The UNHRC Resolution And Implications For Sri Lanka – Analysis

By IDN

By Dr Palitha Kohona*

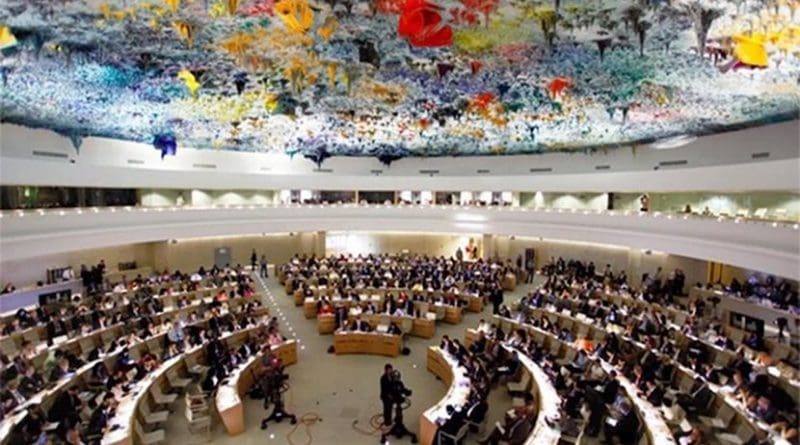

The UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) adopted the resolution entitled “Promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka” on October 1, 2015, Resolution 30/1. This has been described by some critics as a constitution amendment project for Sri Lanka. Interestingly, it was cosponsored by Sri Lanka. In 2017, Sri Lanka obtained a two-year grace period to implement the resolution, further confirming the country’s acquiescence with Resolution 30/1.

Ominously, this year, the High Commissioner commented that in the absence of progress on the implementation of Res. 30/1, other countries could invoke the “universal jurisdiction” principle to start judicial proceedings against persons accused of having committed war crimes.

This quantitative leap in the approach of the normally circumspect and erudite High Commissioner has caused more than a few eyebrows to be raised. Special Mandate Holder, Ben Emerson, went way beyond his brief when he threatened dire consequences for Sri Lanka not vigorously implementing the resolution. We have reached the end of another Human Rights Council (HRC) Session. Sri Lankan NGOs took centre stage at this session.

Prior to 2015, the HRC had adopted three resolutions critical of Sri Lanka since 2012 with every year witnessing a diminishing number of votes in support of Sri Lanka and a gradual tightening of the provisions in the resolutions. Interestingly, with the change of government, Sri Lanka decided to cosponsor the 2015 resolution.

The key objective of the new government in cosponsoring the resolution appears to be to accommodate the concerns of its main sponsors (mainly some key Western counties) and appease them with a view to ending the increasingly bitter confrontation that was developing between them on the one side and Sri Lanka on the other. Perhaps, the Government even expected to be rewarded with large dollops of aid money from the West. (The new administration in Washington has reduced the small amount of aid funding provided to Sri Lanka, $35 million, to a measly $3.4 million).

Earlier with the gradual deterioration of key bilateral relationships, and the slow motion drift away from each other, the U.S. began to take the lead in driving the resolution critical of Sri Lanka in 2012 at the HRC. A country that was once considered a warm friend of Sri Lanka was now acting in an outright hostile manner. The U.S. military had even shared vital intel with the Sri Lankan military during the critical last stages of the war although other parts of the administration, with the Leahy Act providing the inspiration, were taking an increasingly hostile attitude.

The U.S. lead was followed by the UK and Canada, with the EU joining in. The result was inevitable. The U.S., with diplomatic missions in a majority of countries of the world and far reaching economic and military clout, had the type of diplomatic influence that could overpower many challengers. Even friends such as India, a stalwart of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), advised Sri Lanka to reach an accommodation with the West.

Unfortunately, Sri Lanka, for reasons that cannot be explained in a few words, decided to confront the U.S. at the HRC and to oppose the resolution. Sri Lanka just did not have the diplomatic and financial muscle to take on the U.S. head on. The U.S. was able to ensure that India, despite its long standing proximate relationship with Sri Lanka, joined those who would vote against us in 2014.

