Arab Revolutions Leave Al-Qaeda Behind

By Magharebia

By Rajeh Said

The two popular revolutions that toppled former presidents Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia and Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak constituted a new challenge to al-Qaeda and its ideologues.

This challenge did not arise after a targeted military strike or additional restrictions on the movements of al-Qaeda leaders in their preferred staging areas on the Afghan-Pakistan border.

Instead, the challenge is the result of a wish that came true: the fall of regimes routinely described as “dictatorial” or “apostate” for ruling in a manner contrary to the teachings of Islamic Sharia.

But the irony is that the realisation of this wish created a thorny ideological problem for al-Qaeda leaders. Regimes described as dictatorial and oppressive can be overthrown by peaceful popular uprisings and not only through armed action, which some jihadists had long insisted was the only way to achieve regime change.

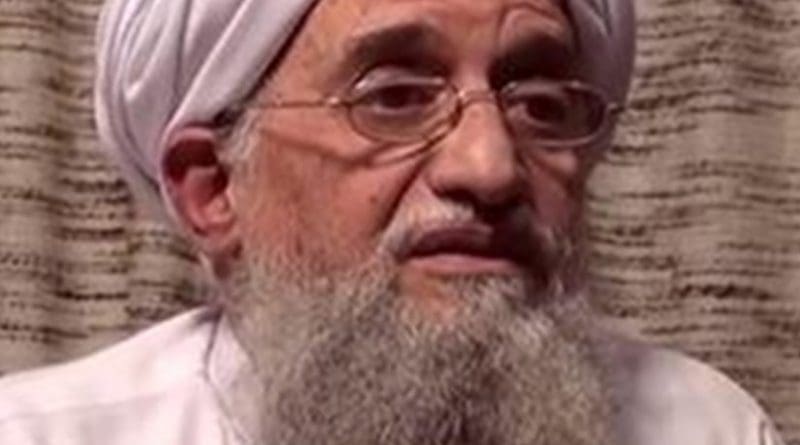

Al-Qaeda’s intellectual dilemma came to the forefront immediately after the Tunisian and Egyptian regimes fell. Dr Ayman al-Zawahiri, al-Qaeda’s second in command, recorded a series of messages apparently made just days before Mubarak resigned, following street protests that brought millions of peaceful demonstrators to the Egyptian streets calling for “the fall of the regime”.

The messages were al-Zawahiri’s first comments on the popular uprising in Egypt. In them, he attacked the Mubarak regime for presenting itself as a secular and democratic regime that uses Islamic Sharia as a source for legislation and not the sole source. He also criticised it for saying that sovereignty stems from the people.

Al-Zawahiri called Mubarak’s regime a “Jahilia” regime (meaning un-Islamic) and said that the “democratic process can only be secular and not religious”. He lashed out at states with democratic systems, showing disdain for Islamists who are calling for the adoption of “the system known as the civilian state”.

Al-Zawahiri’s statements appeared out of touch with the aspirations of young men and women who took to the streets in Egypt and Tunisia to call for real democratic regimes to replace what they viewed as the corrupt regimes of Mubarak and Ben Ali.

His words were reminiscent of a video message released years ago, in which he said change in Islamic countries cannot be accomplished in a peaceful manner. In that message, which was posted on discussion forums along with his latest one, he challenged those who do not share his opinion to provide “one example” of a peaceful revolution that succeeded in changing a regime.

While al-Zawahiri’s messages, both old and new, were being posted online, Egyptian Vice President Omar Suleiman announced that Mubarak was stepping down, meeting the demand of the protesters. The Egyptian army, which assumed power during a transitional period, appeared to be serious about meeting the aspirations of protestors. Demonstrators sought Mubarak’s departure, a campaign against rampant corruption in state institutions, and constitutional amendments that would open the door to real democracy that allows for the peaceful transfer of power, political pluralism, and press freedoms.

The Egyptian authorities began immediately to prosecute former regime officials for involvement in corruption and amending articles of the constitution to allow greater competition for the presidency and for parliamentary seats. The new leadership also started licensing political parties that were awaiting approval for 20 years such as the Centre Party, which was founded by former leading figures of the Muslim Brotherhood.

The brotherhood appears to ready to make the transition into a legal party after being banned for several decades.

Decades of violence brought oppression, not change

The ability of the Egyptian population to change the regime through peaceful demonstrations brings to mind three decades of security turmoil that Egypt witnessed because jihadists like al-Zawahiri insisted on the use of violence and armed action as the only ways to change the regime.

