Welcoming Ukrainian Refugees: Challenges And Uncertainties – Analysis

The influx of millions of Ukrainian refugees into the EU poses challenges of management, funding and integration, but has attracted unprecedented political support.

By Carmen González Enríquez*

For the first time the EU has invoked its Temporary Protection Directive to provide refuge for the millions of displaced people who are leaving Ukraine following the Russian invasion. Their arrival has been met by complete acceptance on the part of European society, including the xenophobic parties. In the short term the wave of refugees poses challenges of funding, coordination and management, and in the long-term challenges for integration, in a context of uncertainty about the duration of the war and the volume of refugees it is likely to create. The contrasting reception given to people fleeing Ukraine compared with those seeking refuge in Europe from other parts of the world stems from various factors: a significant one is the way Europeans sympathise and identify with the Ukrainians’ plight in their struggle against the Russian invasion.

Analysis

Shortly after Russian troops launched their invasion of Ukraine, the UN warned that the number of refugees leaving the country could approach 4 million. Now, after five weeks of war, and with a large part of Ukraine still unaffected by bombing, the figure cited by UNHCR, the UN refugee agency, has already exceeded that level (4,215,000 according to data published on 3 April). This number is not only the largest exodus in Europe since the Second World War, as frequently pointed out, but also one of the largest in the world since that time.

The Ukrainians who have left their country, overwhelmingly women and children (Ukraine forbids men aged 18-60 to leave), have been met with open arms across the EU’s border states. These countries, in addition to Moldova, are receiving the bulk of the arrivals. Moreover, they have been greeted by a range of civic initiatives, both in the border states and the rest of the EU, which have been set up to receive the refuges at the frontiers, relocate them and provide them with shelter.

| Country | Source | Date | Refugees |

| Poland | Government | 3/IV/22 | 2,451,342 |

| Romania | Government | 3/IV/22 | 643,058 |

| Republic of Moldova | Government | 3/IV/22 | 394,740 |

| Hungary | Government | 3/IV/22 | 390,302 |

| Russian Federation | Government | 29/III/22 | 350,632 |

| Slovakia | Government | 3/IV/22 | 301,405 |

| Belarus | Government | 3/IV/22 | 15,281 |

After the European Council invoked the Temporary Protection Directive on 3 March, Spain was one of the first member states to apply it and to do so in its broadest terms, offering refuge not only to Ukrainian nationals but also citizens of other countries who were living in Ukraine with permanent or temporary residence permits and have fled the war. According to figures released by the International Organisation for Migration, around 500,000 refugees fleeing Ukraine are nationals of other countries.

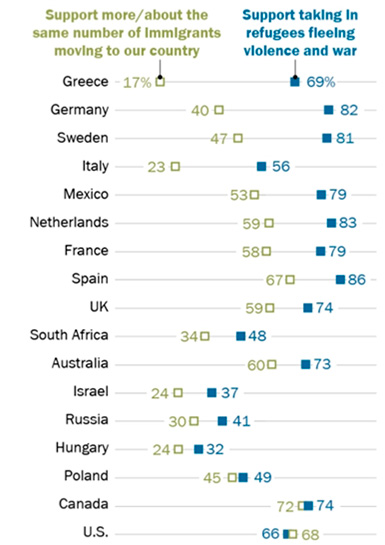

The application of the Temporary Protection in Spain includes those Ukrainians already in the country prior to the start of the Russian invasion, thus providing a route towards legalisation for those who had acquired an irregular status once they had exceeded the maximum time permitted to remain as tourists (three months). These are estimated to number around 15,000 people (calculated as the difference between the number of people registered at town halls and those granted residence permits). In choosing to apply the Temporary Protection Directive as broadly as possible, the government is in line with Spanish public opinion, one of the most positive in Europe towards the taking in of refugees, as became evident in the 2015 crisis. On that occasion relatively few sought refuge in Spain, but the surveys conducted in that and subsequent years revealed a notably welcoming attitude on the part of Spaniards.

