The Mighty Dollar: Questioning The Role Of A Monetary Hegemon – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By Diya Dixit*

Over its 70-year reign, the dollar has secured for itself a role that far outsizes its parent nation. The United States (US) accounts for just over a tenth of global trade and contributes about 24 percent in GDP to the world economy. The dollar, however, is involved in almost 90 percent of global foreign exchange transactions, accounts for 59 percent of forex reserves held by central banks and is the currency of choice for invoicing about 50 percent of world trade.

Undoubtedly, much of globalisation took place on the back of the dollar, and its use in trade and finance provided surety and ensured convenience. However, in an increasingly multipolar world, with the rising economic prowess of the Global South, the costs and benefits of a dominant currency regime must be reassessed.

Stifled gains and rising threats

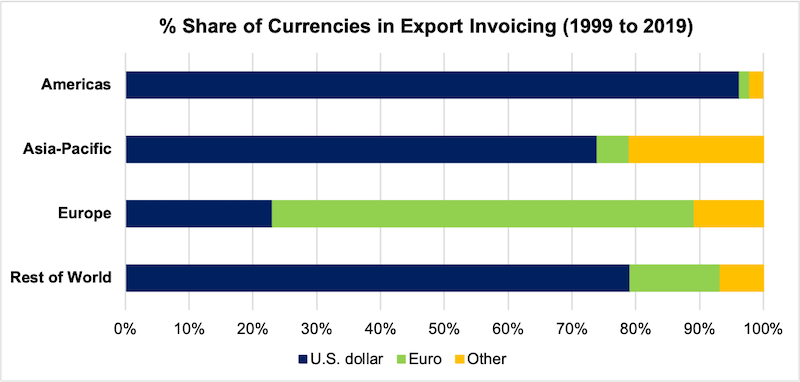

While the dollar-led international monetary system has morphed over the years to accommodate the changing dynamics of globalisation, it continues to feed a cycle of inter-country inequality and amplifies business cycle fluctuations in developing and emerging economies. Particularly during times of monetary tightening, currency values collapse against the greenback and capital flees emerging economies’ shores. As a nation’s currency depreciates, standard economic thinking, very optimistically, indicates that although import costs rise, exports become relatively cheaper in the international market, increasing demand from foreign purchasers and boosting domestic growth. Unfortunately, this conclusion rests on the assumption that traders set prices in the exporter’s currency. In reality, a majority of international trade is invoiced in a dominant currency—most commonly the US dollar.

Particularly true for emerging markets and developing economies, where pricing in dollars is more prevalent as compared to advanced economies, currency depreciation fails to make exports cheaper for foreign buyers, resulting in no incentive for them to increase demand. In the short run, therefore, exports do not receive a boost and domestic economies are further crippled by expensive imports, a phenomenon experienced by most of the Global South after the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates in 2022. In effect, this mutes a primary advantage of the flexible exchange rate regime, and gains to be made on the export side during a currency depreciation are lost.

The US also wields significant financial firepower in the form of sanctions and restrictions on the use of the dollar. For instance, in the recent wave of sanctions against Russia, the US and its allies froze almost half of the Russian central bank’s foreign exchange reserves and barred major Russian banks from using the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications (SWIFT)—an interbank messaging system that facilitates cross-border transactions. The threat of losing the ability to do business in an interconnected world has further pushed countries to consider a shift from the dollar, as well as develop alternatives to US-controlled clearing and communication systems like the Clearing House Interbank Payments System (CHIPS) and SWIFT.

With great power, comes great responsibility

For the US, controlling the world’s reserve currency means that it can borrow cheaply from around the world to fund a lifestyle beyond its means. Some groups of Americans, however, are not revelling in the dominance of the mighty dollar. While Wall Street and military establishments may have gained from the rule of the greenback, manufacturing and export-driven sectors have paid the price. High demand for the dollar all over the globe increases its value, making US exports relatively expensive. This, in turn, hurts sectors like manufacturing in areas such as the Rust Belt, where workers have been laid off and jobs offshored.

This angst about inequality has further heightened divisions in US politics, with right-wing politicians advocating trade deficit reduction and the adoption of more inward-looking policies. A large move towards such policies, however, would mean weighing the advantages of wielding significant financial power, the benefits of attracting capital from around the world and profits to be made on Wall Street, against the disadvantages of deindustrialisation. For the US, it is likely that the former will continue to outweigh the latter.