Jihadists assassinated former President Anwar Sadat in 1981. The next regime, led by Mubarak, reacted by imposing an emergency law, violently suppressing Islamists, and preventing any political activity that could lead to any change in the regime (as exemplified by the dissolution of the Labour Party and the prevention of the Muslim Brotherhood from participating in political life).

This security and political crackdown was reinforced throughout the 1990s because the jihadists continued with more acts of violence against symbols of the state – such as politicians and security officials – as well as Western tourists who visited Egypt, and who constitute an essential part of the livelihood of a large segment of Egyptian workers in the tourism sector.

This became the formula offered by Egyptian officials when foreign visitors raised the issue of opening the way for greater political freedoms: any easing of the iron grip through which the regime holds various segments of society will usher the Islamists into power, they would argue.

Some officials accepted this argument and ignored for many years the human rights violations and the political and security crackdowns that occurred in Egypt, along with other “police” states. Others attempted to persuade Egypt and other countries that political reforms and acceptance of popular demands could help and not threaten efforts to combat al-Qaeda and those described as Islamist militants.

However, the Egyptian regime was quick to dismiss calls for political liberalisation, arguing that it would allow the Islamists to obtain power as happened with the Muslim Brotherhood during the Egyptian People’s Assembly elections in 2005 and with Hamas in the 2006 Palestinian elections.

Despite the fact that this argument may be true to some extent – i.e. that elections may bring Islamists to power – the fundamental weakness, it appears, is the confusion between political Islam and al-Qaeda. In fact, there is a fundamental difference between political Islam and the jihadist movement because the latter uses armed violence as an essential means – sometimes the only means – for regime change.

Political Islam vs. al-Qaeda

Perhaps the most fundamental difference between political Islamists and al-Qaeda is their differing view towards political pluralism. While the brotherhood accepts it and defends its participation in parliaments that include non-Islamist parties (which may be secular or national), al-Qaeda and other jihadist movements with a similar ideology do not accept this at all. They reject what they consider as “infidel parliaments” (since they control personal status laws), reject multi-party systems, and refuse to accept any democratic transfers of power.

The Tunisian Islamic Revival Movement was among the first Islamist groups that responded to this line of thought, which argues that it is not permissible for Islamists to abandon power if they lose elections. This Tunisian group stated, in reviews in the 1990s, that it would give up power if Islamists lost the elections.

It is likely that this debate between political Islam and al-Qaeda will resurface, with the former preparing to engage in electoral contests to be held in the coming months in both Egypt and Tunisia. It is also likely that their political participation will be met with opposition from supporters of al-Qaeda on the pretext that it is contrary to the correct teachings of Islam.

Aspects of this debate began to appear in some reactions to al-Zawahiri’s message, which was titled “A Message of Hope and Glad Tidings to Our People in Egypt”.

“Egyptian Dream”, a participant in the Aljazeeratalk forum where al-Zawahiri’s messages were posted, wrote, “Anyone who thinks that knowledge is the preserve of himself alone, and that anyone who disagrees with him is an infidel, as al-Zawahiri thinks, or a traitor, as Mubarak thinks, is a dictator to whom we won’t listen, and whose opinion we won’t care about. As for the dictatorship of Hosni (Mubarak), it was overthrown with our own hands and not through the speeches and messages of al-Zawahiri.”

Zareef, another contributor to this forum, wrote, “I think that some of the brothers have listened to the message, but in what world, and in what age, does Sheikh al-Zawahiri live? The youth of the Arab world and the Muslim world want to deal with reality and build the future. Here is the sheikh who still lives and talks to us about the history of 1800 and the foreign occupation of our country, and he did not even manage to (stay current and) reach the present time to congratulate the youth of Egypt and Tunisia on the overthrow of the regimes in their countries.”

He added, “Our youth live in the 21st century and the era of the Internet and mobile communications, Facebook, Twitter. Young people are hoping for progress to catch up with the rest of the world. Here he is giving us a lesson in ancient history from which this country has liberated itself. O sheikh, O wise man of the nation … Evolve and register yourself on Facebook, and join the January 25th revolution, and tweet so maybe you can hear the latest news: Mubarak has stepped down from power.”

Al Qaida is a ‘Front’ for the neocon’s New World Order.Their sevices are required when any

government in selected region refuses to obey the dictates of the Order.If the present setup in Cairo and Tunis swing in different direction

from the neocon requirements,Al Qaida will come

into action.