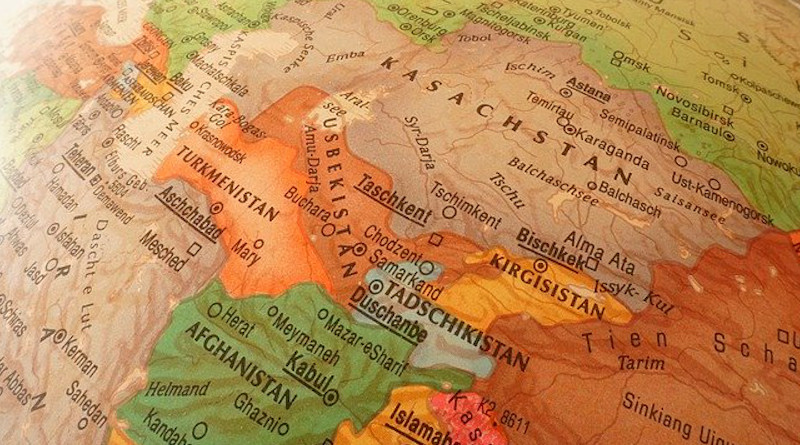

Russia-Ukraine War To Change Central Asia’s Trade And Transition – Analysis

By James Durso

The Russia-Ukraine war is upending global supply chains.

In the case of Central Asia (the five republics plus Afghanistan) this impact reinforces the need for redundant transport routes and options for the landlocked states of Central Asia. These states still rely on Soviet-era transport links that connect them to markets. This remains true even though during the three decades since independence in 1991 have seen new roads, railways, and pipeline put in place, many funded by China.

The need for more options was evident before the war, and leaders in the regions took action to diversify the region’s economic options.

In July 2021 Uzbekistan hosted a conference on connecting Central Asia and South Asia, and has prioritized transport through Pakistan to the ports of Gwadar and Karachi over routes through Iran to the port of Bandar Abbas. Later that month, Pakistan and Uzbekistan signed a transit trade agreement that “would give access of Pakistani seaports to Uzbekistan and offer access to all five Central Asian States for Pakistani exports.”

In August 2021, Tashkent pivoted and signed 98 trade and investment agreements with Delhi that may yield up to $2.3 billion.

In January 2022, India’s president, Narendra Modi, hosted a virtual India-Central Asia summit with the presidents of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. The conference covered trade and connectivity issues, cultural exchanges, and security cooperation, among others, and followed the December 2021 signing of nine agreements in areas such as renewable energy, digital technologies, cyber security, and community development projects.

Some routes for the region’s trade are:

(1) East to China via the mooted China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan corridor/rail line, which may divert traffic from a Russian route. Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoev noted in May that the line will “open new opportunities for transport corridors linking our region with markets in the Pacific Ocean area. The move will add to the widening of existing railway routes connecting East with West.”

(2) West from Afghanistan to Turkey via Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan and Georgia via the “Lapis Lazuli Corridor.”)

(3) West to Turkey via the Zangezur corridor through Armenia, though the ongoing dispute between Azerbaijan and Armenia will cause a lengthy delay.

(4) The East-West rail line from China to Turkey, the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, also known as the “Middle Corridor,” which circumvents Russia and is used by Kazakhstan to export petrochemical products, metals, coal, grain, oilseeds, and other agricultural products. The route, which hasn’t yet lived up to its potential may finally get a chance to flex and was on the agenda in a recent meeting between the leaders of Turkey and Kazakhstan. In April, shipping company Maersk announced revamped rail service “in response to customers’ ever-changing supply chain needs in the current extraordinary times,” and commissioned the new service with a 13 April train from Xi’an, China to Germany.

But what about the overland access to the major seaports of Karachi, Gwadar, and Chabahar, and access to the big markets of Iran (84 million people), Pakistan (225 million people), and India (1.4 billion people)?

That Uzbek-Pakistani transit trade agreement will only work if Afghanistan is a safe trade space, and the Central Asians will have easy access to India if they can use the port of Chabahar in Iran.

To execute the July 2021 transit agreement, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan have agreed to a (yet unfunded) roadmap for railway construction that, if realized, will reduce shipment times from Uzbekistan to Pakistan from 30 days to 10, and reduce transport costs from central Asia to Pakistan by 30%.