Winds of change

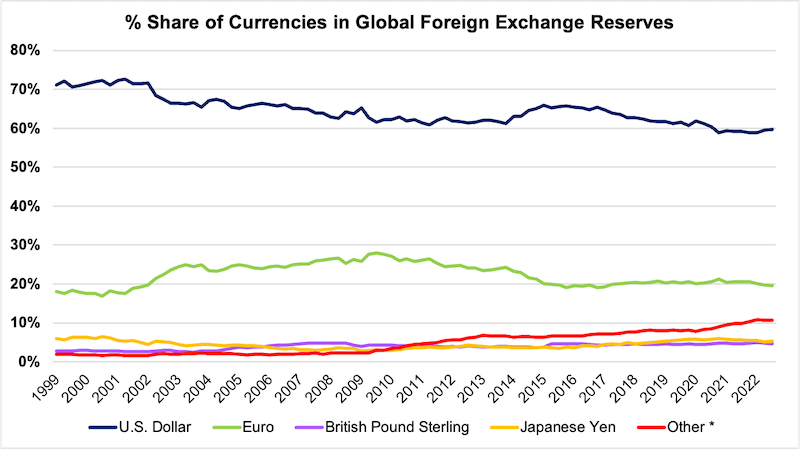

The dollar’s role has seen some change recently, albeit small. For instance, the share of foreign exchange reserves held in US dollars by central banks around the world has fallen from 71 percent in 1999 to 59 percent in 2021. This fall in the share of the dollar has been accompanied by an active diversification of central banks’ forex portfolios across the globe towards non-traditional reserve currencies, with historically dominant reserve currencies like the Euro, British Pound, and Japanese Yen taking a comparative back seat. A major attraction for central banks has been the rise in scale and liquidity of markets in smaller economies, coupled with comparatively higher returns when adjusted for volatility.

* “Other” category includes the Australian dollar, the Canadian dollar, the Chinese renminbi, the Swiss franc and other currencies not separately identified in the COFER survey. China is a COFER reporter since 2017.

The development of deep, liquid, and open domestic-currency asset markets across countries, together with electronic trading platforms and automated market making, has reduced the costs of trading directly in domestic currencies. In fact, emerging economies’ contribution to global trade and capital market transactions has steadily risen, and transactions in emerging market currencies presently account for 25 percent of global foreign exchange turnover, up from just 7 percent in 2001.

Increased use of local currency settlement (LCS) arrangements between Asian economies, allowing countries to settle international transactions in trade and investment in local currencies, was advocated by Indonesia during its G20 presidency in 2022. LCS agreements have the capacity to reduce the spill over effects of monetary tightening in advanced economies, reduce dependence on the whims of the dollar, and limit vulnerability to financial instability caused by global shocks. India, too, recently allowed the invoicing, payment, and settlement of trade in rupees, while also exploring bilateral pacts, similar to the rupee-rouble agreement, with South Asian countries.

Additionally, the BRICS—a multilateral grouping consisting of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa—declared the development of a reserve currency, comprising a basket of member nations’ currencies. Although the idea of a BRICS reserve currency rests on shaky ground, given the inherent heterogeneities and strategic conflicts within the group, increased bilateral trade in domestic currencies between member nations could pave the way for diversification away from the dollar. Moreover, with oil exporters like Saudi Arabia keen to forge stronger ties with emerging and developing economies, domestic currencies could also inch their way into the oil trade.

A multipolar future

While geopolitical gears are certainly shifting, it would be naïve to declare the demise of the dollar just yet. Historically, no single currency has been successful in dethroning the greenback. The euro failed despite being pitched by an economy comparable to the US in size, and the newer contender, the Chinese renminbi, is unlikely to be backed by markets flexible and transparent enough for it to rule.

Consequently, a slow, but steady move towards a multipolar currency regime is likely. Large network effects, historical anchors and the simple advantage of incumbency implies that the shift away from the dollar will be slow, and must be accompanied by multilateral cooperation. A subtle but distinct shift away from the dollar is certainly underway. A shift that has the potential to rebalance the international system of trade and finance in an equitable way, with the emerging and developing world establishing itself as a force to be reckoned with.

*About the author: Diya Dixit is an intern with the Centre for Economy and Growth at the Observer Research Foundation

Source: This article was published by the Observer Research Foundation