The TPP’s Impact On Vietnam: A Preliminary Assessment

By ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute

By Le Hong Hiep *

The conclusion of the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership (TPP) Agreement negotiations on 5 October 2015 has been hailed by the twelve participating countries as a landmark for regional economic integration. The agreement is also seen by many experts as having far-reaching regional and global strategic implications. As a member of the TPP, Vietnam will stand to benefit from the agreement both economically and strategically, but the country will also be faced with considerable challenges. How Vietnam will capitalize upon the opportunities and handle the challenges may shape the country’s economic, political and strategic trajectory for years to come.

This essay provides a preliminary assessment of the potential economic, political and strategic impact of the TPP on Vietnam. It argues that Vietnam may gain significantly in terms of GDP growth, export performance and FDI inflow. In the long term, the economy will also benefit if further legal, institutional and administrative reforms are undertaken along with improvements in the state-owned and private sectors. Politically, immediate impacts will be limited, but the country may become more open and conducive to further liberalization in the long run. In strategic terms, the agreement will help the country improve its strategic position, especially vis-à-vis China in the South China Sea, although such an impact is not imminent and should not be exaggerated.

The essay is divided into four sections. The first provides an overview of Vietnam’s recent international integration agenda and its participation in TPP negotiations. The other three will analyse the agreement’s economic, political and strategic impacts on the country.

VIETNAM’S PARTICIPATION IN TPP NEGOTIATIONS

Since the adoption of Doi Moi in the late 1980s, Vietnam has been consistently pursuing broader and deeper international economic integration to support its economic growth. Various official documents of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) have stressed the importance of international integration as a tool to develop the country.1 Most recently, in April 2013, the Central Committee of the CPV passed Resolution No. 22-NQ/TW on international integration, confirming that “proactive and active international integration is a major strategic orientation of the Party aimed to successfully implement the task of building and protecting the socialist Fatherland of Vietnam” (CPV, 2013). Such guidelines have resulted in Vietnam’s rather liberal foreign trade agenda over the past two decades.

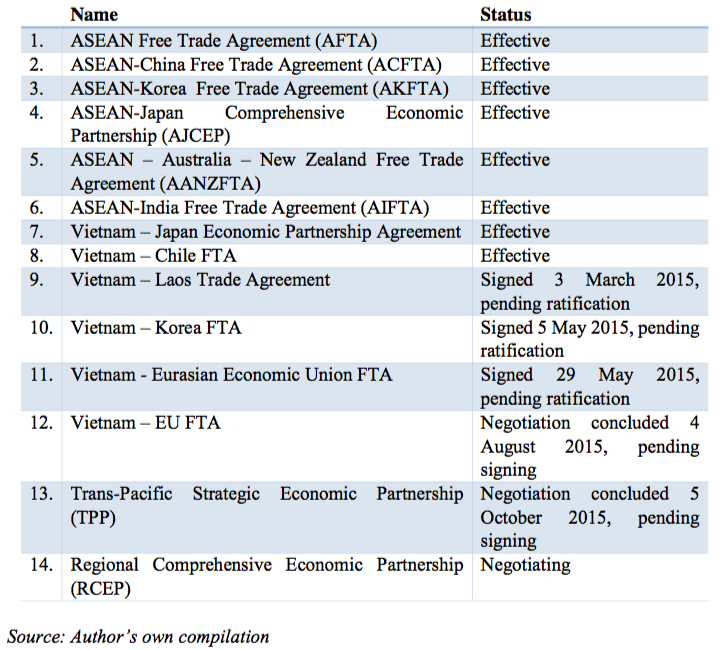

A major indication of this policy is Vietnam’s aggressive pursuit of both multilateral and bilateral free trade agreements (FTAs) with various partners, especially in recent years (see Table 1).

