Asia Pacific’s Runaway White Elephant Projects

Driving down Timor Leste’s four-lane South Coast Highway, one cannot but marvel at the desolateness of a multimillion-dollar highway. But the deserted look is surpassed by the deathly quiet of the destination — the Xanana Gusmao International Airport at Suai.

Together the ‘superhighway’ and the airport have already cost Timor Leste US$620 million. They are part of the Tasi Mane mega project costing anywhere up to US$14 billion that includes a petroleum complex, which currently has few takers and offers very little benefit for ordinary Timorese.

Timor Leste’s economy is dependent on its limited oil reserves. According to a 2018 study published in Resources policy, Timor Leste has, for the last 15 years, been operating a petroleum fund “to provide a stable source of revenues for the budget over the long term and to preserve intergenerational equity [i.e. equity or fairness in terms of relationship among seniors, adults, youth and so on]”.

But withdrawals from Timor Leste’s petroleum fund, said the study, are high compared to the country’s estimated income from oil. According to Basudev Pradhan, assistant professor of energy engineering and former visiting scientist at the University of Central Florida, US, Timor Leste can ill-afford to drain out funds for white elephant projects because the oil reserves are limited, and production may cease by 2023.

“Funds should be spent cautiously in Timor Leste; mismanagement of funds should be avoided at any cost,” Pradhan tells SciDev.Net.

Home of the white elephant

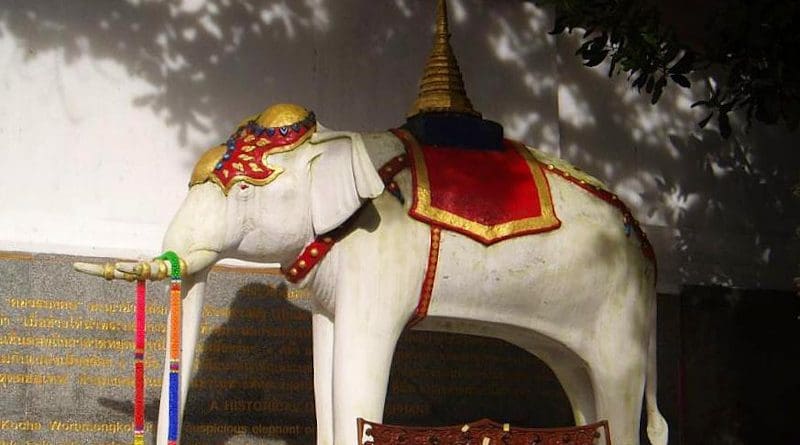

But such mindless spending on doomed projects are not unusual in the Asia Pacific region, the original home of the white elephant. Historically, when a Thai (Siamese) king wished to ruin a tiresome noble he would gift the man a sacred white elephant which could neither be put to work nor sold away. The upkeep of the large and idling beast was sure to ruin the helpless noble.

Similarly, modern versions of the white elephant show up helplessness in the face of certain ruin. Take India’s coal-fired thermal power plants. Although they have a reputation for being inefficient and polluting, the state-owned Power Finance Corporation has continued to fund them for years, accumulating bad loans worth US$6.8 billion by the beginning of 2020.

It does not seem to matter that phasing out coal is known to be the most effective way to achieve the emission reductions needed to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius as required by the Paris Agreement. Indeed, new coal-powered plants continue to be added to a grid already burdened by overcapacity.

In November, the Indian government eased up environmental clearance regimes for power plants to allow them to use domestic coal, the production of which has been ordered ramped up. Coal, the most carbon-intensive of all fossil fuels, also continues to be imported to keep the power plants running.

Other governments in the Asia Pacific region are also saddled with dodgy governmentpolicies that lead to either overfunded white elephant projects or potentially impactful science ventures that languish for lack of funds.

“White elephant research endeavours will occur in every country, and clearly they are even more regrettable in low- to middle-income countries because of the waste of financial resources,” says Dirk Pfeiffer, director of the Centre for Applied One Health Research and Policy Advice, City University of Hong Kong.

