The Good, The Bad And The Ugly About The Iran Deal – OpEd

How the deal will be implemented, whether or not Iran ultimately acquires nuclear weapons in five or ten years, and how the US in particular will act throughout the implementation process will determine if the deal is successful or not, and whether it passes the threshold of being historic.

By Dr. Alon Ben-Meir*

The deal with Iran has been generally characterized as either good or bad, and many pronounced it as historic with far-reaching regional and even global implications. I completely disagree with the characterizations of the deal as entirely good or bad, and certainly it is not historic as of yet. How the deal will be implemented, whether or not Iran ultimately acquires nuclear weapons in five or ten years, and how the US in particular will act throughout the implementation process will determine if the deal is successful or not, and whether it passes the threshold of being historic.

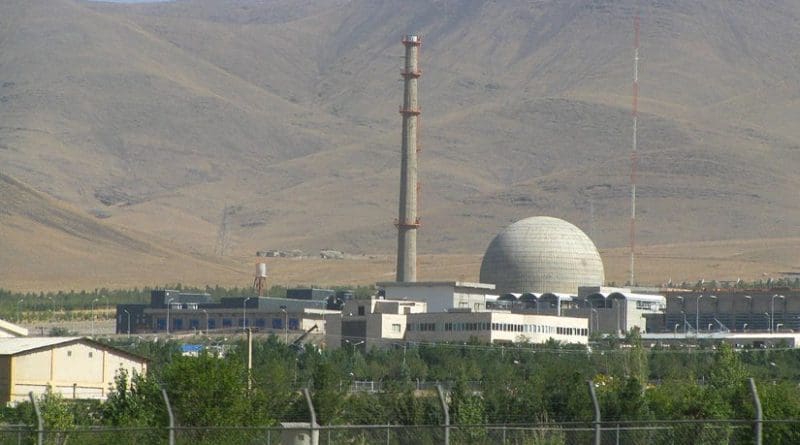

Those who claim that the deal is bad point to the fact that it allows Iran to legally enrich uranium, does not require it to dismantle any of its nuclear facilities, and permits it to continue its research and development of a new generation of centrifuges and intercontinental missile technology.

They further argue that with the relief from sanctions, Iran will have far greater financial resources to finance terrorist groups, shore up extremists such as Hamas and Hezbollah, and destabilize Sunni Arab regimes. Moreover, due to Iran’s propensity to cheat, it will be only a matter of time until Tehran realizes its long-standing goal to secure nuclear weapons.

The most objectionable part of the Iran deal, however, is that the US did not link the deal to Iran’s nefarious activities in and outside the region, which made the nuclear issue acute and unsettling.

The international outcry over Iran’s nuclear program stands in stark contrast to the reaction to India and Pakistan’s testing of nuclear weapons in 1998 within weeks of one another. Although there was worldwide condemnation and the US imposed some sanctions, they were lifted only after a few months.

Unlike Iran, however, neither country was engaged in clandestine, subversive behavior; Iran undermines regimes, supports terrorist organizations and continually calls for the annihilation of another UN member state—Israel. Were Iran not engaged in such activities, there would have been no uproar about its nuclear program and the sanctions might not have been sustained.

Delinking Iran’s conduct from the nuclear deal is ultimately self-defeating as the concerns about Iran’s nuclear weapon program stem directly from the fact that given its conduct, it cannot be trusted with nuclear weapons.

As to whether or not the deal is a “historic event,” I disagree with many who are touting it as such. By employing this kind of rhetoric, the aim is obviously to suggest that Iran has turned the page, that there is no going back to the way things were, and that in fact a new day has dawned.

But does this agreement constitute an event in the sense that it marks a radical turning point in the politics of Iran? For the philosopher Alain Badiou, a true Event allows something completely new to come into existence – it signals a kind of rupture, a break with the state of things, and a departure from dominant assumptions and prejudices: “The event is the sudden creation, not of a new reality, but of a myriad of new possibilities.”

