Belarus Presidential Elections: A Change In The Offing? – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By Pritish Gupta*

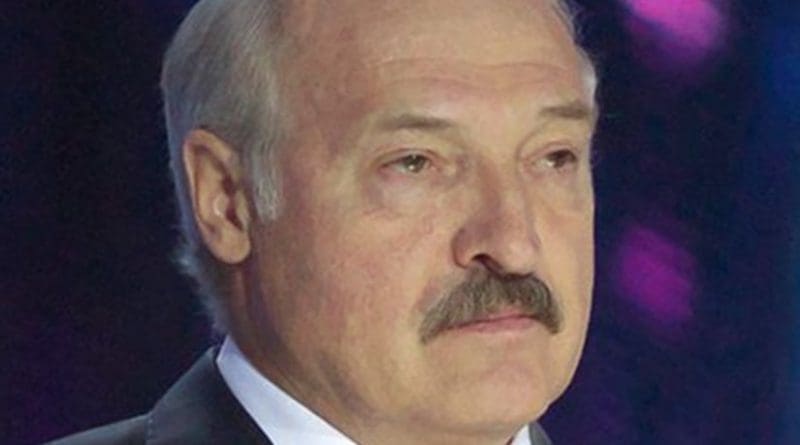

Belarus is set to hold presidential elections this month and President Alexander Lukashenko is seeking a sixth term in office. Lukashenko has been in power since 1994 and is expected to win the election but not without difficulty.

Lukashenko’s opponents have mounted a strong election campaign and are receiving quite a bit of popular support. The protests against the regime and in support of the opposition continue to gather momentum across Belarus, despite the pre-election crackdown on the opposition.

What complicates matters for Lukashenko is that the elections are taking place at a time when the economy is weakening and public discontent is growing with the government’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic. Even substantial number of the elite in the country are disillusioned with the current government, according to some reports. Official figures put Lukashenko’s approval ratings at about one-third of the population, but independent observers say it is half that number.

The election campaign

The unexpected rise of new candidates in the election campaign is remarkable and indicative of the spread of anti-Lukashenko sentiments. The Belarus Central Election Commission has registered five candidates for the presidential poll. A candidate needs to collect at least 100,000 signatures to register for the elections. Compared to the previous elections, the enthusiasm about the election among the Belarusians is unprecedented.

Apart from Lukashenko, the Election Commission recognises Andreij Dmitrijev, social activist and co-Chairman of the Speak the Truth movement, Anna Kanopackaja, a lawyer and former MP, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, a language teacher and Sergeij Cherechnia, chairman of Belarus’ Social Democratic Party, as candidates in the election. This scenario — multiplicity of candidates — should help Lukashenko triumph despite the erosion of public support.

Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, wife of Sergei Tikhanovsky, the YouTube vlogger, is standing in his place because the Election Commission barred him after detention for alleged violation of public order at one of his rallies. Tikhnovskaya has unexpectedly emerged as the main challenger to Lukashenko after several opposition leaders including some who were disqualified from contesting, announced their support. On Thursday, a huge rally took place in Minsk in her support. This would worry Lukashenko and some observers expect it will not pass unchallenged by the incumbent.

Earlier, the Belarus Central Commission refused to register the two main opponents as candidates in the presidential elections. Mr. Viktor Babaryko, a former banker who headed the Belgazprombank was considered the main rival of Lukashenko. Babaryko gathered more than 400,000 signatures in support of his candidacy. In June, he was arrested on the charges of embezzlement and fraud, effectively barring him from running in the election. The commission stated that Babaryko’s candidacy has been rejected due to undisclosed income and foreign funding for his campaign. Mr. Valery Tsepkalo, a former ambassador to the US, who was also seen as a potential opponent, was barred for allegedly lacking valid endorsement signatures. Tsepkalo submitted 160,000 signatures but only 75,249 were accepted.