For large infrastructure projects related to science, technology and health — such as nuclear power plants, science parks, health care related schemes, bridges, highways, airports — developing countries typically arrange their own funding often in collaboration with other countries.

A science venture becomes a ‘white elephant project’ when the project’s capital costs are high, extremely expensive to run and is of little use or practical value and the returns insignificant. These projects are often carried out to fulfil the interests of government or private authorities, and typically lack transparency in project approval mechanisms.

“Using modern-day language in the scientific world, a white elephant project is one that seems to be non-viable from an economic or functional viewpoint,” says Anish Ray, a medical scientist at the Cook Children’s Medical Centre, Texas, US.

“Unfortunately, these projects exist in all parts of the world and most predominantly in the public sector. While multifactorial, primary reasons for the existence of white elephant projects include lack of oversight and specific expertise,” says Ray. “Additionally, feasibility of the project is overlooked,” he tells SciDev.Net.

Jatropha biofuel fizzles out

Shantanu Panja, a science research analyst affiliated to the Apollo Gleneagles Hospitals, Kolkata, India, says that “sometimes, white elephant projects become political face-saving exercises, or a public spectacle rather than a utilitarian project”.

Panja cites biofuel projects in South-East Asia that never really lived up to the hype. Despite substantial subsidies and incentives, South-East Asian initiatives to join the global biofuel development segment enjoyed little success.

For instance, Indonesia, which started research on growing jatropha for biofuel production in 1994 and hyped it as ‘green gold,’ encouraged farmers across the country to cultivate the crop by providing support through research and credit subsidies. One large subsidy of about US$11 million was handed out in 2007 — which led to some 8,000 contracted farmers growing jatropha on 17,000 hectares.

By 2008, jatropha was planted over an estimated 900,000 hectares globally of which 85 per cent was in Asia with Indonesia projected to be the largest producer in 2015 with 5.2 million hectares out of the estimated 12.8 million hectares globally. But in less than a decade, jatropha as a biofuel failed and became an example of a well-intentioned climate mitigation approach gone wrong.

On 17 December, Eddy Abdurrachman, chief of Indonesia’s Crop Fund, said at a virtual conference that the body had, in 2020, spent US$1.82 billion in subsidies on biofuel programme, which was more than the US$1.2 billion raised though export levies.

Similarly, the Philippine government once touted jatropha as a promising energy-saving project and embarked, about a decade ago, on a massive cultivation programme on more than 4,000 hectares that was meant to be a source of biodiesel.

By 2013, a subsidiary of the state-owned Philippine National Oil Company admitted that the jatropha project was a failure and that the country had wasted some US$20 million on it. As was found out too late, the wild plant, mostly used in traditional medicine in the country, was not commercially viable. The programme was abandoned, leaving thousands of frustrated farmers high and dry.

Science and technology parks

Inspired by the success of Silicon Valley, many countries in the Asia Pacific put up science and technology parks. When done right, a science and technology park can become a good hub for innovation and a source of national pride. Some of the successful ones in the region are found in China, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand and Vietnam.

However, establishing a science and technology park is not easy and there are many failed examples. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development noted in a paper that only 25 per cent can be considered successful. The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific has warned that science and technology parks could easily turn into white elephant projects.

Cyberjaya in Malaysia, a science park that is considered as an entrepreneurial centre for information technology, has fallen short of desired output.

A report by a Kuala Lumpur-based think tank, Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs, Cyberjaya “has not been successful in realising the vision of transforming Malaysia into a global information and communication technology hub”.

The report notes that exports of information and communication technology have not shown any increase in Cyberjaya in relative terms. It adds that “the spark of entrepreneurship and risk-taking, which has defined Silicon Valley [in the US] since the sixties, is not a common sight in the Malaysian Silicon Valley…there is not much of a risk-taking private venture capital and entrepreneurial culture”.

“The interface between scientists and policy makers is much weaker and often non-existent in many Asian and Pacific countries [including Malaysia], and career development of academics and research scientists tends to be purely dependent [on the output of research] publications within their discipline,” Pfeiffer explains to SciDev.Net.