Among the FTAs that Vietnam is pursuing, the TPP is of particular importance for a number of reasons. First, as TPP member countries account for 39% of Vietnam’s total exports in 2014, deeper integration with these economies will enhance Vietnam’s export performance. As Vietnam has not concluded a bilateral FTA with the United States, the TPP will also be an alternative solution to boost Vietnam’s exports into this important market. 2 Such considerations were highly relevant after the 2007-08 Global Financial Crisis broke out and constrained Vietnam’s export performance, a major engine of the country’s growth.3 In addition, a greater inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI) may be another healthy impact of the TPP on the country’s long-term economic prospects.4

The high standards set by the TPP provided yet another important incentive for Vietnam to pursue the trade deal as certain segments within the country’s leadership expected to use the agreement to push for substantive domestic reforms (see for example Vinh, 2015), especially regarding state-owned enterprises (SOEs).5 Meanwhile, Vietnam’s policy makers also view the TPP as a measure to balance against China’s unwarranted economic influence. In 2014, for example, China accounted for 29.6% of Vietnam’s total imports, and Vietnam ran a deficit of US$28.96 billion in its trade with the northern neighbour (General Department of Customs, 2014). Such a heavy dependence on China for imports has been seen as a security vulnerability for the country. TPP’s strict regulations such as the “yarn forward” rules of origin6 are therefore expected to help Vietnam improve its trade position vis-à-vis China in the long run.

According to a document released by the Ministry of Industry and Trade (MOIT), during the negotiations, Vietnam held broad consultations with various stakeholders, including the Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry, industrial associations, representatives of socio- political organizations, researchers, and independent experts. The MOIT (2015, p. 5) also states that it has well achieved negotiating mandates by:

- Successfully safeguarding Vietnam’s “core interests”. It is expected (by the Ministry) that Vietnam will significantly expand its exports as well as GDP, and create more jobs after the agreement comes into effect;

- Ensuring that commitments made by Vietnam are consistent with the CPV’s international integration agenda, and rules and norms set by international organizations to which Vietnam has been a party; and

- Securing other TPP members’ agreement to accord Vietnam with a “considerable level of flexibility” in implementing TPP’s regulations.7 A number of TPP members have also pledged technical assistance to help Vietnam fully implement the agreement.

In sum, the economic and strategic importance of the TPP and Vietnam’s international economic integration strategy accounted for the country’s strong political will to pursue the pact despite its development gap with other members. The conclusion of TPP negotiations in October 2015 was well received in the country, with the mainstream media highlighting the economic opportunities that the agreement may bring Vietnam. At the same time, cautionary notes have also been raised by government agencies and experts regarding the challenges that Vietnam will have to overcome to capitalize upon those opportunities. The following section will assess these economic impacts on the country.

ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES

So far, most analyses tend to concur that Vietnam will benefit significantly from the TPP (see for example Bloomberg, 2015; Eurasia Group, 2015; Petri, Plummer, & Zhai, 2012; Voice of America, 2015; Wall Street Journal, 2015). According to some of these, Vietnam may even emerge as the “biggest winner” among TPP member countries (Bloomberg, 2015). For example, experts from the World Bank estimate that by 2030 the TPP would cumulatively add about 8% to Vietnam’s GDP (Voice of America, 2015). Meanwhile, research firm Eurasia Group claims that by 2025, Vietnam’s GDP will be 11%, or $36 billion, higher than without the trade pact (Eurasia Group, 2015, p. 8). Drawing on analyses by “independent experts”, the MOIT has also claimed that the TPP may help Vietnam expand its GDP by US$33.5 billion and its exports by US$68 billion within a decade (MOIT, 2015, pp. 9-10).

Since the final text of the agreement has not yet been disclosed, the following sub-sections will instead draw on a summary provided by the US Trade Representaive (2015) to provide a preliminary analysis of the impact of the agreement’s key chapters on Vietnam’s economy.

Trade in Goods and Services

An important implication of the TPP for Vietnam may be its deeper participation in the global/regional production network. The anticipated movement of investments by multinational corporations from non-TPP members into the country can help improve Vietnam’s position in the network by expanding its production base and facilitating the establishment of industrial clusters, especially in the industries in which Vietnam enjoys comparative advantages, such as textile and apparel. However, the impact may be constrained if Vietnam does not act fast enough to attract these investments before and in case the TPP is expanded to include other countries, especially its FDI competitors (e.g. Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, or even China).