And Sri Lanka, by far, was not even the worst offender to incur the wrath of the international human rights lobby groups and the leading Western human rights champions. However, once the decision was made in Colombo to confront the U.S., the diplomats gamely spearheaded Sri Lanka’s campaign, including in New York.

Unfortunately, the U.S. position continued to harden and Sri Lanka was getting pushed in to the same basket of usual suspects reserved for the states regularly black listed by Washington. E.g. North Korea, Burma, Iran, Belarus and Syria. This was an unfortunate development in the bilateral relationship.

Could this change in the relationship be explained in a simple manner? Much more research will need to be done. In my mind one thing was clear. It was not only the possibility that the Sri Lankan forces may have committed human rights violations that drove Washington to spearhead a campaign to demonise Sri Lanka and its leadership. There were other more likely candidates for this demonic label of “really nasty state”. In my view there were political and personal goals and prejudices at play as well. Some have even suggested that this was part of a regime change project.

The three human rights champions of Washington, all women, (Power, Rice, Donoghue) may have decided to pick on Sri Lanka for their own reasons. Iraq, Afghanistan and, definitely, Israel were “No Go” areas for any American official with ambition. Iran and Syria were a waste of time because the countries concerned were in the habit of ignoring Washington’s agonised and vitriolic complaints about human rights violations.

Sri Lanka was always in the limelight, thanks to an array of human rights organisations that targeted the country regularly and a good candidate to be dragged over the coals. The media could not get enough of the bad side of Sri Lanka. UK’s Channel 4 made it a habit of producing a heart-wrenching documentary on Sri Lanka’s war on terrorism from an anti-government perspective annually and, intriguingly, prior to the l sessions. Channel 4 seemed to popularise the view that Sri Lanka was the nastiest of them all, largely based on allegations, which have been challenged by Sri Lanka. Reich Minister of Propaganda of Nazi Germany, Joseph Goebbles, once said that a lie repeated often enough would become the truth. This was happening in the case of Sri Lanka.

In addition, prominent elements of the Sri Lankan leadership glowed in the light of Western approbation. The elements behind the resolution may have figured out that denying them the approbation that was so eagerly sought, was a punishment by itself.

Most importantly, Sri Lanka seemed to take the bait and respond as expected. Was it was more like a game?

Personal confrontations and prejudices most certainly encouraged powerful individuals in the West to strive for the kill in Sri Lanka. There is no doubt that personal relations are a major part of diplomacy.

Sri Lanka, for its part, may not have adequately addressed some of the allegations or orchestrated its message contradicting the Channel 4 documentaries, the media stories and the perceptions that were mounting. There was considerable opportunity to do so without appearing to toe the Human Rights Council line. Sometimes we may have missed the trees for the woods.

But these opportunities were not used, ignored or simply dismissed. Significantly, well-resourced LTTE support groups kept up the anti Sri Lanka campaign using influential members of the Western political establishment, the NGO community and the media. Yasmin Sooka, a member of the Secretary General’s personal Panel of Experts, has continued to highlight absurd numbers of civilian deaths with no substantiation. She has even made the outrageous suggestion that the government deliberately starved the civilians. You will recall that Hilary Clinton received funding from the group, “Tamils for Hillary” which was affiliated with the LTTE while the LTTE was a proscribed foreign terrorist organisation in the U.S. Later the campaign was obliged to return the contribution after we made representations at the highest level. That did not stop Hilary Clinton from subsequently talking about bad terrorists and good freedom fighters.

The possibility of orchestrating a regime change may also have entered the minds of the powerful in the West. The UNHRC provided a useful platform to enhance the negative image of Sri Lanka.

What are the consequences of cosponsoring the resolution for Sri Lanka?

First, it must be remembered that a resolution of the Human Rights Council is not binding. There is no obligation on the part of the target country to give effect to such a resolution.

A Human Rights Council resolution is binding on the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and his Secretariat but not on Member States of the UN. One must remember that even a resolution of the UN General Assembly is not binding. The freedom of action of the High Commissioner pursuant to a Council resolution is limited by what the target country would allow him to do within its jurisdiction. The impotence of the High Commissioner has been demonstrated, in a practical sense, time and time again, by countries, which were targets of Council resolutions. Iran, Israel, Belorussia, Syria, et al have had many resolutions adopted against them. And they happily ignore these. There are many such resolutions and reports produced by the High Commissioner which are gathering dust in the Secretariat simply because the target countries have refused to cooperate.