This difficulty of scientists and academicians handling policy and management is visible in the failed science and technology park in the University of the Philippines, Los Baños — today an odd and unimpressive set of four buildings. Even after spending close to half of its US$14.8 million estimated funding, the park is bereft of tenants and far from earning returns on the investment. Part of the problem is that it was left to academicians and scientists in the university to handle and operate the business park, something which they are not familiar with.

According to Deepanjan Mitra, secretary, Society of Nuclear Medicine, India, the problem may stem from scientists’ excessive theory-based approach while considering and working on science projects. He says that in South and South-East Asian countries, many scientific projects are at theoretical levels with no thought given to practical utility.

“Even studies and papers [that] look good at conceptual levels do not translate into something practical,” Mitra tells SciDev.Net.

Pradhan adds, “A science and technology park in a country like the Philippines needs to be maintained and upgraded thoroughly so that people can take interest in it. In Asian countries such as China, Japan, and Thailand, successful operations of science and technology parks generated revenues and empowered the economy. The Philippines, too, should work in this direction.”

Wild wasteful endeavours

The South Asian developing country Sri Lanka took up in September 2019 an ambitious project to use drones to carry drugs and blood products to particular locations carried out by a US company called Zipline. The project, however, could be a white elephant initiative, say experts, owing to its costs in comparison to yields. Previously, Zipline was involved in projects related to drone use in Haiti (for food and medicine supply), and Rwanda (for emergency blood supply).

Road transport of essential drugs and blood products is a hassle-free and financially affordable measure as far as Sri Lanka is concerned.

“In Sri Lanka, when there is a stable system for the delivery of essential medicines and blood, misspending of funds for promoting the unnecessary and costly drone delivery (of essential medicines and blood) is a white elephant project,” says Ray.

Diptendra Sarkar, professor of surgery and public health strategist affiliated to the Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research, Kolkata, India, agrees. “For developing Asian countries (such as Sri Lanka), it is important to avoid white elephant projects as these projects can adversely affect financial situation of individuals and communities.”

Nepal — with support from World Health Organization—had taken up an action plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases five years ago. But, thanks to the negligence of some government officials, the project has yielded no results. On paper, it is run by 17 ministers and organisations working under their ministries, governments in provinces, and federal units active at the local levels.

“As far as the 2014-2020 action plan in Nepal is concerned, there are several committees, ministers, and representatives from organisations, but there is no action on the field, which makes this action plan a white elephant project,” says Sarkar. “The action plan is expected to be updated by the government for 2020 to 2025,” he tells SciDev.Net.

In fact, Nepal is currently facing a double burden of a rising trend in non-communicable diseases (NCDs) added to communicable diseases that will add great pressure on an already fragile health system. While the primary health care approach offers a common platform to effectively address NCDs through preventive and curative interventions, its potential remains untapped.

What must be done

Every country has white elephant projects, and it’s mostly the costly projects that appear as white elephants. Along with adopting country-specific strategies to avoid white elephant projects, experts have urged scientists and policy makers to take up measures for self-evaluation.

Mitra says: “Hierarchical and bureaucratic structures of science research organisations often don’t engage in self-evaluation as to whether the research projects are truly worth it or not. We need to open up the research grants to genuine researchers across private and government agencies and not look only at their biodata.”

There is also the issue on how funding should be treated especially if it comes from science ministries which are seen to provide funding support as part of their mandate but with little interest on returns or income.

Philippine science secretary Fortunato dela Peña explains that generating income for funding projects is not part of the department’s equation. However, he does recognise the need for accountability, which is why under his term he implemented the 6 Ps (publication, patent, product, people services, places and partnership, and policies) in 2018 as a quantitative means to measure the impact of the funded projects.

Overall, the Asia Pacific experience has been that white elephants result from the political capture of mega projects, making them susceptible to vested interests and lose sight the original goals of economic development. Worse, the operation and maintenance of these projects continue eat into national budgets long after they are recognised as unviable.

With additional reporting by Joel Adriano and Ranjit Devraj.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Asia & Pacific desk.