Another sign of this particularly favourable attitude towards refugees in Spain is the fact that Spanish citizens rank first in the world in their individual contributions to the UNHCR. In terms of overall contributions, Spanish citizens occupy sixth place.

| Donor | US$ |

| US | 1,872,206,682 |

| Germany | 488,348,148 |

| EU | 326,645,601 |

| Japan | 140,577,508 |

| Sweden | 122,980,123 |

| Private donors in Spain | 121,096,767 |

| Norway | 107,423,101 |

| France | 101,200,082 |

| Denmark | 101,160,855 |

| Netherlands | 91,917,024 |

The bulk of the refugees are arriving in the Schengen Area through Poland, which is now home to more than 2 million Ukrainian refugees, more than half the total. The onward distribution of refugees from the neighbouring Eastern European countries towards Western Europe is taking place naturally in accordance to their proximity, the resources being offered and the size of Ukrainian communities within each country. Ukrainian citizens are exempt from the visa requirements for moving within the Schengen Area, an exemption that in recent years has facilitated migration into the EU and the formation of Ukrainian communities in the member states. Such communities are playing a highly active role in taking in refugees and constitute a significant factor differentiating the attractiveness of certain countries compared to others.

Germany and Italy, each with around a quarter of a million Ukrainians, were the two most attractive Western European destinations for Ukrainian immigration prior to the invasion, with Spain occupying third place (115,000 immigrants born in Ukraine on the electoral register in 2021). By the end of March, Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic had each taken in more than 200,000 refugees, Italy had taken in around 60,000 and Spain around 35,000. The real number of arrivals is much greater because the registration process, despite being very fast, cannot automatically record all those who enter by freely crossing the Schengen Area and are taken in by Ukrainian family members and friends. The Ministry of Inclusion in Spain estimates that 70,000 refugees had arrived by the end of March.

This is the first time Spain has received such a high number of refugees in such a short period. The reception system was already overstretched prior to the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but it has reacted rapidly and efficiently, offering an appropriate number of reception centres and specific fast-track procedures. The capacity for reception rests to a large extent with Ukrainian immigrants, who are taking fleeing family members and friends into their homes.

Taking in such a large number of refugees poses numerous challenges and uncertainties for European states: (1) a logistics and coordination challenge; (2) an economic challenge both for the member states and the EU; (3) an integration challenge; and (4) unanimous support for providing refuge.

(1) A logistics and coordination challenge

This is the most urgent problem that arises immediately. Central state resources are insufficient for adequately housing and protecting the high number of refugees coming from Ukraine. Moreover, the refugee response in many states has primarily taken place on a local basis (this is the case in Poland, for example) involving the spontaneous initiatives of members of the public, acting as individuals or as organised platforms assembled ad hoc.

This rapid response on the part of citizens poses a management and coordination challenge to ensure the efficiency of the efforts, and also to avoid possible problems of security, with a view to protecting Ukrainian women from sexual and occupational exploitation and identifying and protecting minors to prevent the trafficking of children. In the medium term, these disparate initiatives will force central governments and NGOs, on whom the bulk of refugee management falls, to make an extra information-gathering and coordination effort in order to offer the refugees sustainable solutions. In Spain, the Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security and Migration, in partnership with the La Caixa Foundation, has launched a programme for Spanish families wishing to take in Ukrainians, a public-private partnership mechanism that has never before been used to house refugees.

(2) An economic challenge both for the member states and for the EU

The housing of millions of Ukrainian refugees constitutes an economic cost to member states that is currently impossible to estimate, because of two fundamental uncertainties: how many people will ultimately leave Ukraine (5, 6, 8 million?) and how long will they remain in other countries? The answers to these questions depend in turn on the duration and course of the war in Ukraine, on the degree of destruction that the housing, infrastructure, services and businesses are subjected to during the conflict and the level of services and support offered by the European response itself.