For Badiou, the Arab Spring was an Event, when the “Egyptian and Tunisian peoples” reminded the world that “[mass uprising] is the only kind of action that equals a shared feeling about scandalous occupation by state power.” Even though the Arab Spring seems to have dissipated, it is indeed historic. The awakening of the Arab youth is still in its infancy, and any Arab regime that does not embrace the spirit of the Arab Spring will not be spared the wrath of their people, regardless of how long that might take.

The deal with Iran would certainly not represent an Event in this sense of the term – and, indeed, whether it will prove to be a historic event in any meaningful way remains to be seen. After all, Iran could very well undercut the deal by cheating, and even full compliance does not prevent it from continuing its support of murderous dictators such as Assad of Syria, and waging proxy wars to serve its national agenda.

Moreover, the deal will expire after ten years, at which point Iran will be considerably freer to pursue the acquisition of nuclear weapons, an eventuality that Israel, Saudi Arabia, and others will not sit idly by for, hoping Iran will somehow transform itself into a good and trustworthy neighbor.

That said, being that there is no viable alternative to this deal, those who support it correctly argue that the deal is good as it potentially delays Iran’s ambition to acquire nuclear weapons for at least ten years; it requires Tehran to reduce its stockpile of enriched uranium by 98 percent, disables the Arak facility from producing weapons-grade plutonium, reduces the number of centrifuges by two thirds, converts the Fordow facility into a research center, and allows for unprecedented intrusive inspections.

In addition, the deal would lengthen (from a few months to a year) the timeframe in which Iran could reach the breakout point, which would give the US more time to act, even militarily. Finally, supporters suggest that a more prosperous and secure Iran might give up its drive to obtain nuclear weapons and may even become a constructive player in the community of nations.

Now that the deal has been passed unanimously by the United Nations Security Council, it has become legally enshrined—but that does not guarantee that Iran will fully abide by its provisions, let alone cease its subversive activity.

To that end, to enforce the deal, the US must focus not only on preventing Iran from getting nuclear weapons, but how to force it to change its behavior, which was and still is the real cause that instigated international clamor against Tehran’s nuclear program.

First, now that there are open channels between the US and Iran, Washington should make it abundantly clear (behind the scenes) that Iran must cease and desist its belligerent conduct, and the US will not hesitate to undertake painful punitive actions to stop it, irrespective of the deal.

Second, notwithstanding the personal disdain between President Obama and Prime Minister Netanyahu, both will have to swallow their pride and mend their relations. This deal, however flawed, is better for Israel than no deal. Standing together will send a clear message to Tehran that nothing can compromise America’s commitment to Israel’s national security. This would significantly help sway some members of Congress from opposing to supporting the deal.

Third, the President should dramatically enhance the security of the Gulf States by offering the weapons and training necessary to warn Iran that the US will have zero tolerance to any meddling in the affairs of its allies in the Gulf. The US should also consider offering a formal defense treaty, which could certainly prevent proliferation of nuclear weapons, as Saudi Arabia and Egypt have already indicated they might pursue them in the wake of the deal.

Fourth, regardless of how eager President Obama is to sustain the deal, under no circumstances should the US permit Iran to commit any infraction connected to the deal with impunity. This will dramatically enhance the prospect that Iran fully adheres to every nuance of the deal or face terrible consequences.

Fifth, the President should take advantage of the common concerns that the Sunni Arab states and Israel share about Iran’s threat. The US should facilitate the development of a strategic plan between the two sides, some of which is already taking place, to blunt any Iranian effort to bully its neighbors.

Although President Obama views the Iran deal as his signature foreign policy achievement, he will not see it come to fruition while still in office. He will leave behind this unfinished business to his successor, and his legacy will hang in the balance for years to come before historians render their final judgment.

*Dr. Alon Ben-Meir is a professor of international relations at the Center for Global Affairs at NYU. He teaches courses on international negotiation and Middle Eastern studies.