Both the candidates criticised the ruling by the election commission as ‘politically motivated’. The European Union also called the decision to debar the two candidates as “seemingly arbitrary.” Violent protests erupted across Belarus against the exclusion of the two significant candidates from the forthcoming elections. Over 250 people were detained during the protests in major cities, with some facing serious criminal charges.

The crackdown on dissidents and political opponents is not a surprise in Belarus under the authoritarian rule, but this time the detention of journalists and peaceful protesters started way back in May, with over 650 of them held up for staging protests against Lukashenko. The President also dismissed his cabinet two months before the scheduled elections. Due to dismal ratings of the incumbent, the government banned the online polls and surveys as well.

However, a pre-election crackdown on opponents is likely to hurt Lukashenko’s efforts to mend ties with the West. A joint statement was issued by the diplomatic missions in Minsk that urged the Belarusian authorities to take the requisite measures to hold free and fair elections. The Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), an international election monitor, has not recognised any elections in Belarus as free and fair since 1995. It would not monitor the upcoming Presidential election as well, citing lack of timely invitation.

Thus, Lukashenko’s gradual rapprochement with the West may face turbulence in wake of the clampdown on political dissent. This could result in the opposite of what he had hoped for when he reached out to the West. It would leave Belarus dependent on Moscow with little room to reopen the diplomatic channels with the West.

Lukashenko’s position

Alexander Lukashenko is facing resentment lately due to number of factors. His decision to completely disregard the coronavirus pandemic has rebounded badly. The dismissive response was coupled with frivolity where the President suggested that Belarusians take tractor rides, work more and drink vodka to stay healthy amid the crisis. The official virus-related death figures are also under question, further eroding the credibility of the government. The Belarusians compare the suppression of information on the pandemic in the country to the way the Soviet authorities treated the Chernobyl disaster.

Also, the Belarusian economy is crippled as a result of the Covid-19 global economic slowdown. The economy is expected to shrink close to 4% this year as per the World Bank forecasts. The country’s GDP remains unchanged since 2010 with public debt mounting at an increased rate, leaving the Belarusians dissatisfied with the Lukashenko government. Lack of economic reforms has deepened the crisis.

Moscow’s increasing pressure on Minsk to move towards deeper integration, drove large scale rallies and protests, encouraging the political opponents to voice the need for change of leadership.

Fraying relations with Russia

Belarus’ tilt away from Moscow became prominent after the oil dispute arose between the two countries late last year along with Lukashenko’s reluctance to push for a Union State. Signed by the heads of states in 1999, the Agreement on Establishment of the Union State of Belarus and Russia sets up a legal basis for integration between the two countries. The agreement calls for cooperation on foreign policy, defence and economic policies with an aim of setting up a unified parliament and a single currency in the future. However, as Moscow pushed for integration talks towards the creation of a single state, Lukashenko affirmed to protect his country’s sovereignty. This has strained the bilateral relationship, diminishing hopes of a full implementation of the agreement and leading to a trust deficit.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s visit to Minsk in February appeared to signal normalisation of relations with the US. The US also nominated its first ambassador to Belarus in more than a decade. Also, Belarus ordered its first shipment of oil from the US in May, showcasing its willingness to test ties with Russia and diversifying its diplomatic relations.

Indirectly, Lukashenko also accused Russia of meddling in the presidential election citing external forces working with his opponents, though Kremlin has denied the allegations. Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov stated that Russia has no intentions to interfere in the election process.

In a recent development, the authorities in Belarus arrested 33 Russian mercenaries over an alleged plot to destabilise the situation in the country before the presidential elections. Moscow has dismissed the claims and asked for an explanation from Belarus.

The social contract

The new wave of opposition has certainly unsettled Lukashenko and brought into question his political grip over the country. But he still retains support of a sizeable chunk of ordinary Belarusians, who do not want to see their country face the turmoil that tore apart their neighbour — Ukraine. Regardless of the outcome of the election, Lukashenko’s social contract with the people — offering loyalty in exchange for economic prosperity, is in tatters. Nevertheless, the disgruntled electorate’s desire for a post-Lukashenko democratic Belarus may not be attained this August.

*The author is a research intern at ORF.