Quad: A Mini-NATO In Disarray – OpEd

By B.M. Jain*

Does the Quad not remind us of the classic Cold War between America and the Soviet Union in the 20th century? Both were determined to outdo one another in pursuit of their narrow geopolitical interests. The Cold War ended with a bizarre outcome with America’s emergence as a sole global superpower, bringing in its trail chaos, instability, and bloodshed through mindless military interventions— for instance in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and many other conflict–ridden zones across the globe. Apparently, the Quad is assuming the shape of a 21st century Cold War between America and China. The latter has replaced Russia in the power configuration. But there are two distinctively emerging security alliances. The one is led by America and joined by Japan, India, and Australia. And another is led by China, and likely to be joined by Russia and North Korea as its strategic partners if the US-led security alliance poses an existential threat to them. In principle, the Quad has laid down its goal of realizing a “free and open” Indo-Pacific region under the US captaincy. Its purported aim is to restrict China’s expanding geostrategic foothold in the region by projecting the latter’s “aggressive behavior.” It also aims to transform Quad into strong and stable security architecture in the Indo-Pacific region to defeat China’s aggressive geostrategic moves.

The fundamental question arises whether there is coherence of goals and interest among Quad members. A commonality is that there is a catalogue of complaints against China, shared by all the Quad members. For instance, the Biden administration has already defined the US foreign policy in terms of “competition” with China, which alone is capable of challenging America’s so-called hegemony. India is in the company of Quad mainly because of its persistent border clashes with China as well as the latter’s strategic encirclement of India in South Asia with Beijing’s expanding geostrategic foothold in the Indian Ocean. Therefore, India perceives its strategic partnership with America, Japan and Australia as an imperative to thwart China’s challenge. This is evident from their multilateral joint naval exercises being conducted beyond the shores of the Malabar Hill with a clear objective of defending India’s economic and strategic interests in the Indian Ocean.

As regards Australia, it is on a collision course with China on trade and security issues, including Canberra’s demand for holding Beijing responsible for the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. From the geopsychological point of view, Australia feels much threatened by China since it does not have naval and nuclear capabilities to resist China’s strategic onslaught. In other words, Australia’s serious security concerns have obliged it to join the Quad. So far Japan is concerned, Beijing has not forgotten its historic rivalry with Tokyo that dates back to the Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945). The war scars are still deeply etched in the Chinese geopsychology. President Xi Jinping demanded that Japan should tender unqualified public apology for its historical atrocities against China, though Tokyo refused to oblige Beijing.

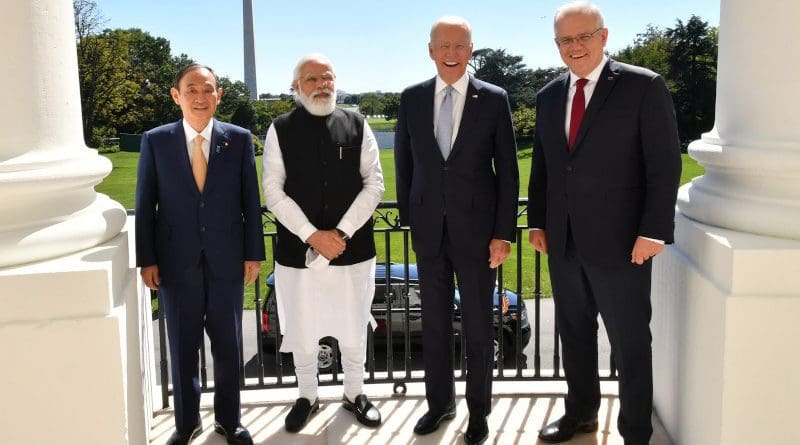

If viewed from an array of divergent interests among Quad members, there is a lack of clarity and congruence among them on developing a sound and inclusive security architecture to deal with China—their common adversary. The Quad Summit held in Washington on September 24th discussed a plethora of issues, including the South China Sea, climate crisis and cyberspace, but it focused on the imperative of cooperative approach to promote a “free and open” Indo-Pacific with a view to countering China’s attempts to subvert the status quo in the region.

Ironically, with the launch of AUKUS, a military alliance aimed at building Australia’s naval sinews to checkmate China’s assertive postures, it is likely to cause ripples between America and its EU partners like France. It is quite intriguing that Australia’s cancellation of a multibillion-dollar nuclear submarine deal with France soon after the inauguration of AUKUS invited deep wrath in France’s corridors of power. As reported, the angry French foreign minister reacted sharply, saying “This brutal and unilateral decision resembles a lot of what Trump is doing.” It should be borne in mind that France has its legitimate strategic stakes in the Indo-Pacific region. This apart, the decision of America and Great Britain to develop a nuclear-powered submarine fleet for Australia, including transfer of US Tomahawk cruise missiles, might further accelerate the chances of opening a new theatre of warmongering between China and the US-led Quad. The more the provocative acts the US and its allies engage in against China, the more aggressive and revengeful it will become. Therefore, it warrants that great powers avoid the simmering confrontation with China through pro-active diplomacy in larger interests of the global and regional peace and security.

*B.M. Jain, Professor of Political Science and International Relations. Former visiting professor, CSU, Ohio, SUNY at Binghamton, NY, and UBC, Canada. Author of: “The Geopsychology Theory of International Relations in the 21st Century” (Lexington Books, Lanham,MD,2021) and “China’s Soft Power Diplomacy in South Asia” (Lexington Books, 2017).