India: Northeast Border Wrangles – Analysis

By SATP

By Ajit Kumar Singh*

The decades-old inter-state border disputes among the Indian States of the Northeast, which had flared up most recently in October 2020, only to be pushed into the background for a short span of time, have raised their ugly head again, more violently and alarmingly.

On July 26, 2021, five Assam Police personnel, including Sub Inspector Swapan Roy, and a civilian were killed along the Assam-Mizoram inter-state boundary in Kolasib District (Mizoram)-Cachar District (Assam) region. Another, 50 policemen, including Superintendent of Police Cachar Nimbalkar Vaibhav Chandrakant, and nine civilians, were injured. On July 27, one of the injured Policeman succumbed to his injuries, taking fatalities up to six.

While it is clear that a police team from Assam visited the border between Lailapur village in Cachar District and Vairengte in Kolasib District, subsequent events become hazy, with both the States accusing each other of provocation and violence. Further, though it is a fact that Assam Police personnel were killed in firing by the Mizoram Police, Mizoram accused the Assam Police of firing the first shot. It is pertinent to recall here that, though clashes between locals and the Police have been a normal feature in the border region, it is for the first time that State Police Forces have fired at each other.

This present incident did not happen all of a sudden. Media reports indicate that after the flare up in October 2020, skirmishes along the Assam-Mizoram inter-state border never stopped. Over 50 people have been injured and several houses and shops set on fire since then. The situation started worsening in the region since the beginning of July 2021, when both sides started accusing each other of encroachment on their respective territories. On July 10-11, three explosions (one in Assam on July 10 and two in Mizoram on July 11) were heard along the inter-state boundary in Kolasib-Cachar region. No casualty was reported in these explosions. On July 25, eight farm huts reportedly belonging to Mizo farmers were burnt down.

On July 11, Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma confirmed that two or three blasts had occurred and conceded,

The Assam-Mizoram border situation has remained tense for the last six months. The situation has not improved as we had expected. But in last one month, we have ensured that no one from Mizoram side can intrude into Assam.

Sarma also affirmed that Assam would protect its constitutional boundary with Mizoram with all its might.

On the other hand, on July 12, Mizoram Home Minister Lalnunmawia Chuaungo blamed Assam for encroachment and asserted that, though the Mizoram Government did not want to be the first to strike a blow on the issue, it was ready to accept any measures to protect the territory of the State.

Despite the buildup, no genuine efforts were made by either State Government or by the Government at the Center, to reduce tensions. More deplorably, on the day of the incident (July 26), while a violent mob gathered at the site of the incident and the situation was visibly deteriorating, the two concerned Chief Ministers – Assam Chief Minister Sarma and Mizoram Chief Minister Zoramthanga – engaged in an unfortunate duel on Twitter. To begin with Sarma tweeted,

Honble @ZoramthangaCMji, Kolasib (Mizoram) SP is asking us to withdraw from our post until then their civilians won’t listen nor stop violence. How can we run government in such circumstances? Hope you will intervene at earliest.

Zoramthanga replied in a tweet,

Dear Himantaji, after cordial meeting of CMs by Hon’ble Shri @amitshah ji, surprisingly 2 companies of Assam Police with civilians lathicharged & tear gassed civilians at Vairengte Auto Rickshaw stand inside Mizoram today. They even overrun CRPF personnel /Mizoram Police.

The ‘twitter war’ continued with Sarma saying that “I have just spoken to Hon’ble Chief Minister @ZoramthangaCM ji” and “I have reiterated that Assam will maintain status quo and peace between the borders of our state”, and Zoramthanga responding, “@himantabiswa ji, as discussed, I kindly urge that Assam Police @assampolice be instructed to withdraw from Vairengte for the safety of civilians.”

Nothing was done on the ground and seven persons lost their lives, demonstrating the abject failure of the people at the helm.