By eliminating or reducing 18,000 tariff lines on industrial as well as agricultural products, the TPP will create both winners and losers in Vietnam. Greater access to major markets, especially the US and Japan, will boost the export of some major product categories in which Vietnam enjoys comparative advantages, such as textile and apparel, seafood, aquaculture, agriculture and forestry products. At the same time, the livestock industry will face extreme difficulties due to its low competitiveness. The industry, however, will have 10 years to enhance its competitiveness before having to compete with duty-free imported products. Producers of product categories such as dairy, soybean, corn and animal feed inputs may also expect to face considerable challenges (MOIT, 2015, p. 12).

Textile and apparel is generally considered the biggest winner due to its well-established position in the global supply chain and to Vietnam’s relatively low labour costs. Officials from the Viet Nam Textile and Apparel Association (VITAS) estimate that once the TPP comes into effect, the industry’s export turnover could double (Viet Nam News, 2015).8 As each additional billion of dollars in textile and apparel exports is expected to create 250,000 new jobs (MOIT, 2015, p. 10), the TPP will be an essential tool for Vietnam to solve the unemployment problem, thereby avoiding social instability. The footwear industry is likely to play the same role as it is also expected to benefit significantly from the TPP.

Both multinational and local firms will benefit from the expansion of Vietnam’s textile and apparel exports. However, since more international firms will invest in the industry to take advantage of the TPP, labour supply for the industry may start drying up at some point, causing labour costs to increase in coming years.9 The upward pressure on labour costs is further intensified by the government’s schedule to increase minimum wage periodically, and especially workers’ right to an independent union as prescribed by the TPP itself. Consequently, if Vietnamese firms in the industry, especially small and medium-sized enterprises (SME), cannot improve their technology and governance to enhance productivity, they may lose out to MNEs in the long run when low labour costs are no longer their competitive edge.

Where trade in services is concerned, the TPP includes core obligations such as national treatment and most-favoured nation treatment (US Trade Representative 2015). As these are core obligations that are found in the WTO and other trade agreements to which Vietnam is already a party, the rules are compatible with the country’s roadmap of cross-border service liberalization and do not pose new challenges. However, as the least developed country in the group, Vietnam needs to quickly improve the competitiveness of its service sector before it is required to fully comply with TPP regulations. A case in point is the banking industry. Since 2012, Vietnam has been implementing a banking reform to create a leaner and healthier banking system. So far, the country has reduced the number of domestic commercial banks from 42 to 34 through state-sponsored merger and acquisition (M&A) deals between stronger and weaker banks. By October 2015, the State Bank of Vietnam (SBV) had also nationalized three banks. However, the banking system is far from stable and strong as governance remains an issue, especially among those currently or formerly state-owned. Moreover, the considerable amount of remaining bad debts continues to threaten the resilience and sustainability of the system and hinders the substantive preparation it needs to make in order to take on foreign competition.10

Investment

The TPP also requires members to adopt non-discriminatory investment policies and protections, while giving member governments the leeway to achieve legitimate public policy objectives. As Vietnam has been reliant on FDI as a pillar of its growth strategy, its government has made a lot of effort in recent years to improve the investment environment, from upgrading infrastructure to trimming red tape and improving the legal framework. A major indication is the 2014 Law on Investment, which simplifies the investment process, reduces uncertainties, and puts foreign investors on a more equal footing with domestic ones.11 Given these efforts made by the Vietnamese authorities and the TPP’s potential to expand Vietnam’s exports, it is likely that the trade pact will generate a large FDI inflow into the country once it comes into force.

State-owned Enterprises (SOEs)

SOEs play an important role in Vietnam’s economy. In 2013, for example, although representing only 0.9% of the total number of enterprises and employing 13.5% of the total work force, SOEs accounted for 32.2% of Vietnam’s GDP and 40.4% of the country’s total annual investment (GSO, 2015, pp. 62, 75-78, 103).

In essence, the TPP stipulates that member countries’ SOEs or designated monopolies will have to operate on market principles, except when doing so would be inconsistent with their mandate to provide public services. The SOEs will not be allowed to discriminate against the enterprises, investments, goods, and services of other member states. Under the agreement, member states are also required to make SOE operations transparent by providing relevant information, such as the state’s share in the ownership structure and these companies’ audited financial reports. Neither are member states allowed to provide subsidies or non-commercial assistance to SOEs which may have adverse effects on other member states’ businesses.