Unfortunately, projects like this may be blocked by sanctions on the governments in Kabul and Tehran.

America’s war with Iran goes back to the Iranian Revolution in 1979, which ejected its client, the Shah of Iran. Washington has sanctioned the clerical regime on a regular basis ever since, and successfully increased sanctions as Iran made advancements in its nuclear and missile programs, forcing the regime to negotiate the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.

The U.S. suppressed the Taliban government in Kabul via sanctions on the organization and on the majority of individuals who make up the caretaker government, and will maintain them to force a government more to the liking of the West (which is also the intent of Iran sanctions.) Ambitious projects in Iran may be endangered as up to a third of the economy is believed to be controlled by the sanctioned Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

The U.S. strategic goals for Central Asia include sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity, so Washington should work to see those goals realized, even it means the Central Asians will be trading with, and via, Kabul and Tehran.

Unfortunately, U.S. and NATO humiliation and anger over defeat in Afghanistan may be blinding Washington and Brussels to the lingering impact on the region of the failed intervention, and that the region can start to recover, but only if it can grow economies and create opportunity for the large, young populations.

If the U.S. and Europe want to free the region from the gravitational pull of Russia and China, they will have to decide on their priorities – satisfying punishment meted out to Iran and Afghanistan, or economic opportunity that will reduce migration for work and ease tension with neighbors; keep families together; reduce reliance on remittances from guest workers, which gives Russia leverage with the republics; reduce the need for foreign aid; and keep extremism at bay.

But with trade will come increased narcotics trafficking (which is trade, after all) from Afghanistan, the leading source of opium poppy (and which boosted production by almost 40 percent in 2020) and a growing producer of methamphetamine. The region will require assistance from the U.S. and Europe (where most of the drug buyers are) and specialists at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime to counter smuggling. And it may also open the door for U.S. and European cooperation with Iranian law enforcement agencies as Iran is a major transit corridor for Afghan poppy, and is itself dealing with a significant drug addiction problem.

Narcos are just transport guys who haul drugs, but also weapons, humans, gem stones, hardwood, metals, antiquities, stolen art, stolen cars, and rare animal species. U.S. weapons abandoned in Afghanistan, reportedly $7 billion worth, will enter the international trade stream (they are already for sale locally), so it would be good if the West helped the locals stanch this trade. And legitimate economic activity caused by new trade routes will also create opportunity for farmers, traders, and transport companies to avoid involvement in the drugs trade.

Special attention should be given to Tajikistan, a drug trafficking corridor with a flag, where the transit traffic is equivalent to 30% of the country’s GDP. The country is also a close ally of Iran, which recently commissioned a drone assembly line in Dushanbe, so the West will have to deploy its best diplomats and economists as it works to displace illicit income without destabilizing the economy and society, and without giving Iran an excuse to create a new member of the “Axis of Resistance” (Pamirs Division).

The Russia-Ukraine war is an opportunity for Central Asia to put some distance between itself and Russia. It is not interested in an antagonistic relationship with Moscow, it just wants some space and options.

Nor does it want to be a platform for NATO’s proxy war against Russia, especially if Washington is in one of its “you’re either with us or against us” moods.

Russian trade and investment will fall as a result of Western sanctions, and the republics have refused to endorse the Russian incursion into Ukraine. At the same time, China may decide to take a greater role in the region as a result of NATO’s retreat from Afghanistan, but it hasn’t made any overt moves, other than a military base in Tajikistan.

In this gap between Russia and China is an opportunity for the five republics to form a regional community to solve regional security and infrastructure issues, such as the need for the southern corridors to the sea. The projects will require cash and political support that the region can successfully solicit if it makes its presentation as a bloc.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative has pumped about $40 billion into the region, but recent surveys by the Central Asia Barometer showed “a significant decrease in public sentiment towards China is present, particularly regarding those who reportedly viewed China as ‘somewhat favorable.”

This is happening even as China seeks gains in government-to-government fora such as the China + Central Asia Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in May 2021.

Added to that Russia’s weak presence in future years and this is a potential opening for the U.S., Europe, and other partners like India, Japan and South Korea, to build solid relations in the region, if they can just clear the way for all the countries in the region to develop trade routes to all points of the compass without fear or hindrance.

This article was also published at Defense.info