Ukraine: War Crimes Against Cultural Heritage

By IWPR

By Tetiana Kurmanova

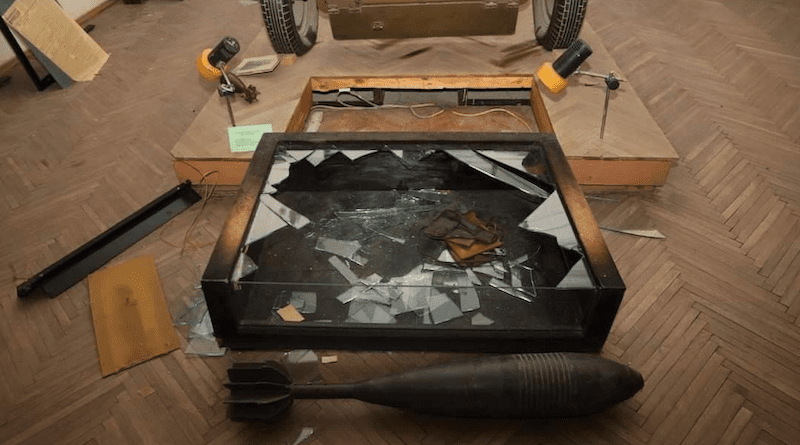

The Kherson regional history museum used to have one of the most impressive collections of its kind in Ukraine, with treasures from pre-history to the modern era.

When Russian soldiers fled the Kherson region in the face of a Ukrainian counter-attack in November, they ransacked the entire collection.

Vast swathes of the collection were systematically looted, including gold and silver artefacts, items from ancient Scythian and Sarmatian burials, rare ceramics, weapons and the entire numismatic collection.

According to Ukraine’s minister of culture, Oleksandr Tkachenko, some 80 per cent of the museum’s contents were stolen.

His deputy, Kateryna Chuieva, said that with the region still under attack, the full extent of the losses may be yet to emerge.

“Documenting all the losses in the museums of Kherson will take time because it is still dangerous,” Chuieva said, adding that investigators were currently recording and collecting evidence for future criminal proceedings.

Across Ukraine, experts and officials are documenting the huge scale of cultural destruction wreaked by Russian forces with the aim of launching war crimes cases against the perpetrators.

Tymur Korotkyi, vice-president of the Ukrainian Association of International Law, stressed that

the theft of cultural values – whether in private or state-owned collections – could be considered a serious violation of international humanitarian law and a war crime. It falls under Article 8(2)(a)(iv) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

“According to international humanitarian law, cultural items have a higher level of protection compared to civilian objects,” Korotkyi said. “Such violations of international humanitarian law are war crimes, ie when there are deliberate attacks on cultural objects, or deliberate attacks on civilian objects when cultural objects are damaged as a result of the attack, and in the case of indiscriminate [or] disproportionate attacks also looting or appropriating cultural values. Also, the destruction, damage, and destruction of cultural values can indicate crimes against humanity and genocide.”

As of mid-December 2022, according to ministry of culture data, 1,132 items of cultural infrastructure had been damaged with 403 completely destroyed. These include architectural monuments, museums, schools, universities and cultural centres.

The regions of Kyiv, Kharkiv, Luhansk, Mykolaiv, Zaporizhzhia, Sumy and Kherson have been affected, with Donetsk the hardest hit; 80 per cent of its cultural infrastructure had been damaged.

The drama theatre in now-occupied Mariupol, destroyed by an airstrike, became one of the most egregious symbols of Russian war crimes. Other cultural heritage sites damaged include the house of the 19th century Ukrainian philanthropist Vasyl Tarnovskyi in Chernihithe, the museum of famous artist Maria Prymachenko near Kyiv and the hermitage of Sviatohirsk lavra, the largest wooden church in Ukraine, in the Donetsk region.

As in Kherson, Russian forces have also been removing collections wholesale from other Ukrainian museums. The Mariupol city authorities reported that the occupying forces took away items including original works by city native Arkhyp Kuindzhi as well as artists Ivan Aivazovskyi and Mykola Dubovskyi and three 19th century icons.

In the local history museum in occupied Melitopol, Zaporizhzhya region, a collection of Scythian, Hunnic and Sarmatian gold as well as silver coins from the Dukhobora treasure were stolen.

According to Yaroslava Savchenko, a culture expert at the Foundation for the Support of Fundamental Research NGO, no one knows the exact amount of cultural heritage destroyed in Ukraine, partly because records have yet to be digitally updated.

Chuieva confirmed this, adding, “Until recently, we did not have mandatory records in purely electronic form, and there were no programmes for the digitisation of museum collections.”

She said that the ministry had started the process of synchronising various records, and a presidential initiative had also begun gathering detailed information on all affected objects.

The data collected will be processed by national law enforcement agencies and transferred to international partners, in particular, Interpol and organisations that oppose the illegal traffic of cultural items.

“We have international humanitarian law and international conventions on our side,” Chuieva said. “Together with the prosecutor general’s office, we will consider various possibilities of defence in international institutions. In particular, Ukraine will prepare a submission to the ICC.”

Korotkyi noted that modern technology allowed possible war crimes against cultural heritage not only to be recorded in real time but also disseminated at an international level.

“This is important in the context of preventing the illegal international circulation of cultural values of Ukraine stolen by Russia,” he continued. “It is necessary to constantly monitor auctions and the commercial circulation of cultural values on online and offline sites, informing the organisers about the presence of stolen Ukrainian objects.”

Ukraine is also lobbying for the creation of a Special Tribunal to try Russia for the crime of aggression, which will consider all its consequences, including the destruction of Ukraine’s cultural heritage.

“Also, with regard to war crimes against cultural values, the jurisdiction is, first of all, of the law enforcement agencies of Ukraine, as well as foreign law enforcement agencies, in accordance with the principle of universal jurisdiction, and, of course, the International Criminal Court,” Korotkyi said.

Nonetheless, he warned that Ukraine needed to ensure it upheld international standards of documentation in its investigations of these particular crimes. In addition, Article 438 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, which establishes criminal liability for violations of the laws and customs of war, needed to be updated in particular with regard to specifying war crimes against cultural values.

Savchenko said that all Ukraine’s cultural treasures, where state or privately owned, had to be returned.

“Such return mechanisms exist: either during the conclusion of an agreement between states after the end of hostilities or on the basis of decisions of international judicial institutions [and] arbitration institutions,” she said.

While all accept that the process will be long, officials and experts remain adamant that the preservation of national identity is a vital part of the war effort.

Hanna Yarmish, head of the scientific and educational department of the Hryhorii Skovoroda national literary and memorial museum in the Kharkiv region, stressed that cultural values were inherently intangible.

The museum, dedicated to a renowned Ukrainian philosopher, was severely damaged by Russian rockets in May 2022, although officials said that its most valuable exhibits had been removed to a safe place.

Yarmish concluded, “Only physical objects can be destroyed with a rocket, never spiritual ones.”

This article was published by IWPR