In this regard, Vietnam has submitted its reservations on defence and national security-related SOEs. For commercial SOEs, Vietnam has committed to exposing them to full and equal competition from private and foreign enterprises. However, Vietnam can still provide certain assistance to SOEs, though not to the extent that this may generate a negative impact on other member states’ companies.

The TPP therefore provides a significant impetus for Vietnam to accelerate its SOE reform, especially the equitization of these enterprises. Although SOE reform has been one of the three key pillars of Vietnam’s economic restructuring since 2012, its progress has been slower than expected due to unfavourable market conditions as well as resistance from certain SOE managers.12 Recently, however, the government has stepped up this effort and taken various measures such as opening up certain sectors traditionally monopolized by SOEs (e.g. coal, electricity and petrol distribution) to competition; expanding foreign investors’ ownership room in equitized enterprises; and disciplining managers failing to meet their equitization deadlines. These developments show that the Vietnamese government is aligning its SOE policy to TPP commitments, which may help improve the performance of SOEs as well as the whole economy in the long run.

Intellectual property and environment protection

The TPP seeks to set high standards on intellectually property (IP) protection, including the introduction of criminal procedures and penalties for commercial-scale infringements of intellectually property, which are seen as stricter than regulations under the WTO. The enforcement of such regulations will add costs to Vietnam’s businesses, especially SMEs, where the use of pirated software is still prevalent.13 In the long run, however, better protection of intellectual property is expected to provide stronger incentives for businesses to invest in creative industries that Vietnam is seeking to develop.

Another major concern regarding TPP regulations on IP is whether they will put constraints on Vietnam’s public health programmes such as its campaign against HIV/AIDS, due to the expected rising cost of medicines or the more restricted access to them. According to the MOIT, however, while Vietnam commits itself to the TPP’s common standards, it will have a “roadmap” of implementation commensurate with its “development level and enforcement capacity” (MOIT, 2015, p. 8). This implies that Vietnam may enjoy some flexibility in this regard, including assistance from other TPP members.

In terms of environment protection, the TPP may have some implications for certain businesses in the fishing and logging/furniture sectors. Some illegal and unsustainable fishing practices popular with small private fishing fleets will have to be repressed, while furniture companies will be advised to turn away from illegitimate yet cheaper sources of timber and related materials. The implications are uncertain, however, as they are subject to the enforceability of regulations in the Vietnamese context where violations are known to still take place and go unpunished despite an abundance of laws and regulations.

POLITICAL IMPLICATIONS

As Vietnam pursues more liberal economic reforms, optimists will have reasons to cherish the hope that one day, economic liberalization will lead to political democratization. However, this seems to be a distant scenario given the long time that it takes for democratizing effects to build up as well as the CPV’s effective strategies to maintain its grip on power while the country went through economic liberalization over the past thirty years.

A relevant cause for optimism about the TPP’s political effect on Vietnam is perhaps the CPV’s willingness to comply with the TPP’s labour regulations. Specifically, the TPP stipulates that member countries will have to protect fundamental labour rights, especially workers’ right to independent union and collective bargaining. Historical precedents, such as the Solidarity movement in Poland, show that independent labour unions can develop into influential political forces that bring about major changes. Such does not seem to be the case in Vietnam. There are several reasons for this.

First, the TPP’s labour regulations are actually drawn from the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) 1998 Declaration. As Vietnam has been a member of the ILO, its agreement to abide by the TPP’s labour regulations is just a re-affirmation of old commitments and is not tantamount to a new concession by the CPV towards political liberalization. Second, although the right to an independent union may be used by some to mobilize political changes in the long run, the CPV will most likely ensure that any labour union established will only serve economic purposes, i.e. to protect workers’ rights and economic welfare. In this connection, the Party and its security apparatus will probably construct certain tactics to “legally” constrain independent unions within certain boundaries, and to prevent them from being exploited politically.