Sadly, at the time of writing, there is nothing to suggest that any of the three Governments (Centre and the two States) have made any genuine efforts to resolve the issue, beyond the rhetoric of “fresh negotiation… between the two governments [Assam and Mizoram] to de-escalate the situation.” At the time of writing, tension continues to prevail along the inter-State border. Mizoram claims that National Highway 306, Mizoram’s lifeline, remained closed, and no vehicle had entered the State from Assam since the July 26, 2021, clash at the border. Assam, on the other hand, asserted that the “economic blockade” staged by several non-government groups on National Highway 306 had been lifted.

Long unresolved inter-State border disputes are not limited to the confrontation between Assam and Mizoram. Indeed, Assam Chief Minister Sarma in a written reply in the State Assembly on July 12, stated that a total of 209 instances of encroachment of Assam land had taken place since 2016, when the Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP) came to power in the State for the first time. These encroachments were carried out by people from Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Mizoram and Meghalaya, he added.

On the other hand, these States have long blamed Assam for encroachments.

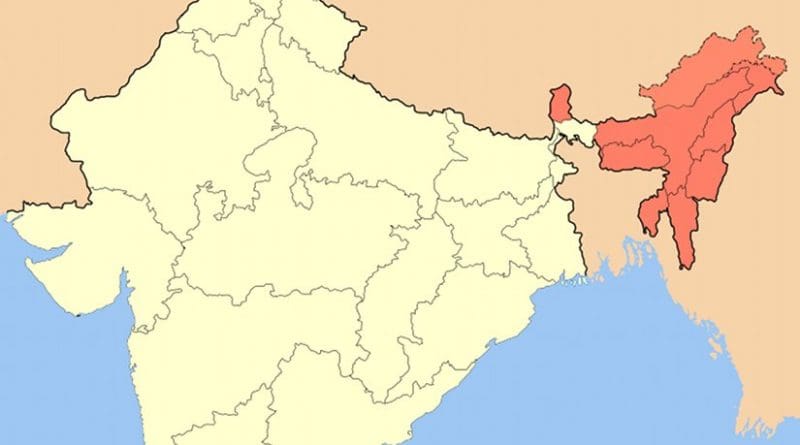

The inter-state border disputes are mainly between Assam and six other States with which Assam shares its borders: Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Tripura. The dispute is more complex and intense between Assam and four of these States, which were formed after independence: Arunachal Pradesh (Union Territory 1972, State 1987), Meghalaya (Autonomous State 1970, full-fledged State 1972), Mizoram (Union Territory 1972, State 1987) and Nagaland (1963).

At the core of the Assam-Arunachal border dispute is the 1951 boundary delineation notification. Arunachal refuses to accept it as the basis of boundary delineation, arguing that the 3,648 square kilometers of the plain areas of North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA), as Arunachal was known in 1951, were transferred to the then undivided Darrang and Lakhimpur Districts of Assam at the recommendations of the Bordoloi Committee, without the consent of its people. The border dispute between Assam-Meghalaya arises out of Meghalaya’s refusal to accept the Assam Reorganisation (Meghalaya) Act of 1969. There are at present 12 points of dispute along this border covering an area of 2,765.14 square kilometers.

The boundary between Assam and Mizoram is defined in the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act of 1971, which in turn is based on Notification No. 2106, AP dated March 9, 1933. However, at the root of the Assam-Mizoram border dispute is a notification of 1875 that differentiated the Lushai Hills (Mizoram) from the plains of Cachar, and the 1933 notification, that demarcates a boundary between the Lushai Hills and Manipur. Mizoram believes the boundary should be demarcated on the basis of the 1875 notification, which is derived from the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation Act, 1873, and not as per 1933 notification which the Assam Government accepts. According to Mizoram, in the 1933 demarcation, the Mizo society was not consulted. Indeed, the most recent flare up at the Assam-Mizoram inter-state boundary was over a small piece of land in a forested area. According to reports Mizoram police was constructing an 8×8 feet post atop a hillock in Vairengte for its personnel to “secure their area.” The Assam Police claimed the post was being built in the Inner Line Forest reserve area, which was ‘illegal’. Mizoram claims all of its posts fall in Vairengte; while Assam insists they come under Rengti Basti, an inner-land forest reserve area within its boundaries. The Mizoram Government accused the Assam officials of encroaching into an area called Aitlang Hnar (the source of river Aitlang), around five kilometers from Vairengte in Mizoram, and destroying plantation crops. Assam, on the other hand, alleged that Mizo residents had encroached upon 6.5 kilometers of land inside the Assamese territory and planted banana and betel nut saplings, besides constructing makeshift settlements.