Are there possible consequences for non-compliance with a Council resolution? The Council is not empowered to impose penalties on a recalcitrant state, but the matter of a serious and persistent violator of human rights could be raised at an appropriate UN agency with punitive powers, such as the UN Security Council.

Given the political nature of the Security Council, it takes considerable effort to get approval for any sanctions initiative, even if the other requirements of the Charter are satisfied. Those with powerful friends are always shielded at the Security Council. It will also not set a precedent that could make lives difficult for its members. It was not without reason that the West did not bring the matter of alleged Sri Lankan violations of global human rights standards before the UN Security Council.

The option of bilateral measures against Sri Lanka was always a possibility and due to their political nature, they were not dependent on HRC resolutions. The EU suspended Sri Lanka’s GSP Plus concession before there was any action adopted by the HRC. Similarly, Washington suspended the Millennium Challenge Account with no sight of any HRC action against Sri lanka.

It could legitimately be asked whether the Council exceeded its mandate in adopting the resolution in its final form. The Council was established by the UN GA to assist countries to improve their human rights standards. Not to drag them over the coals in a targeted manner for alleged violations of global human rights standards. Certainly, political victimisation was not one of the objectives of establishing the HRC. The Council has been overly politicised and it has been severely criticised for its selective application of global standards mainly to non-European countries.

Sri Lanka decided to cosponsor the 2015 resolution. This, while not creating a legal obligation, certainly creates at least a powerful moral obligation to implement its provisions. But moral obligations in the international arena belong to a grey area. Many states would interpret moral obligations to suit their own circumstances. Others would give effect to them in bits and pieces. Yet others would simply let them drift into history. Having said that, one could argue that a country’s credibility would depend on complying with obligations it has voluntarily undertaken. In the international arena, it is not advisable to walk away from voluntarily adopted obligations, especially for a small country.

It is possible that a country which is not obliged to comply with a resolution, to be talked in to complying. We note that a range of international players, including Prince Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, the High Commissioner for Human Rights and Ben Emerson, the Special Mandate Holder, Alice Wells, Assistant Secretary of State, and even the U.S. Ambassador in Colombo, Atul Keshap, are doing exactly that.

Or it could convince itself in to complying. This may also be happening in Sri Lanka today. Egged on by the West dependent NGO community, the government appears to be bending over backwards to comply with the resolution, occasionally stopping to worry about the gathering public criticism, although the President and the Prime Minister, both, have said that there will be no foreign judges in the tribunals to investigate allegations against military personnel.

The President has further said that war heroes will not be allowed to be dragged before international tribunals. It would have been so much more sensible to have inserted a suitable qualification to the resolution at the time of cosponsoring. The struggle to qualify the resolution under domestic pressure, post facto, does our international image no good.

A stream of Western dignitaries and the UN Secretary-General have visited the country and have given copious advice on the value of complying with the Human Rights Council resolution. Some would say that considerable pressure has been applied on Sri Lanka. They have included the former Secretary of State, John Kerry. The former UN Secretary-General, having resisted visiting Sri Lanka since the end of the conflict during the Rajapaksa presidency, decided to drop in with only four months left of his tenure of office, perhaps to add weight to the efforts of those trying to convince Sri Lanka to comply with the resolution. It is more than likely that he received a nod and a wink from Washington before he undertook this journey.

Intriguingly, the Secretary-General apparently had given an assurance that he would have the resolution implemented. Is this another occasion that he has simply shot his mouth off without appreciating the gravity of what he was saying? His powers of implementation are only illusory. As the Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov once observed, when he was the Ambassador in New York and was requested not to smoke in the building on the orders of the SG, “The Secretary-General is no General. Just a Secretary”. Lavrov continued to smoke.

Compliance with the resolution, we are told, is the passport to enter the heaven of acceptance provided by the international community. (In reality, a small group of Western countries whose economic and military clout in the world may not be as significant as it used to be). In parallel, elements of the opposition continue to harp on the dangers of the UN Human Rights Council resolution, forcing the government to defend itself ever so vigorously and its efforts to comply with it.