In other words, rather than indicating a genuine relaxation of the CPV’s political control, Vietnam’s commitment to protect labour rights under the TPP is a rational choice made by the Party for other purposes. Proclaiming itself as “the vanguard of the working class”, the CPV has little reason to oppose the TPP’s labour regulations which are supposed to protect workers’ rights and welfare in the first place. Accepting these regulations will therefore contribute to the Party’s political legitimacy while giving Vietnamese negotiators ground to bargain for concessions in other areas.

That said, the TPP is likely to affect Vietnam’s political trajectory in the long run if certain conditions are met. First, it is essential that the implementation of the TPP helps accelerate the economic development of Vietnam and further expand its middle class, thereby laying the foundations for a democratic transition. Second, under competition pressures from the TPP, the CPV itself may find it necessary to undertake meaningful political reforms to free up the country’s economic potential from political and institutional constraints rooted in its one-party system. For example, at the 12th CPV Congress early next year, it is likely that the TPP will be featured as an opportunity for Vietnam, and serve as a basis for reformists to call for further economic as well as political reforms to help the country capitalize on the agreement. Finally, the TPP’s political implications will only become visible if there are mechanisms to ensure its full and effective implementation, especially regarding labour regulations. At the same time, Vietnam’s civil society also needs to develop along the way to take advantage of the narrow opening brought about by the agreement to push for broader political reforms.

FOREIGN POLICY AND STRATEGIC IMPLICATIONS

The TPP is indeed the first multilateral trade arrangement outside ASEAN that Vietnam has joined as a founding member and in which it has participated in the rule-making process. The TPP will therefore serve as another landmark in Vietnam’s international integration process. By embedding Vietnam more deeply into the regional trade and production network, the agreement will also help establish the country as an important economic and strategic partner for regional countries. Gradually, Vietnam’s own security and prosperity will become a matter of regional concern. In that sense, if the TPP can help expand Vietnam’s external trade and attract more foreign investment, it may well become a strategic tool for the country to promote not only its own prosperity but also its national security.

It is also noteworthy that the TPP is an American-led initiative. As such, Vietnam’s participation in the TPP will further strengthen its ties with the US. This is particularly important given Vietnam’s recent efforts to forge a closer relationship with the US as well as other regional powers, including Japan (another TPP member), to balance against China in the South China Sea.14 As evidenced by the recent surge in foreign investment into the country’s textile material industry, the TPP will also help reduce Vietnam’s dependence on China for material imports. As such, if the TPP comes into effect, although China may remain Vietnam’s top economic partner for the foreseeable future, its relative importance to Vietnam will be reduced due to the deepening of economic ties between Ha Noi and Washington. China’s economic influence over Vietnam will accordingly be curtailed, providing Vietnam with a better strategic position vis-à-vis its northern neighbour.

CONCLUSION

The TPP is an important landmark in Vietnam’s international economic integration process. Vietnam’s participation in the agreement was driven by multiple economic, political and strategic considerations. In economic terms, the agreement is expected to help the country achieve faster GDP growth, expand its exports, and attract more foreign investment. However, as the least developed member of the TPP, Vietnam needs to address challenges to improve its competitiveness and to maximize its potential gains from the agreement.

Politically, the agreement may mobilize support for more economic as well as political and institutional reforms. Contrary to the popular expectation that the CPV’s commitment to TPP’s regulations on labour rights may indicate a relaxation of the Party’s grip on power, the agreement is unlikely to lead to any significant political liberalization. This is because the Party and its security apparatus may come up with tactics to “legally” constrain the development of independent unions and to prevent them from being exploited for political purposes.

Strategically, the TPP reaffirms international economic integration as a key pillar in Vietnam’s foreign and strategic policy. The agreement will also help Vietnam further strengthen its ties with the US and become less economically dependent on China. However, the TPP’s effect in shifting Vietnam’s strategic balance between the two great powers will not be immediate. It may take years for the TPP to help Vietnam become less economically dependent on China, and for Vietnam and the US to build on the trust premium provided by the agreement. For the time being, the agreement will serve as a facilitator rather than a driver of Vietnam-US relations, and bilateral ties, at least in the short run, will still mainly be driven by Vietnam’s perception of the China threat in the South China Sea.

