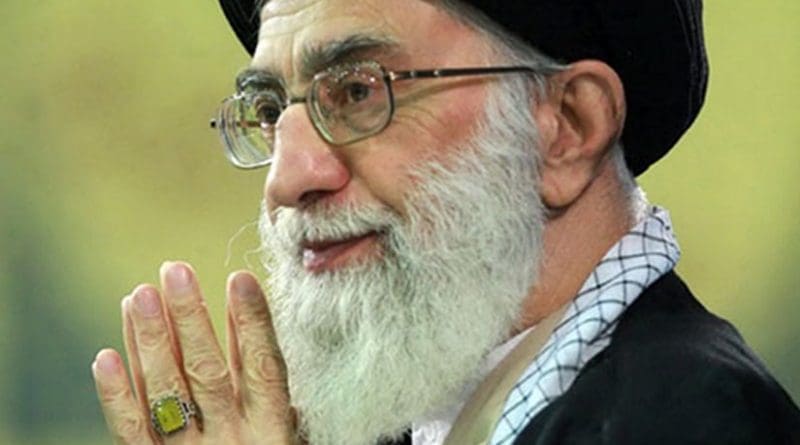

Ever since US President Donald Trump imposed sanctions on Iran’s supreme leader last week, there has been some debate about what, if any practical effect the measures would have. Some outlets described them as purely symbolic, while others noted that Ali Khamenei stands at the head of a 200 billion dollar financial empire, which cannot possibly function in complete isolation from American businesses and financial institutions

In detailing the sanctions to the press last Monday, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin stated that they would “lock up literally billions of dollars more of assets.” He also specifically rejected the notion that their symbolism exceeds their substance, as well as the notion that they would have no impact on prospects for negotiation in the wake of Khamenei’s insistence that the Iranian regime is unwilling to talk to the US.

That defiance is certainly nothing new. Even after giving his tacit approval for the 2015 nuclear deal, the supreme leader continued to speak out against the diplomacy that underlay them. Within months of its signing, he said in a speech, “Our problems with America… are not solved through negotiations. Addressing a variety of regime officials and supporters on August 1, 2016, he said, “You should know that it is not possible to negotiate with this enemy. The reason why I have been repeating for many years that we will not negotiate with America is this.”

Of course, the nuclear deal showed that negotiations are technically possible. More to the point, it showed that serious economic pressure can indeed force the regime to the negotiating table. But Khamenei’s subsequent comments support President Trump’s decision to pull out of that agreement.

The supreme leader’s apparent disavowal of the nuclear deal is particularly alarming when one considers the weaknesses cited by the White House in pulling out last year. It placed no limits on Tehran’s nuclear program and did nothing to address its imperial aspirations in the region. Neither did it provide any long-term guarantee of Iranian compliance with the restrictions on its nuclear enrichment. The regime already violated stockpile limits put in place by the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, within weeks of demanding that the European Union help to mitigate the effects of US sanctions.

Fortunately, the EU took no such action. Yet its leadership apparently remains unconvinced of the need to put additional pressure on Tehran over nuclear development as well as other issues. Or perhaps the Europeans are being held back by doubts over the practical effects of a still-expanding list of sanctions. If this is the case, the regime’s latest actions should be reason enough to abandon those doubts.

In fact, many of Iran’s recent protests have entailed much broader statements of opposition to the existing government than had been familiar for most of the regime’s 40-year history. Like the latest US sanctions, the protesters have taken specific aim at Supreme Leader Khamenei, in the form of slogans like “death to the dictator.” In this context, it bears mentioning that while the sanctions will probably continue to cut off more and more of Iran’s access to foreign capital, their oft-dismissed symbolic effects are actually practical in their own right. They help to motivate even more anti-government sentiment inside the Islamic Republic while giving the activist community reason to believe they have support among the international community.

Notably, the leaders of Iran’s democratic opposition movement share this perception of the sanctions’ dual purpose. Maryam Rajavi, the leader of the National Council of Resistance of Iran, was quick to issue a statement praising the Trump administration’s targeting of Khamenei and a number of officers in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. She described those measures as “spot on and most imperative,” in light of the central role played by the supreme leader’s office in the proliferation of both domestic corruption and international terrorism.

Rajavi went on to urge the US and its allies to extend financial pressure to the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence and Security, as well. In so doing, she said, the democratic nations of the world would go a long way toward conclusively undermining the regime’s efforts at blocking “the uprising for a Free Iran.” The world saw a hint of that uprising at the beginning of 2018, when the call for “death to the dictator” spread across more than 100 Iranian cities and towns. The subsequent violent repression of that movement underscored the fact that Tehran is no more interested in negotiating with its own people than it is in negotiating with the US.

In the face of such defiant resistance to change, Western policymakers should set their sights on something higher than negotiations. Symbolically, sanctions on the supreme leader may show that the US is doing just that. The previous presidential administration reportedly declined to impose those same sanctions out of fear of lending credence to Tehran’s allegations that the US was pursuing regime change. The Trump administration, it seems, is unconcerned with those allegations. And perhaps part of the reason for this is because it appears increasingly likely that regime change will actually be achieved in Iran, without direct intervention from outside its borders.

*Hamid Enayat is an Iranian human rights activist and analyst based in Europe.