The Dutch think tank Bruegel, using the costs incurred by Germany in 2016, has estimated an annual cost of around €10 billion for taking in a million refugees, which would translate into €50 billion for Europe this year if the final figure was 5 million people. The EU has already started to earmark funds to help member states take in refugees: €20 billion from the Cohesion Fund, the procedures of which have been modified to enable such expenditure, from the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund, and from the REACT-EU fund. This cost is in addition to the other economic impacts caused by the war in Europe, and come at a time when the EU is recovering from the crisis caused by the COVID-19 epidemic, with serious disruption to supply chains and with an urgent need to divert funding to the energy transition.

Furthermore, the funds spent by member states and the EU on housing Ukrainian refugees will have to be in addition to those needed for responding to asylum requests that will continue arriving from other parts of the world, predominantly Latin America in the case of Spain, and Africa and the Middle East in the EU as a whole.

(3) A challenge for integration

In this arena the uncertainties are even greater. In addition to the duration of the war and the number and pace of arrivals, there is the uncertainty of how many refugees will apply for asylum in the EU (a distinct legal concept from temporary protection) and will decide to remain permanently. Again, this depends on many factors that are currently unknowable. However, the experience of previous refugee crises in Europe and in general in the most developed countries suggest that a proportion of those fleeing war remain in the host countries on a permanent basis. This is more likely when entire families flee than, as in this case, the refugees are women with children, many of whom have left their husbands in Ukraine. The decision to return becomes more likely the shorter the time spent abroad, the closer the host country is and the smaller the difference between the welfare systems and, in general, between the quality of life in the original and the host countries. When conflicts drag on for years, the least likely return involves that of families with children educated in host countries.

The experience of Bosnian refugees in Canada is an example of the difficulties posed by going back: after the war in Bosnia (1992-95) came to an end, Canada launched a plan to encourage their return, paying for travel expenses and offering economic help for their reintegration in Bosnia, but only 30% of the Bosnians who had been granted refuge went back.

Two of the main difficulties with integration over the medium to long term are access to housing and work. These are both in short supply in many European societies and particularly in Spain, where people face specific difficulties in finding sufficiently stable and well-paid jobs and renting or buying housing. Compared to these two elements, the provision of other public goods such as access to healthcare and education for young people is relatively easy to achieve, although these too pose certain specific difficulties, such as the language of delivery in teaching and the low rate of COVID-19 vaccination in the Ukrainian population.

Access to jobs, which is allowed immediately under the Temporary Protection, will be particularly difficult for the women who have left Ukraine with small children, because in addition to the language difficulties there is the burden of their parental responsibilities. And given that women and children make up the bulk of the refugees (95%), this route towards integration, through employment, appears more difficult in the current wave. As far as housing is concerned, the situation differs from one EU country to the next, above all in terms of the size of the public housing stock. Spain is well known to have a paucity of public housing and the stock of private housing available to let is also meagre, with the consequence that this could become the main impediment to integration over the medium to long term, as it has already proved in the integration of the economic immigrants who entered the country since the end of the 1990s.

(4) Unanimous support for providing refuge

From the perspective of integration, this influx of refugees does however benefit from certain clear advantages compared to the circumstances present on other occasions: the first is the unequivocal and unanimous willingness of European states to provide refuge, evident in the invocation of the Temporary Protection Directive, endorsed by the 27 members. This decision by the political institutions reflects the state of opinion among the European public, overwhelmingly supportive of taking in Ukrainian refugees. No protests against this stance have been held in any European country, even by the xenophobic parties.

In this respect the current influx of refugees is exceptional: it has created no political fissures either within or between member states, a situation that contrasts starkly with the one that arose in the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ of 2015.