In sum, the TPP is likely to generate some positive impact on Vietnam, but this should not be exaggerated, and opportunities should be evaluated alongside challenges. The key test for Vietnam is whether the country can undertake timely and effective domestic reforms, both economically and politically, to meet the challenges and to capitalize on opportunities offered by the agreement. Be that as it may, the TPP should remain a case of “cautious optimism” for the country.

About the author:

*Le Hong Hiep is Visiting Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore. He is currently on research leave from his lectureship at the Faculty of International Relations, Vietnam National University – Ho Chi Minh City. The author would like to thank Cassey Lee and Daljit Singh for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Source:

This article was published by ISEAS as ISEAS Perspective 63 (PDF).

Notes:

1 For example, the CPV’s 9th National Congress in 2001 set out the guideline on “Proactive international economic integration”. In November 2001, the CPV Politburo issued Resolution No. 07-NQ/TW on “International economic integration”. At its 10th National Congress in 2006, the CPV reaffirmed the policy of “proactive, active international economic integration together with the expansion of international cooperation in other fields”. On 5 February 2007, the Party’s Central Committee passed Resolution No. 08-NQ/TW on “Some major guidelines and policies for fast, sustainable economic development following Viet Nam’s accession to the World Trade Organization”.

2 The US is currently Vietnam’s largest export market, accounting for 19 per cent of its total exports in 2014.

3 For example, Vietnam’s annual export turnover fell 9.7 per cent from US$62.7 billion in 2008 to US$57.1 billion in 2009 (GSO, 2012, p. 492).

4 By the end of 2014, the total registered FDI stock in Vietnam reached US$290.6 billion, of which US$124.2 billion has been implemented. The top ten investors in terms of registered capital were South Korea (37.7 bil.), Japan (37.3 bil.), Singapore (32.9 bil), Taiwan (28.5 bil), British Virgin Islands (18 bil.), Hong Kong (15.6 bil.), USA (11 bil.), Malaysia (10.8 bil.), China (7.98 bil.), and Thailand (6.75 bil.) (GSO, 2015, pp. 109, 113).

5 In 2014, China accounted for 29.6 per cent of Vietnam’s total imports, and Vietnam ran a trade deficit of US$28.96 billion vis-à-vis China (General Department of Customs, 2014). Heavy dependence on imports from China has been seen by many Vietnamese policy makers and politicians as a security vulnerability for the country.

6 The rules require Vietnam to use a TPP member-produced yarn in textiles in order to receive duty-free access to TPP member markets. As China is not a TPP member, while Vietnam depends heavily on China for yarn and textile materials, the TPP has prompted a surge of foreign investment in Vietnam’s textile industry. In the long run, such developments may help reduce Vietnam’s imports of textile inputs from China.

7 The document stresses that Vietnam was actually given “the most flexibility” in implementing TPP commitments, possibly because Vietnam is the least developed country among TPP members.

8 Vietnam’s textile and garment export turnover is forecast to reach US$27.5 to US$28 billion in 2015 (Viet Nam News, 2015).

9 There have been reports on international firms’ difficulties in setting up their factories in the country due to labour shortage. See, for example, Dow Jones Business News (2015).

10 By May 2015, the bad debt ratio announced by the SBV was 3.15 per cent, down from 17.2 per cent in 2012, although some reports indicate the actual ratio might still be higher. The reduction mainly resulted from the transfer of bad debts from commercial banks to the state-owned Vietnam Asset Management Company (VAMC).

11 For example, according to the new law, a business organization with foreign capital shall be treated as a “domestic investor” if its foreign investor(s) holds less than 51% of its charter capital. In this case, the foreign investor(s) shall not be required to obtain an Investment Registration Certificate. Previous regulations require foreign investors to apply for the certificate even when they invest only 1% of a local firm’s charter capital.

12 In 2011, the government set the target of equitizing 531 SOEs by the end of 2015, but by November 2014, this had happened to only 214 SOEs (Ministry of Finance, 2015).