Though the dispute between Assam and Nagaland started soon after the latter attained statehood in 1963, it is important to note that even before 1947, when India became independent, the Naga National Council had demanded the return of the territories which formed part of the Naga Hills District. Indeed, the restoration of the “Naga areas” was raised and placed on record in the 16-Point Agreement signed between the Government of India (GoI) and the Naga People’s Convention in 1960. GoI did not honor this agreement and the State of Nagaland Act, 1962 was enacted, defining its borders based on the 1925 notification. Since then, Nagaland has not accepted the boundary delineation and demanded that Nagaland should comprise the erstwhile Naga Hills and all Naga-dominated areas in North Cachar and Nowgong (Nagaon) Districts, both in Assam, which were part of Naga territory in 1866. Nagaland demands 12,488 square kilometers of Assamese territory, mostly coverered by 10 Reserve Forests.

Most recently, Nagaland protested after the Assam Police allegedly tried to set up a camp close to Vikuto village under Tzurangkong range in the Mokokchung District of Nagaland on June 29, 2021. The area is near Mariani in Assam’s Jorhat District. The tension had started to build but, before it could worsen, better sense prevailed, and Assam Chief Minister Sarma tweeted on July 31,

In a major breakthrough towards de-escalating tensions at Assam-Nagaland border, the two Chief Secretaries have arrived at an understanding to immediately withdraw States’ forces from border locations to their respective base camps.

However, the agreement seems fragile. Indeed, on July 30, Nagaland’s Deputy Chief Minister Yanthungo Patton had claimed that, in past settlements between the two Northeastern States, both Police forces had agreed to withdraw from the border areas, but Assam failed to comply and had, in fact, increased Police presence, while Nagaland withdrew its forces. “We will not make the mistake again,” he said, showing long-standing distrust.

Meanwhile, on July 26, Meghalaya accused the Assam police of trying to remove electricity poles inside Longkhuli village in Ri Bhoi District (Meghalaya) along its border with Assam. Interestingly, just three days earlier, on July 23, Sarma had met the Meghalaya Chief Minister Conrad Sangma to discuss the border dispute between these two states. During the Assam-Mizoram border flare up in October 2020, Meghalaya had also demanded the resolution of its border issue with Assam.

There are other inter-State border disputes in the region, including those between Mizoram and Tripura, one of which had flared up in August 2020 and had worsened in October that year.

The reality is that the prolonged inter-State border disputes in the region have not been genuinely addressed by any of the Governments, past and present, for reasons best known to them. These Governments have failed appallingly to understand the intrinsic nature of the inter-State border issues in the region, or to make a serious attempt, in good faith, to address these.

Significantly, the latest firing incident (July 26) happened just a day after Union Home Minister Amit Shah visited the region (July 24-25), and met with the Chief Ministers of all the eight Northeast States. In the meeting he had requested the Chief Ministers “to resolve the border disputes of the States expeditiously in a cordial atmosphere by mutual consultation.” Vote-bank politics, which make State leaders fearful of losing support of one group or the other, has played a crucial role in the unfortunate persistence of these disputes.

It is, consequently, highly unlikely that these border issues are going to be resolved any time in the near future. The fragile peace established in the entire region after decades of armed conflict, therefore, remains under constant threat, as the possibility of these disputes being exploited by weakened and dormant terrorist groups of the region is very real. The challenges for the Security Forces on the ground are, therefore, likely to grow further.

*Ajit Kumar Singh, Research Fellow, Institute for Conflict Management