Meanwhile, such exceptional positivity draws attention to the difference in the reaction triggered by these refugees and the one caused by refugees reaching European soil from other parts of the world, principally the Middle East and Africa. Many have identified racism and islamophobia as the origin of this difference, especially when the focus is placed on the countries of Eastern Europe, the most reluctant in the EU to receiving immigrants from Asia and Africa, and especially opposed to Islamic immigration. This part of the EU, which was cut off from the West for more than 40 years (1947-89), had no experience during the Soviet era of immigration from other continents, of other ethnic groups or of other religions; by contrast, this was something that occurred in Western Europe from the 1960s onwards and, over the course of successive years, accustomed Western Europeans to living with people with different physical aspects, languages, religions and cultures. Eastern European countries remained ethnically and culturally homogeneous throughout these decades (with their own internal national minorities, which are not the product of recent immigration). The history of these countries, with borders that have changed frequently in recent centuries, often subjected to the wills of their dominant neighbours, divided and occupied in World War Two, later dominated by the Soviet Union, has bequeathed a legacy of insecure national identities that are anxious and fearful of being altered by factors such as the immigration of people with other ethnic and religious characteristics. Furthermore, since the attack on the Twin Towers in 2001 and the succession of terrorist attacks on European soil in subsequent years, Islamic immigration –whether seeking economic betterment or asylum– has been perceived in Eastern Europe as a factor of insecurity. Lastly, in those European countries that once formed part of the Ottoman Empire, Islam is viewed as a characteristic of the imperial power from which they were liberated.

Working in favour of the welcome given to Ukrainian refugees in Europe is physical proximity (social psychology and everyday experience suggest that people are more empathic towards neighbours than they are towards the geographically distant), the perception of cultural proximity to Ukrainian society and, most importantly, the way that Europeans identify with the cause of Ukrainian resistance to the Russian invasion. Unlike armed conflicts in other parts of the world, where the average European may often be ignorant or confused about the causes and course of development, Europeans in this case are in no doubt about how the conflict came about, or who is responsible for the war. Moreover, the invader, Vladimir Putin’s Russia, is perceived as a threat to our security, and the people who are fleeing are therefore welcome not only for being refugees but also because they are allies facing a shared threat. This connection is much weaker or non-existent in conflicts that cause the flight of refugees towards other countries or towards Europe from Asia and Africa. The demographic composition of the current refugee influx –comprising women and children– also makes it easier to accept.

Within the EU, the fact that it is the Eastern members that are this time bearing the brunt of refugee arrivals (rather than Southern Europe) has completely altered the political backdrop against which debates about the EU’s handling of refugees are held. For the time being, neither Poland nor any of the other countries of the East have requested that refugee distribution mechanisms be activated in order to alleviate the burdens they face, probably to a avoid a future situation in which, once this crisis has passed, the rest of the Union asks them to accept the resettlement of refugees arriving from other parts of the world. But it remains to be seen how this experience changes the way states position themselves on the overdue reforms of the European asylum system, which have been paralysed by lack of consensus. Similarly, it is doubtful whether the states’ own asylum systems, notwithstanding the aid sent from Brussels, will maintain their capacity for taking in non-Ukrainian refugees in the same numbers while simultaneously attending to the needs of Ukrainians.

Conclusions

In the midst of radical uncertainty about the duration and demographic effect of the war in Ukraine, it is impossible to forecast what impact the arrival of millions of Ukrainians may have on the EU host countries. The EU itself, its member states and national populations have reacted with unprecedented speed and generosity, characterised by a mass mobilisation of private and public initiatives, the triggering for the first time of the Temporary Protection Directive (approved in 2001) and with European reserve funds to help states cope with their refugee programmes. This has all unfolded amidst a practically unanimous consensus and acceptance of the Ukrainian refugees.

In the short term their reception poses a challenge of coordination between the public and private initiatives, while challenges in a variety of areas emerge over the medium to long term. The first involves the integration of the new arrivals (appropriate adjustment of the education system, access to housing and employment), and the second involves the availability of the organisational, administrative and financial resources assigned to these and other refugees. It is necessary to prevent this crisis from monopolising the capacities available, which were already scant, in order to attend to the needs of those fleeing conflicts in other parts of the world.

*About the author: Carmen González Enríquez is Senior Analyst at the Elcano Royal Institute, where she heads the Migrations and Public Opinion areas. She is also a Full Professor in the Department of Political Science at the UNED.

Source: This article was published by Elcano Royal Institute