Thus we have the ideal combination of circumstances, both external and internal, conducive to giving effect to the resolution. It is noted that many of the UN Human Rights Council country specific resolutions adopted by majority vote remain unimplemented. Many resolutions targeting the bad apples, as identified by the so-called “international community”, have been regularly adopted by the UNHRC and are just as routinely ignored. We have the usual club of usual suspects such as North Korea, Syria, Iran, and Belarus in this category. Israel gets targeted regularly by the majority of the membership of the Council while some members of the “international community”, the champions of human rights, abstain or vote against the resolutions on Israel.

The U.S. has even threatened to pull out of the whole process given the “unfair” treatment of Israel by the Council. Myanmar has escaped the basket of bad apples and, up until the eruption of the Rohingya crisis, asked to pay a relatively small price for its newly acquired status. The real question is whether much has changed in the behaviour of the bad apples as a consequence of the adoption of UNHCR resolutions and increasingly shrill cries of the human rights community. The answer has to be a resounding NO.

The extreme selectivity of UN Human Rights Council resolutions, and the avoidance of the rich and the powerful in its criticisms, has made these resolutions all but meaningless. The big powers studiously avoid criticising each other. Serious and repeated violations of internationally agreed human rights standards by certain countries tend to escape the attention of the Council. While others get targeted regularly. No country quakes in its boots at the prospect of a Council resolution being adopted against it. Countries prefer the UPR (Universal Periodic Review) process which actually helps to advance human rightds standards.

Many members of the HRC could not understand why Sri Lanka spent so much time, energy and resources fighting the adoption of resolutions in the past when the outcome seemed to be obvious and the willingness with which it cosponsored the resolution in 2015 with such objectionable provisions.

Many provisions of the 2015 resolution 30/1 have gone way beyond the mandate of the Council. For example it welcomes the government’s commitment to devolve political authority by taking necessary constitutional measures, affirms the importance of participation in a Sri Lankan judicial mechanism, including the special counsel’s office, of foreign judges, defence lawyers and authorized prosecutors and investigators, encourages the government to accelerate the return of land to civilians and end the involvement of the military in civilian activity, etc.

It could be argued that the Council, established with a mandate to advance the adherence to global human rights standards, not just standards favoured by a group of western countries, had no business calling on a sovereign state which had only recently emerged from a devastating terrorist challenge to its territorial integrity and sovereignty, to leave all else aside and proceed to reduce its security forces from a part of the country, return land acquired for security reasons or introduce constitutional amendments. And now there is pressure to do these things post haste, fuelling the goals of extremist elements.

Sri Lanka’s enthusiasm for cosponsoring the resolution of 2015 may not have gone down too well with its traditional supporters. The precedent it set could be unhelpful to many. It is doubtful if Sri Lanka did itself any substantive favours either. If Sri Lanka were to renege on the commitments, that it so readily undertook, it may be confronted with the wrath of the so called “international community” and it would not be surprising if the traditional supporters just turned the other way.

The enthusiasm with which Sri Lanka agreed to comply with prescriptions for reconciliation recommended by external entities will come to bite it sooner than later. As to whether these external entities, essentially the so called “international community”, took the trouble to take in to account the views of all elements of the Sri Lankan population or only the concerns of the pressure groups operating in their own countries is a valid question to ask.

Judging by the reactions of a significant and vocal part of the Sri Lankan population, it is doubtful that they took much pain to reflect the concerns of the majority of the people. Unfortunately, this could be a recipe for generating serious disenchantment and the releasing of uncontrollable forces as has happened in the past.

Have the High Commissioner and his advisers paused to consider the consequences of pushing for the implementation of the resolution knowing the widespread resentment that it has generated? Is his desire to see blood on the streets to achieve his goals? One recalls the situation resulting from the Indo-Lanka accord and the years of bloodshed that followed.

External prescriptions have hardly ever assisted a country to resolve its internal problems. Usually, a country’s problems are exacerbated by blind adherence to externally prescribed cures.

*The writer is a former Permanent Representative of Sri Lanka to the United Nations. The following are extracts from his presentation to the Organisation of Professional Associations, Colombo.