13 For example, according to a senior Microsoft official, 85 per cent of its softwares used in Vietnam are pirated copies. More details available at: https://www.microsoft.com/vietnam/news/genuineshop_090425.aspx. Vietnam is also on the “watch list” for intellectual property rights protection and enforcement, prepared by the Office of the US Trade Representative. More information is available at: https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/2015- Special-301-Report-FINAL.pdf

14 For an analysis of recent dynamics in Vietnam’s relations with the US and China, see Hiep (2015).

References

Bloomberg. (2015, 9 Oct). The Biggest Winner From TPP Trade Deal May Be Vietnam Retrieved 20 Oct, 2015, from http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-10- 08/more-shoes-and-shrimp-less-china-reliance-for-vietnam-in-tpp

CPV. (2013). Resolution No. 22/NQ-TW Retrieved 16 Oct, 2015, from http://www.mofahcm.gov.vn/vi/mofa/nr091019080134/nr091019083649/ns140805203450/NQ22.ENG.doc/download

Dow Jones Business News. (2015, 18 Oct). Why the TPP Trade Deal Isn’t All Good for Vietnam’s Factories Retrieved 20 Oct, 2015, from http://www.nasdaq.com/article/why-the-tpp-trade-deal-isnt-all-good-for-vietnams- factories-20151018-00074

Eurasia Group. (2015). The Trans-Pacific Partnership: Sizing up the Stakes – A Political Update. New York: Eurasia Group.

General Department of Customs. (2014). Customs Trade Statistics. Retrieved 27 Jun 2014 http://www.customs.gov.vn/Lists/EnglishStatistics/ScheduledData.aspx?Group=Trade%20analysis&language=en-US

GSO. (2012). Statistical Yearbook of Vietnam 2011. Ha Noi: Statistical Publishing House. GSO. (2015). Statistical Handbook of Vietnam 2014. Ha Noi: Statistical Publishing House. Hiep, L. H. (2015). The Vietnam-US-China Triangle: New Dynamics and Implications. ISEAS Perspective, 45.

Ministry of Finance. (2015, 19 Jan). Nam 2015 tap trung tai co cau doanh nghiep Nha nuoc (Government to focus on restructuring SOEs in 2015) Retrieved 9 Mar, 2015, from http://www.mof.gov.vn/portal/page/portal/mof_vn/1539781?pers_id=2177014&item_id=158447520&p_details=1

MOIT. (2015). Hiệp định Đối tác Xuyên Thái Bình Dương (Hiệp định TPP) và sự tham gia của Việt Nam [The TPP and Vietnam’s participation]. Ha Noi.

Petri, P. A., Plummer, M. G., & Zhai, F. (2012). The Trans-Pacific Partnership and Asia- Pacific Integration: A Quantitative Assessment (Vol. 98). Washington D.C.: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

US Trade Representative (2015). Summary of the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement Retrieved 20 Oct, 2015, from https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press- office/press-releases/2015/october/summary-trans-pacific-partnership

Viet Nam News. (2015, 22 Jul). Textile and garment exports to TPP market up 70 per cent Retrieved 20 Oct, 2015, from http://vietnamnews.vn/economy/273384/textile-and- garment-exports-to-tpp-market-up-70-per-cent.html

Vinh, P. Q. (2015, 4 Oct). Đại sứ Việt Nam tại Mỹ: TPP là kỳ tích lịch sử [Vietnam’s Abassador to the US: TPP is a historic feat] Zing News Retrieved 19 Oct, 2015, from http://news.zing.vn/Dai-su-Viet-Nam-tai-My-TPP-la-ky-tich-lich-su-post586359.html

Voice of America. (2015, 13 Oct). World Bank Sees Vietnam As ‘Winner’ from TPP Retrieved 20 Oct, 2015, from http://www.voanews.com/content/world-bank-sees-vietnam-as- winner-from-tpp/3004217.html

Wall Street Journal. (2015, 18 Oct). Why You May Soon See More Goods Labeled ‘Made in Vietnam’ Retrieved 20 Oct, 2015, from http://www.wsj.com/articles/why-you-may- soon-see-more-goods-labeled-made-in-vietnam-1445211849

a good essay, well documented and structured.

But, probably due to its limited length and scope,it misses the longer perspectives for instance the possible rising of Vietnam as a sea power thanks to its trade with privileged Pacific rim partners and to its long coast line dotted, from the 1st till the 17th century, with many active sea faring thalassocraties such as Óc Eo and the Champa comptoirs along its central and southern littoral .